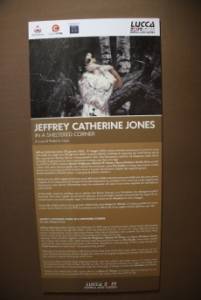

Last November the Lucca Comics and Games Festival in Lucca, Italy hosted an exhibit devoted to the art of Jeffrey Catherine Jones; the show consisted of 25 oil paintings and 34 works on paper, all from the extensive collection of one of Jeff’s closest friends, Robert K. Wiener. The Festival also held a screening of Maria Paz Cabardo’s award-winning documentary, Better Things: The Life and Choices of Jeffrey Catherine Jones (which I’ve written a little bit about in the past on Muddy Colors).

The show’s organizer, Roberto Irace, produced a book to commemorate the exhibition and asked Robert and George Pratt to write a little about Jeffrey; I was honored to write the introduction. Since it was published in Italian and only available to attendees to Lucca, I thought it would be nice to share the essays (with Robert’s and George’s permissions) with all of Jeffrey’s fans.

Photos of the show are courtesy of Robert K. Wiener.

_______________________________________

Introduction by Arnie Fenner

We live in a time when there is an attempt to define and somehow categorize everything and everyone—and that simply doesn’t work when writing about Jeffrey Jones. Enigmatic. Contradictory. Conflicted. Sadly troubled. Definitely brilliant: yes, it’s fair to describe Jeff—and, later, Jeffrey Catherine Jones—in all of those ways and more. But I think he (and eventually, she) defies easy explanations: Jeff was complicated and can’t be reduced to a simple stereotype. (If he could…we wouldn’t be talking about him.) I also believe that Jeff “being difficult”—to work with, to live with, to understand entirely—as he once ruefully described himself, was a reflection on his melancholic struggles with alcohol, his personal life, his mental health, and career. All of which, conversely, resulted in joyful and affecting art that is beloved and celebrated around the world.

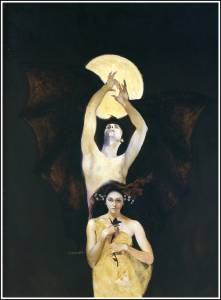

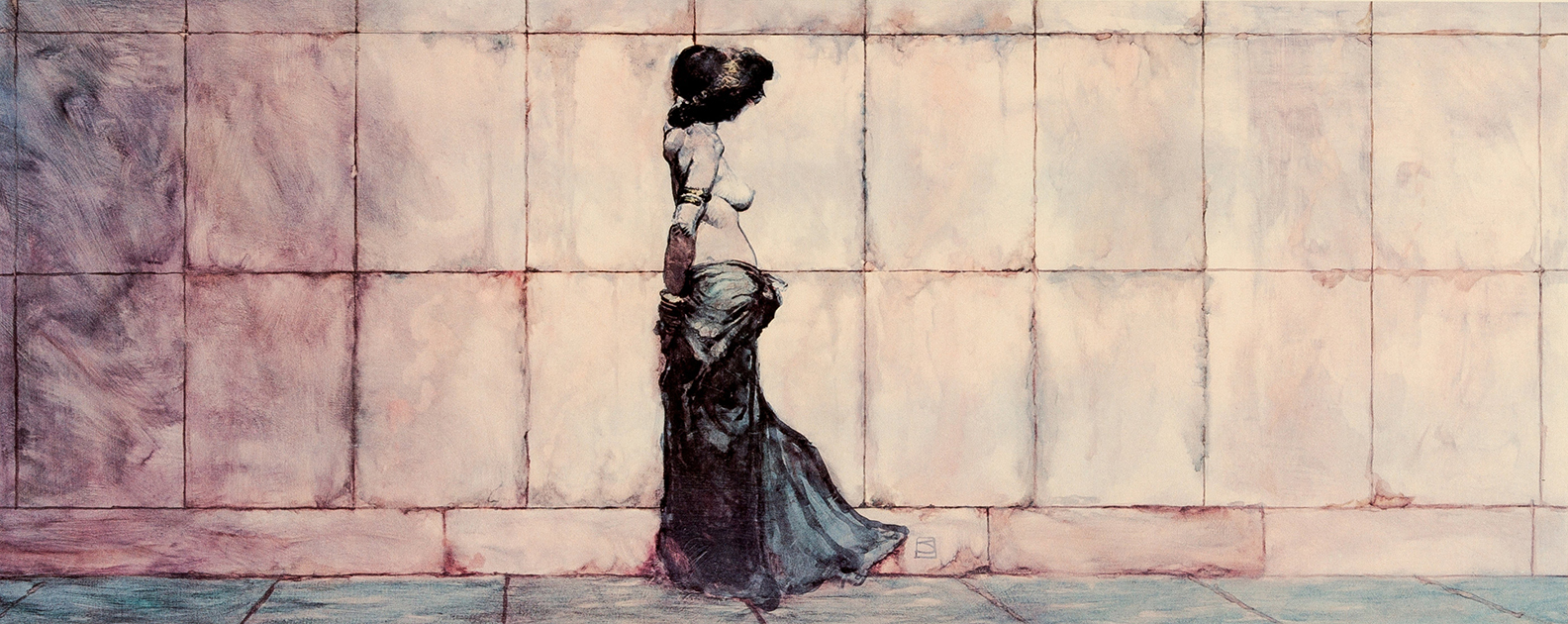

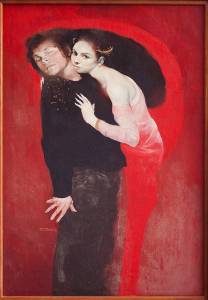

Though Jeff once said, “It is my firm opinion that Illustration is immoral,” many of his most remarkable and memorable works illustrated the fiction of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Robert E. Howard, Fritz Leiber, Lin Carter, and George R.R. Martin. His comics, including the satirical “Idyl” and “I’m Age” strips, are beautifully drawn examples of compelling storytelling—by turns whimsical, horrific, philosophical, or nonsensical—that were jobs for major publishers. When creating for himself Jeff would almost inevitably return to genre subjects and produce pictures featuring mythic warriors (like Solomon Kane and Tarzan), mermaids, and monsters. Even his paintings of women, whether clothed or nude, possess an impressive sense of narrative that have a close kinship with Illustration even as they transcend into Fine Art.

Jeff was often skeptical when told of his influence on young artists and could be dismissive when others spoke glowingly of his work and achievements; he sold virtually everything he created and, except for some sketches, kept very little of his own art. The next drawing, the next painting, always seemed more important than what had been finished.

Jeff began transitioning in 1998 and lived as a transgender woman until her death in 2011—as touched upon in my wife Cathy’s and my 2002 book The Art of Jeffrey Jones and as detailed in Maria Paz Cabardo’s excellent documentary, Better Things: The Life and Choices of Jeffrey Catherine Jones—but I routinely refer to Jeffrey as “he” when talking about his work. Why? It’s not a sign of disrespect but, rather, is at Jeff’s direction. “Catherine did not paint the paintings or draw the drawings,” Jeff told me in 2006 when presented with the Spectrum Grand Master Award. “Jeff Jones did; they’re the result of his efforts. Jeffrey Jones. That’s how people know me. That’s how I want to be remembered.”

As I said earlier, Jeffrey Jones was…complicated. Which, in a way, helps explain how special he was and is and why Jeff’s art—regardless of when it was created—intrigues, excites, and resonates with audiences today and will continue to do so in the years ahead.

Robert K. Wiener

I first met Jeff Jones in 1968 at the home of Donald M. Grant in Rhode Island. A friend had driven me down from Boston to buy some of the books Don was publishing. Jeff was there picking up the 4 paintings he had done for Don’s publication of Red Shadows by Robert E. Howard. This was Jeff’s first commercial commission which Don had given him after seeing Jeff’s display of art at the 1966 World Science Fiction Convention. At this point Jeff had been in New York City for less than a year, doing book and magazine covers as well as interior illustrations and comic book stories. I knew Jeff’s art first from his publication in Science Fiction and Comics fanzines and saw his early professional work as it was appearing in the book and magazine racks every month. I met Jeff for the second time a few months later at a Science Fiction convention. We got along well and

he invited me to stay with him and his family whenever I came down to New York. On these occasions I would usually spend a lot of time just sitting with him in his studio watching him paint and then accompanying him around the city doing various errands. Sometimes Jeff would convert his bathroom into a photographic darkroom and I would help him make prints of reference photos or of his original art which he would send to people who had expressed an interest in buying an orignal from him. Jeff held a monthly gathering of artists at his apartment and I would try to schedule my trips to coincide with these events. I would sleep on the couch in the living room. He told me that when he first moved to the city his goals were to do a book cover, a magazine cover and a comic book story. Those were he first three jobs he got and he had to quickly reconsider his goals. On one visit in 1970 he came into the room holding the cover painting to Vampires of Finistre. He said “Do you like this?” “Yes” I replied. “It’s yours.” he said. It took a few moments for me to get over the shock and thank him. That was my first Jeff Jones original. Throughout the 1970’s whenever I had any spare money I would buy art from Jeff. Fortunately he would accept time payments. It didn’t matter the size of the payment as long as you sent it when you said you would. I remember sending him $25 and $50 payments in those early years. Often Jeff would not want to sell a painting until he had done a few more. Some he held on to for a number of years. I have been lucky to have been in the right place at the right time to be able to get a number of paintings that I really love. In 1972 Jeff moved out of New York City to Woodstock, NY not to return until 1975. I remember him telling me that he had to move out of the city to get away from illustration work so he could figure out what he really wanted to do. Later he told me that when he first moved to New York he quickly learned how to make things look good and then he had to learn how to do it correctly. He certainly succeeded!

[Note: Robert has copies of Idyl-I’m Age and Cathy’s and my The Art of Jeffrey Jones, as well as prints and even an Idyl T-shirt, available at the Donald M. Grant website.]

When I entered art school in 1980 my aim was to be a comic book artist, pure and simple. Comic books were what really rang my bell. I had attended a year of university before going to art school, and though I didn’t take any art classes I was cranking stuff out like crazy on my own. There was a great comic shop in Austin, Texas (Austin Books) and I frequented this place because they had a great selection of books and they had Bernie Wrightson originals on the wall. And sometime during that year I stumbled on The Studio book featuring four of my comic book heroes: Bernie Wrightson, Michael William Kaluta, Barry Windsor-Smith, and Jeff Jones. Around that time, too, I picked up Yesterday’s Lily. These two books changed my artistic goals immediately. And it was Jeff’s work that really got me thinking about other things. Namely, painting.

When I entered art school in 1980 my aim was to be a comic book artist, pure and simple. Comic books were what really rang my bell. I had attended a year of university before going to art school, and though I didn’t take any art classes I was cranking stuff out like crazy on my own. There was a great comic shop in Austin, Texas (Austin Books) and I frequented this place because they had a great selection of books and they had Bernie Wrightson originals on the wall. And sometime during that year I stumbled on The Studio book featuring four of my comic book heroes: Bernie Wrightson, Michael William Kaluta, Barry Windsor-Smith, and Jeff Jones. Around that time, too, I picked up Yesterday’s Lily. These two books changed my artistic goals immediately. And it was Jeff’s work that really got me thinking about other things. Namely, painting.

All the work in The Studio pushed outside the borders of comics, which was fantastic. But it was Jeff’s paintings that took my breath away, stole inside me and rearranged the furniture in my head. I had always responded to paintings, even when loving up on comics. My parents had books on Pissarro, Sisley, Monet about the house. I gravitated to Rembrandt, Homer, Norman Rockwell, and, of course, Frazetta. But something about Jeff’s work dug deep for me, and he became the conduit, the gateway to the bigger world of art with a capital “A”.

Frazetta’s paintings were iconic, to be sure. I loved them. But Jeff’s paintings had something else. Hard to describe. Hard to nail down. But they lived in a different space that was emotionally deeper, for me at least. They were rich in self-reflection, a mood at once quieter, contemplative, and more viscerally honest. And as much as Jeff wore his influences on his sleeve, the pieces exuded Jeff himself.

I began to haunt used bookstores to snag Jeff Jones covers. I became so adept at this I could recognize his books just by the spines. My collection grew and grew. So I get to art school and those two books became my bibles. My copy of Yesterday’s Lily is dogeared and well worn, much loved. I remember taking it into class and showing my professors the work inside. They all knew who Jeff was. They all acknowledged that he seriously knew his shit. That was wonderful to hear because comics were totally frowned upon. I remember my anatomy teacher, the great Sal Montano, looking through my copy of Idyl and Yesterday’s Lily, nodding his head, and exclaiming immediately that Jeff’s work was beautiful and that he was good stuff to study.

My closest painting buddies at Pratt Art Institute in 1980 were Kent Williams, Ed Lee, and Sherilyn VanValkenburg. We were on fire! Everything we did was in service to our struggle to learn how to draw and paint. Everything! And Jeff was the star we set our compass by (we set our compasses to many stars, actually, but Jeff was the North star). After showing him some of our work he graciously invited us to join him for landscape painting in upstate New York. For us this was tantamount to painting with Rembrandt and we lost no time in hustling up there.

My closest painting buddies at Pratt Art Institute in 1980 were Kent Williams, Ed Lee, and Sherilyn VanValkenburg. We were on fire! Everything we did was in service to our struggle to learn how to draw and paint. Everything! And Jeff was the star we set our compass by (we set our compasses to many stars, actually, but Jeff was the North star). After showing him some of our work he graciously invited us to join him for landscape painting in upstate New York. For us this was tantamount to painting with Rembrandt and we lost no time in hustling up there.

What a time we had. At the crack of dawn Kent Williams, J Muth, Bernie Wrightson, Dan Green, Allen Spiegel, Jeff and I would pile into various cars bristling with easels and drive to a location Jeff had picked out a week or so before. Mist shrouded the roads that wound up the Catskill mountains and we’d tell ghost stories as we drove along, scaring each other pretty well. Scarier still was watching Jeff work. He opened my eyes to the true joy of painting. He never taught, but over the years dropped nuggets of information, crystallizing everything I had been struggling for; miniature bombshells that had me convulsing in artistic fits for weeks afterwards. He took the time to look at the work and respond to it in a positive way, which meant the world to me, and I grew. What I walked away with was the idea that art is a spiritual journey of the heart.

Jeff was the painting teacher I never got in art school. I made the mistake of switching majors near the end of my time in art school from illustration (where we were actually given lots of instruction in skills and media) to Fine Art, where they basically didn’t really teach anything. So Kent and I taught ourselves by going out and landscape painting, and hitting the Brandywine River Museum to scope out NC Wyeth and Howard Pyle and Harvey Dunn. And go painting with Jeff in the Catskills.

Jeff wrote about landscape painting: “This is one of the reasons I love to paint landscapes. It takes problem-solving out of the work. In the studio there’s a lot of problem-solving that goes on because so much of it has to come out of my head. I have to make it work, because it doesn’t exist and you can’t go out and look at it. When I’m out there landscape painting all I need is right in front of me, and there’s nothing that needs to be in my head. It’s like a vacation from my studio. It’s rejuvenating in the same way a vacation is. I had to get used to it, because it wasn’t familiar, the wind and the bugs. I’d put a paint rag on the end and it would blow off, all those kinds of things. I finally realized they were only excuses not to be landscape painting; they weren’t really reasons at all. I didn’t want to come here in the first place, so look at all the excuses I can make up not to be here. What would happen if I came out because I wanted to? Funny thing… I didn’t find any excuses!

Jeff wrote about landscape painting: “This is one of the reasons I love to paint landscapes. It takes problem-solving out of the work. In the studio there’s a lot of problem-solving that goes on because so much of it has to come out of my head. I have to make it work, because it doesn’t exist and you can’t go out and look at it. When I’m out there landscape painting all I need is right in front of me, and there’s nothing that needs to be in my head. It’s like a vacation from my studio. It’s rejuvenating in the same way a vacation is. I had to get used to it, because it wasn’t familiar, the wind and the bugs. I’d put a paint rag on the end and it would blow off, all those kinds of things. I finally realized they were only excuses not to be landscape painting; they weren’t really reasons at all. I didn’t want to come here in the first place, so look at all the excuses I can make up not to be here. What would happen if I came out because I wanted to? Funny thing… I didn’t find any excuses!

“Nobody has to see it and you know it. If you like it, you like it; if you don’t, you don’t. That’s the end of it. There’s no deadline, no patron, no nothing. I wish everything could be as fun as a landscape, but everything is not. The more fun I’m having, the more I want to paint and draw.”

Jeff was able to distill everything to its most simple and direct expression. This is obvious in his paintings and in his black and white work. Idyl is powerful in its simplicity. Mostly because that simplicity is incredibly deceptive — there’s nothing simple about them. How jeff was able to boil the forms down, to jettison so much to make something more powerful is mystifying. It was exhilarating to see, and to try and emulate. It taught us how to see, how to edit our own pictures. In person he was a reluctant teacher. He didn’t want to steer anyone wrong. But if you caught him off guard the info would overflow. He would talk about limited palettes, and how each object is a volume of air. How when you’re painting you’re not painting the object but the air between you and the object. Heady stuff that took a lot of time to struggle through, but worth its weight in gold.

And on top of all that Jeff was a gentle person who took the time out to help a young artist navigate difficult waters.

I owe Jeff a considerable debt for helping to mould me into the artist I am. His work lives on and continues to influence countless artists, budding or professional.

One of my all-time favorites.