When I go to conventions and wear a sport coat I often include a pin featuring H.P. Lovecraft’s cadaverous, Moai-ish mug on the lapel; it was a sort of mini-version of the Gahan Wilson World Fantasy Award sculpture and was given to me years ago for being nominated. I never thought too much about it and always presumed that their using Lovecraft for the award was a symbol of genre rather than any attempt to directly honor Lovecraft-the-man. The bust was given out from 1975 to 2015; it was changed in 2016 into a statue of a gnarled tree and moon sculpted by Vincent Villafranca. Why? Well, a controversy surrounding the bust began in the 2010s when several authors objected to using a visage of Lovecraft [1896-1937] as the symbol of the awards, given his racist writings about various non-Anglo-Saxons; Irish Catholics, German immigrants and African-Americans were consistently disparaged in his letters to fans and fellow writers. Lovecraft scholars and biographers insisted that the writer’s attitudes were not considered extreme at the time, were influenced by the late 19th and early 20th century New England society he grew up in, and had “softened” with his age, but winners Nnedi Okorafor and China Miéville noted that they disliked being honored with a bust of a man who would have found many of the winners and nominees distasteful because of their race or national origin. Other writers and editors joined into the debate and in 2015 the award administrators announced the decision to change the award. As Lenika Cruz, associate editor of The Atlantic, notes, “Lovecraft’s removal is about more than just the writer himself; it’s not an indictment of his entire oeuvre.”

Though I personally never considered the award bust as a celebration of Lovecraft exactly (it’s not even a remotely flattering sculpture, after all) or as tacit validation of his racist or xenophobic purview, I respected the objections and supported the decision to change the physical award to be more welcoming to all and reflective of the genre’s diversity.

I still wear the pin, though—and am often asked what it is—but in recent years have started to wonder if I should. I mean, I don’t go around wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with “F*ck Off!” on the front (though admittedly might have when I was a teenager) so is wearing a Lovecraft pin insensitive and somehow sending messages I don’t intend or want to send? Honestly, I don’t know…but it gives me pause.

Last year in my remembrance of Harlan Ellison I had mentioned that, all though he really disliked Walt Disney, Harlan’s house was filled with Disney memorabilia. Toys, teapots, books, plates, and beyond: he had them all. When I asked about the seeming contradiction Harlan had responded simply, “I can separate the man from the work.” Now, of course, I think most would agree that Harlan—who was no stranger to controversy—was an intrinsic ingredient of his writings and extracting one from the other would seem almost an impossible task (as many, whether admireres and detractors, have found).

But separating the Art from the Artist has been a recurring and problematic question in recent years, especially in the wake of the #metoo and #timesup movements. The anniversary of Michael Jackson’s death this past June prompted commentators to wrestle with the question of if it was “ok” to still enjoy listening to “Billy Jean” or “Thriller” in light of past accusations and the recent Leaving Neverland documentary. Similar questions have been asked regarding other singers, actors, writers, and artists that have been accused of (and in some cases admitted to and even indicted for) abusive behavior or sexual misconduct or criminal or offensive or otherwise shitty acts. Often there’s a desire (if not purposeful attempts) to erase the incriminated and their works from society and to ignore past accomplishments whether guilt is ever proven or not. Don’t watch any of Weinstein’s or Spacey’s or Hoffman’s or Polanski’s or Flynn’s or Chaplin’s movies again! Take down Close’s paintings! Don’t laugh at Cosby’s or C.K.’s stand-up routines! Stop listening to Bowie’s (and let’s be honest practically any musician’s, country, rock, or hip-hop) songs! The implication being that by continuing to like their work you’re in some way condoning their behavior.

But does it? The Court of Public Opinion—amplified by social media—can be very black and white and stridently unforgiving. Comparatively minor acts can be conflated to equal criminal ones with the ease of a Tweet.

What’s proper? What’s the right reaction?

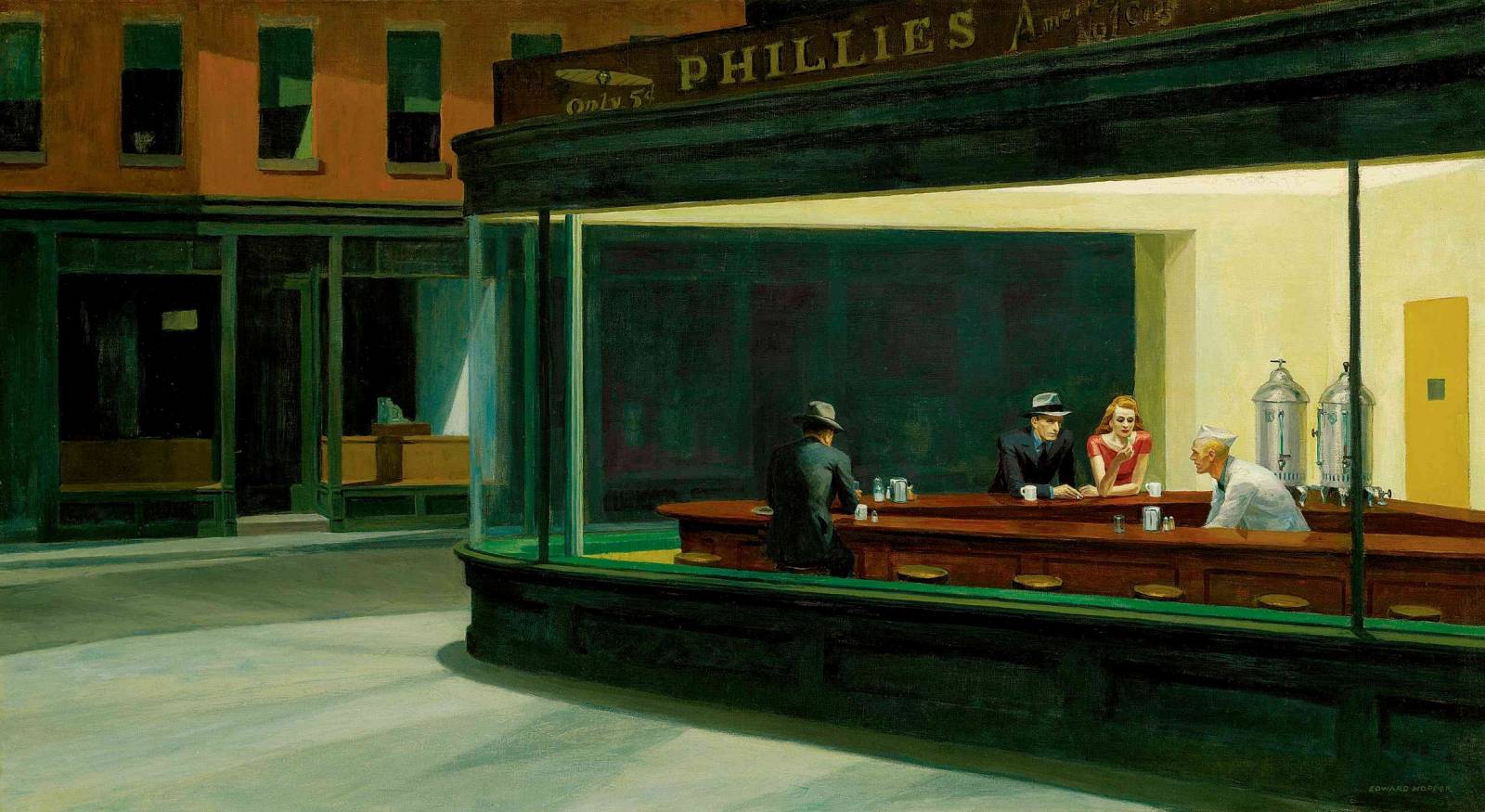

Above: Hopper’s “Nighthawks”

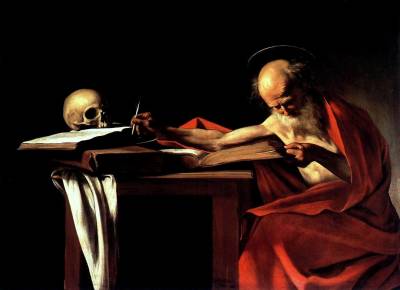

It’s a fact that art is routinely seen as a deliberate extension of the person that produces it, and as such it is hardly a surprise that creator and creation are essentially considered one and the the same. But should it? Michelangelo Marisa da Caravaggio, when not painting his Biblical scenes, reportedly murdered two people; it’s been written that Paul Gauguin battered his wife, abandoned she and their children in France, and had three teenage brides and infected dozens of other underage girls with syphilis in Tahiti; Renoir and Edgar Degas were openly and unapologetically anti-Semitic; in N.C. Wyeth: A Biography author David Michaelis describes an affair the beloved illustrator allegedly had with his daughter-in-law; a nude Georgia O’Keeffe used to routinely chase her then-husband Arthur Stieglitz’s nieces and nephews away from her studio, using a paintbrush as a blackjack; Edward Hopper would mock his wife Jo’s artwork (along with that of virtually all women artists, calling them “incompetent”) and engaged in public fist fights with her—who gave as good or better as she got and only complained to others about Hopper’s superior reach when throwing punches. Looking closely at the lives of any creative (of any person, honestly) will almost certainly find a closeted skeleton or three: no one, including our heroes, leads a squeaky clean life in which they don’t make mistakes or cause someone else pain. I’ve always thought our human failings are as important to understanding accomplishment as are our virtues. People don’t always like to read or hear “bad things” that tarnish their image of an artist that they admire and subsequently may judge the art differently, perhaps negatively. The art, in whatever form it is, hasn’t changed…but the viewer in some way has.

Above: Caravaggio’s “St, Jerome in Thought”

Art, Artists, and Controversy have always been companions. It is both understandable and inevitable that they were and are. Art is a human expression and it goes without saying that being human is complicated and messy—as is history. The problem is that we want everything to be neat and tidy and it never is. It stands to reason that if “good people” can do bad things then “bad people” can do good things—and that includes creating worthwhile art. Saying that shouldn’t confuse anyone into believing that good art somehow excuses the egregious behavior of its creator: it clearly does not. Writing “Imagine” doesn’t give John Lennon a pass for abusing his first wife, Cynthia—but at the same time I also don’t believe that “Imagine” is somehow tainted and should never be heard or performed again. “Imagine” certainly exists because of the artist…but it also exists in spite of him as well.

I’m reminded of the quote from Inherit the Wind when Sarah, the wife of Matthew Harrison Brady, is confronted by a young woman, Rachel, who was hurt by trusting in him: “You see my husband as a saint,” Sarah tells her, “and so he must be right in everything he says and does. And then you see him as a devil, and everything he says and does must be wrong. Well my husband’s neither a saint nor a devil. He’s just a human being, and he makes mistakes.”

But because we like things “neat” there’s often a desire to sanitize the past (and the present, too), and change or hide or even destroy works that no longer fit with one contemporary line of thought or another. I think that’s a mistake. The truth is not partisan, it’s not “politically correct”: though others may try to use it to advance their own causes the only agenda of truth is…truth. As such, I’m all for showing, reading (and reading about), and talking honestly about all manner of art (and artists) whether it’s a painting, a film, a song, or a novel; I’m all for holding people responsible for their crimes and misdemeanors even as I’m all for acknowledging and applauding exceptional work. I want to know the real stories because ultimately that helps me to better understand the artist, their times, struggles, failings, accomplishments, and constraints—and, as a result, perhaps have a greater appreciation for their art. I am 100% for providing context for virtually everything—in museums and in books and online—just as I’m 100% for not hiding anything away, even if it’s sometimes painful. Confronting the unpleasant face-on sometimes is the only way we learn; that’s the only way we progress and, hopefully, avoid repeating the same mistakes.

But that’s just me. I could be all wet.

Will I keep wearing the HPL pin? I haven’t made up my mind and I guess you’ll know when you see me next.

But here are some questions for you (and please, if you choose to post, let’s keep everything civil):

Do you think that art can be separated from the artist? Is it possible to avoid having an artist’s behavior influence the way we see their work? Or does separating one from the other somehow excuse bad behavior?

Wow!! That’s an excellent text, arguments, and line of thought you made.

And I think I agree with everything: we would lose so much if we expected to see only art from perfect people, we would actually lose all of it. But it is crucial to keep everyone responsible for their acts.

I hope they (the artists) understand too, that by admiring their work we are not approving all their behaviors. Would be good that market would also not support they continue to behave like that, especially when hurting others peoples rights – like some recent problems we have seen in the animation industry.

A thing I’ve been hung up on for a while is viewing these questions through the lens of private vs public. Whether or not we are individually and privately capable of separating the art from the artist, I think it is very hard to publicly separate art from artist at an industrial level. When we’re nominating art for awards, for example, it can be very hard to differentiate or separate nominating the art from nominating the artist. Or focusing on art at a festival. Or in a gallery space. Or in a concert lineup. These things all I think blur the lines between art and artist, we like a human story, we like auteurs, and so these are omnipresent in our consumption of these things.

And I think in many fields, especially post-digital-revolution areas like painting and music and film-making, there are often few slots for celebrating things, and many, many things to celebrate. When you’re figuring out to what and for better or worse to whom we will give a platform, whose voices we will elevate and celebrate by selecting their art and their creations, it gets really complicated. I think this is one thing that distinguishes the design of the trophy from the design of your lapel pin, at least to some degree.

I’m wary of anachronistically judging people. If Lovecraft was just typical, but famous enough that we know about his bigotry, I don’t want to judge him. It just makes me a little sad.

But that doesn’t mean we have to keep an award named after him. Changing the name of the award can be a positive moment of ‘hey, we’re making progress.’

This is different than finding people who are now being terrible (Trump, Weinstein, etc.) and outing them. There cancel culture has a better case. This story feels more like keeping ‘all men are created equal’ and stopping naming our fundraiser the Jefferson-Jackson dinner. And the hell with Andrew Jackson all together.

Thanks for the comments so far. As I mentioned, I think providing honest context and allowing others to make their decisions accordingly is much preferable to either blanket sanctifying or vilifying. The problem is that it’s way too easy—and preferable for many—to do one or the other rather than acknowledge that life is complicated. We can’t change the past, but we can learn from it. Just like we can learn from the present. I hope

Good article, Arnie.

Once made, artworks develop a history of their own (i.e. “the autonomous art object”), and new connotations glom on to them irrespective of the artist’s original intentions. For this reason I think artwork can be assessed separately from the artist, though certainly the artist is part of the story.

In history, when a spirit of denunciation has reached a fever pitch, I cannot point to a period where this has not brought out some of the worst in society. Judgement is a slippery business. We are all messy.

For this reason, I look to such as Cervantes’ Don Quixote as a guide. Fight injustice, certainly! But above all let us inspire and exhort each other with visions of everyone as their better selves. And may our vision be tempered with humility and generous heaps of grace.

Beauty and ugliness exist within the same frame. But we have the ability to BOTH look at the picture as a whole, AND to focus on each part separately. Let’s not castigate each other for the moment’s merest contraction of our lenses.

Reading Blake’s Jerusalem, amid all the kookiness of his version of a Wold Newton universe there are what seem to me moments of crystal clarity.

Looking at a film of motor oil in a mud puddle: ecologically, this is offensive. But such (muddy?) colours!

Excellent points, Shawn: thanks for sharing them!

Hello Arnie and Everyone else!

Get topic and discussions so far.

When I experience art, most times it is not in context of the artist as much their time period. I love art history in regards to studying periods the art was created in (looking at the ideologies, political/religious movements, wars, etc etc) but aside from basic knowledge of many artists I always felt that their work and their subject matter was made up events/beliefs of the general time period. The things “egregious acts” they did may not have been as crazy to them as it is to us so why judge them for it? When I look at a piece of art, historical or current, it’s more about my experience with the art and how I get inspired rather than reading up on an artist and then seeking out the work with preloaded opinions from critics or other artists. I feel like I wouldn’t look at much art if I did that latter process.

One issue I’ve had is art which makes money/wins awards vs ones we see online/free. If an artist does INCREDIBLE work but they later are revealed to have been named in a sexual assault allegations do we take the award away? Are they undeserving? I think from a social standpoint hitting people with the message that “you will not win recognition/money for inhumane behavior” is a good one going forward. However, what if all the work from hypothetically “good people” was bad. Do we still award them even if it’s inferior from a visionary/technical perspective? I would hate that because than art suffers. So what’s the solution? I have none but would love to hear thoughts on that. Maybe there are amazing artists who were nice people that no one talks about because they did great work but don’t fit the narrative of a “crazy artist” and you can’t sell books on their life story. Who knows. But I think those artists should be brought to the forefront more (if they do exist).

Personally, I believe that creative geniuses do not necessarily follow normal ideas of ethics or morality. They do what they want because they have the arrogance to. And that personality trait helps them create their art to the degree that they are remembered forever. Or maybe that’s a romantic notion I have. Who is to say.

Interesting, Michael. IMO I don’t think that inferior artworks should be awarded/rewarded by default because the creator of superior work turns out to be a creep. I guess that goes back to what I said earlier that good art can—and does—exist despite the failings of the creator. Just as great art can have disturbing or potentially offensive content for at least some viewers. Art is communication and though we might not always like the “message” it contains or the person delivering it, it still has tremendous value. If that value isn’t apparent today, it might very well be in a hundred years. And, of course, not every worthwhile artist had or has emotional or moral problems or have criminal tendencies. The vast majority don’t…we just hear about the bad players. Thanks for posting, Michael!

Well, in college we were taught that you should separate the poet from the poetry. You were to study the poetry in and of itself without getting into the biography of the writer. A little tough to do especially when it comes to occasional verse. I think to an extent people are influenced by whether you are talking about a living artist or not. I know people who will not see a film with an actor that has a bad reputation, or buy music by certain artists because they feel they are giving financial support to people that engage in bad (sometimes deplorable) behaviour. I personally think it is possible to enjoy art even though I disagree with an artist’s behaviour. I still bring up Bill Cosby routines regularly and laugh about them. But as a fan I do make a connection with artist’s who are still with us. I recall writing a letter to a writer whose fiction had become very dark and had an autobiographical tone to enquire if they were okay. I do not want to go the route of striking off the hierogliphics bearing the names of any ancient pharaoh who became unpopular. And while I agree that having the statues of confederate soldiers displayed in the town square is a bad ideaI do think they should be put in a museum. One thing art does is remind us of the dark days as well as the good ones. There I believe I have muddied the waters sufficiently. I’d continue to wear the Lovecraft pin as a fan, not because I share his personal beliefs.

Time and distance often allows for some perspective, but now days it seems that hurt, anger, and outrage can remain raw and be churned and roiled ceaselessly. And, of course, people can get frustrated when others don’t share their feelings and subsequently lash out at others as a result.

I see the whole Bill Cosby story as a tragedy. Even when he was breaking the color barrier on TV (I, SPY was great), in night clubs, and in the record industry he apparently was assaulting women (some allegations date back to the mid-1960s). As a kid I loved his comedy album “Wonderfulness” and still laugh at “Go Carts” and “Chicken Heart”—which changes nothing. Even as he should be recognized for his professional achievements and any good things he did in his life…he deserves to be in prison.

Thanks for posting, Aaron!

It is always interesting for me to comment on such things because while I am technically what one might consider middle eastern, I also definitely pass as a white person. I like Lovecraft’s work but I do wonder if I would have differently if I experienced the effects of my ethnicity more regularly. He certainly would have considered me ‘subhuman’ ;P

I do however think it is not sufficiently spoken about that not only was Lovecraft racist, but his racism was also at the heart of the ‘horror’ he was writing about. His Innsmouth is his fear of the ‘mixing of the races’ taken to a supernatural extreme. His dark cults definitely reflect his feelings about places where western civilization has not reached, for better or worse. He is not alone in this, Dracula wouldn’t exist without Bram Stoker’s xenophobia (and his weird feelings about sex). So in some ways I feel like not only can we not separate the artist from the work but the work wouldn’t even exist without these flaws of the artist. I’m conflicted myself, for sure, is what I’m trying to say here, I think…

Good points, Doruk. I think a lot of horror and adventure fiction from the late 19th century onto, perhaps the 1970s and the post-Vietnam era were often rooted in suspicion and/or fear of and, perhaps, prejudices toward, other cultures and races. Pulp fiction, comics, and films were full of stereotypes and derogatory caricatures (particularly during the war years), not just in the U.S. but abroad. Lovecraft was hardly alone in injecting his fears and prejudices into his fiction, but I suspect that it was more subconscious rather than a deliberate attempt to send some sort of coded message. I could always be wrong, but I doubt he had much of an agenda beyond making rent money.The same with Stoker. Regardless, I think we’re much richer for having the Cthulhu Mythos and Dracula as part of our literary culture than we would be without them (just as I think it’s fair to acknowledge the failings of their authors). Thanks for posting!

One other thought, during the Protestant Reformation certain radical elements began destroying stain glass and sculptures in churches because of the word not to “make any graven images.” You can visit churches to this day that have white walls and at most a cross up front. But when Luther was consulted he denounced the practice of destroying or white washing over painted art. His reasoning was that God shone through art and in various ways (even though Luther came down solidly on the word) including hymns and artwork. While I will read Shakespeare aloud to the chagrin of my kids, I tell them we’ve gotta go see this performed on stage. There is a living vitality to art and often it is more than the artist that shines through. In fact I was first captivated by Ray Harryhausen’s movies long before I knew who he was. The question, “How did they do that?” was secondary to being amazed by Jason and the Aurgonauts.

So glad you brought this up, and where you’re at with your article is exactly where I am at as well: It seems wrong to take the artist entirely into account and it also seems wrong to NOT take the artist and context into consideration when judging an artwork, and yet, so many pieces of art transcend their maker.

I think it often comes back to the definition of an artist as a channel for their times. Some artists are more plugged into the collective unconscious than others, but all are in a very real way, “translating” their times into something personal, that can then influence the emotions and thoughts of their audience. Artists are the mirrors we see ourselves and our culture in Sometimes that mirror is dark and tarnished, and sometimes it is clear and bright. Both affect the image we see, irrefutably. But everything that is in the image is not 100% a product of the artist alone.

Lots to chew on here, not sure there is a “right” answer, but an important one to keep discussing.

All excellent points, Lauren!

One of the things I’ve been wondering about is how to provide just-the-facts context without the act itself getting turned into some sort opportunity to advance causes or agendas. Who gets to decide where the line is, who determines what’s context/history and what’s editorializing? Heck if I know!

Thank you for such a nuanced discussion—it’s a valuable perspective for both artists and art enthusiasts alike!