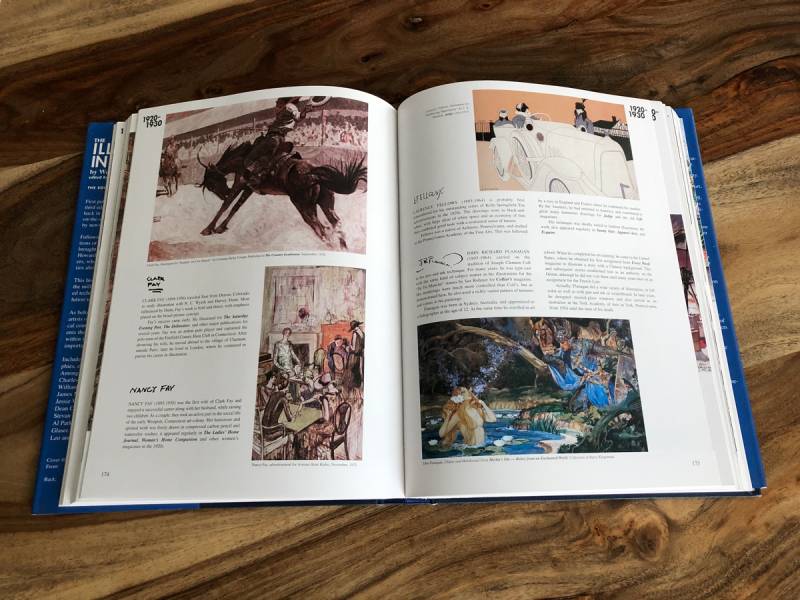

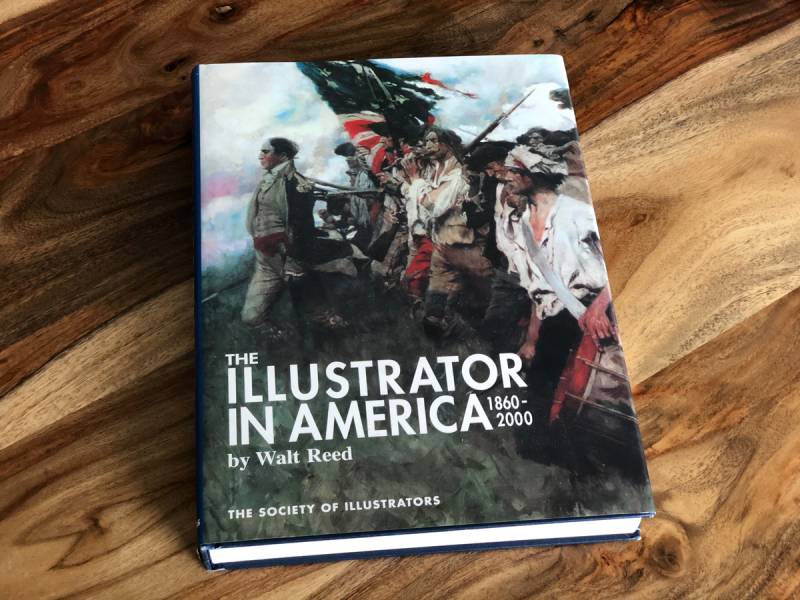

Years ago, I got a copy of this book, The Illustrator In America 1860-2000, by Walt Reed. If you’re unfamiliar, the book is basically an encyclopedia of prominent American illustrators that worked—not surprisingly—between the years 1860 and 2000. Each entry includes a biographical blurb, and one or two examples of the illustrator’s work. All in all, the book is a pretty nice resource in terms of the history of American illustration and it’s a great starting point if anyone out there is looking to expand not only their knowledge, but gain visual inspiration.

What is particularly nice about the book for me is that it’s not just a list of folks who I don’t know and have never met. Indeed, I’ve had the good fortune to meet a few of those who are featured in the latter section of the book covering the modern era‚— a few of those I’ve even managed to get to know beyond a mere cursory level (among them my fellow Muddy Colors contributor, Greg Manchess), and even had the fortune of being taught by another name found in the book (shout out to George Pratt).

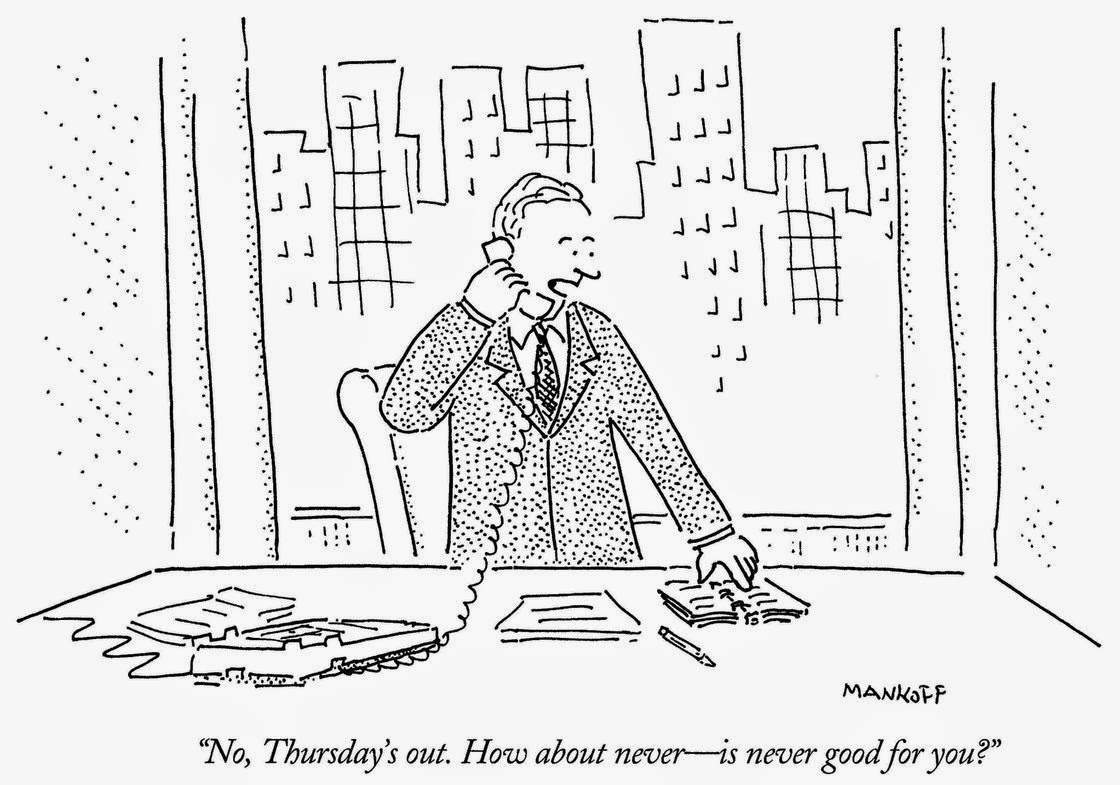

One of the weirdest (and very necessary) aspects of this book is the distillation of entire careers into one, single image. That had to have been among the more difficult things to do in making this book.

Anyway, this book is an education unto itself since it goes well beyond the biggest of the big names in American illustration. It’s pretty exhaustive honestly, and features more than a few lesser-known folks in the business. While the reader may not recognize every name, each illustrator featured was quite relevant in their own time, with many remaining relevant to subsequent generations and beyond.

As exhaustive as the book may be, it’s far from complete. I mean, how could it be? There’s only so much room within the volume and difficult decisions needed to be made. For much of the time in history that Reed’s book covers, illustration was far more ubiquitous. Books, magazines, every advertisement, every theater or movie poster—even shopping catalogs—all fecund with illustration. All that work required a lot of illustrators—far more illustrators than could ever fit into a mere 450 pages.

Of course the world moved on and illustration became a bit less prevalent. Still illustration found new niches to fill and types of work that once didn’t exist suddenly became a thing. And so there continued to be—and still are—a lot of folks toiling away at their drafting tables, easels and (now) computer screens creating illustration. More toilers than a single volume can cover.

And so Reed’s book only tells a sliver of the story. For every illustrator named, there are probably hundreds (possibly thousands) of working illustrators whose names didn’t make the cut, yet were plying their trade and making a living at the time. Compile 140 years worth of illustration history, and the list of working illustrators that had to be left out would probably astonish. Add to that the work of illustrators outside America, and well…there’s just too much to cover. Heck, if a volume were printed just to document one year of illustration today, countless names would STILL need to be omitted to keep the page count from climbing impossibly high.

Of course, the reason for any one name’s omission could be anything. Maybe there was a lack of opportunity. Maybe it’s because the style they worked in fell out of fashion. Maybe they worked in a genre or niche that just didn’t have as high a visibility. Or maybe they didn’t know the right people. Who knows?

To me, the reasons don’t matter.

What matters is that there were folks out there doing it. They were illustrating. For a living. Maybe it’s bad luck that their names were lost to history. Or maybe they were never concerned about that in the first place. Either way, I don’t feel there’s any shame in it. They made a living—even if only eking one out, they still made it.

Personally, I don’t expect to ever make the cut for a volume like The Illustrator In America. If the greats included in such books are the tip of the iceberg, I think I’m comfortably part of the rest of the berg. The much vaster part that’s underwater and dangerous to passing ships. What recognition or notoriety I’ve managed to receive hasn’t really been something I’ve expected or seen coming. It’s also something I could happily live without. I’ve always just focused on staying afloat, concentrating on the job I’m working on and worrying about lining up the next one. I suspect that most folks reading this—not to mention the folks both in and left out of Reed’s book—would understand that.

My Mom always liked to point out to me as I grew up that “life’s tough.” I’d like to add, “and so is this business.” I got lucky. I had a lot of support when starting out, and with that help I managed to cobble together a career doing something I love. I was a little slow to recognize the difficulty of the job and how fortunate I was (and still am). A lot of folks never manage to make it to a place they want to be in the business and it’s tough to get a foothold. That anyone can make it happen and keep the plates spinning is kind of magical. In my opinion, any level of success one attains in this industry—even a little win—is worthy of no small amount of pride.

Still, it’s not wrong to want to become a recognizable name. We all have different interests, different ambitions, and different definitions of success. I think it’s great if getting into future editions of Reed’s book (or a similar volume) is what’ll help you become the you you want to be. But if you don’t have any interest (or don’t manage to make the cut), just remember that you’re not alone and you’re in good company. The vast majority of those in the industry are right there with you.

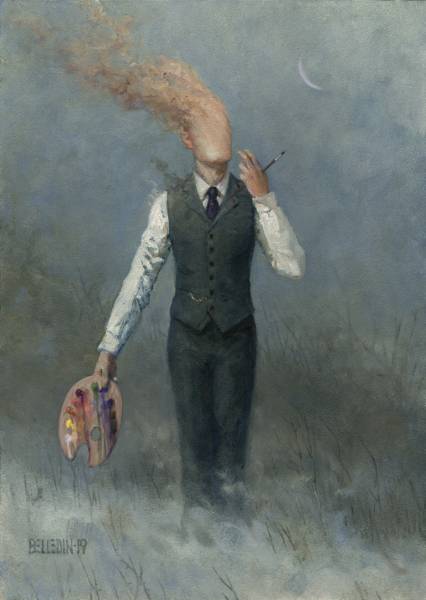

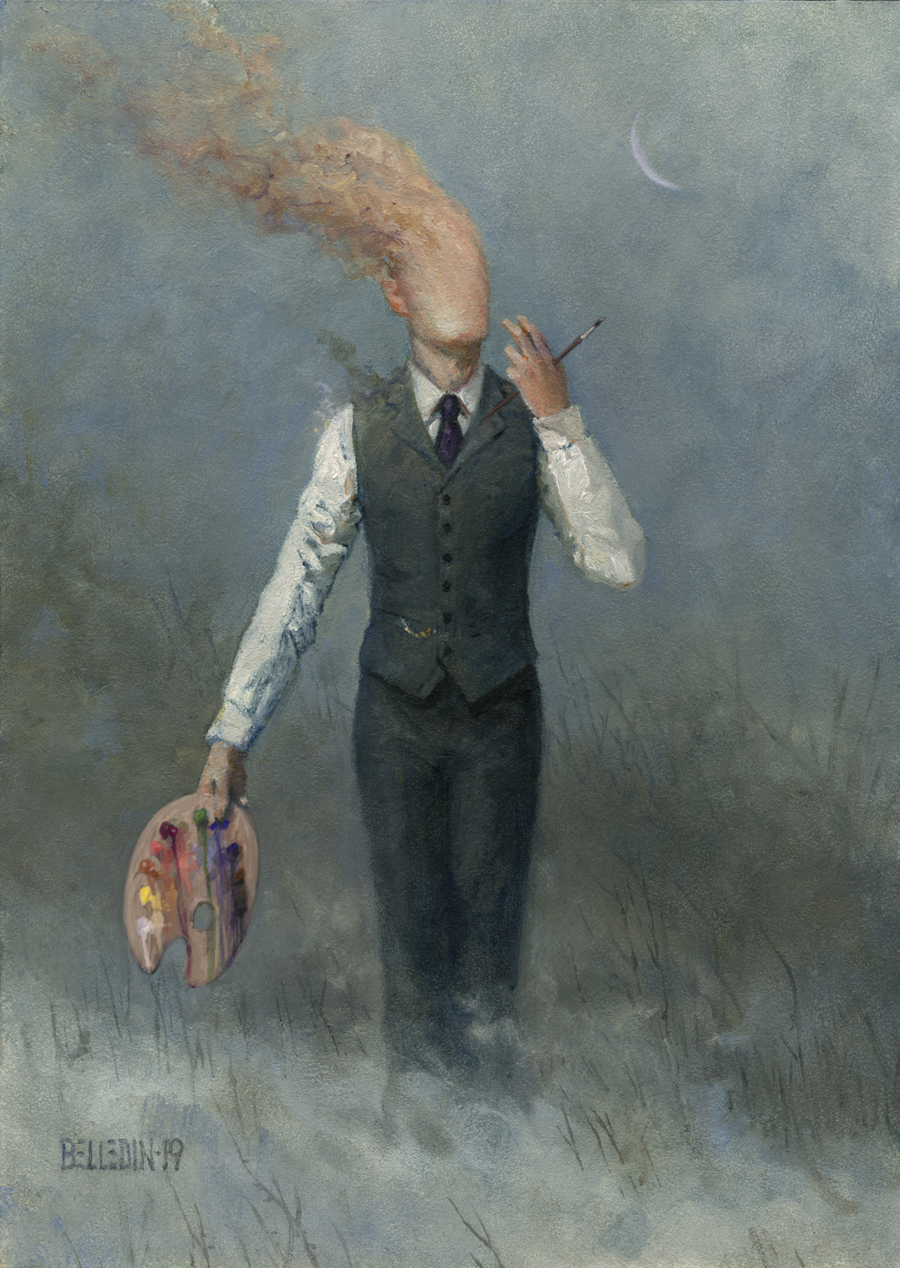

On some level I guess this post touches on legacy, but it’s hard to get into that in depth since it’s all so personal. Weirdly, I’m unconcerned about being mostly forgotten. I wonder whether my that has something to do with the poor quality of my own memory. Anyway, here’s a piece I did earlier this year that’s 5″x7″, oil on hardboard. The palette and brush were added digitally as it seemed to thematically work with what I’ve written.

I’ve toyed with the idea of making a website/index of Illustrators. To do the artists any justice would require a mountain of effort. Like most things, I people would love and abhor it.

This text was unexpectedly right in the feels