Welcome to the return of Sunday Skills, the weekly (ish, deadlines allowing) article about the little ideas in art that can have a big impact. As always, feel free to ask questions liberally on Sunday, because I will answer everything I can on Monday. After that…who knows 😉

When I started my career in covers in late 2014 I could barely draw. And I’m not being modest. I had to spend a lot of time on meticulously-constructed reference photography to get by.

CRUTCHES

There seems to be a pervasive belief among artists trying to break into their chosen fields, that there are certain things they “should” be able to do. “I should be able to draw a human without this much reference! I should know how color works; why am I such a donkey?!”

The fact of the matter is, you can’t and/or don’t. So what are you going to do about it? Dodging the issue and beating yourself up is the common solution, but it’s also the only one guaranteed to get you nowhere and make you feel bad. Maybe you just can’t draw that figure from your head, or nail those colors from memory…yet. That is completely OK because we all – pros, amateurs, enthusiasts – have certain things we are currently just no good at. The great news is that we can still make art! If no one was allowed to make art until their skills were totally perfect it would be an artless world, and a worse one.

As an analogy, let’s examine crutches. When you see someone walking on crutches you don’t walk up to them and ask “What the hell’s the matter with you? Why don’t you just buck up and walk on your own two legs with the power of will alone?” No, you certainly don’t do that. You understand that they’re injured, and are probably doing everything and anything that they can to regain the ability to walk on their own. You probably admire that they’ve even shown up here in the world at all, and maybe you have some empathy for them. Having been on crutches myself for a long time when I blew out my ACL I can tell you: people on crutches have a pretty easy time making friends and getting help – so there’s actually a lot of potential in that humility.

If you’re not going to walk up and berate the person on crutches, why do artists do that to themselves? It’s because we think of walking as such a natural human ability that when someone doesn’t possess it, we know something has gone wrong. We don’t blame them. But we blame ourselves for lacking artistic abilities because we “should have them already, as a component of the talent package I received at birth.”

Yeah; no.

Once upon a time everyone did have to learn to walk. Walking is only natural as long as we’ve learned how to do it, and practiced it. And artistic skills are just the same! There are a lot of people out there who can do the things you’re trying to do, and if you ask them how (which I do a lot as part of the podcast), they NEVER say “oh I’m just talented at this; it was easy.” No, they can tell you exactly what types of things they did to improve, and in how much volume, and for how long. Every artist testimonial I’ve come across and every scrap of scientific literature I’ve read suggests that Every. Single. Artistic. Ability. can be developed in time, by anyone. You can learn these abilities, I promise you.

But you probably also want to make art now. You feel like you need to start walking! I agree. So, you have to use crutches. In art, a crutch can be any sort of tool or technique that lets you do things you couldn’t otherwise do; it lets you raise your game to where it needs to be to start getting hired. Here are a few examples:

- Using reference photography to bash pictures together and generate ideas because you can’t sketch or draw what you have in your head well enough to explain it to anyone, or explore it for yourself.

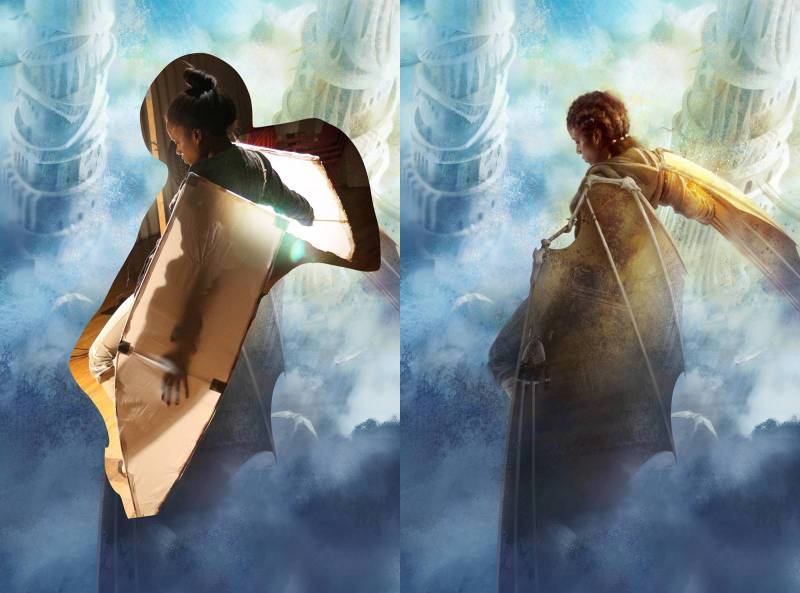

- Using tight photographic reference to execute your designs or draw your figures, because you lack drawing ability (see the side-by-side above).

- Building/crafting low-quality stand-ins for items you can’t afford or even find for reference shoots. Take a look at the “wings” in the picture above – those took me like 6 hours to build, but I had to do it because I didn’t trust myself to come up with all the information they’d generate in less time than that.

- Using color palettes borrowed from expert photographers (even if you don’t understand them) to achieve better color.

- Tracing because you can’t improve on the reference with your current drawing ability.

- Using in-program perspective grid tools to map out an environment because you can’t envision it, or don’t know perspective well enough to build it.

- Using 3D assets in illustrations to save time, or because you can’t draw.

- Lighting 3D assets in the computer and defaulting to those answers because you don’t fully understand light.

- Getting a teacher or coach to paint over your work and give you suggestions of how to improve the piece before turning your work in to a client, not after.

Wow, there’s a lot of “can’t” and “don’t” and “feel dumb when I have to say it out loud” on this list, but honestly I’ve used almost every one of these techniques at one time or another. It’s naturally embarrassing; we all want people to think well of us: to praise us and consider us smart and good at what we do. But (and this is SUPER important) WE’RE NOT HIRED FOR OUR SKILLS. We are hired for our art. It’s our job to make someone pick up a book, or say “Cool!” when they’re opening their next pack of Magic cards – that’s the job.

Besides, crutches have a way of teaching you more than you might expect. I’ve learned a lot about how fabric folds and moves by tracing fabric for hours and hours. It gets into your blood. One of the biggest open secrets amongst pro artists is that almost all of them have developed certain crutches into high-level abilities. How? By taking away the iniquity the crutch is meant to support. Imagine how good your paintings might look if you used tight photo-reference AND you could already draw! That is what I’m talking about, and there’s a lot more specific examples I hope to get into in a later article.

But for now, it’s OK to limp along. As long as you’re walking! I’d like to leave you with this challenge: if you have a big gap in your ability, find or invent a crutch to cover it up by the end of this week. Start working with the crutch, and seeing what it can teach you, and how it can help you. Feel no shame. Before you know it, you’ll be sprinting away.

What a great away to put it! These are the things we did in art school that our teachers never talked about, except to tell us to move away from exact photo-reference-copying, which always made us feel like we were cheating.

I needed to hear this right now. Thank you!

Well said, Tommy. You don’t get any extra points for being able to walk without crutches. The internet can be so demoralizing in making people think they “should” be able to do this or that, especially when they can’t see the crutches the other folks are probably using.

Thanks for posting this; it was really inspiring