annual Illuxcon in Allentown Pennsylvania.

It is an amazing show in a great museum with a wonderful permanent

collection; all this diversity in amazing art at once can be overwhelming but

at the same time energizing to the artist, both amateur and professional alike.

convention includes students showing their portfolios to all the professionals

here in hopes of making connections, getting feedback and possibly getting

work. This post is a response to a commonly

repeated question I have heard at least a dozen times already from students

showing their portfolios to the professionals here. The question that keeps coming up is “how do

you paint flesh tones?” This is not a new question exclusive to this show;

I hear it all the time with students or would be artists everywhere.

important it is for any artist to start their training traditionally. I might sound like some old art codger here

grumpily chewing on the fat of another generation shift in the arts, but I am

not. Mixing colors traditionally from

physical paint helps solve so many problems with where color comes from and how

to control color tones and color shifts from those mixtures. If you just buy the tubes of paint just to

practice mixing them without painting anything I would still recommend doing

so. It is time well spent and the

knowledge you will gain from the physical act of mixing is invaluable to say

the least.

to help illustrate some of the concepts.

Here are a few things to consider:

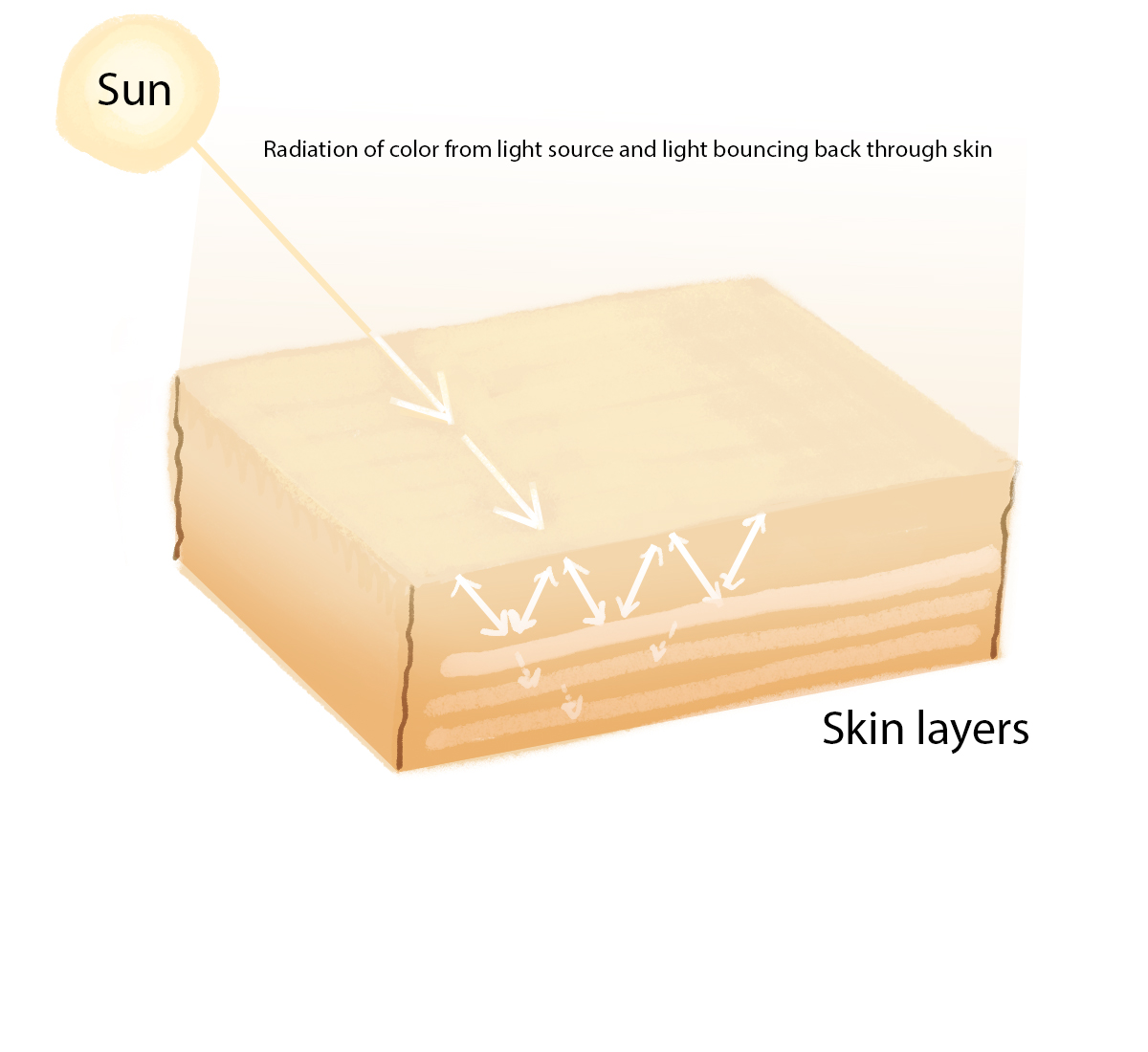

illuminates it to a certain extent depending upon the power of the light

source. As an example, a part of what we

see when we look at a model under a spot light is surface illumination and the

other is the slightly internally lit flesh depending upon the powerfulness of

the light source.

in this case we are concerned with the local color of flesh. Flesh has a range of hues from yellowish to

very dark, almost blue – purple in hue.

But no flesh is identifiably a straight hue, red, orange, green,

etc. They are all muddy versions of the

root hues.

an additional hue to the surface colors distorting them towards a temperature

bias complementing the light source, warmer lights a warmer mixture, cooler

lights a cooler mixture.

light that fills the spaces that the direct spotlight does not influence. If

the sun is the primary light source then the sky is the indirect light

source. In most universities and

ateliers, the spotlight is the direct light source while the fluorescent

overheads and the light coming through the windows from the sky are the

indirect light source(s). In contrast,

north light studios are primarily lit directly from the sky (cool temperature)

and the indirect light source is warm.

object will be directly lit. In addition

to the shadow side there are the turning surfaces between the direct light

source and the shadows. These planes that are not perpendicular to the

light are called oblique planes. The

direct light hitting these surfaces drops off in its directness as the surfaces

turn away from the primary light source and start taking on the influence of

the indirect light source.

indirect light source will be the temperature opposite.

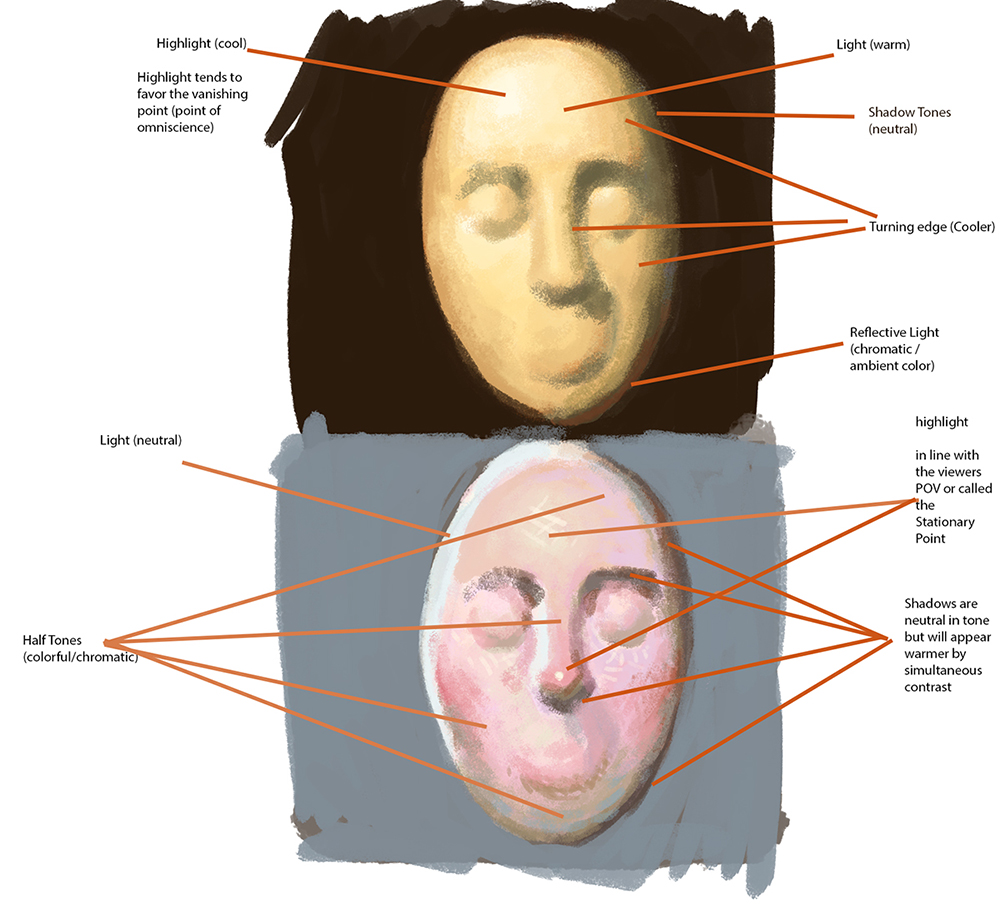

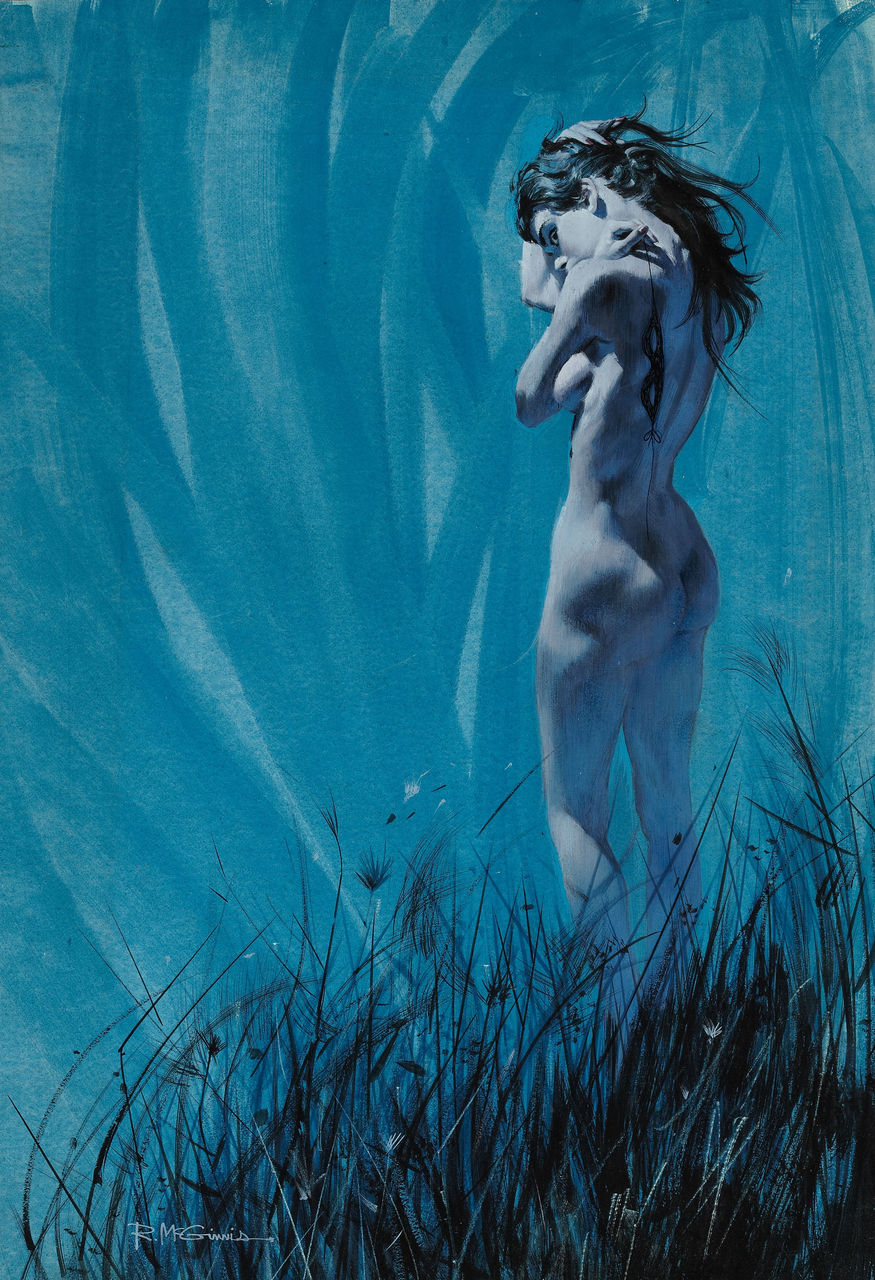

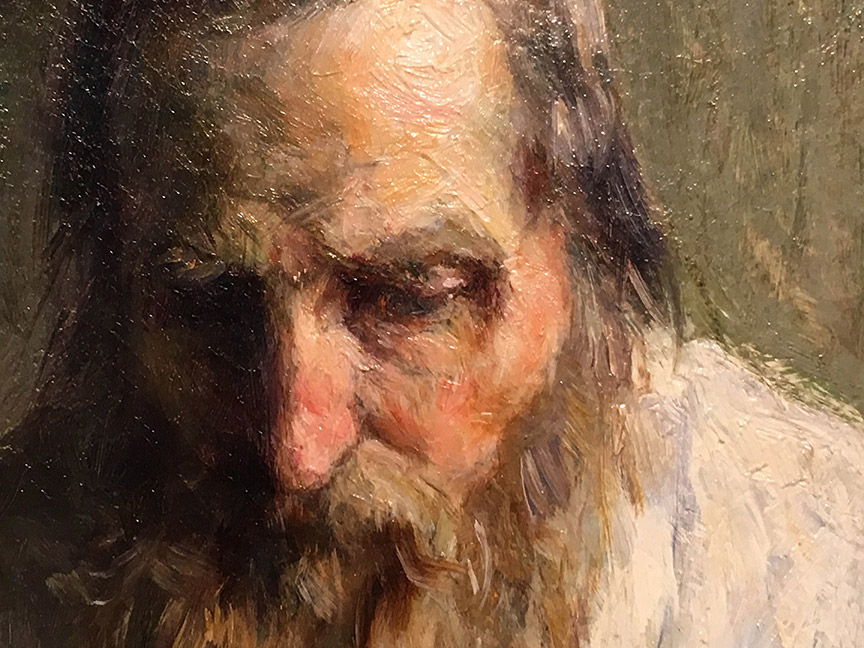

old masters and I have two of those examples here, classical and romantic

lighting. Classical lighting was the

typical approach to lighting a painting until around the mid 1800’s. Classical lighting was based upon a single

powerful light source. Caravaggio is a

perfect example of this lighting scheme.

This type of painting required layers upon layers of scumbling and

glazing colors to achieve the brilliant light and the magnificent lifelike quality

of rendering. The palette of colors

available at this time were not as vibrant as we have now so to keep the hues

colorful they needed to be applied in their pure state (glazing), unadulterated

by mixtures with other hues. Most of the

flesh tones were not so colorful as they were tonally correct to how flesh

looks and feels. Color was most

chromatic within the reflected lights in the shadows tones, drapery, etc.

invented and at this time the kind of painting also shifted away from the high

contrast lighting to a flatter less harsh look called romantic lighting. This lighting scheme allowed for the hues to

exist to a greater extent throughout the surfaces of the flesh tones. In addition the light planes and the shadow

planes were neutralized and reduced in contrast. Delacroix has been claimed to have started this shift in color/lighting but I think Bouguereau took the technique and just ran with it.

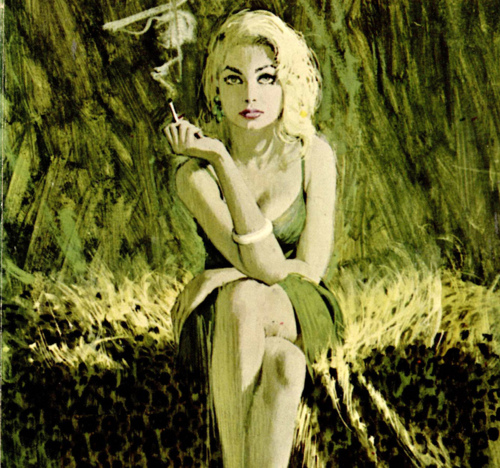

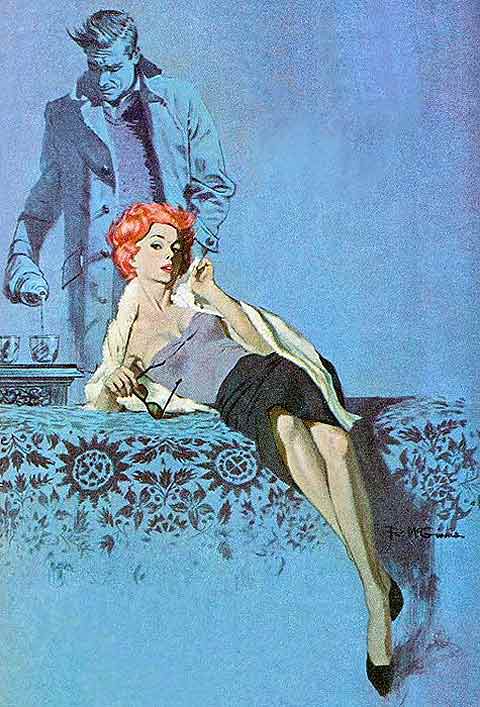

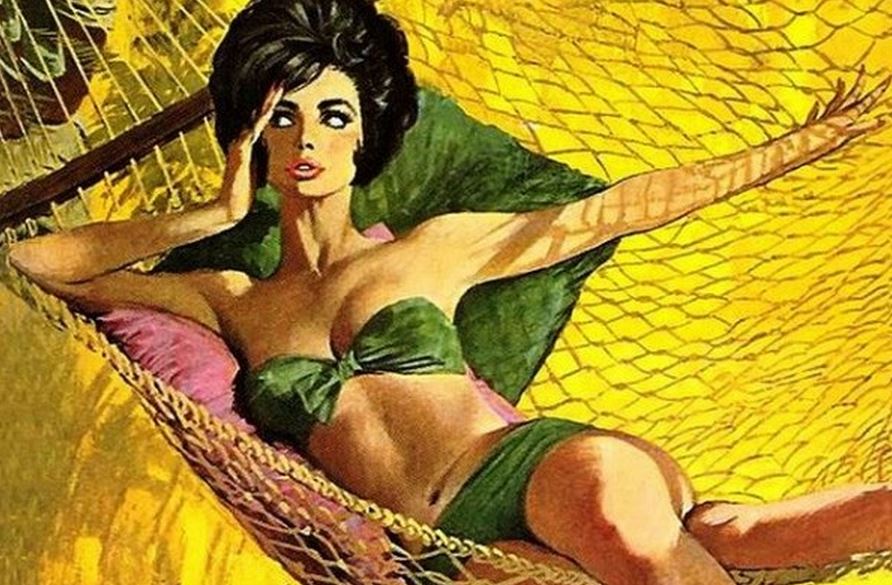

with illustration. I refer to this

period of color as the color recipe era.

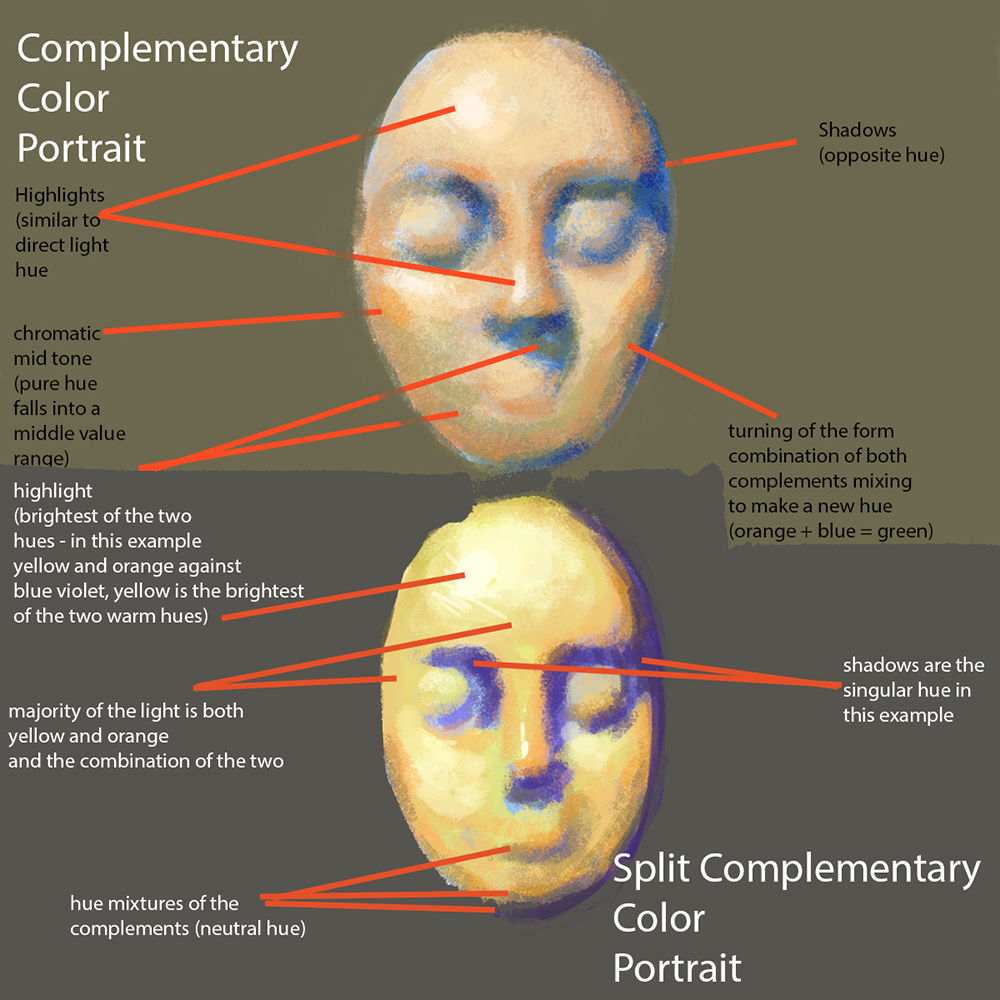

Illustrators were competing to have their magazine covers seen, pulp

novels were huge and the only way to get a product to stand out was to engineer

a crafty color scheme that would feel unique against the rest of the covers. During this time the color wheel was invented

as a tool for concocting these recipes (Munsell’s color sphere and color

wheel). Monochromatic, analogous, complementary, split complementary, triadic, quadratic,

and tetradic schemes were invented and color has never been the same

since.

paint flesh color” the first objective in your own art is to determine how you

are going to use light to tell your story. Are you going to use normal lighting or

staged lighting, or are you going to use the color wheel and find a range of

colors as a recipe to paint your picture?

This will determine how realistic you will need to depict the flesh in

your piece. The more realistic the piece

the more work that goes into making every surface change feel correct.

with. If you are working digitally this

is almost more important because there is no basic palette to begin the

painting, the programs you use have every available option ever conceived and

if you do not understand color theory then there is no starting point to cull

down the colors required to make an image work.

As you first learn to paint flesh a really good basic palette would be

the primary palette, consisting or red, yellow, blue, along with black and

white as shade and tinting tools respectively.

To give more options to the range of flesh tones in the lights and

shadows create the primary palette with a warm and cool version of each hue to

work with. Having the options of

different temperatures per each hue gives you a greater chance of making

convincing light and shade tones.

will explain in the next article. I will

show how to set up the palette and a way of mixing colors for direct painting

that I learned from my mentor Sebastian Capella and later from my years

studying the Reilly method.

0

0

1

1234

7037

my art room

58

16

8255

14.0

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:10.0pt;

font-family:Cambria;}

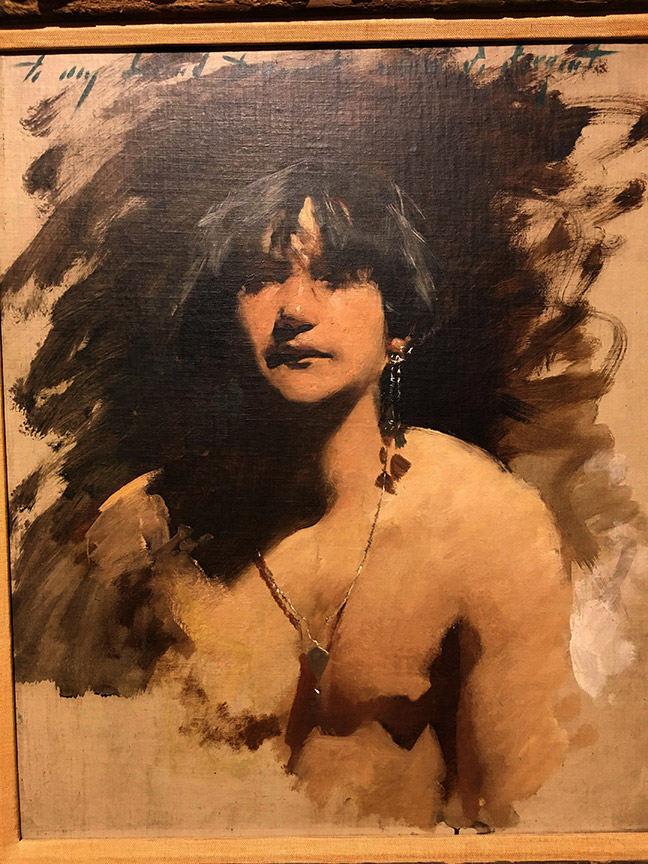

local museum or in a museum wherever you travel. It is so important to study what has come

before you; all the answers are there in every canvas including how the paint

is applied and in what order it is applied to the surface. This detective work will help you understand

how to create your own canvases. For now

I leave you with a few amazing examples of some fantastic paintings with

unbelievable flesh tones from the permanent collection here in the Pennsylvania

Art Museum. I learned a ton looking at

these canvases and helped me to better understand how the old masters used to

layer color to achieve the look and feel of their work. But that’s for another article.

A great post. I have ony seen discussions of a portrait/flesh palette in terms of the classical and romantic palettes. The others you brought up were a revelation. I'd seen them before in paintings, but not appreciated what they actually were doing. Thank you so much. I look forward to the next posts in this series.

thank you.

Awesome, Ron. Really covers a lot, and well.

I really notice the similarities in that particular John Sargent painting, and Jeff Jones' work. Wonderful.

I really notice the similarities in that particular John Sargent painting, and Jeff Jones' work. Wonderful.