Looking back at the interviews that I’ve done with artists over the years, my studio visit with Robert Heindel is one of the most memorable and influential to me. I am forever grateful to Robert for letting me into his artistic life for one magical day. His insights, life lessons and creative journey as an illustrator, artist and educator have resonated with me. He was fascinating to listen to and even more interesting to watch. After the interview, he brought me into his studio: an amazing wall-to-floor sanctuary of artistic expression. Spanning across the room, figurative paintings on canvas came alive with color and gesture.

Although the original interview was focused on montage illustration, the artist and I talked about many things that day. I feel honored to have had the opportunity to visit with him at his Easton Connecticut home and studio back in April of 1997. The following article highlights some of the creative insights he shared with me that were never brought to a public forum. Unfortunately, Robert is no longer with us but his words break through like whispers of greatness. I hope his wisdom inspires you like it has me!

As a commercial illustrator, Heindel was a master at not only creating thought-provoking concepts but also captivating the viewer with engaging visual narratives. A unique combination of graphic abstract expressionism with moments of painterly realism, the artist’s work has a style all its own. “Pictures have to have an overall interesting shape and idea,” said the artist. “I will look for a strong element that everything else can support. It has to be something that will get attention. After that, I am adding and subtracting elements that will further enhance the piece. The elements and the colors need to be very relevant to the concept and meaning of the work.” Heindel’s process was very fluid and he rarely did preliminary sketches or thumbnails. “I could never follow them,” he added. “The client would see it (the sketch) and say ‘hey that’s great’. Then, I would go back and want to change it. As you work, you start to realize that this should have been bigger or that should have been over there. I think you should leave yourself room to change things. For me, pictures evolve. A good art director will give you freedom and be willing to go into a meeting to fight for you.”

During his illustration days, Heindel worked in a lot of different artistic media. “The deadline always dictated what you did. It was a classic case of using whatever worked,” added the artist. “I relied greatly on accidents. It was crazy and I always got in trouble in the last fifteen minutes of a job.” Working on gesso-primed or raw linen canvas that was either tacked to a wall or mounted onto gatorboard, Heindel’s process started with drawing in charcoal and pastel, creating an underpainting of sorts. After sealing the surface with fixative, the artist commenced to paint on top of the atmospheric environment with oil-based paint, often house paint, in thin veils of color. In his fine art, Heindel worked on several pieces at once. Each painting was signed using a stamp of a rose to symbolize the love for his wife Rose. When complete, all of his pieces were framed under glass. The artist liked the way the glass reflected the viewer and the space into the piece. “I put glass on my work because I want people to be reflected in the picture,” he said. “I demand active participation in my work. It’s part of my thought process and what I think about emotionally.”

Heindel shared with me some of his biggest artistic influences: Pierre Bonnard, French painter and printmaker, and Cy Twombly. You can see the color palette and mark-making connections between the work of Heindel and that of the two fine artists. In addition, he also considered the motion picture industry as an influence in his work. Throughout his career, Heindel was attracted to the work of illustrator Bernie Fuchs, seeing his work as the yardstick in which to measure excellence. “I admire anybody who is brilliant. I look at Bernie and think about how, as a human being, was he able to do that and wonder how he evolved,” said the artist. “Bernie had so much impact on the business. He showed them all how to do it. Mark (English) would be the closest to that. Fred (Otnes) was also tremendous, but more specific.” As friends, the group of illustrators lived close to each other for many years, often modeling for each other and competing for the same assignments. “To compete with people that are great is a lot of fun, but they can beat the shit out of you sometimes!” laughingly recalled the artist. “At one point, Mark English and I were forbidden to do Spiro Agnew and Richard Nixon. We hated them so much that it kept showing up in the work. We would even call each other on it. Those kinds of things were what was fun about being an illustrator, because you were caught up in major events.”

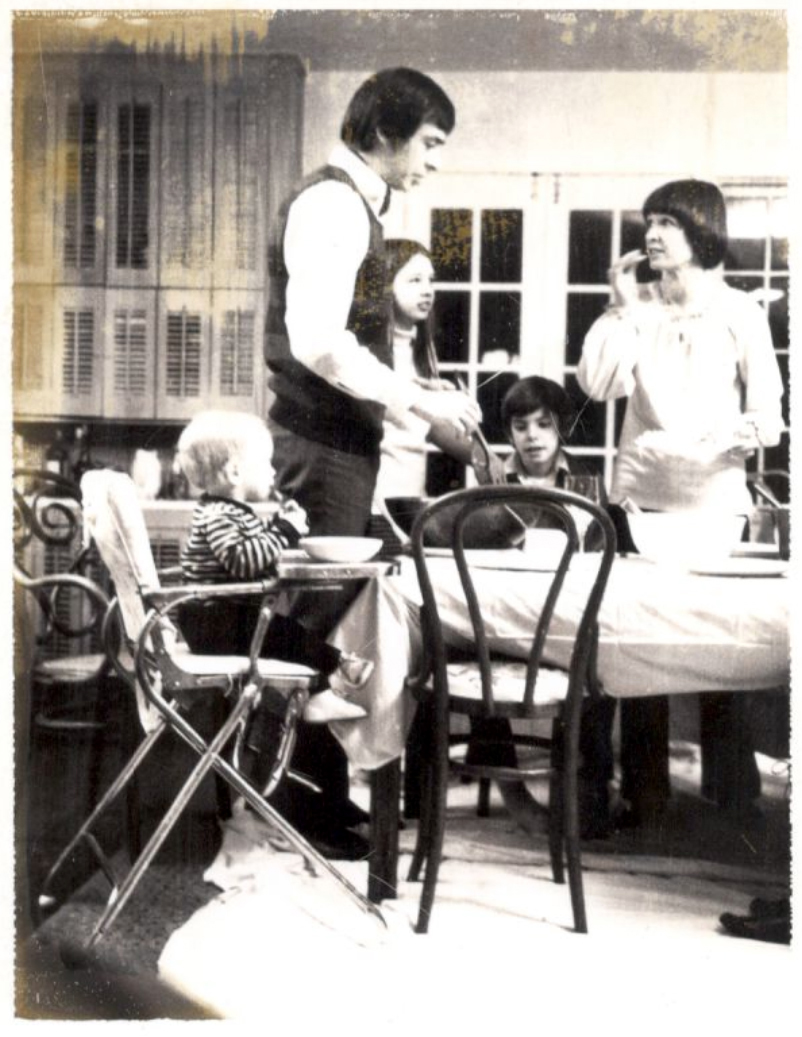

Shown is a photo reference of Robert and Rose Heindel shot by illustrator and friend Mark English for an editorial illustration. Photo courtesy of John English.

This photo reference shot by illustrator Mark English features Robert Heindel, Peggy English (wife of Mark English), Stephanie English (daughter of Mark English), the young boy is Toby Heindel (son of Robert Heindel) and the toddler is a friend of the English family. Photo courtesy of John English.

Over the span of his illustration career, Heindel has had some very interesting and exciting projects. “Over the years, I got a lot of great assignments. I was very fortunate,” said the artist. “Once I did a Time cover of an event where a kid was kidnapped and buried in a box in the ground. It was extraordinary and shocking that I was even involved in the event.” The artist recalled another Time magazine cover project and said, “It had to do with the pentagon and I had the only photo in the world of it. The lunacy of twenty-some-odd hours of limos coming in and out of here, someone sitting there next to me and all the phone calls was just absolute craziness.” When it came to editorial work, Heindel liked a great story. “In editorial, you are dealing with ideas. If you don’t have a great script, there is not much to do,” said the artist. “You are always looking for something that isn’t a woman sitting with a cup of coffee, contemplating her fate on the planet. Those stories were boring after a while.”

As a gallery painter, Heindel’s focus was almost exclusively on dancers. He was fascinated by their ability to translate emotions with their bodies, adding beauty, elegance and strength to his paintings. The artist saw every theatrical performance as a way to express something from a different perspective. “Each dance company, dance and dancer have their own particular style. Whatever they are about, you’ve got to leave yourself open to it,” he added. “The (dance) groups always know who is who in my paintings. They don’t know by face, but by the way they move.”

For Heindel, research was a very important part of the creative process. When working on a series of paintings for a dance, he would take lots of photographs as well as make small sketches and notations to document the experience. He believed that one must take part in the process in order to communicate what had transpired. “To paint dancers, I take tons of pictures, recording thoughts on camera. It’s fixing in your mind everything that is going on and not just the people,” he explained. “The more you know about any subject, the better you are going to be at painting it.” While working, Heindel had great access to the dancers he painted. “I am allowed in to watch the dancers. They know who I am and I get to observe them while they work,” shared the artist. “Although I have a great advantage in terms of access with my camera, shooting dancers freeform is difficult. You can’t control the light or the space. You use what is existing and make that work for you. It’s an extraordinary opportunity and you get caught up in it all.” For Heindel, first-hand knowledge and engagement with a subject set the stage for strong, emotion-based image making. “I certainly have preconceived notions on what is going on. But, I think, you try to go blank so you can let whatever is trying to happen, happen. You have to smell it and feel it. You need to become part of it. It effects the pictures when you know all the details. I think that is important,” added the artist. “People look at what you’ve done and walk away knowing that there is something in there that is haunting. That’s what artists should do. They trigger responses in the nervous system. I love to look at paintings that evoke some past memory or emotion and you don’t know quite what it is.”

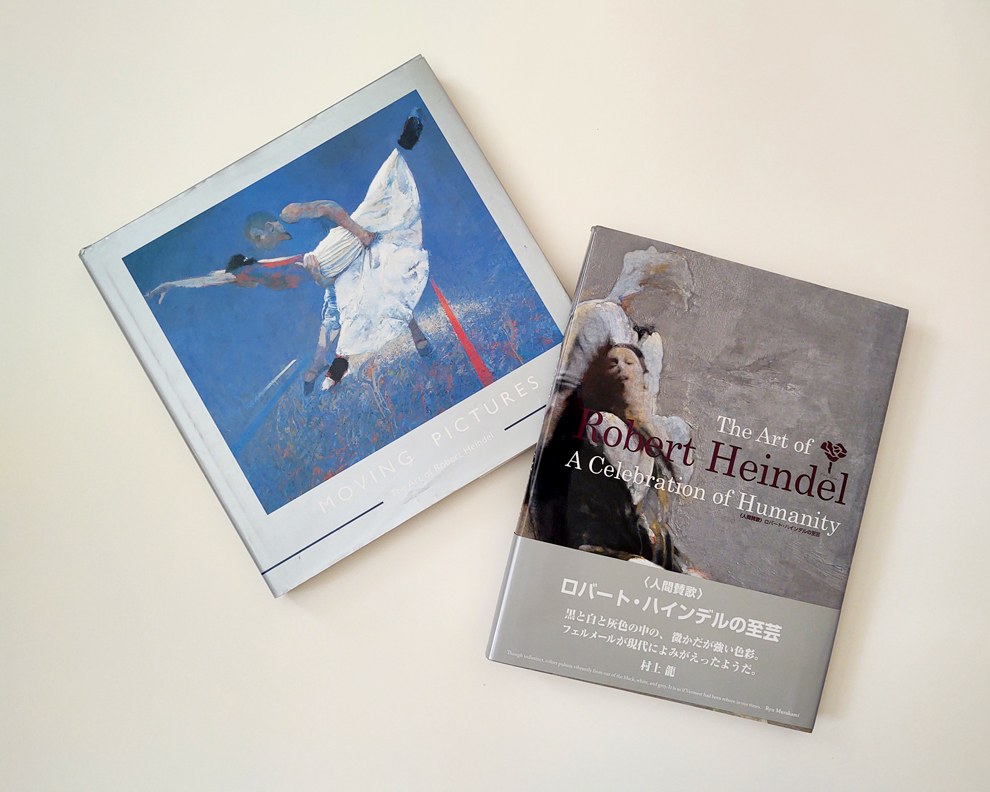

Featured are a few books on Robert Heindel that my husband was able to purchase for me at The Obsession Gallery in Tokyo Japan.

The artist compared the on-location experience to his illustration days and said, “In your average illustration, you are relying on reference that the client gives you and what you can find. It’s not that great first-hand understanding.” Heindel recalled a story of a musician he met, “When I went to see him play, I became emotionally involved. It is a different experience. It’s not that he was playing any better or that he looked any different. It is that I was now personally involved. I like life at that level. I don’t like things second hand.” Heindel also described the illustration business as a business of seconds. He explained, “As an illustrator, I was in the business of communications where there would be seven seconds to get someone’s attention. I also had very little time to get things done. The illustration business is attracting clients and making deadlines. It runs the gamut. As an illustrator, I was never confused about doing a piece for the Sistine Chapel. It was the Ford Motor Company and that was it. You were given an assignment and you were solving someone else’s problem. As soon as it was done, that was it. The illustration had served its purpose and you were off to something else. With these pictures, (referring to his fine art), if somebody buys them, they have a lifetime to digest every square inch. So, as an artist you are hopefully saving the shocks for little tiny places all over. What sometimes may be no work at all is the most extraordinary part.”

One of the most ingenious things about Heindel was his entrepreneurialism. When most illustrators were relying on agents and fine artists on galleries, Heindel chose the road less followed. Instead of looking at the market trends, he looked inward. Having a passion for art, music and dance, Heindel ventured out on a leap of faith, traveling across North America to meet with dancers and dance companies. His idea was to work in collaboration with the various performance companies, negotiating creative ways to work together that were mutually beneficial. The Obsession of Dance Company was formed as a result, propelling Heindel and his work into rock-star status. From his efforts, the artist had the opportunity to work on many theatrical productions, including Cats, Penguin Café, Dance House, Les Miserables, Phantom of the Opera. At the time of this interview, Heindel and his wife Rose owned and operated The Obsession of Dance Company, which published limited-edition prints of Heindel’s work as well as the work of other artists like Fred Otnes. Outside the United States, the company had branches in Holland, Great Britain and Japan. Today Heindel’s work is curated by his son Troy Heindel. You can see his vast body of work on the dedicated online site called The Robert Heindel Museum of Art. Over his vast career, Heindel has had several one-man exhibitions all over the world, including the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC and London’s National Portrait Gallery. His work is in many private and public collections. Hall of Fame illustrator, Heindel has also been honored by the Society of Illustrators in New York City with the Hamilton King Award for the work he did for the Dallas Ballet Company.

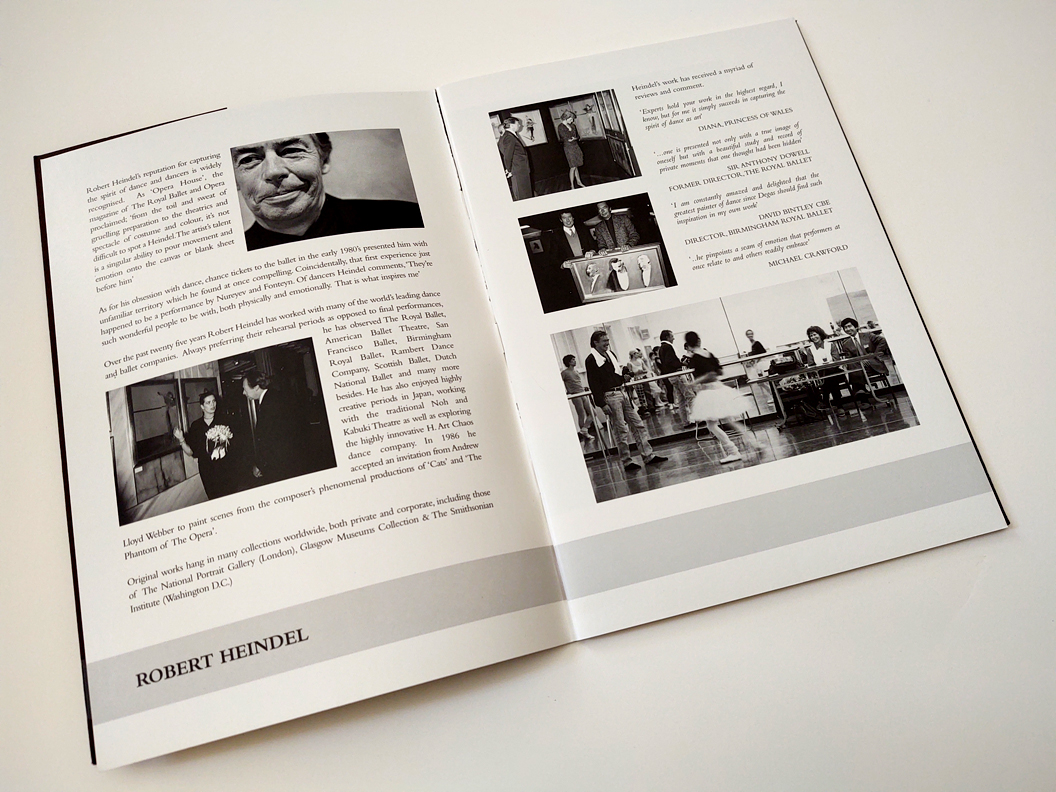

This is an inside spread from the catalog shown above. It features Heindel with the dancers as well as with Lady Diana and Princess Caroline.

In addition to being and illustrator and fine art painter, Heindel was also a teacher. He and a group of illustrator friends formed what was known as The Illustrators Workshop. Heindel was one of the group’s founding members, along with fellow illustrators Mark English, Bob Peak, Bernie Fuchs, Alan Cober and Fred Otnes. Remembering the workshop days, the artist said, “The Illustrators Workshop was great fun with good friends. We always tried to teach the students to find their own thing and do it.” Many of today’s leading illustrators came out of the program, including CF Payne, Anita Kunz and Matt Mahurin to name a few.

The Illustrators Workshop, which later became The Illustration Academy, is no longer an on-ground experience. It has been transformed by John English, son of Mark English, and Timmy Trabon into a virtual training ground for illustrators and concept artists. Visual Arts Passage, offers live online classes and engaging content with leading industry professionals. “Starting a career in the visual arts can be a daunting journey and students are often tasked to navigate this rapidly evolving industry on their own,” offers Trabon. “Visual Arts Passage was founded to demystify this winding path by connecting students with world-renowned, working artists as mentors. Our custom-tailored mentorships act as an industry compass, helping students establish critical skills and techniques, as well as develop a finished portfolio that aligns with their professional goals.” The online program is specifically designed to bridge the gap from the student to the professional, fostering opportunities to network and build real relationships with the best working artists in the business. “The carryover from the Illustrators Workshop is the importance of students learning from industry artists, with a focus placed on the development of a personal voice, an in-depth understanding of the industry and a professional, market-driven portfolio,” adds English. Students of the program are making their own waves in the field, boasting numerous medals and awards from the Society of Illustrators and Spectrum Fantastic Art. Most recently, illustrator Miriam Matincic was awarded a Gold Medal by the Society of Illustrators in New York City. The program has been listed on the Best Online Art Schools and Best Online Concept Art Schools by Imagine FX Magazine. In addition to Visual Arts Passage, an extension program was recently created called Studio Bridge. Each month a different illustrator or art director offers an in-depth look into their trade though weekly livestream demonstrations and lectures. The program also offers a free figure drawing event every Thursday called Illustration Isolation.

When asked about the big breakthroughs he had in his career. Heindel responded, “I’ve thought of that over the years. It’s not exactly like it is in show business. It’s not like doing a hit movie. I think what we do is more gradual than that. I think we have many breakthroughs in our style. Like events in our life, it’s a lot of incidental things. I think it takes a long time to develop your style. It takes a long time to develop your own personality and your style is simply an extension of that.” Heindel got his artistic training from The Famous Artist School, studying commercial art. Years later, the artist was appointed to their advisory board, becoming one of their greatest success stories. “Initially, I very much wanted to be an illustrator. I didn’t have any ideas about being a painter,” shared the artist. “I think that had a lot to do with growing up in the Midwest and not understanding that you can make a living as a fine artist. It wasn’t until I got to be about forty that I started to see myself become less and less of an illustrator and more of a fine artist.” For Heindel, the fun was in the journey. “The destination is not important. You are going to go through a process and that is what is going to mean the most,” he said. “I get up in the morning and I make pictures. I find it interesting and I have a lot of freedom. I draw and paint for myself now.”

copyright 2021 Lisa L. Cyr, Cyr Studio LLC

So glad you got to interview an artist who opened up their creative space and had profound effect on you Lisa, I’ll bet that’s a experience you cherish everyday!

Personally one of my favorite parts of painting a portrait is learning as much as I can about the subject, I definitely believe in “The more you know about any subject, the better you are going to be at painting it.” 🙂

Thank you Brian. I am so lucky to have had so many great opportunities to experience illustration royalty! First-hand knowledge with a subject is so important. So happy you enjoyed the article!

Love it. Learning about illustration’s Rat Pack is always fun. Heindel’s work is gorgeous. Thanks!

YES the illustrators workshop gang and others were the rat pack of illustration! LOL! Heindel’s work, approach and business savvy are a roadmap to success!

Incredible post, thank you Lisa! I was fortunate to become close with the Illustration Academy team, and as a result became a big fan of Heindel. I own a few of his exhibition catalogues that I cherish. I particularly appreciate your note that he was educated via the Famous Artist School. I consider those among the best illustration resources ever, and this even furthers that, so cool!

I am so glad you enjoyed the post. It is so important to keep the knowledge of these illustration luminaries alive for the next generation!

What an amazing post, Lisa! Robert has always been one of my favorites, and remains so to this day. I regret never having gotten to know him, but this article brings me a little closer. Thanks for this wonderful write up.

Thanks Dan! It brought back so many great memories for me!

What a joy to read this, thank you for sharing—I hope to attend the live drawing via Zoom with Visual Arts Passage thanks to your link!

I feel like I got to meet the artist and man. Nicely written.