“Be a pro.” Sounds easy enough, right? Do your work, deliver what you promise, try to make every job your best, be on time, show your client courtesy…you know the drill. Of course, not every job goes the way you might like, not every client is a saint, and sometimes there are frustrations, misunderstandings, miscommunications, slow paychecks, and any number of other things that can raise your hackles: it all comes with the territory. Generally, you take everything in stride, solve problems the best you can, learn from experience, and move on to the next job.

But sometimes, just sometimes, something sticks in your craw. Sometimes there’s an incident—or series of incidents—that make you want to cry “Havoc!” and unleash the dogs of…Facebook or Twitter or other social media platforms to “get some payback” on the Orcish Overlord who poo-pooed your sketches or paid peanuts (if they paid at all) or in one way or another cheesed you off. Make it loud, make it public, encourage the internet hordes to chime in with commiserating posts full of piss and vinegar! That’ll show ’em! Yeah!

But it never does. Not really.

While it might initially seem like you’ve “given them what for” and caused some embarrassment or consternation for the source of your ire, all you’ve actually managed to do is share your private business with a huge number of people who, regardless of any words of support, really don’t care; all you succeed in doing is burning a bridge while you’re standing on it, one that someday you might want to walk back across. Everybody loves nasty gossip—it’s human nature—and posts can stick around and be shared and commented on and reshared long after the initial anger fades—and ultimately have unforeseen consequences.

Because…think about it for a minute: having a career in the arts is a matter of constant interactions, of collaborations, whether with art directors or publishers or editors or producers or studio execs or gallery owners: when it comes right down to brass tacks, it is an employer/employee relationship. It doesn’t always make them right and you wrong (or vice versa), but there is something of an obligation to treat the people you’re working for with the respect their position deserves. Particularly when you want them to write you a check and hire you again in the future.

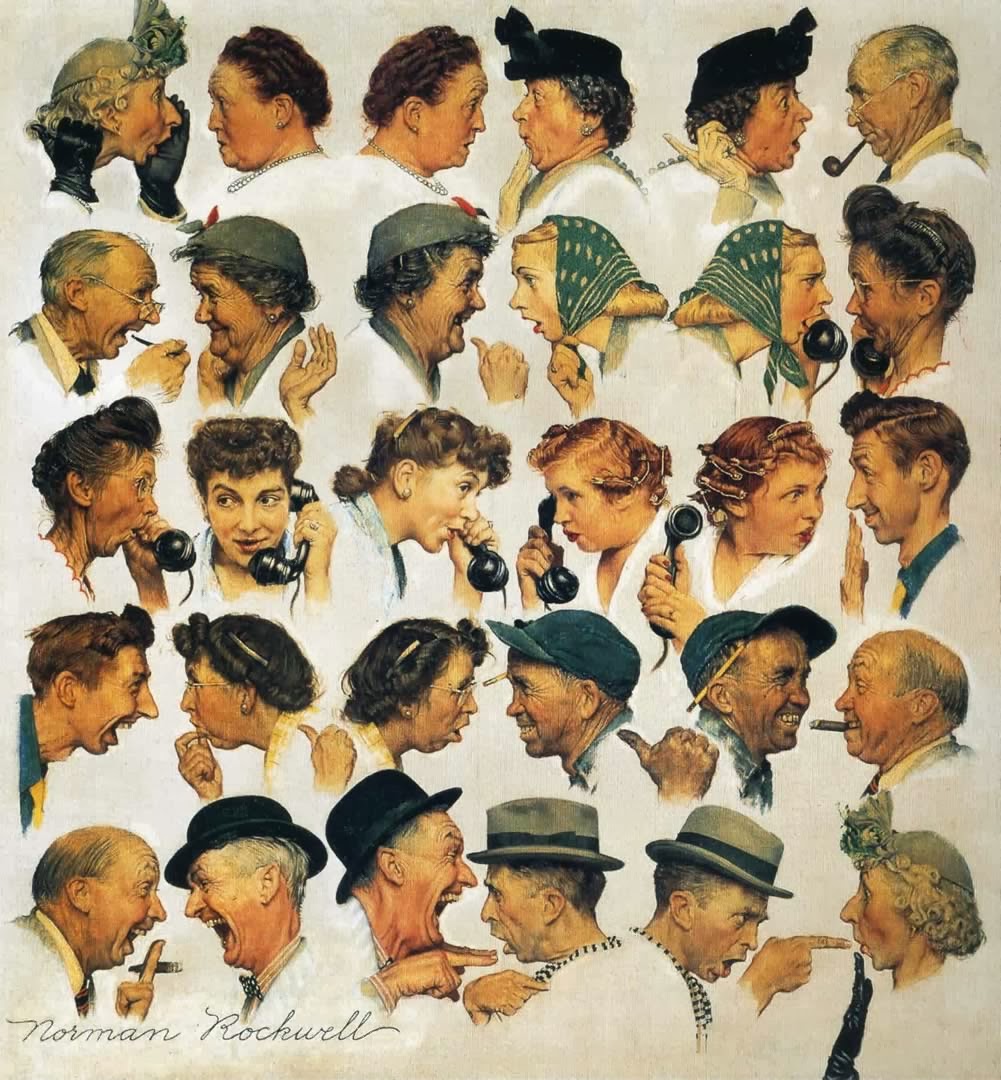

Something else to consider is the simple fact that, as big as the art world looks…everybody knows somebody. Illustrators know gallery painters who know comic artists who know film designers who know sculptors who know calligraphers who know educators who know toy makers who know gaming artists who all know art directors and publishers and producers and editors and collectors and gallery owners. And everybody talks. With conventions, trade shows, exhibits, and workshops going on all the time, your path will almost inevitably cross with that of someone you may have had a disagreement with at one point or another. Or their co-worker. Or their friend. “Ah, yes; so you’re the person that tweeted that my father slept with sheep. How nice to finally meet you at last…oh, and this is my brother, the IRS Agent.”

With that knowledge…would you prefer people be talking about how great your art is and what a pleasure it is to work with you…or would you rather have them gossiping about your fight with this company or that art director (which, regardless of the circumstances, almost invariably will leave many with the impression that you’re someone to avoid hiring)?

Pretty easy choice, isn’t it?

I’ve been working as an artist and art director for going on 40 years (I started when I was, uh, 2 *cough*) and have made my share of social missteps and shot my mouth off when perhaps I shouldn’t have: fortunately they didn’t happen on-line and morph into liabilities to drag around, much like Marley’s chains, years after the fact.

Recently I read an internet rant (which, as is the nature of the beast, went mildly viral) from a graphic novelist unhappy with his editor and, by extension, his publisher. Naturally, there were plenty of ignorant yahoos who immediately chimed in with enthusiastic denunciations of the company and, as it turned out, an editor who was not even remotely associated with the property and was merely a proxy target of the unhappy camper. This wasn’t a novice doing the complaining but an artist with a certain amount of success, recognition, and even a few major awards on his shelf. But instead of coming off sympathetically, instead of sounding like he was merely taking up for himself and “sticking it to The Man,” instead of “warning” his fellow artists about an “incompetent” business, instead getting what he may (or may not) have been seeking…he only succeeded in making himself look both petty and doltish. He made himself the source of idle gossip and, more seriously, told potential clients he might be an inconsiderate pain-in-the-butt to work with, one not worth the trouble. In the most boorish and public way, he advertised to the world that he was, despite all his credentials or abilities or awards…an amateur.

Now maybe this guy had every reason to be upset; maybe he had been chivvied or ignored or mistreated and had reached his boiling point. But to resort to airing his private business and pillorying innocent people on the internet? No matter how you slice it, that’s just bad form.

Part of being professional is knowing how to conduct yourself—and that applies to everyone, regardless of which side of the desk you’re sitting on. I’ve worked for great people and I’ve worked for mean-spirited asshats: the former I cultivated long-lasting relationships with, the latter I learned to avoid no matter how much they were willing to pay (and, yes, took delight at a distance in watching their eventual and inevitable comeuppance).

That’s not to say that when you’re wronged you have to bend over and take it; that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t fight back. That doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t blow off steam with buddies over beers about some client’s egregious behavior. What it does mean is to comport publicly with a level of dignity and discretion: in words and deeds treat your clients the way you wish to be treated. Which goes hand-in-hand with treating your business as a business: along with everything mentioned at the beginning of this post, get everything in writing, be proactive in communication, ask questions rather than assume, nurture trust and confidence, and, above all, resolve disagreements calmly, privately, and directly as soon as possible. People are people and most will try to fix problems or reach reasonable solutions when calmly given the opportunity.

And if there’s no resolution…there’s an attorney on every street corner. Waiting. Lawyering Up is always a last resort and should never be entered into lightly, but…businesses understand business and professionals settling their disputes via the services of other professionals is SOP. As long as it’s not frivolous, getting an attorney involved to resolve a dispute doesn’t automatically cause lasting ill-will and eliminate future work opportunities: I know a popular artist in Hollywood who sues his employers semi-regularly, sometimes while he’s in the middle of a job for them—and he has routinely been rehired by the same people for other projects that came along after they’d resolved their problems. Everybody understands and can respect someone defending their rights: it’s, as I said, business.

Fussing, insulting, and name-calling via social media is personal. Trying to shame the company you want to work for into giving you more jobs/money/opportunities only closes doors, not opens them. Being hammered via Twitter and Facebook can be hard for people to forgive. And…it’s unprofessional.

Your reputation is an important aspect of your “brand” that you need to manage as an asset and ultimately protect. “Being a pro,” being someone your clients can respect, trust, and, ultimately, enjoy knowing and working with, will go a long way toward ensuring a viable and lasting career.

Excellent post… applies to the music business as well…

You are a gentleman, a professional, and you look great for “42”.

Bravo

Excellent as always!

I think people rush to shout to the internet masses too quickly sometimes. I read a great quote about how if you give it time all feelings will pass. As a professional I know it is the best policy to relax and detach for a while until I am calm again and can make a rational decision. I once resisted the urge to tell a disrespectful client to eff off and in a day HE calmed down, saw the error of his ways and proceeded to pay my bills for several months. 🙂

This is a great post Arnie! Like DanHale just commented, people rush to the internet to air their grievances far too quickly. The masses are very quick to assume and almost never correctly in either parties favor.

Can I double-like this?

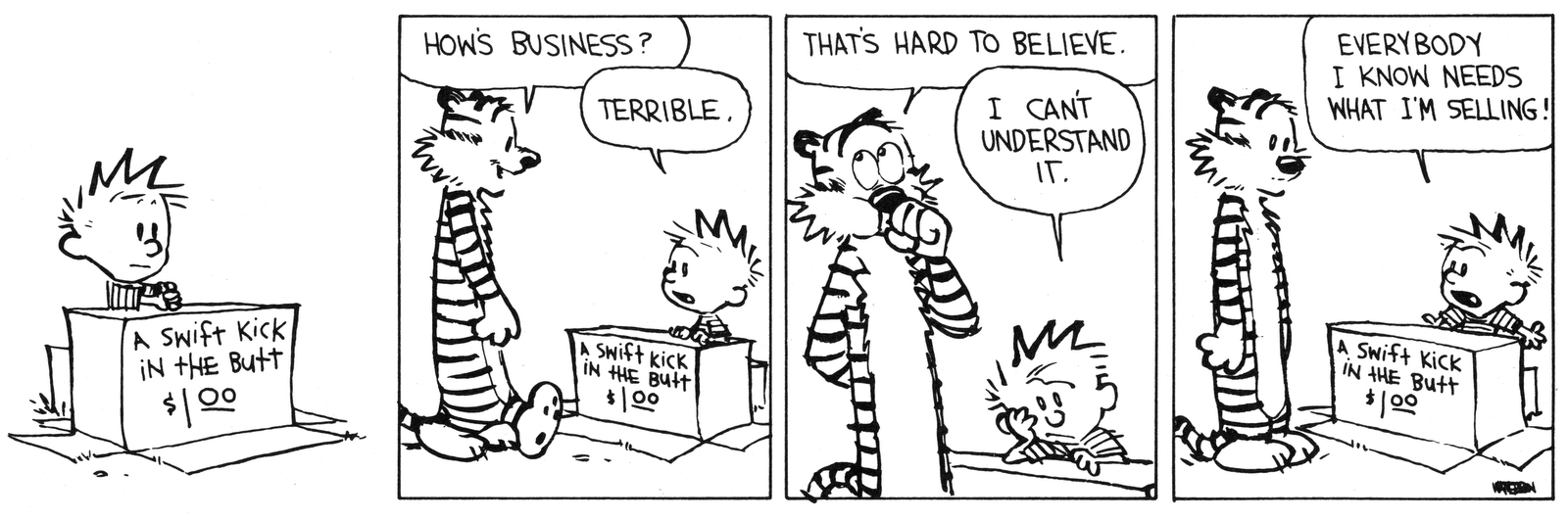

Great post! Looking forward to 2-4! Besides, any post that starts with Calvin and Hobbes is off to a really great start!

Wise words!

Excellent post. I'm looking forward to the next one in the series!