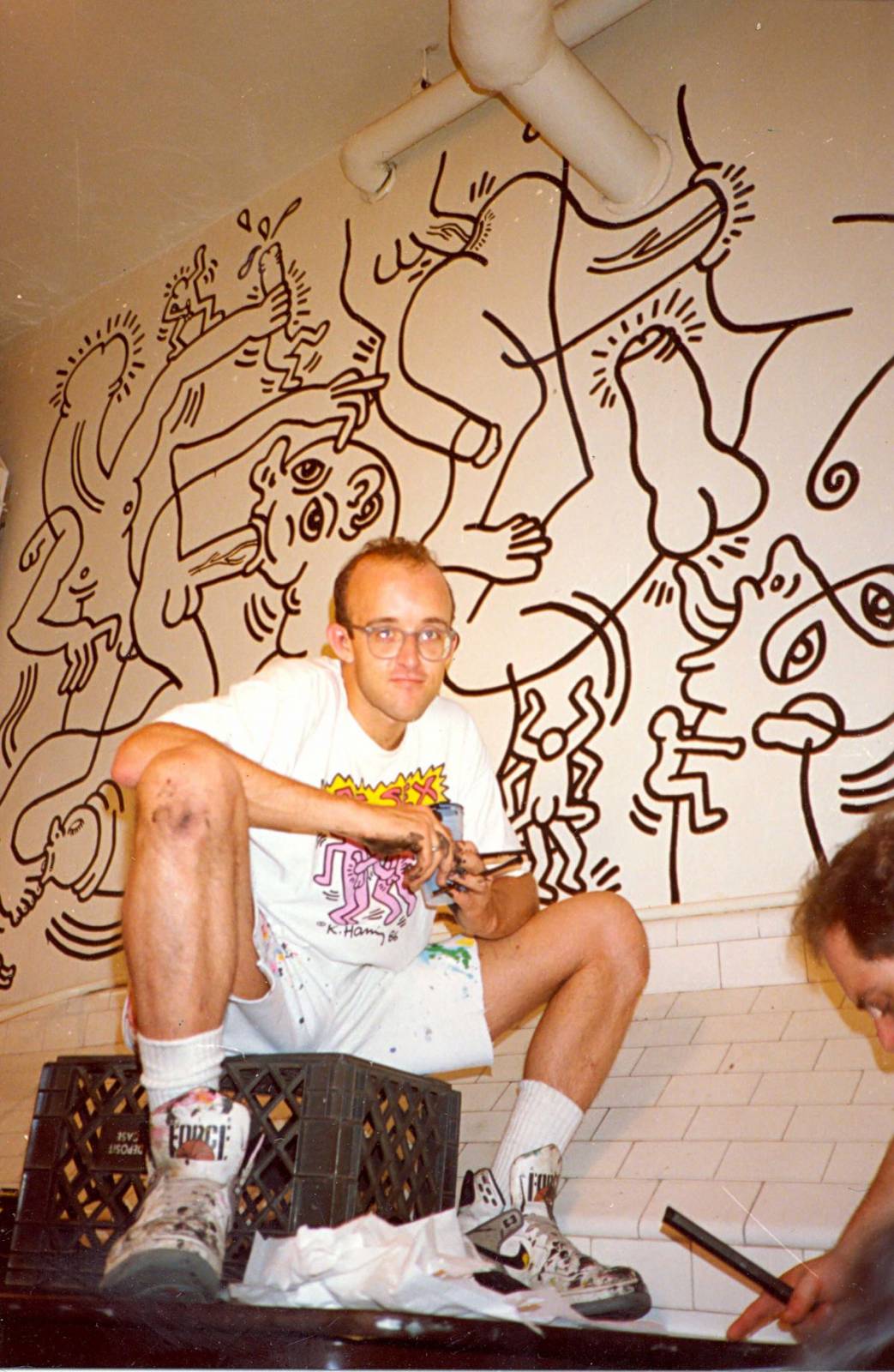

My final post for 2019 is devoted to Keith Haring, of whom I’m a big fan. I chose him because of the way in which he placed his sexuality in the foreground in both his work and his personal life. Although I’ve questioned the ways in which he had appropriated, packaged and sold black culture to mass audiences using graffiti as his platform to tell his stories, I deeply appreciate his social activism through his art and the way in which he actively supported LGBTQ rights and HIV/AIDS issues during a time in our history when we were feared and dehumanized by most of the world, and then cast off to the wilderness.

This piece in particular feels very special to me because of how accessible it is. It’s located in what used to be a bathroom at the LGBTQ Center on West 13th Street near 7th avenue in the West Village. I saw it for the first time when I came out of an AA meeting years ago. It was one of my first meetings and feeling uncomfortable and confused by my new sobriety, I stumbled upon his artwork as I was going up the stairs. I remember I’d caught a glimpse of his recognizable black and white curvy lines, and as I entered the room I wasn’t sure if I was allowed to, or not. I felt like a trespasser. But there was no security guard asking me to leave, or anyone else. And so I stood there oddly in the room, alone. It was during a time in my life when it wasn’t my sexuality that was plaguing me, rather how much booze I was drinking. Although I didn’t analyze the pictures that enfolded above, it felt like a moment of respite, like I was in a sacred place, my own tiny chapel in the middle of the city.

~

There’s a playground where men climb naked up and down phallus poles, swing on pendulous scrotums, and shoot out of foreskin tube slides. Curvy shapes and thick black lines meander and vibrate wildly next to each other. Looking even more closely at the scenario, the lines turn into body parts and then into monsters that spit and suck. It’s a Cocteau-Dubuffet-Alechinsky threesome in a West Village bathroom. Keith Haring draws a gathering place for his men to live carefree — it’s a garden of gay earthly delights that celebrates male homosexuality. Haring painted his mural in 1989 during the AIDS epidemic when America was afraid of gay male sexuality, and then died nine months later because of it. His radiant child has morphed and now it has a penis head. The baby crawls on all fours along the floor, one eye open searching for something to dock into. Hungry meat-sacks run and jump while flinging about their exposed cocks and holes, their eyes bulging and tongues lapping at the air.

The public restroom isn’t a place where you might expect to have a party. It’s a private site that’s filled with piss and shame. Don’t look, don’t touch, and don’t make sounds. However, in the toilet stalls and dark corners are the places where you can find sexual pleasure. At the end of every night although these areas get scrubbed and sterilized there is always some ghostly excrement beneath. Haring tilts a light to these blemishes – the handprints, the cum stains, and the foot prints come to life as evidence of where men once were and the naughty things that they’ve done.

This is a colourless room built on a binary system: black and white, curved and rectilinear lines, gay and straight. There are no colours in between, not even grey that could give new meaning or nuance to his marks. Haring paints lines that bend and undulate within a space that is restrained by the only horizontal and vertical lines of the walls, floor and ceiling. They become the container that tries to hold, organize and straighten out the curves.

Dickheads dance with boners while men feast on assholes and offer a toast with their dicks to the two cocks in rings bound by their vows. Giant sentinels are ushers that guard for any intruders who might disturb their queer matrimony. Haring recovers a space that existed a long time ago and invites all of the lovers and friends who have been shamed and shoved to society’s perimeter for wanting same sex love, to come back to the center for one last indulgence into their sexual pleasures. Haring’s frieze tells a story of life before AIDS. He builds a space where sickness and death aren’t allowed to enter and where time stands still. Here, these men’s lives can’t be erased, or discarded.

Thank you for posting this. Thank you so much. Like you I am a queer person and a recovering alcoholic (in fact, it’s eight years today). Being faced with sexual imagery in art has a bracing effect on me in part because of the shame I internalized being brought up in American culture. But as I get older I understand how powerful it is, not just as a source of shock or titillation, but as a way of subverting the puritan mindset that keeps people closeted and miserable.

Our culture is very conflicted about sexuality. On the one hand we’re all brought up to be ashamed of sex, treating it as a necessity for conception but “dirty” in any other context. But then that shame is exploited in advertising, political ideology, pop culture, etc. The repression of sex has an impact on everyone, not only queer people. But LGBTQ people have to push back harder against that repression than straight people do, and for this we are both hated and envied. Queer people, by our existence, threaten dogmatic ideas about sex and gender. LGBTQ artwork that explores this experience of otherness is often considered offensive.

I love Haring’s work now more than ever. It took me a long time to understand what he was doing and how important it was.