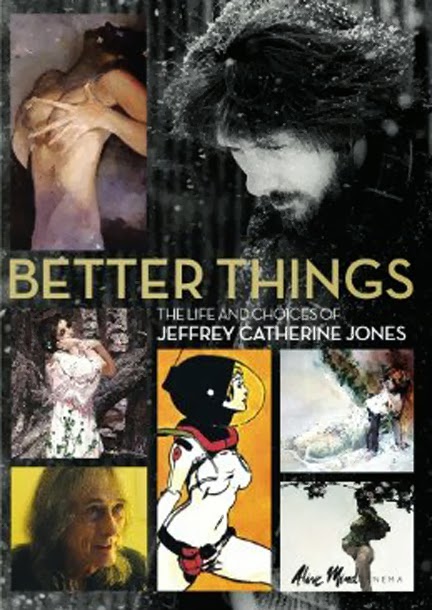

Next month Maria Cabardo’s documentary, Better Things: The Life & Choices of Jeffrey Catherine Jones, will be released on DVD. It’s a heartfelt film and Maria did a wonderful job while facing difficult challenges; Cathy and I are proud that we were able to help a little as Executive Producers just as we were proud to premiere the movie at Spectrum Fantastic Art Live 1 in 2012 as a way to mark Jeff’s passing a year earlier.

Now Irene Gallo is organizing a major exhibition of Jeffrey’s art at the Society of Illustrators’ Museum of American Illustration which will run from March 5 to May 3 in New York. Relying heavily on the extensive collection of Robert K. Wiener plans are also afoot for a screening of the documentary sometime while the show is hanging. Since his professional career took off when he and his family moved to NYC in the 1960s, it seems appropriate that his first museum show take place there.

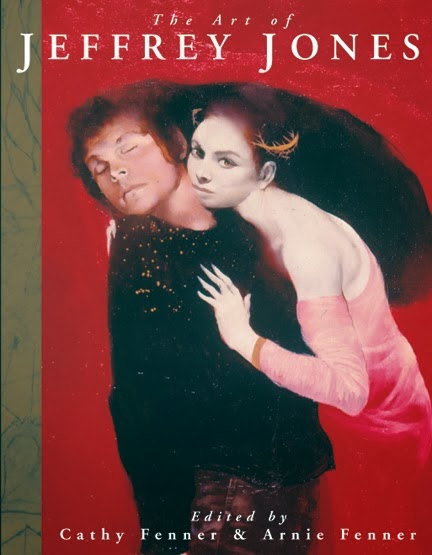

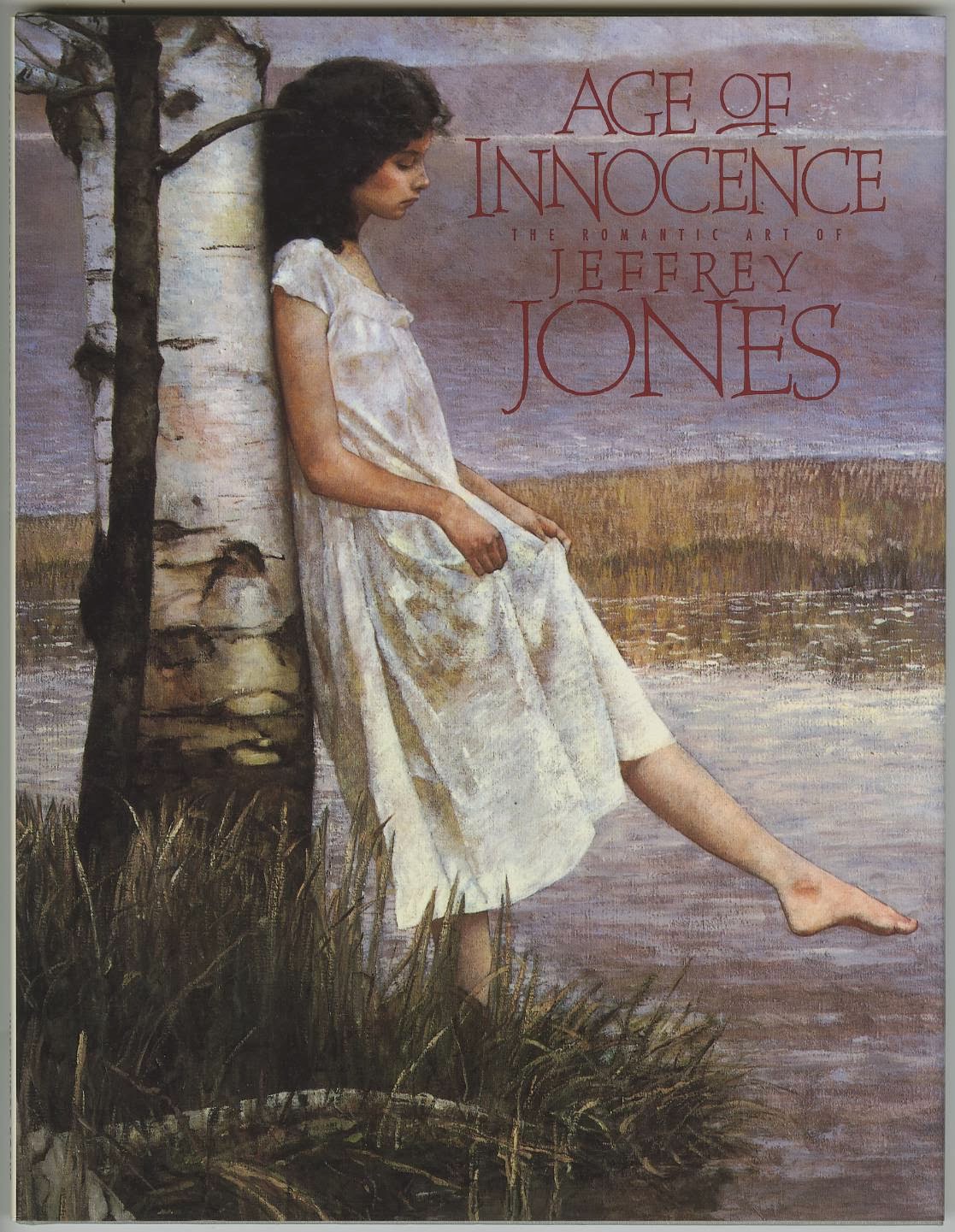

So Jeff is getting some welcome recognition from a wide variety of sources: what he would have made of it all is anyone’s guess. We had produced two art books with Jeffrey and the experience was both frustrating and rewarding—which pretty much sums up everyone else’s experiences with Jeff through his lifetime. I thought I’d reshare this slightly modified essay I wrote several years back to celebrate, to remember, and maybe explain a little bit who Jeffrey Jones was.

I’ll be the first to admit that I did not really understand Jeffrey Jones. He was at once contradictory and perplexing and inexplicable as an artist and as a person; an odd amalgam of illustrator, cartoonist, and painter; a philosopher, a sly comedian, and a nerd. His transgender exploration, rather than providing concrete answers only succeeded in making his story even more confusing. When asked to explain “…what’s up with Jeff?” in recent years I could only shrug in reply. I always tended to think of Jeffrey as a fragile and somewhat lost soul, but—again, contradictorily—also as a person of great strength and resolve.

The one certainty was that I liked Jeffrey: I respected his work (and there was some that I truly loved), I admired him. His art—whether created with paint, pencil, or pen—was inspiring, evocative, and memorable; as a person, he was thoughtful, humble, and kind. There was a southern charm and gentility about him that tended to emphasize his emotional struggles and often elicited both a pang of sympathy and a feeling of sad frustration.

Jeff started out as a science fiction fan—an amateur rocket enthusiast and avid reader of Heinlein, Bradury, Campbell, and Clarke—and honed his artistic skills drawing for fanzines like ERBdom, Amra, and Trumpet. He turned pro illustrating comic stories for Eerie, Creepy, and Flash Gordon as well as providing paintings for Red Shadows, a hardcover collection of Solomon Kane stories published by Donald M. Grant. A move from Atlanta to New York with his pregnant wife, Mary Louise “Weezie” Alexander, led to a career creating paperback covers; he was fast, versatile, and had a style vaguely reminiscent of Frank Frazetta’s (who was much in demand, but rarely interested in increasing his workload), all of which made him extremely popular with art directors. Besides providing paintings for books by Fritz Lieber, Jack Vance, Andre Norton, and Robert E. Howard, he produced numerous romance, adventure, horror, and spy covers. Jeff also maintained a relationship with the comics industry and for a number of years provided monthly strips for National Lampoon and Heavy Metal. But even as his popularity grew and the quality of his work increased, he became more disenchanted with commercial art and his life in general. Jeffrey always seemed to be searching for something—just as he was never quite sure what that “something” actually was. Following a separation from Weezie, he and his friend Vaughan Bodé openly experimented with cross-dressing (which Jeff had been doing secretly since childhood) and female hormones, but both became alarmed with the changes taking place in their bodies and stopped the treatments.

He produced some of his most accomplished paintings while a member of The Studio with Michael William Kaluta, Bernie Wrightson, and Barry Windsor-Smith, but the experience meant much less to him than it did to observers who desperately wished that they could have been a part of it. A difficult childhood relationship with his father, the dissatisfaction with his career path, his failed marriage, his self-doubt about identity, and Bodé’s accidental suicide in 1975 undoubtedly contributed to Jeff’s abuse of alcohol and ultimately his clinical depression. He once said, “My life describes the stories of boys and men for thousands of years: boys who were beaten by their fathers, boys whose capacity for love and trust was crippled almost at birth. Men, whose best hope for contact with other human beings lay in detachment, as if life were over. It’s how we keep, in turn, from destroying our own children and terrorizing the women who have the misfortune to love us, how we absent ourselves from the tradition of male violence, how we decline the seduction of revenge.” He was hospitalized several times through the years when his emotional turmoil became unbearable.

In the late 1990s Jeffrey renewed a series of treatments with female hormones, married Maryellen McMurray, added “Catherine” to his name (though he never changed it legally), began dressing and living as a woman, and came to be described as “she” by many. Family and long-time friends, however, continued to call him “Jeff” and refer to him as “he”: it wasn’t out of disrespect or a disapproval but a reflection of their long-term relationships—and Jeffrey was comfortable with it, unlike those who didn’t know Jones as well and who would express their consternation and anger online on Jeff’s behalf. The truth was that the changes compounded his unhappiness rather than resolved it. The fairly quick dissolution of his second marriage made matters worse; an arrest for a traffic violation and being held in jail with the male population was his darkest period. Tim Underwood came to Jeffrey’s rescue and posted bond for his release, but the trauma was too severe: he experienced a mental breakdown and prolonged hospitalization beginning in 2002. Jeff lost his home and small studio and only made it through the hard times with the help of his daughter Juliana and friends Robert Wiener and Allen Spiegel. Though eventually he was able to move into a small apartment and begin to paint, Jeff was never entirely whole again: his new art lacked the skill and, above all, passion of his earlier works. Conversely, he became very active on eBay and Facebook, selling sketches and interacting with an expanding circle of fans and admirers.

For a time, through my ignorance, I never knew how to properly address Jeff after the hormone treatments and the adoption of the Catherine name; he never identified himself as Catherine when he called to talk about projects. It’s often been misreported that Jeffrey had undergone sex-reassignment surgery, but he never did (and said he had no intentions of doing so); I had always known him as a lanky, bearded guy and he was distinctly male in all of the photos he would send Cathy and me for inclusion in his books. So there were decidedly mixed signals (for a reason, as it turned out) and I was flummoxed as to what to call him in emails or conversations or when writing about him…so I finally asked him directly years ago around the time that we were working on The Art of Jeffrey Jones just prior to his major collapse. He told me to call him “Jeff” or “Jeffrey” and since the law considered him a man, it was perfectly fine with him if others did, too.

Though he lived the rest of his days as a transgender woman he told me candidly in 2006, “It was a mistake. I was convinced that my turmoil was because I was a woman trapped in a man’s body and for a time I was happy with my decision. But I came to realize that I still think like a man and desire women like a man does. I thought it would make me less depressed and I was wrong. I drove down a dead end road and now I can’t back up or turn around; the only thing I can do at this point is accept things as they are. And I think I have. Besides, what other choice do I have?”

We had asked Jeff how he wanted his nameplate to read on his Spectrum Grand Master Award and it says, per his instructions, “Jeffrey Jones.” “That’s how people know me,” he said. “That’s how I want to be remembered.”

The easiest thing some might say about Jeffrey is that he was born out of his time; others, of course, would agree with his occasional statement that he was born the wrong sex. He has always been portrayed as a brooding and mysterious talent, both troubled and romantic: the Byronic figure of the fantasy art world.

And perhaps he was. But for my part, I’ll always remember Jeff as someone who was on a journey that was sometimes uplifting, sometimes terrifying, and sometimes heartbreaking—but he always had hope of finding a place where he felt he truly belonged. Like so many in our field, Jeffrey Jones’ brilliance was both a blessing and, sadly, a curse.

I hope finally, at long last, he has found the peace that he was looking for and so deserved.

Thank you for the insightful and gentle tribute. I have always loved his work.

Wonderful Arnie. Thank you.

This is such a touching post about such a great artist. Looking forward to the DVD release of the documentary. And I had no idea that book existed…going to have put that one on my list of things to find.

Beautifully written Arnie. I'm glad you cleared the air regarding how Jeff wanted to be known and addressed.

Arnie, others have articulated what I feel about your wonderful essay. Jeff remains an inspiration to me as an artist. His work still amazes me.

What an immense strength to still even pick up a brush and paint after such hardships. Albeit a sad story, what an inspirational person. Thanks for the tribute, and this documentary will be sure to please.

Brilliant cant wait!

Thanks for the kind words, everyone!

I knew Jeff ´s works in the spectrum world. His art is amazing . His life is unknow for most of the people so your post is a chance to know how this artist lived, in happiness or sadness.

Thanks for posting this, Arnie. I was in correspondence with Jeff and he suddenly disappeared. I eventually found out what had happened and he did resurface, but this fills in a lot of the gaps.

Thanks, John. I knew Jeff's health had been fragile, but didn’t know exactly how bad things were until shortly before his death. I was talking with Rick Berry last February in Boston and he said that Jeff had actually rallied in his final year because of Maria’s documentary: Jeff wanted to be around to help her complete it. 🙂