I’ve written in the past about “being a pro” and “unsocial media” and, oh, probably a few other things about about professional conduct for artists. Being a Pro isn’t a one-way street, of course: give respect to your colleagues to garner respect in turn sounds easy enough, right? Unfortunately, it seems that behaving like a pro is something that’s become increasingly easy for people to forget or, more sadly, ignore. In case you missed it, there was a prime example of distinctly UNprofessional behavior that blew up on online February 24.

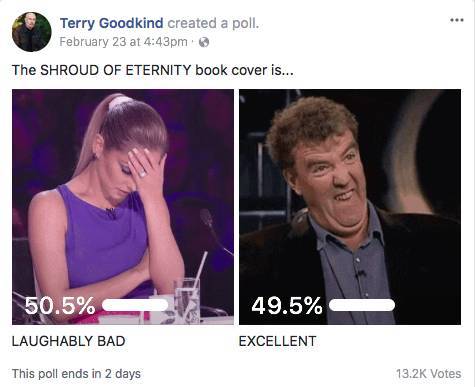

Bestselling Tor Books author Terry Goodkind expressed his extreme dislike for his latest book’s dustjacket on his FaceBook page and Twitter account, describing his own novel as “a great book with a very bad cover.” To add insult to injury, he created a poll (screenshot seen below) and invited his fans to “have some fun with it” and chime in with comments, promising to give out 10 autographed copies of the book to posters chosen at random.

I doubt he anticipated the immediate backlash from readers who, in increasing numbers, described his behavior as “appalling,” “unprofessional,” “shameful,” and, ahem, a “dick move.” As internet news sites and blogs—ranging from io9 to to File 770 to Bleeding Cool to The Guardian to NewsHub—reported on the brouhaha, Goodkind was kept busy blocking critics and deleting comments either valid or snarky throughout the weekend (which almost never helps). He ultimately issued something of a half-hearted apology to cover illustrator Bastien Lecouffe-Deharme, insisting that his ire was really directed at his publisher. Whether his apology was sincere (if lacking) or simply an act of damage control is up to people to decide for themselves; following the close of his poll he made additional mocking comments and posted a video of his dog licking the book cover on his FB page so it’s understandable when his mea culpa is viewed as disingenuous.

But regardless of his stated motive…the artist was the one held up to public ridicule for directions and decisions made by others.

Bastien eventually weighed-in himself, expressing disappointment at being blindsided and treated disrespectfully.

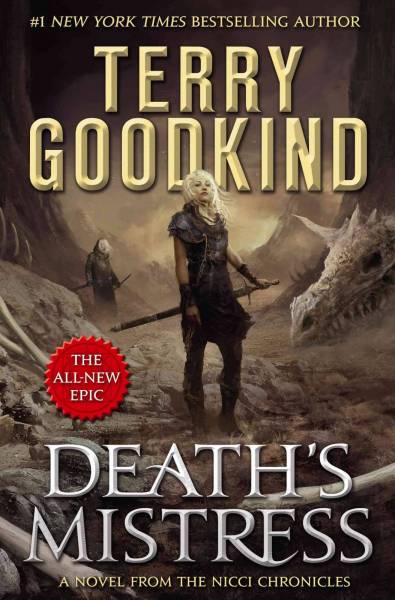

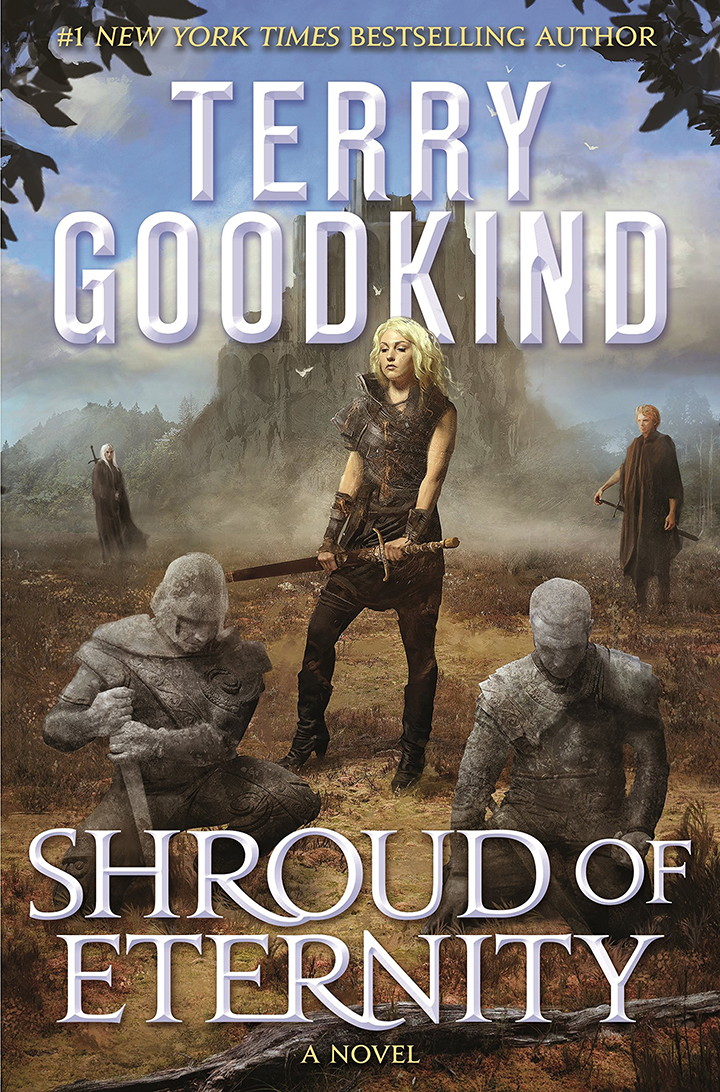

The covers for book series, particularly for genre titles, almost always resemble each other as a way to create a visual shorthand that enables readers to find their next purchase easily. Marketing 101. Goodkind, as far as I can tell, had not expressed any displeasure with the jacket art for the first book in the series (seen above); the second followed the style and direction of the first and had been released 9 weeks prior to his poll without comment. Goodkind had even used a portion of the Shroud of Eternity art for his FaceBook cover image up until the backlash so his unhappiness came as something of a shock to everyone, including, I’m sure, Bastien. (In an odd io9 follow-up piece that appeared a few days later, the assertion was made that Goodkind actually didn’t like the first cover and accused both 1 & 2 of being, uh, “sexist,” supposedly because of the…boots? Suuuurrrrreeeee.)

The other big shock was that as an author of, by his own account, 30 years, Terry Goodkind seemingly didn’t know how the publishing industry works today—and he should.

Surprise, surprise: Book covers are not created in a vacuum, especially as publishing has become less independent and has morphed into divisions of increasingly bigger corporations. I was talking with Lauren Panepinto while we were both watching the social media train wreck unfold and, as an artist/art director/Creative Director she made some excellent points. “An enormous amount of thought and care goes into each and every book cover. A publisher may have different priorities than an author does, and that is part of the expertise you want a publisher to have. An author often can’t see beyond the core diehard fans they have, but it’s the publisher’s job to consider beyond that base to potential fans that may be reached with each new book. The sweet spot we all aim for is pleasing the fans they have with visual easter eggs while appealing to people who have no idea what the books are about.”

“An enormous amount of thought and care goes into each and every book cover. A publisher may have different priorities than an author does, and that is part of the expertise you want a publisher to have.”

And with that goal of growing the audience in mind, the freelance artist, regardless of how accomplished they might be, isn’t granted total freedom to do whatever they want. The cover is a collaboration. While they recieve their brief from—and submit sketches to—the art director, lots of others have input into what ultimately gets approved and printed. The art director, the designer, the editor, the creative director, the editorial director, the marketing team, the sales staff, the publisher, AND, often, the buyers for the major accounts (like B&N and Amazon) have a say. “Make this bigger, make this smaller, add a woman, take out the woman, the monster’s too scary, the monster’s not scary enough, don’t include a monster, make this blue, make this green…” back and forth and back and forth. The freelance artist is never alone in the creative process—but is often left to dangle in the wind when something doesn’t turn out or when a cover is held up for derision. And, conversely, if something exceptional results, if praise and awards and sales come the book’s way, the author basks in the limelight while the artist rarely receives much credit, even though that success is often attributable directly to their ability to incorporate all the disparate input they get and produce a work that connects with an audience.

It’s hard enough making a living as an artist these days without someone going out of the way to kick you in the teeth on the internet.

As I’ve written on Muddy Colors in the past, I’m not a huge fan of the mob mentality that often takes over when controversies arise on social media—little, if any, good ever comes from it and too often the innocent wind up suffering as much as the guilty. But at the same time, when you’re on the recieving end of an attack, hitting back is fully justified and it can be comforting to know that you have friends willing to support you. Corporations as a matter of routine are gun-shy when it comes to internet explosions—no matter what they say, most recognize that it’s rarely going to end well—and it is unusual when they officially come to the defense of someone maligned. That silence can compound the hurt inflicted on individuals, but in this Age of Trolls when even the dumbest stuff can rapidly turn virally toxic…that cautious corporate policy is unlikely to change.

Of course, these types of situations fomented by a colleague shouldn’t happen in the first place, really: business should be conducted professionally and privately and not devolve into public fisticuffs. Public shaming, accusations, and side-choosing is, sadly, the current m.o. in politics as well as business and personal life…and we’re all much poorer for it.

Writers complaining about their covers —or the covers of others— can admittedly be spot-on every once in a while, but from my experience they’re more likely to be be misguided, self-righteous, or pompously self-serving (or all three). It’s hardly anything new (there are even convention panels devoted to “bad cover art”—conducted by writers, naturally): they have personal tastes and visions of what their characters or scenes look like in their own heads and it’s perfectly understandable if they’re sometimes disappointed when the publishers’ ideas don’t always match their own. Some are quite happy with how the covers turn out; some, obviously, are not. But what they rarely know (and even more rarely acknowledge) are all the aspects that makes a good book cover… good. Though it’s nice if it happens, a cover doesn’t exist to please the author or capture their vision in the most minute, exacting details: it’s meant to sell books. Period.

If a cover makes a customer pick a book out of a whole shelf-full of others to look at, half the sales battle is won. Whatever treatment or art that does that—regardless of how the writer feels—is what matters. “That’s not a scene in my book!” or “Thedrica Thickthrew wouldn’t look like that!” they may complain, quietly or loudly to anyone that will listen. And they’re probably right—but their likes and their opinions matter very little in the greater scheme of things. The person whose opinion matters the most? The one willing to open their wallet and take that book home. It is the cover art that often helps make that sale happen—and the illustrator deserves respect.

So when it comes to this particular situation: an author—any author—using an artist (or an editor or art director) as the public whipping boy/girl for other issues they may have with their publisher is little more than disrespectful BS.

Am I picking on Terry Goodkind? No, not really (though his attitude could use some serious work). He can love or hate any artwork he chooses. He can wear his ass for a hat in public as often as he wants and more power to him. And as Dave Palumbo wrote on FaceBook about this particular incident, “I think all cover artists need to face the very likely reality that, somewhere along the line, we really let the author down.” That’s most probably true—but the point of all this is that when true, the disappointed author should take everything into account and not make the artist a singular symbol to lambast. Remember: publishing is personal. One’s actions, regardless of being a “New York Times Bestseller” or not, can and often do have long-term consequences.

What I’m simply doing is reminding everyone, entreating everyone—once again—to be a pro. Being a pro, regardless of which side of the table you’re sitting on, will serve you well in the end. Being a putz in public—again, regardless of which side you’re on—rarely will. (Hmm. “Be a Pro, Not a Putz” is a pretty good motto.)

Grouse as they may, it’s the wise writer who respects what their fellow creatives bring to the table—because, honestly, everyone on the publishing team wants a successful book. As Lauren said to me last weekend, “Sometimes publishers and art directors take risks; sometimes they work out and sometimes they don’t. But to imply that we’re not putting enormous thought into the process is delusional.”

Besides, sometimes not following the writer’s descriptions, not accurately illustrating a scene in the story, can produce results so definitive and iconic that the tail begins to wag the dog. And when that happens… Oh boy!

If a writer can’t respect that simple truth, if they can’t respect the professionalism and expertise of their fellow creatives…maybe they should self-publish and control everything themselves. But then…whom would they have to blame if their book doesn’t sell?

Great post Arnie. Thank you for explaining so succinctly why this whole kerfulle was so bad. Authors definitely need to realise (if they don’t already) that creating a good selling book is not only about the writing but the whole package and the team that work on it. And being professional and respectful to everyone is crucial at all stages of your career.

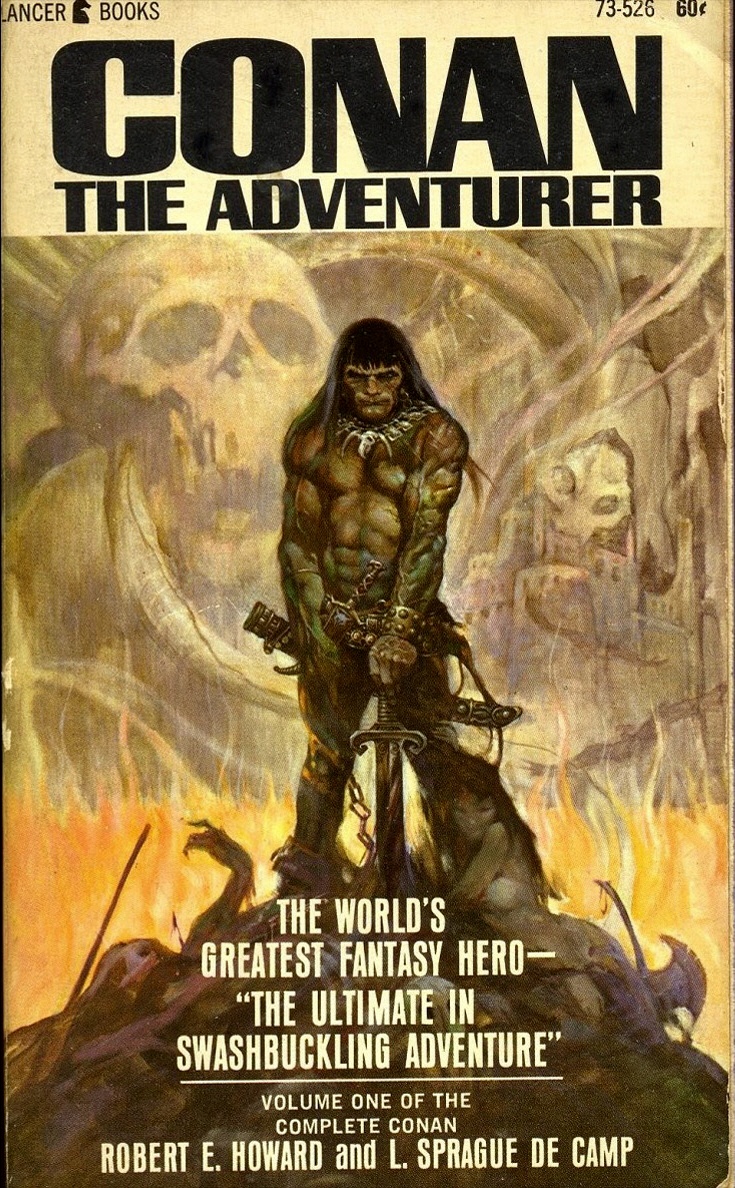

Thanks, Belinda. I think people often have a misperception of the way publishing works today: I sat in a book jacket review meeting Friday that had a dozen people expressing opinions. It can be like running a well-intentioned gauntlet sometimes. I included the Conan cover at the end because the co-author/editor L. Sprague de Camp (Howard, of course, was 30 years dead when the book was published) absolutely hated Frazetta’s cover: in de Camp’s mind Conan should have looked more like Prince Valiant. If Lancer had followed that direction…?

A well written article outside of a couple of points and the closure. Goodkind, as far as I know, didn’t say anything publicly about the previous cover, but I distinctly remember being part of a large group of Goodkind readers who had the reaction “Who are these people?” last time, and that same group of people felt the cover for the second book was so much more disappointing because it was more of the same (as I would expect being part of a trilogy) and this time one of the hugely favorite characters in the entire series is clearly shown wearing high heeled boots in addition to, yet again, people saying “You’re telling me that’s supposed to be Nicci?” before putting their face into their palm and shaking their head.

The high heels aren’t something I believe should be glossed over or scoffed at so much, however. They not only clash with the character, her position and what she is doing in the series (and the trilogy specifically), but are more and more being rejected by women (and people in general) around the world for being objectively terrible for walking in (damaging to your body and painful to wear for long periods of time), seen as sexist and one of many means used to objectify women, an archaic part of women’s fashion, and so on, as well as being one of the bigger faux pas in fantasy art and, simply put, a tired part of fantasy art. As far as I’m aware, in fantasy art communities, comic book communities, and fantasy book/writing communities high heels are put under the same light as “chainmail bikinis” and the like, and create at least as much controversy when worn by any character who is supposed to be taken seriously.

The main point I appreciate is “Being a pro, regardless of which side of the table you’re sitting on, will serve you well in the end.” Too many people on each side or straddling the fence indeed behave too childishly, and I think we all are more than capable of and should be expected to act more responsibly, intelligently, and professionally.

Thanks for your post! Though I fully respect the feelings of writers and their readers who dislike this or that depictions of characters, I think in turn they should respect what the publishing team (artist included in the mix) is trying to do to make the book successful and attract MORE readers. None of them ever go out of their way to disappoint anyone—though, of course, it’s impossible to make everyone happy all the time. Taste always enters into any art-centric equation: it’s a hard row to convince someone who doesn’t like something that it’s “good,” just as its equally hard to convince them that something they love is “bad.”

When it comes to the heels on the boots, honestly, I think it’s simply looking for a hook to hang dislike on. My guess is that if the character on the cover were wearing flats, it would be some other “mistake” to point out to justify the disappointment. While chainmail bikinis are something else entirely, I personally don’t see women wearing heels of any sort as being sexist: if others do, okay, but I don’t and my guess is that the vast majority of women who wear them every day don’t either. But in fantasy fiction? Well, it’s all made up—and since all fiction is a reflection in some way of contemporary life it’s not something I’m going to read a lot into. Which is all neither here nor there, really: it’s Goodkind’s public treatment of an artist merely doing their job that’s the issue, not whether the art is good or bad.

I agree with Arnie in that the boots (and supposed claims of sexism because of the “high” heels) are just something Terry is using to bring yet more attention to his book and continue the kerfuffle. Not at ALL the same as a chainmail bikini. Case in point: the male fashions of the musketeers of the 1600-1700’s: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Stadlinger_Blatt_07.jpg

Looks VERY much like the boots our heroine is wearing. Imagine that.

Funnily enough (or not), I asked a non-artist friend of mine who’s a voracious reader whether he’s ever read Goodkind. My friend (who’s male, btw), kinda winced and said “Yeah, years ago. But I found him really formulaic and well, frankly, misogynistic.” Then I showed my friend the cover in question and explained the recent drama, and he was like “Huh, it’s good. I dunno what all the noise is about.”

Much ado about nothing, is my thinking.

This Indus me of the fuss made by an author when its book’s main black character was portrayed as a white person on the cover.

No, I really don’t think so: this all smacks of bullying behavior, an author publicly inviting his admirers to join in and punch down on an innocent artist. THAT’S what the post is about, NOT about if the cover is accurate or not. If Terry Goodkind has issues, as he claimed, with Tor Books, he should have called out Tom Doherty, not Bastien Lecouffe-Deharme—but since Tom Doherty signs his checks that wouldn’t seem too wise, would it?

Your are right, of course, I was thinking of an author being unhappy with his/her cover. I would not be surprised if Tor dropped Goodking. I will certainly never purchase any of his/her books.

It’s hard to say what exactly will shake out from this. Publishers are in business to make money so if Goodkind’s books continue to sell the relationship will probably continue. Though perhaps a bit more cautiously. Other publishers, of course, take note of Terry’s behavior (publishing is personal. after all) and that might well affect his options going forward. Or not. I guess we’ll see.

One would think that publishing companies would at least consult with the author when designing a book cover, are they not involved in the process at all?

The short answer is: usually no.

Nor should they be. The investment of an author in a work is their skill and time: it’s the publisher that stands to lose financially if the book fails and, as such, they do everything they can think of to make it successful. I have known and am friends with many writers and, God bless them, in my 40 years of working in publishing I have never known one—not one—who knew what it took to make a good cover. Not one who knew more than the art director or artist.

Virtually all publishers show authors the covers prior to publication as a courtesy, but the right to make changes depends on the status of the author and their contract (and usually that right is only granted to the biggest authors whose name alone guarantees sales). Art, design, and marketing are not, as a general rule, the expertise of writers and as such it is almost always smartest to let the experts do their jobs without interference. Everybody has an opinion…it’s just that not all of them are worthwhile. The publishers are taking a calculated risk on every book they buy: I imagine that Terry Goodkind was paid a nice advance against royalties for his series so his internet fussing was really against his own self-interest (unless his actual intent was to create controversy in the hopes of driving sales to sycophants or the curious). REGARDLESS, his behavior toward Bastien was unwarranted and extremely unprofessional: THAT is the point of this article, not whether Tor treats Goodkind the way he believes he should be.

Nice answer Arnie, thanks for clearing that up for me.

And I should say, too, that policies can vary from publisher to publisher; some can be much more open to the authors’ input than others. What I’ve found is that, when people talk with mutual respect, both sides are more receptive to the the other’s opinions. Once the bashing starts on social media, those once open doors tend to close.

pusat celana hernia

Bingo! EXCELLENT post, Arnie. Love that Frazetta analogy at the end too!

Thanks, Dominick! The funny thing is that de Camp wasn’t alone in not liking Frazetta’s Conan covers: his collaborator Lin Carter and the Howard literary agent Glenn Lord didn’t like them either (though all recognized they were selling books hand over fist). Maybe it was a fan thing, maybe it was more generational, I don’t know. Lord even commented once that Frazetta’s Conan was ugly and he couldn’t imagine his having any of the romantic liaisons he had in the book “with a mug like that.” Frank had based Conan’s appearance on himself (as he did virtually all of the heroes he painted) so he was half amused/half pissed when he read the comment in the fanzine SQUA TRONT.

Great post Arnie! I will add, the amount of author input on a cover varies publisher to publisher, depending on that house’s philosophy. When authors sign onto a publisher, they should talk about what the feeling towards covers is in general before they join up. At Orbit we tend to have more author input than most houses, but it still doesn’t mean everyone always agrees on the final product . Luckily my authors understand the term “mutual respect” and know a cover is, as you described, a collaboration of many forces.

Thanks, Lauren. Yeah, as a noted in one of my answers, policies vary from house to house. AMP gets a lot of input from the writers as a matter of routine (but only a relative few have final say). And I have no problems listening to an author’s opinion, especially when voiced with understanding of the process and marketplace along with respect for the creatives trying to do their jobs to the best of their abilities. It’s just when the “autocratic auteur attitude” is displayed that I get bristly. 🙂

Great article, thanks for sharing your thoughts and expertise. I always cringe when I see people complaining about work in public, regardless of what the work might be. It just comes across as unprofessional and immature. And in some cases, dangerous because of the ripples they cause. Also, in this age of global social media, those kind of grumbles that might once have been kept to private emails or work cafeterias or phone calls etc, are out there for the whole world to see. Horribly amplified. Ouch. My motto is, never complain about work in public, so I totally agree with your “be a pro not a putz” line 🙂

Thanks, Candra. And I agree: things said on social media can take on a life of their own and come back to bite people when they least expect it.

Apparently Terry is not living up to his last name.

: )