by Arnie Fenner

How do you find a publisher, particularly if you’re playing rōnin and representing yourself without an agent?

Research.

If you’re already working in the field in some way, painting book covers or gaming cards, you already have some sort of relationship with an art director or editor: it never hurts to tell them what you’re thinking of and ask for suggestions. Provided you’ve been a pro and gotten along well, most are willing to provide tips and perhaps make introductions.

But let’s say you don’t already have a connection in the industry. First, note the publishers/imprints for books along similar lines to what you’re planning to do by searching online or looking at catalogs or visiting bookstores. Peruse both the art and genre sections (or children’s book departments if that’s your focus) to find out who is doing what. Amazon is a given, but Bud Plant and Stuart Ng are both great starting places; your local Barnes & Noble or independent bookseller are wonderful resources.

Once you have a rough list in hand you can begin to research specifics: submission guidelines, preferences (will they take submissions via email or strictly as hard copies?), and contact information. Everybody has a website, but books like Writer’s Market—and Artist’s Market and Children’s Writer’s & Illustrator’s Market, too—can save you a lot of time and be quite useful (though given changes that can take place between the compilation of material and publication they’re never 100% accurate).

The list of publishers who either specialize in or have lines devoted to art books is long and should probably be the first you pitch your proposal to, but there are also publishers who sort of “dabble” and produce an art book occasionally when it seems to fit in with their programs. Boris Vallejo’s first book was released under the del Rey imprint and Rowena Morrill’s came out from Pocket and neither publisher were (or are) particularly known for their art monographs; comics giant Dark Horse is responsible for wonderful books by Charles Vess and Eric Joyner so you can’t really cross any publisher of your search list without doing your homework. No one can know everything, no one can know everyone, but networking with fellow artists—purposefully going to conventions and exhibitions where publishers, editors, and art directors are in attendance—will provide contacts, suggestions, and insights that you’ll never get sitting at home cruising the internet by yourself. Remember, publishing is personal and a little face time at a show can open some doors that might otherwise seem closed.

Fair Use. What can you put in your book once you’ve got it sold? What can’t you? I’m going to take a deep breath and try to keep this as brief and clear as I can in the most general of ways: please keep that in mind.

Essentially, the Fair Use Doctrine grants limited use of material copyrighted by others without getting the permission of the rights holder. Sometimes the owners grouse, sometimes they have lawyers rattle sabers and send Cease & Desist demands to try to scare the users, and sometimes, yes, they sue in the hopes of attaining a settlement to their satisfaction without actually going to trial. Because believe me, corporations or estates or individuals never want to go before a judge and/or jury in a Fair Use case. Why? Litigation is horribly expensive no matter which side of the fence you’re on, the outcome is never predictable—and, historically speaking, the legitimate Fair Use defense wins cases more often than it doesn’t. Lawsuits are public records and if you lose…everyone knows it. Routinely Fair Use is used for works of criticism, parody, news reporting, education, research, historical documentation, archiving, and scholarship. Title 17 of the United States Code of Copyright, Section 107, outlines the “four factors of analysis” that the courts use to determine the difference between Fair Use and infringement. What are the four factors? Click and read.

Damn. That all sounds complicated, doesn’t it? Well, that’s because it is. As with all aspects of the law, everything is ruled by specific statutes and legal precedent and the interpretations of same. What might seem like absolutes are only such until challenged—which is why there are no black and white absolutes when it comes to the law, but rather constantly evolving interpretations and reinterpretations as new additions are made and new precedents set.

Okay, let’s look at this several different ways. You’ve been painting book covers and want to do a collection of them. Unless there’s been some weird language in your purchase order or contract, you can do whatever you want, not only with a book, but with prints, calendars, T-shirts, or whatever. It does not matter whether you’ve been illustrating Harry Potter or Game of Thrones or anything else that has a high profile and possibly multiple licensing programs, if you didn’t reassign your copyright the art is yours to do with as you will—and that includes putting them into a collection of your art. Within, naturally, certain parameters.

You can’t design or market your book in such a way that it causes confusion among consumers. It’s easy to muddy the waters and inadvertently imply authorization or license from a legitimate rights holder, either corporation or author, where none exists—and that’s a huge no-no.

Say you’ve painted 50 Stephen King covers as a freelancer; you can certainly take them all and put them in a book, but you can’t market it in such a way as to make it seem like a Stephen King book. You can’t emblazon *STEPHEN KING!!!* big on the cover and you can’t imply in some way that King is somehow intimately involved unless you enter into a license with him. (If someone wants to do a book about King, including any illustrations based on his fiction, that falls in the realm of “scholarly” or “educational” purpose and is permitted under the Fair Use doctrine, including the use of King’s name in the title—”The World of Stephen King”—but obviously not as the by-line. Again, it’s about King, not by him and that has to be made crystal clear to the average Joe looking at the book.)

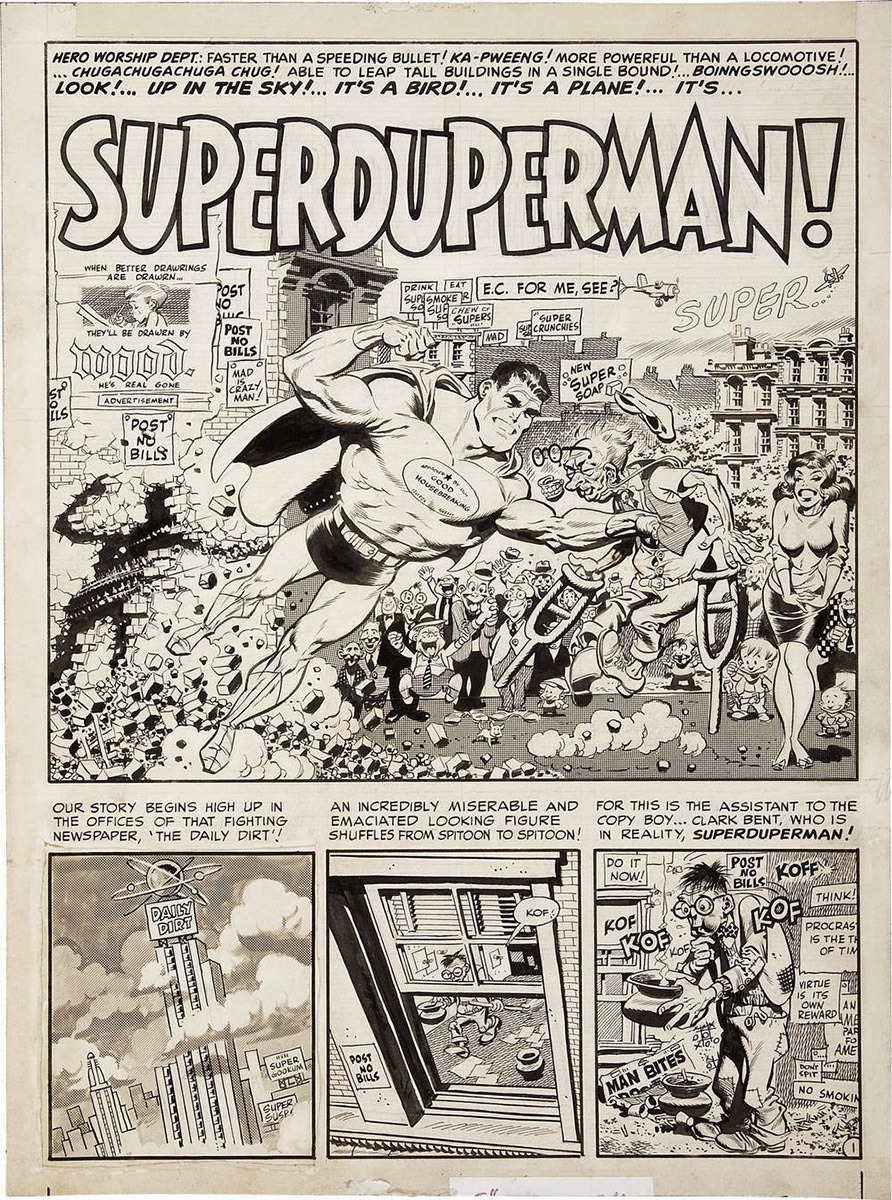

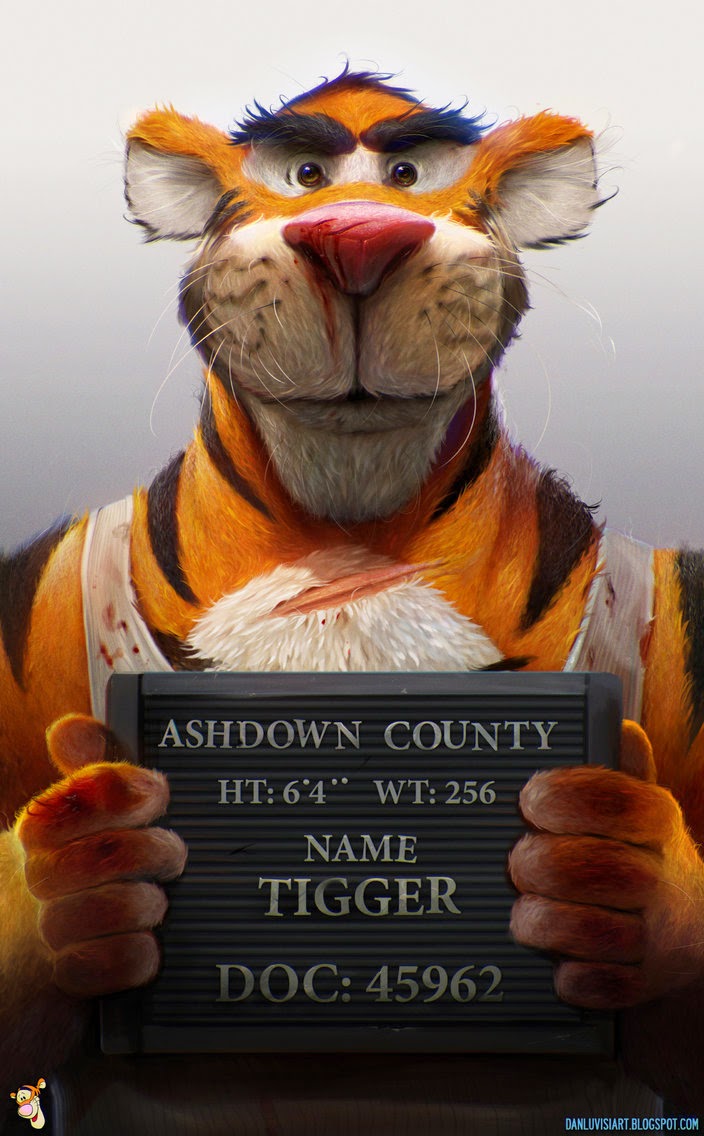

Someone had asked earlier about Dan LuVisi’s series of revisions of iconic cartoon (and Sesame Street) characters that formed the basis of a gallery show and which were widely distributed on the web: how is that allowed? Easy: the works were transformative—reinterpreting (editorializing in a sense) the characters in an entirely different way from their original incarnation or intent—and as such, protected as Fair Use. He did not merely copy characters, he changed them significantly allowing for a different context and evaluation, prompting a new “conversation.”

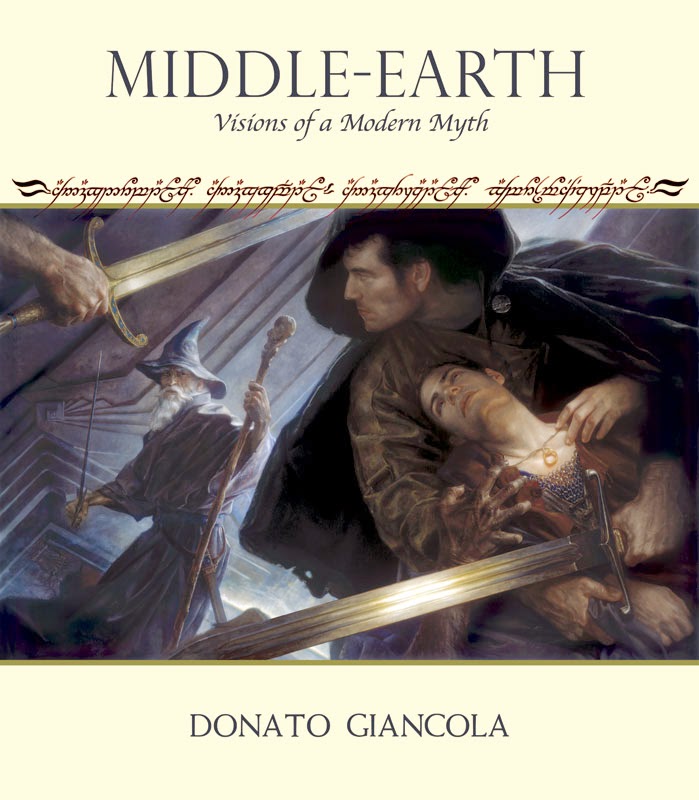

Similarly, Donato’s Middle-Earth: Visions of a Modern Myth is transformative (and thus protected by Fair Use) because he was revisioning J.R.R. Tolkien’s words as pictures, providing his own personal commentary and analysis and discussing the illustration work he had done for various publishers. Tolkien and his publishers never created a “Lord of the Rings” character art style guide for licensing (thus locking in a specific look that could be copyrighted) to cause concerns of infringement. Virtually all of the character descriptions—from Gandalf’s pointy hat to the features of the Orcs—are generic and Public Domain by this point and Tolkien’s name does not appear on the front cover or in Middle-Earth’s marketing (so there is no confusion of authorship) nor does his text appear in the book. Donato’s book bring’s something new, unique, and ultimately valuable for readers to the table and, as such, is permitted.

As mentioned above, if someone—author, estate, or corporation—wanted to sue over a similar project, there’s nothing to stop them (other than common sense). Including a credit to copyright owners is not an invincible protection against litigation. This is America: we sue all the time, regardless of grounds. Some estate owners of works that have lapsed into the Public Domain have tried to maintain control over the properties (and demanded fees for permissions from users) by trademarking unique names in the works willy-nilly and there are still cases winding their ways through the courts determining whether copyright status trumps trademarks: we’ll see what happens (the Betty Boop case is one of the most interesting to watch). For the most part it’s an attempt to game the legal system by intimidating plaintiffs with less money fearful of fighting a costly legal battle, but recently the Supreme Court let stand a Court of Appeals ruling that the bulk of the Sherlock Holmes characters and stories published prior to 1920 were in the Public Domain. In a repudiation to the Arthur Conan Doyle estate, Appeals Court Judge Richard Posner stated, “The Doyle estate’s business strategy is plain: charge a modest license fee for which there is no legal basis, in the hope that the ‘rational’ writer or publisher asked for the fee will pay it rather than incur a greater cost, in legal expense, in challenging the legality of the demand.”

You can be sure that the “owners” of other Public Domain characters had a stiff drink when the news came out.

One of the more famous cases in which an author won a lawsuit against a publisher of a transformative/Fair Use book was J.K. Rowling’s/Warner Bros.’ 2008 suit against RDR Books for the Harry Potter Lexicon. Ms Rowling prevailed not because such a book was not allowed under Fair Use, but because the author had used too much of Rowling’s copyrighted text in it. In his ruling for the author Judge Robert Patterson rejected many of lawsuit’s rights assertions and was careful to say, “While the Lexicon, in it’s current state, is not Fair Use of the Harry Potter works, reference works that share the Lexicon’s purpose of aiding readers of literature generally should be encouraged rather than stifled.” RDR subsequently revised the book, removing Rowling’s text, and republished it in 2009 without challenge.

But what if you have signed away your copyright? Say with art for game cards or comics or advertising?

Well, you can still use the art (at least some of it) in your book…with limitations.

As mentioned earlier, a collection of an artist’s work is generally seen as historical, educational, and as scholarly reference. If part of your career includes concept art for, say, Avatar or drawing covers for The X-Men you are allowed to include some examples in a retrospective book about your career with the proper copyright credit. Precisely how many pieces you can use without needing permission or tipping over to infringement is a little murky: percentages are sometimes cited, but they’re largely meaningless and nothing is carved in stone. Basically, “some” (perhaps 10–15% or so of the art in a book owned by another single rights holder) is generally viewed as “okay,” whereas “a lot” will probably illicit an angry legal response. What you definitely can not do is publish a book of only your Avatar or X-Men art without the permission of the copyright holder. Nor can you use any work that is copyrighted by another for your book’s covers or in the advertising for same: such usage confuses consumers as to the actual ownership of the property as well as infringes on rights sold to other licensors (it’s competing with them by using their own property) and is not allowed. Fair Use flies out the window when such use undermines the rights of the legitimate copyright owner.

When in doubt, it never hurts to talk to your clients, tell them what you’re planning, discuss any concerns, and get formal permission of use in advance. Remember, publishing is personal and most are willing to work with the artists. Yes, sure, you’ll encounter the occasional buttmunch; there are some clients who behave like the albatrosses in Finding Nemo chanting “Mine! Mine! Mine!” as a matter of course even though they don’t have any legitimate claim. Better you find out who the potential troublemakers are in advance rather than be blindsided by a letter from some legal department down the road—and you can always secure the services of counsel to negotiate use on your behalf if your own attempts have stalled. But for the most part, clients tend to be cooperative and helpful, particularly if you’ve maintained a good relationship.

Likewise, you can not whip up a bunch of paintings featuring Marvel superheroes doing typically Marvel superheroes stuff and publish them in a book, regardless of if you’ve ever worked for Marvel or not. That’s blatant infringement; there’s no parody, commentary, transformative, or historical context, it’s merely trying to cash in on something you don’t own. As I said with my earlier post about copyright, an artist can draw anything they want any time they want, but there are limitations as to what they can legally publish or somehow distribute. The artist has to create something new, create an entirely different context and understanding, something (as I said) transformative, not merely capitalize upon the work of or exploit the property owned by others.

Painting Batman fighting the Joker is not transformative; painting Batman marrying the Joker could be (provided DC didn’t already do it themselves).

Yes, you can go to conventions and see any number of artists selling sketchbooks filled with new drawings of various companies’ characters without their permission, but that doesn’t mean it’s legal. Those artists are gambling that they’re flying under the copyright owner’s radar and can get away with it—and for the most part they are and do. But anytime Disney or Warner Bros. or any other rights owner wants to crack down, they can. And you do not want to be standing at Ground Zero if they drop the bomb.

That’s the bare bones of Fair Use. Naturally there are plenty of grey areas and if you have any questions or worries regarding a project, definitely seek advice from an attorney well-versed in copyright and intellectual property law.

You're my hero

Thanks Arnie! You always do a great job of simplifying those confusing areas of copyright law and the publishing world in general. Appreciate it.

This is an excellent explanation of a subject that is not well understood by most of us. Thanks for posting Arnie.

First off, Thanks for clearing some of this stuff up. As a pre-professional artist I find this stuff super interesting and useful to know.

With that being said, I think there might be a slight typo in the bit about Donato's LotR art book. Or if not, Congrats Dan! I'm not sure how you did it (some how made Donato's book with his art about your art) you crafty magician you!

But yeah, thanks for the article, I enjoyed it greatly!

Awesome and thanks for answering my question about Dave LuVisi's work. The more you hear it or read it in examples, the clearer the mud gets 🙂

Thanks! I'll probably do something about how books are distributed (and why it's virtually impossible for self-publishers to get their books into mass-channels these days) or things to be aware of when crowd-funding a book, but we'll see.

Oh, and “Dan”? I wasn't accidentally referring to our Overlord Dan dos Santos. “Donato” is a professional moniker, but the illustrious Mr. Giancola's first name is also Daniel. He's been known to answer to “Hey, You!” too 🙂

Thanks Arnie for this fantastic and enlightening post …

One question … what you mention regarding book Donato … is similar to the book of Sanjulian , “Swords Edge” ? … Here you mention Robert e. Hodward on the cover.

I 'm a big fan of both artists , and I would be interested to know something about it.

A greeting .

Josep .

It's essentially the same. Howard's name is clearly used as a description of content, not as a by-line, but Conan Properties, Inc. and Underwood Books also have an agreement regarding use.

This would be very interesting. I have big goals involving self publishing etc and would love to get your take on it.

Thanks for answering Arnie … Regards .

Josep .