A few weeks ago Jon Foster and I gave an on-line lecture about the history of Spectrum at The Illustration Academy followed by a series of reviews of portfolios that had been submitted for consideration in advance by members of the audience. I generally don’t like to do portfolio reviews for the simple reason that I don’t view them the same way an educator does. A teacher or mentor offers critiques to help an artist improve and hopefully move on to the next level. As an art director looking at someone’s book my position is less nurturing and more black and white: would I hire this person or wouldn’t I?

Maybe that’s a little cold—I know many art directors who happily offer critiques and suggestions to developing artists in the hopes it will help them achieve their potential—but I try to be a realist. I’ve said elsewhere that artists wanting tips and criticism should show their folios to educators they respect or artists they admire, but they should show their best work to art directors because they’re confident in their abilities and want work. You can only make a good first impression once and the first impression you want an art director to have of you and your art is “too good to pass up.”

So I was a little uncomfortable to do portfolio reviews and promised to let Jon and John English do most of the “heavy lifting.” It went fine. There was a nice mix and the art ranged from good to outstanding: I didn’t have to do much more than say, “I like it,” which suited me fine.

But there was one student folio that was particularly impressive which included mixed media works, beautiful pieces that featured photographs that were digitally manipulated and then painted into and over with traditional methods. Great stuff that was ready for Prime Time as far as I was concerned. One of his instructors at The Illustration Academy, Vanessa Lemen, was also on-line and mentioned that the young artist had been getting criticized when his work had appeared in several exhibits recently because of his methodology. “Even though he’s doing all the work, hiring models, shooting the photos, doing the digital manipulation, and the final painting, some call what he does ‘cheating.'” Vanessa was noticeably frustrated that a young artist was being hammered, not for the quality of his work, but because of the way he chose to create it.

I had an immediate response: “There is no such thing as ‘cheating’ in art.”

No, don’t chime in with exceptions: I’m not talking about plagiarism or anything like that. I was talking about methodology. There is no “right way” to create art; there is no methodology that is blessed, no single path. There is no style or medium or approach that makes one type of art “better” than another. Regardless of those who feel otherwise, art is art.

I don’t care how it’s created: I only care about the results. You’d think that’s all anyone should care about, but unfortunately that’s not the case.

I know of an excellent artist whose works have been disparaged because he shoots photos, transfers them to canvas, then paints over them in oil. I know digital artists who will create an image in Photoshop or Painter, print it out on watercolor paper, then, like the previous artist, paint over it to produce an original. And, of course, when it comes to reference, artists like Maxfield Parrish and Norman Rockwell set up elaborate photo shoots with props and models to help them create their art: none of it simply sprang straight out of their imaginations and onto their easels.

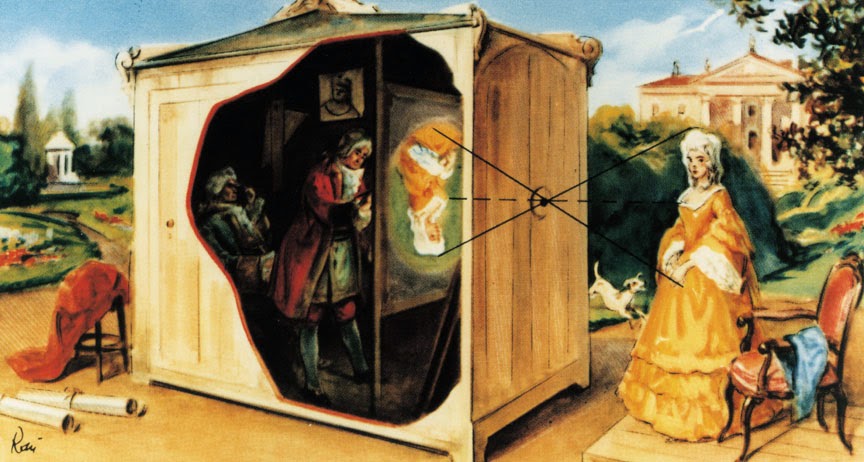

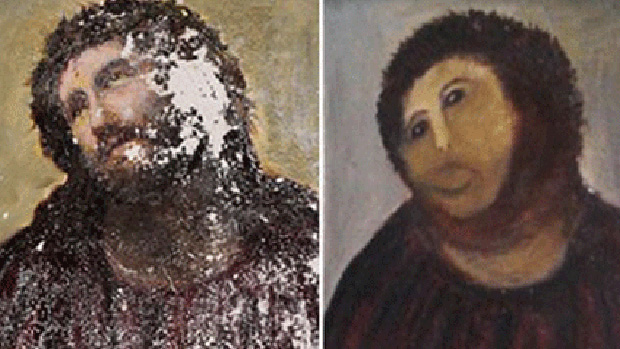

I’ve watched people marvel over the art until someone mentions the technique or methodology, then the attitude changes, the admiration shifts to dismissal, the smile turns into a sneer. It’s no longer “special” because it suddenly seems like a dirty trick. If the art wasn’t magically conjured out of thin air…well! In 2001 the Hockney-Falco thesis was posited in Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters and it ignited a firestorm of controversy from those who thought David Hockney was suggesting that van Eyck, Vermeer, and other Renaissance painters had somehow “cheated” by using a camera obscura. A similar, though less heated (probably because arguing with producers Penn & Teller would not turn out well), controversy surrounded the release of the film Tim’s Vermeer which explored the same territory.

But…cheated? Why? How? And…really, what does it matter?

What is the difference between transferring a pencil drawing to a canvas to use as a guide to paint over and doing the same thing with a drawing created on a screen? What’s the difference between painting from a photo and painting from life?

There isn’t any.

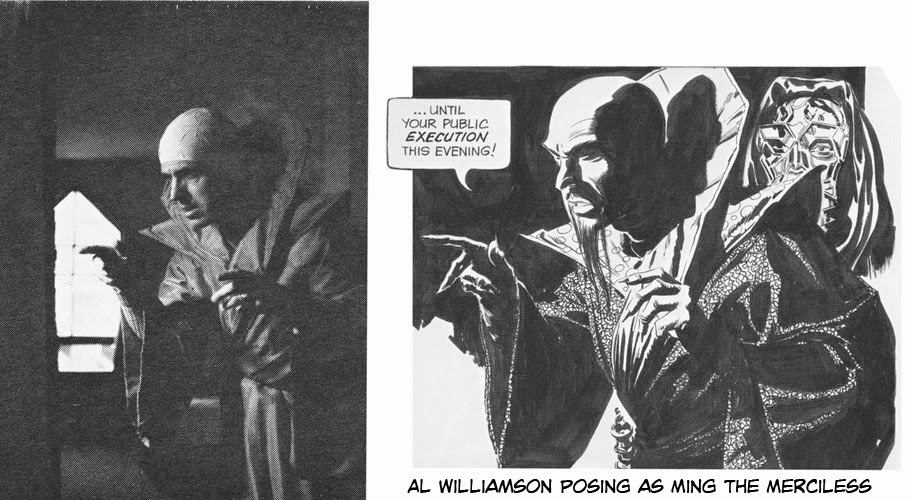

Frank Frazetta would routinely insist that he “made everything up” and never used references or even did roughs: he would chide his friends like Wally Wood and Al Williamson, who kept extensive resource files, used models, and shot photos as part of their creative process. David Winiewicz recently posted an excerpt of an interview he did with Frank in which Fritz insisted he never used himself as a model despite the ample evidence to the contrary. “Of course he did,” Dave told me. That Frank used himself as a model and then denied it were both reflections of his ego (and were also an aspect of the myth that aided in his marketing). As an athlete with movie-star good looks he was an excellent model for his heroes, he just didn’t want to admit that he thought so. Frazetta’s claims over the years added to the cult of personality that surrounded him and allowed the gullible to disparage other illustrators who didn’t “make all it up” or used models or photo reference. But the simple fact was that, regardless of his prodigious drawing skills and an enviable memory which allowed him to approximate things he’d seen almost at will…

Frank used reference.

He shot photos of himself with a camera timer and his wife Ellie in various poses (mostly for lighting: Ellie was petite and not curvaceous like the women he painted), owned and used an oversized Artograph that allowed him to project and trace his reference or comps onto his board, occasionally copied the art of others or swiped photos of models or actors that he’d find in magazines, and created multiple roughs and thumbnails for virtually everything he drew and painted. (Cathy and I even produced a book of his comps called Rough Work.)

While that might cause cries of anguish among the true believers, it does not diminish Frank Frazetta’s art in the slightest. Just as Jan van Eyck or Johannes Vermeer using a camera obscura (if they did) does not make “The Amolfini Portrait” or “Girl with a Pearl Earring” any less the masterpieces they are.

Whatever tool is employed, whatever medium or technique, doesn’t matter: what does, as I have repeatedly said (to the consternation of some), is the intellect behind the tool.

I love Wally Wood’s quote: “Never draw what you can copy; never copy what you can trace; never trace what you can cut out and paste up.” Now, of course, Wood could draw wonderfully and he almost certainly said this in a semi-joking manner. And these days, “copying” (or “swiping” as the comics artists and illustrators of a certain era called it) is a big no-no, but I appreciate that Wally, as a commercial artist from the 1950s till his death in 1981, was more concerned with delivering the job than he was about his technique.

Just as I love Greg Manchess’ much more recent comment during his talk at the reception for his show at the Society of Illustrators last year: he explained that for one of his jobs he had traced the reference he’d been provided for an assignment. The students in the audience audibly gasped, which made Greg laugh, “Time to get real. If you’re going to paint a bottle of Jameson you don’t have to distill the whiskey and blow the glass yourself in order to be authentic.”

I’ve addressed this in the past (most notably in my “Labels” post), but I think it’s worth repeating: for an artist the “how” and “what” are much less important than the results and for people to get hung up on anything else is silly.

So cheating? When it comes to technique or tool or methodology…there ain’t no such thing.

Hooray! This best kept secret has been outed. However … I still do not tell the clients.

Heya, thanks for this post. Do you remember the name of this mixed media artist?

Thanks and greetings

I don't. But I was told that he had something accepted for Spectrum 21 so I'm looking forward to getting better acquainted with his work when the book comes out.

Terrific post! The result is the thing, the process is whatever it takes. Thanks.

I think the only pitfall to such wide-ranging working methods is when you start to believe that YOU drew the thing you traced (as part of a larger project). It's when your ego loses sight of the fact that you actually cleverly cobbled something up. Or if you approach it with a spirit of misrepresentation. I always tell aspiring artists that any method you use is OK as long as you are prepared to reveal your sources if asked, explain your method if asked, and that you have the will to always do better, to NOT just rest on using the same methods/sources all the time. In other words, DO take some time out of your busy schedule and try to learn to draw, not because it's “correct,” but because one day your vision MAY move past your available reference sources and you just may need to know how to draw something you don't have a direct reference for.

But, I agree with Lorna: it's kind of like a magician's code. Be prepared to explain your working methods if asked, but there's no reason to tell all up front. 🙂

Drawing is the heart of all art: if you can't draw, a tracing will look like a tracing, not a drawing. The same with painting: if you can't paint, trying to paint-by-numbers over reference will not fool anyone. Many people are suspicious of digital art because they think the computer does the work: scan a photo, apply an art filter, press a button, and presto you have art. Wrong. Of course there's much more to it than that. In order for an artist to create anything that resonates, they have to understand…everything. Composition, design, color, perspective, anatomy, light, weight, balance, in other words, the whole McGill. A pencil or brush or Wacom tablet aren't magic: without a thorough understanding of the fundamentals, the tool is useless. No different with sculpting, no different with photography. I love Ansel Adams' quote, “You don't take a photograph, you make it.” I think that applies to all art, no matter the methodology employed.

I've never posted here, but I love and enjoy reading these great articles and insights. This blog entry has broken my silence. Every word is spot on & eloquently said, Mr. Fenner.

I too was at the Greg Manchess opening night, I was shocked at that response, that somehow Greg Manchess' art is “less special” because he projected an image. The collective moan from the large audience of students has me concerned for their education. Who is teaching this opinion? That some how there is a worthy and not worthy method of picture making. In their studies, they should be trying every method, tracing, gridding, opaque projecting and the many more. Each should be celebrated. Each should be explained and taught for its merits and its pitfalls. That new method of practice could be the thing that takes a young artist from student to professional.

One question. If an artist is very close to being ready for professional work, do you think your art directors eye could lead them in the right direction? Thanks!

I don't know whether my eye would lead an artist in the right direction or off the ledge of a cliff. 🙂 I think I know what makes a good cover and can probably provide some suggestions to help tweak a piece here and there. But the caveat I always give is that any direction is subjective: what I may be looking for may be the opposite of what another art director needs or likes. I always suggest researching the market, making special note of what jumps out at you, and then analyzing the reason why. Not with the intent of replicating what's already been done, but to understand what “works” then developing solutions that are fresh yet fulfill the same function.

Is it cheating that I let my pug paint for me? She is gifted. I've found everything is about lines we make in the sand. In our minds crossing that line is a bad thing. Groups make lines. Some watercolor societies will not look at work that has even a dot of opaque paint. Some ateliers will shun anything not done from life. Laws are like that. We can let groups make lines for us by joining but we cannot and should not make lines for other people. We can choose not to like someone's work but their methods are their own. If you do come to Boise State however, all lines are mine.

AMEN. Bill Sanchez, one of my favorite instructors at the AAU in San Francisco, beat this into all of us. He showed us tons of his work where he cut, pasted, traced, he even cut out some wallpaper and pasted it on an illo for a magazine because painting all the individual flowers would have blown the deadline.

And Bill, my son occasionally “helps” me paint. Sometimes without telling me. Always a fun ride.

Hello Matthias, it was me. You can see my work in: http://samuelaraya.weebly.com/

(I should add, for the sake of transparency that I also use stock and copyright free photos from time to time.)

Thank you for the porftolio review, Arnie!

I would however add, that Im not that young at all 😉

But seriously, I can´t thank you enough, I keep the “There is no such thing as 'cheating' in art.” as my mantra. I can say with all sincerity, that a 2 hour class certainly changed my life, all for the better!

A little while ago I made a comic about how people think digital painting works, that it's a kind of cheating because the computer does the work for you: http://kmcmorris.blogspot.com/2014/04/how-people-think-digital-painting-works.html

Just go see “Tim's Vermeer”, http://sonyclassics.com/timsvermeer/. It is amazing and covers what may possibly be the method Vermeer used to create his paintings which uses a bit more than a camera obscura. Jaw dropping and a total “cheat”.

I didn't read David Hockney's book, but from what I understand, the controversy isn't that he said artists used the camera obscura, but that he suggested they were not skilled enough to draw realistically without it.

I used to believe Frazetta didn't draw without reference. Now I know better, but there was a time when I felt bad that I couldn't do what he did, presumably out of his head. I have the book Rough Work by the way, and it's great.

I had seen Hockney on 60 Minutes years ago (if I recall correctly) talking about it and I don't remember that he diminished the skills of the Masters but was merely talking about how they managed to do what they did. My memory could be playing me false.

Frank was a wonderful cartoonist and used that ability to exaggerate and make something feel both familiar and “right.” He was such a powerful dramatist that he could get away with stuff other artists would be lambasted for. I'm not sure how or when the whole “making it all up” story got started; Dr. Dave might know, but it seemed to have got cooking in the late 1970s. Up until then, I doubt that Frank really cared what people thought, but after the Esquire article and American Artist profile and following the appearance of a lot of younger competitors I think he and Ellie decided it might be a way to maintain his position. He didn't need to. Frazetta was always Frazetta. 🙂

This is great timing for me. I recently had 2 experiences where I was pretty much dropped from a competition and told later by an art director that I essentially cheated by painting over photos. Well one, I didn't paint over them I collected my reference using my wife and I as the main characters and then yes, traced out the main poses to save time and added different costumes and details (unless you want to believe my wife really is a Valkyrie). I was wanting to do something photo real since this is what I like and to test my skill. I spent a good amount of time on the piece and got a result I was happy with but I think because it is digital everyone assumes I didn't take the time to actually do the work. Far, far from it. Funny thing was I laid out the process in the competition which you can see here http://ryanarmsart.blogspot.com/2014/03/illustration-workflow.html and they still insisted I was cheating. So, thank you for showing me the lessons I learned sometime ago and recently again are valid.

This is really an interesting post, especially for many digital painter out there to think about and gather more self-awareness about their actual skills. I think many people (not only artists) clinge to methodology. I have a traditional airbrush background -most airbrush images depend on photographs and tracing. On conventions – (also airbrush- conventions) people see me draw on my tablet and instantly get in a contact with questions regarding the techniques – there is no devaluation, neither from artists nor visitors. Quite recently a hobbyist told me that many pull their ideas and inspiration from us digital artists – that was quite a honor. I quit airbrushing because it would not allow me to develop ideas as flexible as working with a computer does. I think tracing for the sake of acuracy is not cheating, but not questioning reference iamges is silly. Because after all, tracing bears always the danger of copying existing flaws – and nobody wants that.

What counts is the result – in my book everyone discussing technique in an nonconstructive manner is a troll and not worth wasting time with.

The real cheating in art, and that is only my humble opinion, is to use existing things, putting them in a museum, call them “ready-mades” and sell it as art, but that – is a totally different story:)

Thank you for sharing valuable information. Nice post. I enjoyed reading this post. The whole blog is very nice found some good stuff and good information here Thanks..Also visit my page Entrepreneurship If you want to win in life or poker, you must take risks and weigh out the odds of winning and losing.

Not that young? Then, Sam, I expect to see a whole lot of kickass art by you appearing all over the place pronto! 🙂

Very nice article, I think we all think that well known artists create their images out of thin air. I guess certain circumstances require or are better solved with easier approaches. Kind of reminds me of popular singers who don't write their own music 99.9% of the time yet the community knows this and are okay with it. I always like the White Knight approach of doing things, pretty much the hard way. But art is all over the place, I rarely use reference. I think I traced when I was child or if that, just seems weird and wrong. I guess when an artist needs to pump out projects quickly to get a buck, like the article says in a nutshell, “anything goes”.

When it comes to the physical result of the work there is no cheating, but when it comes to the other great benefit of art – the inner work, or the possibly transformative/mental result , there is. Depending on how you work with art you will get different results in the development of visualization, imagination, patience, understanding of color, light etc, and perhaps most important of all… self knowledge.

If it feels like cheating, it could be some part of you reconizes, that doing it 'this way' makes you miss out on something valuable…. or you simply have a too finely tuned conscience. 😉

As a matter of routine artists have self-doubt or insecurities and question their solutions: do they measure up to those they admire? Are they doing it “right?” It's all part of the journey. But I believe the concept of “cheating” in art almost invariably is an opinion held or expressed by the watchers, not the doers. The loudest critics of process or methodology are usually the ones who know the least (and rarely—if ever—are capable of creating the art they either extol or disparage).

“if you can't draw, a tracing will look like a tracing, not a drawing.” Hit the nail on the head.

Excellent article. I totally agree that there is no cheating in art. Eakins, Zorn, Sargent, Bougereau, all used photos. However I disagree with the Hockney hypothesis, not because I think it would be cheating, but because there is no evidence that they used the camera lucida or convex mirror in that way. We have tons of evidence that they used grids, screens, all kinds of aids, but nothing on the camera obscura, lucida or convex mirror. You would have to believe that they were entirely upfront about everything else they were doing, but somehow managed to keep this secret, which is why Hockney called his book “secret knowledge” but it's impossible to imagine how artists maintained a 300 year old conspiracy of silence over all of Europe. Great theory, it just doesn't hold up.

Haha! Loved that cartoon. Thanks for sharing!l

Thank you for writing this. I'm three years into my first full time illustration job, within an environment that has no illustration mentorship. I struggle a lot with the available digital tools, alongside time constraints, deadlines, and quality of work. I've never stolen another artist work, but I have used every tool available to deliver on time and rendered to the quality needed by my employer.

This is very true. Unfortunately the watchers opinions are often so loud they start to make the doers question their own methods.

Fantastic post! I agree with you Arnie that there is no such thing as “cheating” when it comes to one's process however I do believe that one's process can potentially cheat one out of doing their best work. Much like Nicholas says above, sometimes a certain process can become a crutch in which it behooves the artist to explore other methods so that they don't miss out on discovering something important to their overall growth as an artist. Like you say though, this is all part of the journey, it's just up to the artist to evaluate their own insecurities and solutions without being too heavily influenced by the uninformed watchers of the world. http://maxmartelli.blogspot.com/2014/04/cheating.html

Oh, sure; there's the whole personal philosophical/psychological aspect of being an artist that I think we all struggle with. But speaking strictly from a practical standpoint, shoot, whatever it takes to get the image down, like love & war, seems fair to me. 🙂

Mark, for commercial work, you do whatever works to get the job done, never give it a second thought, and, if done honestly, never feel regrets. For personal work and the method employed, it's a matter of choices and decisions, but only you can make them. Everybody else can either accept or reject them, but they can't dictate what you do. If they try…they're not worth listening to. 🙂

As I said over on Dan's post, thank you for this. I get tired of hearing what I do isn't art just because I chose to make it with the computer instead of with acrylics. Please. A digital artist still needs to understand form, perspective, color theory, etc., to be a good artist. Working on the computer doesn't make that go away.

I wish more people would recognize digital painting as simply another medium rather than as a sort of “cheat code for doing art”, if you will. Because it isn't. As I explained once, You + Computer + Drawing Tablet ≠ Master at Painting. You have to learn and practice as much as any oil or acrylic painter does. I bet you my former art professors, all accomplished traditional artists with not a lick of digital painting experience, couldn't create a decent digital painting their first time out. It takes time to learn the medium, after all, just as it does with other media in art!

I'll never understand disparaging a work based on the WAY it was created. Nonsensical, if you ask me.

I agree that we have to get away from that whole “cheating” thing, but the reason it keeps coming back is that for a lot of folks depicting something convincingly is some sort of magic talent or parlor trick. Despite the fact that we have cameras and other machines that can create very convincing imagery, people are still impressed by the ability to render, and they conflate that *skill* with “art.” It's a bit like being impressed with a gymnast vs. a dancer. It's just very easy to grasp the concrete achievement of realistic rendering, vs. trying to understand and articulate what makes a piece of art strong (especially an “abstract” piece of art). But artists are not free of this either, and this is one reason why we still need to beware of using photos. Many artists still don't understand the difference between *realistic* and *photographic*. And many are still more concerned with the individual elements of a picture looking good vs. the abstract whole being powerful. So even though, yes, it's the result that matters, the result many artists are aiming for is unconsciously influenced by photos. Most of us can tell when we are looking at something that is either closely based on a photo or is literally incorporating one. Even if the artist has amazing composition skills and is creating the photos him/herself, we see immediately that part of the image is not the artist's hand, and feels alien. This often undermines the cohesiveness and strength of the image, even for those of us who absolutely do not view this as “cheating.” So for the general public, for what it's worth, sure, the message should be that there is no such thing as “cheating”, but for artists I think the message should be “learn to see photographs for what they are, THEN decide if/how you want to use them.” I think photos still represent a bigger pitfall to artists than the fear of being labelled a cheater.

From my perspective I think it boils down to simply the skill sets of the artists and how well they use their references. I agree that learning how to “see” is paramount for an artist but consider photos as something of a fall guy, not the culprit. To me, there's no difference between painting from a live model than there is from painting from a photo (and I've done both). I have seen more than my share of life drawings and plain air paintings and just as many “made up” pieces that are, honestly, terrible (and have done my share). Those failures aren't the fault of either the tool or the reference, just as the successes aren't either. Regardless of how it was created, whatever results, good or bad, is because of the artist's use of the tool and interpretation of the reference.

Damn auto spellcheck! PLEIN air. Yesh.

I painted portraits in college, and I'd spend hours and hours doing preliminary drawings to get the proportions right before I started painting. I was successful enough that everyone in my class assumed I had used a projector. The projector/tracing comments happened so often that by junior year I finally realized: why the hell am I wasting my time drawing when everyone assumes I traced it anyway? That was like 10 years ago, and I have been projecting and tracing ever since. My situation is a little different since the end object is still an oil painting, but if no one can tell the difference (and people are assuming I projected anyway), then who cares? Why would I spend hours painstakingly measuring proportions if my particular end result is going to look exactly the same?

Good article.

It's true that in art, results are all that matter–“if it looks right, it's right”. I feel compelled to dispute a common misunderstanding that you repeat in your article, though;

< What's the difference between painting from a photo and painting from life? There isn't any. >

There is a world of difference and an experienced eye can always spot it in an artist's work. When working from life the information being viewed is shifting over time, especially in the case of a model, who cannot remain entirely motionless. The artist is also moving, however slightly, and seeing with two eyes, thus in three dimensions, causing the orientation of all the shape relationships to shift each time the artist moves his /her eyes to focus on a different section. The most important difference is the natural selectivity and discrimination that is a function of human sight–the attention is focused on a particular point of interest at each moment, and the material around it is subdued, even slightly blurred.

All this combines during the drawing/painting process to create an entirely different sense of depth, volume, weight and space, which adds an organic natural beauty, force and subtlety to artwork made through real world observation by a skilled mind and hand. A photograph is a flat pattern of shapes that have been indiscriminately recorded by a mechanical lens– two dimensional, airless and weightless. For a serious draftsman, the rich experience of drawing from life bears little resemblance to the functional construction procedure of working from a photograph.

Photographs are a legitimate, and for many subjects, indispensable tool for making artwork, no argument there–I'm not criticizing them or their use at all, but I think it's important to acknowledge their very real and severe limitations. Most of the problems art students have is rooted in a basic inability to see–to correctly observe space and relationships in depth. Accurate drawing or painting depends on accurate perception, not rendering skill, and photographs are a dangerous and limiting crutch if a young artist depends on them too heavily before learning to see with their own eyes first.

I'm actually a strong advocate of using photos, and have had my fair share of failures with the full range of processes, methods and tools…

But at the same time Blev is right – as human beings in the real physical world, we engage with a real physical person and environment differently from how we engage with a photo, and it's not just the eyes that are involved in observation and picture making.

But I think the main point of the original “Cheating” post was that we need to dispense with this stigma associated with using photos. The problem is we can't seem to make the point that there are specific issues with using photos (just as there are in many cases with NOT using them), without that triggering a simple defense of the legitimacy of the practice.

I think Chris’ 4/23 post hits many of the points I thought of when I read your article. Let me just add my two cents.

Yes, artists don’t work in a vacuum. To work realistically you must at some point use reference to “check your work”. But, as I was taught in art history: “photographs lie.” No photograph replicates the item being photographed. It's a flattened, distorted image with lens artifacts, lighting issues, and anatomy that often looks plain wrong in comparison to the real thing.

That's my issue with painting or photo montaging directly over photos. You’re stuck with all their inherent flaws. Art made from photos has a very flat, unreal look to me. Why would you *want* to work over a flawed underlay? There's a reason art students draw directly from the model. If photographs conveyed form 100% accurately, live figure models would be out of work…

When Photoshop first came out (yes, I've used it since ver 1.0) a slew of bad work was masqueraded as “art”. Suddenly anyone could take photos, jam them together, and call it art. I’ll admit I made me think all digital art was bad. This is also probably why the “digital art isn't real art” view persists. BUT digital tools made leaps and bounds since then, to point where you can “paint” some incredible digital art.

Then why do poor photomanips still exist in the market?!? They’re cheaper to make and buy. That doesn’t make them good art. Take one glance across the scifi/fantasy shelves of any book store for an endless parade of poorly-montaged “cover art”. This is esp. ironic on steampunk books; the movement (not literary genre) came as a response to the plastic, injection-molded look of modern tech.

I can still tell art created over a photograph vs. used as reference. *Still* And it's been almost 30 years of digital art since… Why? The work is often formulaic. Like the Frazetta spawning the cookie-cutter barbarian fantasy art genre, photo montaged work can be just as formulaic. Take several photos, add background elements, darken details at the edges to soften hard lines where photos meet, and add filtering or “stuff” flying/floating around in the background to make it feel like there's a scene.

Norman Rockwell is often mentioned as the poster child for detailed, posed reference photos. However, he painter’s eye and talent made the result more than a sum of its parts. A Rockwell painting imbues a spirit you can't just capture if the same photos were glued on a canvas and doctored up. His use of color and form sends the message he wants you to see. For reference on Rockwell’s method: http://muddycolors.blogspot.com/2014/04/process-to-people-part-1.html

Yes, many great illustrators used photo reference, but they didn't become slaves to it.

Cursed Blogger character limits… Here's part two of my comment:

I worry that generations of artists will assume there’s no difference between *referring* to a photo and working directly over it. If that were so, all the classic illustrators would have done it. Think modern illustrators have deadlines? Look up pulp artists: Norman Saunders alone created roughly *300* oil paintings in the 30s-40s…

Let me use another recent example that shows my point (part two by Howard Lynch):

http://muddycolors.blogspot.com/2014/04/process-to-people-part-2.html

I was floored that he fully rendered it digitally before painting it in oil… Seems like a lot of work to redo it, even using the digital color comp. And I liked the digital version (in some ways more than the oil, due to my love of detail.) But looking at the two images side-by-side, the oil painting looks better – not because of the medium. In retrospect it was obvious he used the photo directly in the digital comp, and took (d'oh!) artistic license with the oil painting.

The oil painting used his artist's eye. He widened her face and illuminated it by adding a subtle diagonal light across the piece. This heightened the spiritual feeling. He made artistic decisions that simply might not be possible if he stuck slavishly to the photo. The end result is a better synergy and a stronger piece.

Blev – couldn't agree more!

Blev—Your view falls into the philosophical/psychological aspect of being an artist. “Feeling.” “Seeing.” “Engaging.” All fine and good. They're personal perspectives or opinions (your “experienced eye” comment made me grin) that of course don't necessarily translate into the same things for everyone or a good piece of art. Whether painting from life or painting from photos, the crud and gold in both camps are legion. But of course I was talking strictly brass tacks practicality using my own experience as an example: you don't have to agree, just as I don't have to agree with you. Call me a Philistine, but at the end of the day I don't care one iota if you “feel” the piece when you created it and I don't care how you achieved it, I only care about the results (as I said earlier).

Chris—Yes, that was my main point: to dispense with the stigma that there's a “wrong way” to produce art, that one way is evil and another is anointed. A debate over the use or non-use of photo references is entirely off-track. Interesting, but something else entirely.

But the question is, if he ultimately achieved “a better synergy and a stronger piece”…what's wrong with that? He got there. Isn't that all that matters? For me, it is.

This is a fabulous discussion by all parties from an equally wonderful post! Couple of my thoughts here, especially for painters.

Photography is not a copy of life, or reality. Photography is a technical medium for capturing light across a moment in time.

Paintings are completely and utterly different. Get this clear: a painting is not a poor excuse for a lack of photography. In other words, just because I didn't have a camera when I encountered that figure in my head is not a reason for why I shouldn't paint it. Or use photography to bring the realistic vision out.

I LOVE photography. I am INFLUENCED BY PHOTOGRAPHY. I use photography to help me express the pictures I want to show. I COPY photos in that process. I love the effects that photos bring to the idea of light, and the idea of reality….and most importantly, what it can tell me about completing the illusion of dimensional space on a two dimensional picture plane. But it is not the end result.

Michaelangelo, DiVinci…all of them would've made use of a camera if they had the tech. This is not about doing it correctly. Painting is about doing it well.

We trip over the idea that if we were good enough painters we would all be doing paintings that look like photographs. You and I both know this is not true. We also know from the history of art that many, many painters could care less about this.

I also teach that tracing is a brilliant learning tool. I can get students to know anatomy much faster by coaching them through tracing. Your brain feels the lines and records these motions so that when drawing the next time, one relies on this training. Ah, heck…there's not enough room here to talk about this. I'd love to answer about Frazetta, Rockwell, and others…(love those guys…)

Anyway, this post is fabulous as it strikes the core of many of the problems artists must overcome. Great reply Blev….like that explanation. Elizabeth R: nice answer!

Cheating is a silly concept. Talent is for sissies. And remember:

Do whatever it takes to get the image to the surface.

Painting is not about photography. It never will be.

And TF….I LOVE digital paintings. You are still painting when you paint digitally (just too bad there's no original). But you gotta stop hanging around folks that do not understand this.

C'mon over here and hang with all of us on Muddy. We embrace it all here. You would do well to only allow yourself to discuss your artwork with those that will support it, at least for now.

You'll gain better confidence, if you do that, as you go along and get better.

Lastly, no one will ever really understand you, except other painters and those that support it.

I'm always glad to inspire a grin, and obviously there is no requirement to agree.

You seemed to have missed or sidestepped my point though–the words “feeling”, “engaging”, or other vague terms that attempt to describe a “philosophical/psychological” concept are never mentioned or implied in my comment–I described only the factual distinction between physical observation of life and the more limited/distorted information that can be captured by a camera lens, used as sources for making artwork. The subject of “feeling” in a piece of artwork is an entirely different conversation that has nothing to do with my objection to your “strictly brass tacks” declaration that there is no difference between working from life or from photographs.

That is my point–you shouldn't make an authoritative statement that isn't true. You personally may experience no difference, but that doesn't define the experience as a universal fact.

There is nothing wrong with working from photos, there is no “cheating” issue–but photographs do not replicate observation, especially in instances such as foreshortening. An accomplished realist artist also knows how important the perception of edges, and the translation of them into drawn marks or brush strokes, are in creating a convincing illusion of depth and space. Photos rarely reflect the eye's perception of edges, unless filters are used to attempt a mechanical simulation.

I feel strongly about this point because it is such a common struggle for young artists to understand the importance of their own two-eyed vision. If they are happy working entirely within the scope of what a camera lens can record, fine–but if they want to achieve the energy or atmospheric effects of artists such as Jack Kirby, Frazetta, Rembrandt or Rockwell they have to enhance their photo reference with knowledge only found in real world observation. It's hard enough to learn how to make good artwork without the stumbling blocks of inaccurate information.

“I can still tell art created over a photograph vs. used as reference. *Still* And it's been almost 30 years of digital art since… Why?”

Because you're looking at bad art created over a photograph. I betcha I could point you to some that work wonderfully and you'd never know (at least in my opinion)… 🙂

“You seemed to have missed or sidestepped my point though–the words “feeling”, “engaging”, or other vague terms that attempt to describe a “philosophical/psychological” concept are never mentioned or implied in my comment–I described only the factual distinction between physical observation of life and the more limited/distorted information that can be captured by a camera lens, used as sources for making artwork. The subject of “feeling” in a piece of artwork is an entirely different conversation that has nothing to do with my objection to your “strictly brass tacks” declaration that there is no difference between working from life or from photographs.”

I don't think I've missed your point or sidestepped an issue, I simply don't think we view things the same way. When you say “Most of the problems art students have is rooted in a basic inability to see–to correctly observe space and relationships in depth” that's painting a pretty big picture with a pretty broad brush. How do you know what an student sees? How do you know what they think or perceive? You can't. You can judge their failures and guess at the reasons, but…only they know what they “see.” Or don't see. That's where your “facts” tip over to philosophy, psychology, opinion, and belief structure.

“That is my point–you shouldn't make an authoritative statement that isn't true. You personally may experience no difference, but that doesn't define the experience as a universal fact. “

For YOU, Blev. Again, you are expressing a personal view (definitely making your own authoritative statement, as it were) that you believe strongly in—just as I am (though we are, I think, really talking about different things). I am, despite any side topics, trying to stay focused on the concept of considering a methodology in art as “cheating.” I don't think any method is cheating. Period.

I have never said at any point that I believe that painting or drawing from a photo is superior to drawing from life—or vice versa—only that, after a lengthy career on both sides of the table, as long as an artwork succeeds, I don't see any difference. And really all I HAVE said is that it's what the artist does with the tools at hand, including their reference—which can either be a live model in the studio or a photo of one—that matters. For every successful artwork painted from life you might trot out, I can show you a failure. For every painting you might offer which relied only on photo reference that falls flat (lacks “depth” or fails to “replicate observation,” as you say), I can trot out one that succeeds beyond anyone's wildest expectations. What's the point? To say that there are artists that use their tools and resources and skills well and others who don't?

I thought we already had.

So, we agree about some stuff (there is no “cheating”) and disagree about others. That's okay with me. 🙂

That's okay with me, too. We don't share a definition of terms, so it's pointless to talk past each other.

This last comment is attempt to clarify that I was speaking entirely in concrete terms–my use of the the term “seeing” means exactly that–the clear simple accurate grasp of what the eye is looking at. Your vague semantic misdirection about “not knowing what a student thinks or perceives” has nothing to do with what I'm discussing, which is the basic skill of learning to accurately make drawings or paintings of what the artist is looking at–from life or photos. If a student is struggling to place features symmetrically on a face or draw limbs of matching length, they are not able to process what their eyes are observing and put it down correctly on paper. They are not seeing accurately.

I've often used the trick of having a student copy a simple line drawing–the attempt for a beginner is usually a poor one, then immediately have them copy it upside down to vastly more accurate results. When the subject matter is removed from their thoughts and the image becomes simple shape relationships, their accuracy of observation almost always improves dramatically, sometimes remarkably–they are seeing as an artist needs to see in order to draw realistically, by observing what they actually SEE with their eyes, and not trying to inject what they already logically “know” or intellectually “perceive” about the subject. That's where most error comes from, this knowledge conflict that is essentially contaminating what the eyes are communicating to the brain.

( If the brain is actually altering the input, as is suspected in the circumstances of El Greco or Van Gogh, that is a special circumstance. I'm referring to normal vision. )

This is not a difficult concept to grasp, and it is not relative for various people, it's a simple physical skill that can be taught and learned. Becoming an accomplished artist and making amazing artwork is a completely different subject, which has to do with a person's inner vision etc.. Once an artist has good command of this skill, the world of creation is open to her/him–exaggeration, distortion, any kind of visual invention is accessible because they are not fighting the simple hurdle of being unable to translate their ideas into visible form.

That's why I think all artists should study and sketch from life before becoming entirely reliant on photo reference–without that observational skill it is very difficult to correct the limitations of source photography.

That's what I said, simply and directly I thought, in my previous posts. Not your interpretation of what you decided I meant, and then responded to. Almost every time I act on the rare impulse to comment on a forum, I regret it, and this is no exception. It seems impossible to stay on task, and clear language doesn't seem to help much. So I leave you to it–I'm off to draw blood from a stone, then make a drawing of the blood, then take a photo of the drawing of the blood, prop it up, and draw the photo from life. Maybe I'll learn something 🙂

That would be nice. Email it to me when you're finished and I'll tell you if I'd hire you or not.

🙂

My take may have seemed off the subject that “photos aren't cheating”, but my point was that's all we seem to be allowed to say about it. I feel that only telling that half of the story is misleading.

It's true enough that if the artist “gets there” that's all that matters – the problem is most artists never get there and don't understand why. For many it's because they reflexively looked to photos, specifically, for answers, and never learn to see the common, recurring and predictable issues with them.

It's funny, again, as someone who worked traditionally for many years and is now 100% digital and very happy with this, I can say that there definitely are specific issues and challenges with working digitally (e.g. the lack of “fear” due to the easy reversibility of decisions makes me at least somewhat less engaged than with physical paint, not to mention the pathetically simplistic mark-making compared to a real brush) – but again, all we ever seem to be able to say on the subject is that digital painting is painting, and digital art is art.

I disagree, Chris: the conversation can, will, and should most definitely continue about the benefits, challenges, or pitfalls of using photo reference (and any other methodology or technique or sensibility)…just in the place (or post, rather) in which that's the topic. I understand how one subject or even a single comment can prompt an entirely different direction for discussion or debate, but the result almost always winds up being a quizzical, “What were we talking about in the first place?” I simply like to try stick with the subject at hand and not veer off into other territory.

Dan may be The Muddy Evil Overlord, but he's always looking for guest posters to Muddy to keep things fresh and lively. Drop him a note if you'd like to write about views or issues you'd like to express or explore. Dan doesn't bite. Hard, anyway…okay, that's a lie. He does. REALLY hard. 🙂

Hah, ok, fair enough Arnie.

Wow, I come back and the discussion always seems to wander. So my neat little tie up would be; if we could all agree that a piece was wonderful, a masterpiece, would it matter how the artist got there? If a piece were wonderful and the method included using photographs we could then agree that the artist knew how to use photographic reference. But the real question will always be, can something be effective and not be good? I mean visually a masterpiece? Do art buyers always buy the best artwork or do they buy the thing that will sell the most of their product? If those photo paint overs, or whatever we choose to call them, are selling books etc. then for the moment they are the most effective illustrations. Illustrators adapt or die. If they have found new ways to use photographic reference maybe it's about survival. And maybe I am just talking out my ass because I din't sleep well last night and should be getting ready for bed.

Wonderful article. I do think there is a logical reason that some people feel painting with a ton of aids is cheating. Say you have one painter creating beautiful realistic works from looking at something and putting the marks down on the canvas. And you have another applying paint directly over a photo. Doesn't the former takes much more time, effort, training and skill? There will always be people in awe of the ability to look at a scene and render it.

I say this as an oil painter who works from photos and often traces some lines for proportion. 'Cause ain't nobody got time sight size everything if they actually want to sell more than a couple paintings a year 🙂

hello guys, I'm Italian, sorry but my english is not so good, but I'll try to tell my opinion about:

I'm an Illustrator (digital also, but first traditional for all life) I've studied all my life since I was 12 years old and I keep study right now to improve my art…digital programs are god tool to help who is a professinal to get quick jobs, more or less like old masters like Caravaggio, that used “camera oscura” …but the point is, that old masters where great artist able to draw and paint for real, study long time,since they where kids to became great artist, you saw in the museums the amazing pencil drawing of William Bouguereau, Antonio Ciseri, Francesco Hayez, Gerome…they where real amazing masters, they knw how to draw and paint, if they used camera oscura was probably just for help to get bigger size on huge canvas, or speed their job,

.right now too many people, specially young guys,wihtout even study in a real school, use computer manipulation tracing, paint digitally over photos, print and paint..extc…without be real pro artist, download free Totutorials from Internet….free (cracked)programs, from all over the world, anybody can do digital art looking cool just manipulate photos without studyng, without feel how hard is to became an artist for real, years of hard work, years of bloody eyes untill 5 in the morning try to improve drawing and paint….

everything it's so easy today, take photo, download a free tutorial, get cool in 1 month…..and then?

too many artist go around the web, in one email sending art over 50 different publishers around the world, (we used to take a flight and go around countryes with a fisical portfolio,with original art,spend lot f money for travel, sleep, meet the Art directors) now with a free email everybody can contact the clients looking for jobs asking 1/4 of the rates that a professional old artist ask to the client!!

THat's the point! is not be or not to be an “artist” or how to make art,…..professional artist, make a living since years, we had some kind of rates who make us living….right now in my country and Europe, many of us (old guys) are having big trouble, because the publishers have so many artist from all over the world,specially coutries where 300 $ are a monthly salary, working for cheap..or for free….doing photo manipulations in photoshop looking like good art covers………do you think this is nto Cheating?

right now many illustrators in Europe and USA are having truble to make a living!

do you see Science fiction books illustrated? Cinema movie posters Illustrated? in Europe are all photos, not even manipulated. 15 years ago was a good job for many Illustrators (like Renato Casaro, Luciano Crovato and more) this job doasn't exist anymore, and few publishers wh still do books illustrated pay ridiculos rates, nobody can live in Europe with this salary! this marke tis destroyed for professional Artist.

it's like “music world”….people go to study in the music academy for 10 years for learn how to became a great musician..and then there are other guys that play music with computer in the mom basement, without learning guitar, drum..or wihtout learn how to sing for real..they use all the tricks to manipulate voice, use a base for drum and guitar….and get jobs!!

everybody is welcome to be artist and make a living, but there should be “rules” in this world…right now, there are no more rules, no more respect, some Art directors don't even understand the difference between a real art and a photomanipulation……they do not even understand how hard is to became an Artist, and how much an art should have been payed!

many publishers just wanna get chep art, thats' all.

this is what happen in the last 15 years, and probably the future is not gonna be better.

thank you for this article Arnie.

Lucio Parrillo

Thanks for your post, Lucio. I understand your frustrations in today's marketplace: they're shared by artists all over the world in all industries. There HAS been a devaluation of art and creativity for a number of reasons, not the least of which are the “free & instant gratification culture” that sprang up with the Internet and the shift from businesses that were independently owned to those owned by giant corporations (ruled by accounting departments and share holders).

But, again, that's another subject entirely: I do not believe any methodology used in the creation of art is “cheating.” One method may become pervasive over another (for a time), but it's popularity or pervasiveness shouldn't make it any less valid than methods that require a different process. Because something “seems” easy to an observer or competitor…doesn't make it easy. Jon Foster's or Stephan Martiniere's or Android Jones' digital paintings are astonishing and require the same sensibility and skills to achieve as someone painting in acrylic or oil; Greg Manchess paints so fluidly and “effortlessly” that viewers can be left with the impression that it is “easy” or that Greg has some sort of unfair advantage. Hardly. Greg's (and Jon's, Stephan's, & Android's, too) mastery is a result of practice and hard work; I think the same can be said of anyone who creates an exceptional art work, regardless of whether it was created with pencil, paint, or pixels.

Blaming the tool or the method is far too easy: why the market is as it is, why people want or expect one type of art or another, is a LOT more complicated question. And maybe we can start to look for some of the answers in future posts.

sure I agree with you Arnie, is not the tool that make a good or bad artist, if someone is good and have the talent and skill is because have been studyng long time to became good, so the the tolls doasn't make the difference, digital, taditional, spray paint…..at the end, the result is a good illustration (like master Artist like Jon Foster, Stephan, extc) they are real artist who became good after long time of hard study and work.

but, unfortunatly, today digital programs give, to the “young artist” who do not have year of experience, so many “tricks” …and then we have every day tousand of new young people in the world looking good with photo manipulations, not even goign to academy, just download free Tutorials on yutube and learn how to trick, the same people without computer, just with a brush and canvas would not even draw a face…..(I'm just talking about new young artist who just started and wanna be good easy and fast)

like all the other Art (dancing, singing or doing Sport or Architecture) there should be “rules” hard work, respect for old guys who start before.

1) keeping the price of the market the same like old artist did for years before us, not try to get work for cheap, or for free… if an Artist live in India, or China and he can live with 300 $ a month, make an illustration in 1 day using tricks…. should keep the price same like US market, otherwise will destroy US market for US and Euroean Artist.

thank you Arnie for give the opportunity to talk about that, it's important for us to share our opinions with the artist around the world.

we should make another forum talking about “price” and artist in the world…

right now we have only few big publishers and milion of artist from all over the world who do not have idea of the price in Europe and US, that send resume and portfolios by internet form home, we should try to keep all the same price from USA to China and Europe to India, if we wanna keep doing this job for the future…….

thank yu Arnie 🙂

all the best

Lucio

The technology of the business continues to change. As always. The principles and the methods of how people work in the business is still as it has always been. It ebbs and flows. There was never a time when it fit the rules or abided by them.

The art world doesn't want 'rules.' Working in the business is about being able to create under restrictions, but we struggle to break out of the restrictions. This is what we love as viewers and appreciators of art. It forces creativity.

No one plays by the rules, or creates by the rules, otherwise we stagnate.

It's not fun, and it's not easy. Frustration is part of it. We'll be fine. The ones who manage are the ones who survive. But if we look around, we find more art being made today than ever.

“There is no such thing as 'cheating' in art.”

This is what CEOs must be telling themselves about business when they use child labour or unfair business practices.

I completely disagree with this blog post.

Painting over photos and painting from a photo is NOT the same. In order to paint from a photo, you have to train your eye, have fundamental knowledge of light/colour/value, understand the underlying structure and perspective, and so much more…the list is endless.

Painting over a photo eliminates a lot of this.

How is it not cheating? Cheating means you're making it easier for yourself. You're skipping over the learning process.

So, please stop telling people who could be spending time reading/learning/studying that painting over photos is OK.

And if you are going to do it, stop insulting artists who work decades on their skillset by calling it 'painting'. Just say it's photo manipulation and be done with it.

There sure are a lot of “experienced” and “trained” eyes reading this post. 🙂

But…you're wrong: there is no such thing as cheating in art. Period.

It is not cheating to “make it easy for yourself.” There is no “one way” in art and everyone does not have to think the same much less work the same way. There is no invalid method to create. There is no superior way. There are only choices. It is not somehow more honest or more noble to work harder than someone else; achieving a work that resonates, regardless of whether the method was “easy” or “hard,” is all that really counts.

You seem to want an absolute “right way,” “rules” that “real artists” have to follow in order for them to be a real artist. And there simply are no rules or absolutes in the creation of art or in being an artist. None. There's lots of dogma, ideology, rhetoric, and opinions, for sure…but nobody has to subscribe to any of them. Artists are welcome to be as non-conforming and rebellious and heretical as they want: that's part of being an artist.

Go shoot your own photo, try painting over it (since that's one of the “cheats” you mention), and see how “easy” it is to do something that looks, feels like, and IS a painting: I think you'll be surprised. You're of course welcome to think whatever makes you happy: art is subjective and not everyone will ever agree about everything.

But that doesn't change the simple fact that there-is-no-such-thing-as-cheating-in-art.

Just because you think there is…don't make it so.

excuse me Arnie, so, it is the same with any other kind of “Art” ?

like for example Music: I can start today to be a musician?

I correct my voice with a computer program…I play guitar with a computer program that gives me a base of Jimmy Hendrix, or another guitar base…a drum base form anohter program…trumpet…bass guitar….and I sing with my manipulated voice on top of them….and this make me feel “happy” and proud of me….so I can call myself MUsician? I'm ready to be a professional Musician and work in the business? …mmm……

what about Sport?

I can drink 1 liter of caffeine before going to run, use cocaine…..and then win my competion against all the other runners who train for months, years before…

or better example…..

Imaigne that I take a Motorbike, and overtake all the other runners….and then I win the competion 🙂

this is Sport? just because I feel happy and proud of me that I win the contest?

sorry giuys, but I have to say my opinion about 🙂 this forum is great and interesting to read how people think different 🙂

have a nice day

Yes my friend, a little bit, I had in fact done exactly that when writing music, I made a few jingles a few years ago all with my computer, I can play guitar and some keyboards, but I'm better at creating music than playing. I fix my vocal with autotune, use a midi keyboard and then I turn everything into guitars, bass, drums even maracas, then I print the music, we hire somebody that can read it, a lady that can sing the note I can and there we go. I'm a little bit of a musician, but mostly a music writer. And seriously, I can barely play guitar and sing at the same time. I can sing pretty descent if I only do that, but for sometime I followed an asshole that almost convinced me that if I wasn't playing an instrument while singing I was worthless, that guy was a huge waste of time.

Anyways, back in the art subject, Drew Struzan said on one of his documentaries about tracing (he uses a projector sometimes) “Artists, hopefully, are not just drawing what they see, but what they understand.”

Also sports are about performance, I have a friend that is a fantastic artist, but he have a policy of “no live art”.

Lucio, the short answer when it comes to music (or any other art), it is all fair. It is not cheating. People my argue about craft and purity and personal aesthetics…but nothing you mention is cheating. It's just different methods to achieve an end and if that end is successful (it communicates, people respond to it, whatever) that's all that really counts. People are welcome to embrace it or sneer at it, but there's nothing “wrong” with it. The creator is still an artist and what they create is still art.

Your sports analogies aren't valid: there ARE rules in sports (whether they involve drugs or motorbikes) and the participants agree to abide by those rules. There are NO rules or restrictions when it comes to art. You don't have to have a degree, no one has to confer upon you the title of “artist,” and you don't have to create your art the same way anyone else does.

I know you feel strongly about credentials and training and are upset about what you view as unfair competition and encroachment, but that's all a matter of personal feelings and opinions. It doesn't change the fact that artists can create (and find an audience) any way they want to, whether you approve of their methods or not. No one dictates what is art and what is not, just as no one can rightly describe any artist's methods (again, with the exception of plagiarizing) as cheating.

Interesting that you mentioned arguing with Penn and Teller about their film, I've recently done just that, via extensive email exchanges with Teller! Arnie, feel free to email me or contact for more info. I'm also in contact with Tim.

It's very true that the end result is all that matters, but how we get there dictates the end result. Teller and Tim argue that the deficiencies of the eye (the center-surround problem) mean that humans are incapable of seeing accurate values and therefore Vermeer (and colleagues) must have used optics to create their paintings.

The eye is indeed weak when it comes to values, but the human brain is highly adaptive and capable of learning not to be deceived. Being able to recognise what is real and what is illusion is at the heart of an artists ability.

Of the two camps, art can't and can be taught, I'm firmly in the latter. Just like all other subjects, it comes down to the will to learn.

Oh, and I agree that no approach is cheating, as long as you are honest with how you got to your end result.

As an art director looking at someone's book my position is less … lightedcanvasart.blogspot.com

This blog information is so good,

jobs

This INFORMATION is so nice so sweet,

sell your art work

Not only is it varying degrees of crutching and cheating but it has flat out ruined the art world by filling up the planet with work by people who have no business receiving widespread viewership or sales. Technology hasn't helped art. We had photographic realists before cameras were invented. Tech has now convinced talentless multitudes that they're artists and your subjective arguments are as delusional as these peoples perceived talent. Their piles of fake art flood the market and make art null, redundant, valueless and unappreciated. Just to justify your shortcomings, or to protect peoples feelings, you spit in the face of the masters who only had paint, paper and a stick. You all are too good for that? Its cheating and its gotten way out of hand. We've already seen the decadence and death of art. Now people are just dancing on the ashes; making fools of people with a real natural skill to see negative space, to intuitively capture the elements and principles of design.

Digital artists (who enjoy immunity from error and anonymity from construction) are the worst, right along side photo print retouchers, projectionists, tracers and ALL ” nonobjective” wall furniture crap that has no meaning, just poop smeared on a wall.

Please don't reply. I've read the whole thread and only 2 people get it. I don't want to read any digital art apologist junk. Tell it like it is and save art for people who have a born ability to make it. Everyone wants to coddle these frauds and respect peoples feelings; at what cost? The dignity and tradition of a millennium.

Neal, I just noticed your, ah, comment. Given your attitude, the only proper response is: Show me what you can do. Show me something that YOU have created traditionally that is a superior work, better than the digital artists you disparage.

PS Unless, of course, your courage only goes as far as your fingertips.

This argument comes up so often that I have stock answers for it, some of them snarky, such as the olde masters didn't have refrigeration, antibiotics, dentists, etc. so when you're ready to give those things up so you can paint like them come back and talk to me.

But the truth is, it's only been very recently that there were any social safety nets, so traditional artists had to make work that sold, or starve. I find it hard to believe that any of them would forsake an easier, faster, better way to produce great work for the sake of tradition.

The 17th century Dutch painters used recipe books for painting still lifes, such as “Paint a plum with these three steps.” They also had pattern books showing fruit, flowers, animals, glass and stoneware, etc. Look at van Huysum's florals. They are known for including flowers that do not bloom at the same time of year. And he is known for painting very rapidly, so how could he have done them from life? He couldn't.

Pieter Brueghel painted a floral for a bishop, and the bishop noticed that one of the flowers in the painting was an exact match to one in another of Brueghel's florals. He questioned Brueghel, and Brueghel swore it had been painted from life, but it had not. It was straight out of one of those pattern books.

Do we fault chefs for using recipes? No, we just appreciate good food. Do we fault musician's for using sheet music? No. Do we go to surgeons who invent their procedures in the moment? No. It's a silly argument to think that one can cheat their way into good drawing, composition or paint mixing.

The computer is just another tool. I believe people make too big of a deal out of it, . . . Years ago, people were afraid of photography too. If you can put together commercial imagery that captivates the viewer, it's working. It is a developing technology whose interface continues to improve. I think of that wonderful retouched photograph used in the Otto Preminger film Laura(1944). For years, many people thought that it was an oil painting; a haunting portrait of actress Gene Tierney as the title character. It did what it was supposed to do, so it doesn't matter how it was created.

I think digital tools are, like every other technology, a double-edged sword. They give with one hand and take with the other. It is now easier than ever to produce amazing visual works, and publish them all over the world. That's the good news. That is also the bad news. Since you can do it, so can a sixteen year old kid in China, so this amazing ability is now ubiquitous and not really worth much in an economic system based on supply and demand. You now compete for attention (and jobs) with millions of artists (how many deviantart accounts are there?), and many more who are no longer alive. As soon as you create something and put it out there, someone else halfway around the world can take it without so much as a thank you. It is enough to make one contemplate the wisdom of Buddhist sand mandalas. Economics aside, I think it is important to remember that the most important and unique thing you can bring to the table as an artist is yourself. The more heavy lifting you let the machine do, the less of yourself will be evident in the result. In that sense, cheating is its own punishment. Style, that elusive quality every artists seeks, is a manifestation of our own personality. You can make awesome images with powerful new tools, but no tool is going to make them truly yours. Only your own imagination can do that. And I think that is what art consumers value above all, and why they consider stuff like tracing to be cheating. It is not remarkable to take an amazing tool and use it to do something amazing. The sense of wonder comes from using an unremarkable tool and using it to do something amazing. The amazing part has to come from you.

Absolutely. Though the devaluation of the artist is a worthy topic for precisely the reasons you touch on, any type of art that finds an audience, resonates, and lasts is and always will be reliant on the artist—on what they personally bring to the work—not the tool they use to create it.

Great discussion! Thank you!

Admin: ePrice.co.in

So glad to have found this! I recently created a watercolor- had it blown up on paper much larger, and painted over it in acrylics, ink, and spray paint. I then mounted it to a board. I could have done it from scratch again but I was so pleased with the origional that I wanted the exact replica only in different colors and media. It has received glorious praise- but I was afraid to explain my technique- even though all the work is origional. Now I feel like I have a few good comebacks if attacked. Thanks for thos��

What an excellent response.

I'm in full agreement trace all you want but you don't have to thee ability to finsh.. that's ..when having the skill to draw comes into play.

Well said Greg.It's funny how everyone can think they know best about art, but if we were lawyers with specialist knowledge, which of course we have, you'd think people would think twice.

You both make good points. Of course part of the skill of a good draughtsman is to edit what he sees; inventively and creatively, to emphasis some things and totally forget others. Therefor it's not the literal but the departure from the literal that matters. It takes a lot of imagination. Amateurs include everything and wonder why it doesn't work…it's just an ode to a photograph. so its not just about observing accurately which is no achievement in my book; just look at the photo realists (it all looks the same)…regardless of the source photo or live model its still the creative that makes the result something else neither photo or painting, a creative-work.

Recently I discovered that a fellow artist has been painting on printed photographs. It was odd to me for a long while that some of her work was very amateurish while other paintings were strikingly realistic and detailed. With a closer look I realized the reason. I can't help but see this as fraudulent and so dishonest. If her work was consistent and she wasn't posing as a painter I might not feel as if I had been lied to somehow. I use some mechanical help sometimes, but I can draw without it, and I would never go as far as painting over a printed canvas and calling it my work. I guess there are no rules in this game.

Man, her nethers are SMOKIN’!!! Great stuff as always, Donato!

I am really impressed to read this article. I am surely going to bookmark your website for future reference.

Effective love spell to get your ex lover, gay/lesbian partner, husband, wife back. Email Lord Zakuza via: lordzakuza7 @ gmail. com

All thanks to Lord Zakuza whose magnificent spell brought back my divorced husband within 48 hours. Email him on Lordzakuza7 @ gmail. com

Great article! As a fan of Al Williamson and his work it inspires hope that I could draw images even a little bit close to his by tracing photo reference.

ps, I would love a tutorial for sale on the site about tracing from reference and inking in the style of Al Williamson, Frazetta et al.