I didn’t know there was a word for this until recently, but of course there is, and of course it’s German.

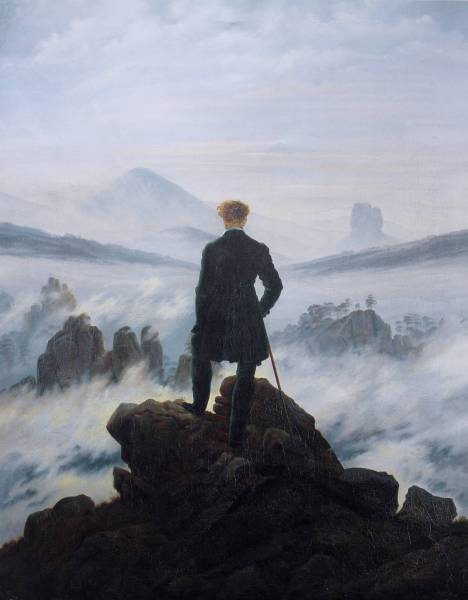

Rückenfigur (literally “back-figure”) is a compositional device in painting, graphic art, photography, and film. A person is seen from behind in the foreground of the image, contemplating the view before them, and is a means by which the viewer can identify with the image’s figure and then recreate the space to be conveyed. (from Wikipedia)

The textbook example of this is this image is Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog:

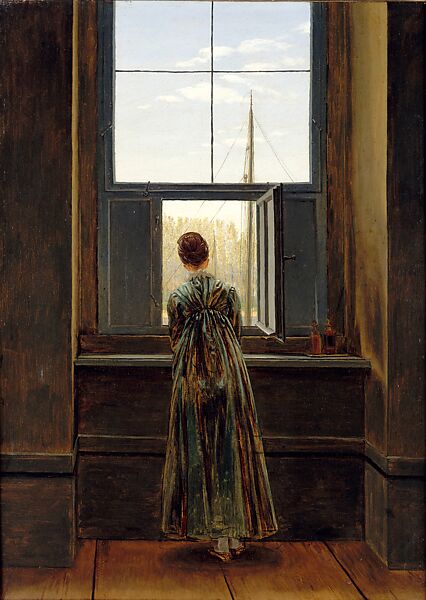

And in fact, I only heard the term Rückenfigur at all because there was just a Caspar David Friedrich exhibit at The Met. He loved this device and it shows up in his work a number of times:

Obviously Friedrich is far from the only artist to use this trick — he just used it a lot. Once you start looking for it you’ll notice it more. And it’s always used purposely to give you that feeling of stepping into a scene. Here’s another well-known example, in Andrew Wyeth’s most famous painting, Christina’s World:

No artist is going to choose to give us the back of a character accidentally. No artist is really excited about painting the back of someone’s head for no good reason. And the title here supports that. Wyeth wants us to see the scene as Christina.

Edvard Munch used it too, in The Lonely Ones:

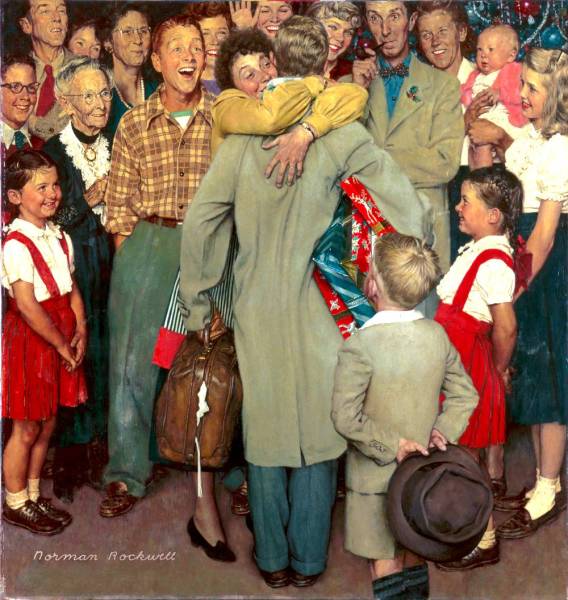

Lest you think it’s only a moody expressionist trick, here’s good old Norman Rockwell:

Realizing that this is not only a named artistic device, but hearing the calculated reason for using it made me realize that Rückenfigur comes up in my work in book covers quite a lot. Because very often in book covers we are trying to get the viewer to self-insert into the character on the cover. And the easiest trick to do that is to not show a character’s face. And if you pay attention to book covers you’ll notice that there’s a number of tropes related to this, especially in genre fiction: Romance, Thrillers, and Fantasy most of all.

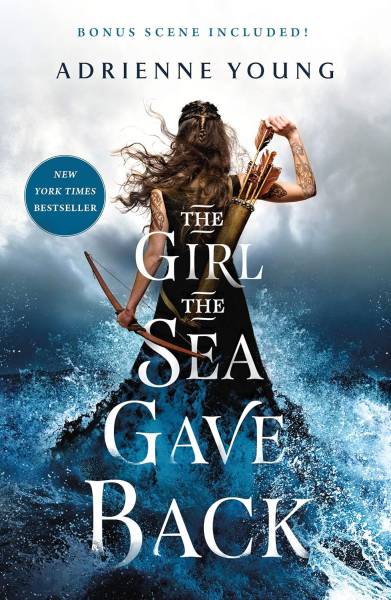

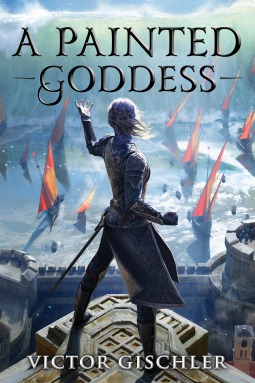

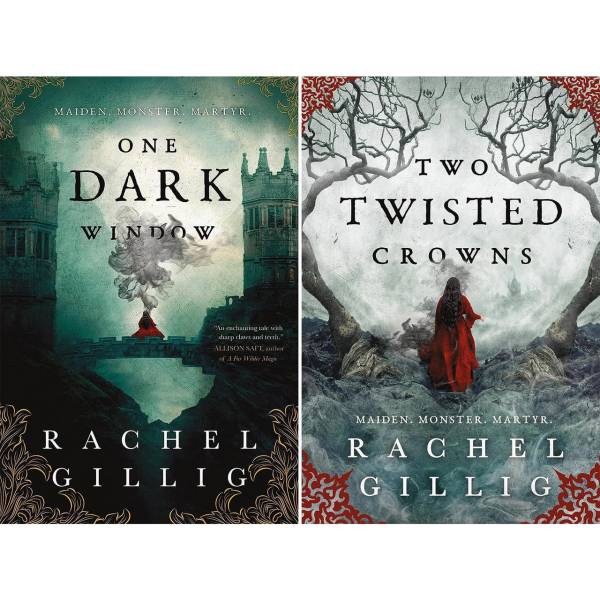

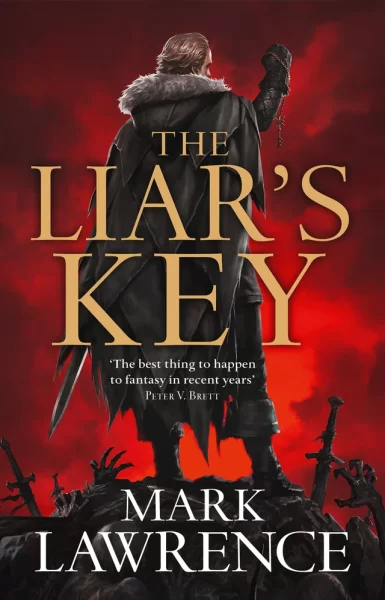

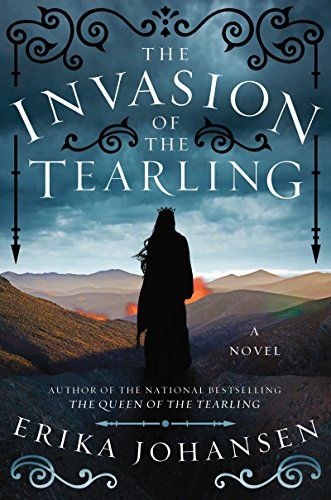

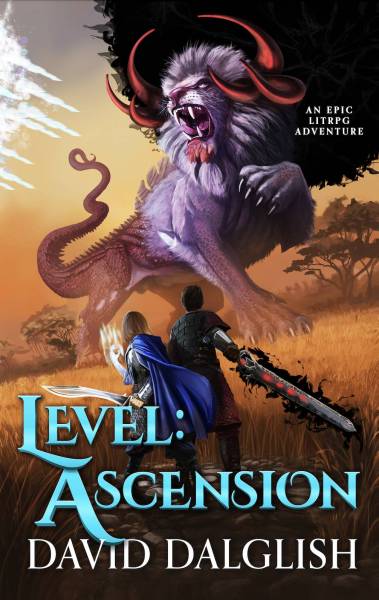

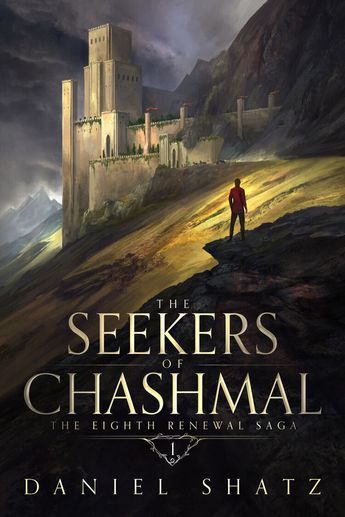

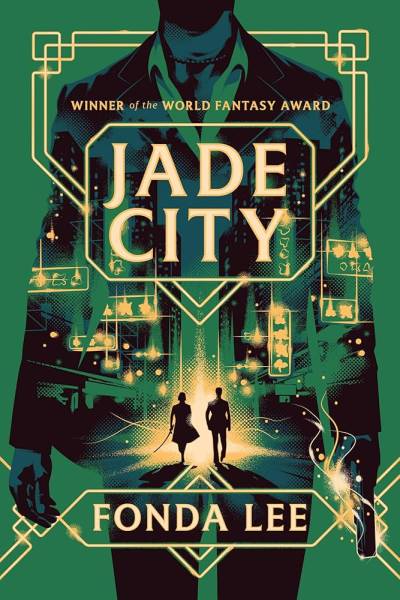

There’s a LOT of pure Rückenfigur:

Would Thrillers even exist if you didn’t have a woman in red walking away from you? Or a silhouetted man running into the distance? Some artists literally do only that (and get paid very well for it. I know, because I have paid them to do it.)

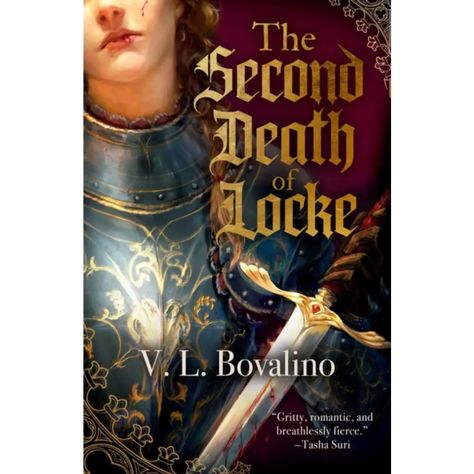

Then there’s the “crop the face right below the eyes” trick, which does the same thing:

There’s a sideways cropping variant of these as well:

And you can also use the “cover the eyes” or “cover the face” technique:

There’s even a variant where the cover is ripped, ruined, or collaged to cover the eyes or whole face:

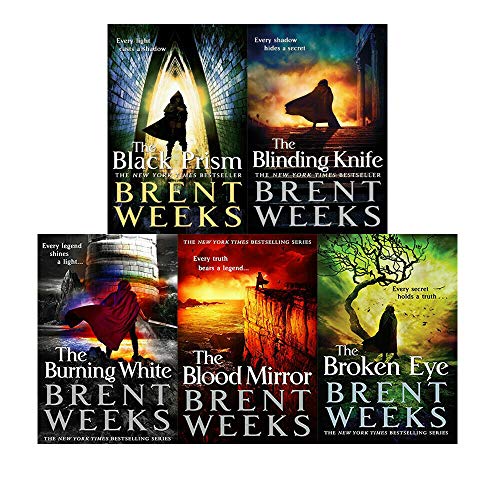

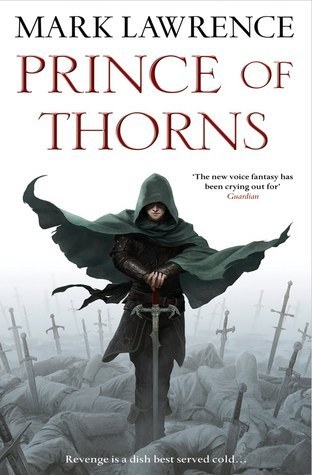

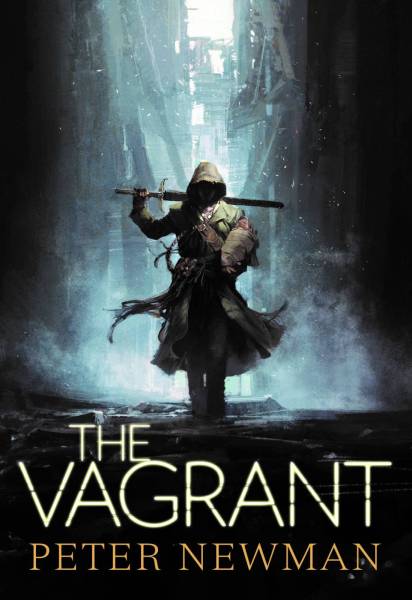

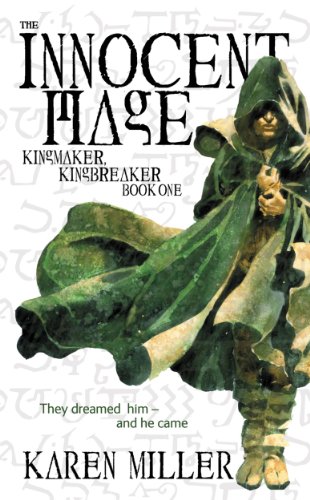

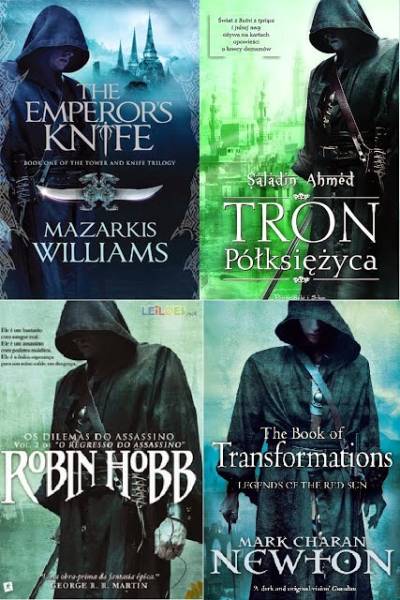

And then there’s the Fantasy specific fave: put them in a hooded cloak that hides their face—known infamously in the SFF biz as the Hooded Man(and occasionally the Hooded Woman):

Sometimes it’s the same hooded man on multiple books:

And special shoutout to this cover I art directed that is a triple threat: Hooded and shadowed, masked, and cropped:

Rückenfigur and the alternative methods we have of obscuring the character’s identity work very effectively to lower the barriers to a viewer self-inserting themselves into the character. And what’s interesting is the studies that have been done (mostly in advertising where they have all the money for market research) show that some groups have more or less trouble with self-insertion. As someone gets older it becomes harder to self-insert because your identity is more formed. You’ll rarely see a face obscured in middle grade kids books, and more on young adult books, but nowhere near as much as adult books. Gender, socioeconomic class, and race play a role as well, for complicated reasons that deserve their own post. And sometimes you have a push-pull going on where obscuring the character helps with self-insertion but representing the character’s age, gender, race, or sexual identity is important so you want to show more of the character. The point is, just like David Friedrich and Andrew Wyeth, when we choose to obscure a character it is a choice with reasons behind it. It’s never random.

And now that you know what to look for, the next time you go into a bookstore, you’ll see how much of the bookcovers you see are using one of these tricks on you. And we’ll keep using them because they work. And if you’re an artist working in book covers, it’ll help to understand what we’re trying to achieve with these covers, and be able to provide your interesting takes on compositions that will help us achieve that Rükenfigur goal.

I did not know neither there was a name for this kind of pictures, nice find Lauren!

I am only missing Dali’s “Girls watching through the window” which is the first picture that comes to my mind when I think of this style.

Oh good one!

What a shame that the comments are so overtaken by spam these days. I came here to study this post more carefully, and it is amazing – this is some of the most mind-opening information on book cover painting composition that I’ve come across in recent years! Thank you so much, Lauren! I just hope the messages of appreciation don’t get lost in the spam 🙂

Thanks Kat! We’re switching to moderated comments — comments will show up more slowly, but at least it won’t be all spam!

Awesome content—very engaging!

The primary strength of the Manav Sampada UP system is the complete digitization of employee service records, including promotions and transfers, which ensures transparency and easy access to an employee’s professional history. This paperless process significantly reduces reliance on manual file management across all state departments.