|

| Actual pixel crop from a recent reference shoot using a highres DSLR, fast prime lens, and studio strobes |

In talking with students and aspiring illustrators, I’ve been happy to see that shooting reference is becoming much more well understood as an important and widely used tool. That said, I’m still amazed at how many people will go to the trouble of finding and posing a model but still short change themselves with laziness and bad habits. Careless lighting may be the worst offender, but another common thread that gives me concerns is the phone camera.

Yes, I’m here again with yet another post about photography and illustration. What I want to look at specifically is: how big a deal is it really if you shoot reference with a phone rather than a conventional camera?

The Set-Up:

This is actually a subject that I’d been wanting to look at for quite awhile now, but it didn’t make sense until I upgraded my phone to a current, top selling model. As a Samsung Galaxy user since 1st generation, that means today’s comparison will be done with my new Galaxy S8. For the traditional camera, by contrast, it didn’t seem appropriate to use anything too recent or expensive. I gather a key reason that artists choose a phone camera in the first place is because something more professional is or seems out of the budget. By that standard, I decided to use the camera that I bought when I was just starting out, the 2006 released Canon Digital Rebel XTi with an old 18-55mm f3.5-5.6 kit lens. B&H has the same kit listed right now at $170, which seems about the going rate on eBay.

Samsung Galaxy S8 specs:

cost: $750

resolution: 12 megapixels

max aperture: f1.7

sensor size: 5.76 x 4.29mm

angle of view (35mm full frame equivalent): about 27mm, plus digital zoom

Canon Digital Rebel XTi with kit lens specs:

cost: $150-$200

resolution: 10.1 megapixels

max aperture: f3.5-5.6

sensor size: 22.2 x 14.8mm

angle of view (35mm full frame equivalent): 29-88mm

To test the two head to head, I had a model pose in both full body and portrait scenarios. Again taking limited budgets into account, I set up using only conventional lightbulbs instead of flash units (two 100w bulbs). This lighting was far from ideal, so we’re not going to see either of these devices performing at their best. The intention is more to see how they will perform in an improvised studio setting with cheap and easy lighting.

I also want to make a point to say this is not a sales pitch for either camera. They were chosen simply as general representatives of a current phone and outdated DSLR respectively.

My Expectations:

I think it’s possible that the Samsung will outperform the aging Canon in overall image quality (tonal range, color accuracy, etc.) as camera sensors have improved by leaps and bounds over the 11 years between these two devices’ releases. But it is worth considering how much smaller the sensor is in a phone vs a DSLR, and I wondered if newer tech can win out in what would otherwise be a solid disadvantage of size. The large f1.7 aperture will also allow the Samsung to do better in low light, allowing in between 4 and 16 times as much light as the Canon kit lens, which should mean lower, cleaner ISOs.

On the other hand, I’m very strongly expecting that the optical zoom on the Canon (or more specifically, not being restricted to only wide angle) would make up for any outdated tech or slow optics when it comes down to practicality.

Though I would also give a DSLR an edge for processing flexibility thanks to shooting raw files, the Galaxy S8 is among a handful of more photographer friendly smartphones that features that option as well if you shoot in “pro” mode and enable raw+jpg. For this comparison it really ought to be a draw. The Samsung also puts out images about 20% larger, though that’s mostly accounted for in the wider 3:4 image ratio (vs 2:3) and, again, shouldn’t really make much real world difference.

Results:

|

| Canon (left) zoomed to a “normal” view and Samsung (right) with the default wide angle |

Distortion:

This was the primary concern that I had about a phone camera, and the most often cited reason why people are dubious of artists using photo reference in the first place. All lenses “distort” to some degree, in the sense that no camera lens can see the world in the same way as the human eye and brain. All are imperfect in some way (which is fine because my actual astigmatic eyes are also decidedly imperfect). The important thing is understanding, anticipating, and making use of that distortion.

I’ve written in the past on how you can think of painting is terms of wide angle, normal, and telephoto scenes. If you plan to shoot your reference with an appropriate angle lens and place yourself an appropriate distance from your model, you will be letting the natural spacial distortion of the photo reference properly inform your painting. Distortion looks fine as long as it is consistent throughout the image. It’s more or less the same as making sure that your light sources are consistent and you don’t have conflicting lighting inside of an image.

Why does this make phone cameras at a disadvantage for shooting reference? Because they only have one angle of view* and it is decidedly in the wide angle category. This is great for shooting groups of people and/or shooting in small spaces, which is what they’re mostly expected to be used for. The angle of view on a phone seems about what we see with a good bit of peripheral vision included. When it comes to shooting a single figure or portrait, however, you begin running into problems.

|

| Spacial distortion in wide angle lenses becomes very obvious in portraits and close-ups. Again, Canon left and Samsung right. |

The closer that you stand to your model, the closer it will feel that the viewer is to the model. With a wide angle lens, you need to get pretty close to fill the frame, especially with a portrait. The result is spacial distortion that only looks natural if the scene supports that we as viewers are uncomfortably close. Otherwise, the distortion is as out of place as a top lit figure standing next to a side lit figure.

The DSLR, however, is designed to allow changable lenses. In the examples here, I’m using a “standard” zoom that moves from wide angle to short telephoto. A phone can “zoom” as well, but it is doing so digitally. This means it is enlarging a portion of the photo by cropping and upscaling, similar to enlarging a lowres image off the web. The result is degraded image quality. Since the DSLR zoom is created by physically moving lenses, the image quality does not degrade. This means I can stand further away from the model and still fill the frame. In this way, I get the distance needed for natural looking shots without sacrificing detail or sharpness.

I imagined this to be the biggest issue and, in actually practice, I definitely feel the fixed wide angle of a phone is far and away the biggest concern. There are attachments designed to convert a phone lens into a longer focal length, but I’m not aware of any that don’t just swap compression issues for poor optical quality.

Image quality:

This was what had me most curious and, at a first glance, I was ready to simply eviscerate the Galaxy S8 on image quality. When it comes to camera sensors (where the image is actually captured), bigger is usually better. So the question was, do the years of advancements make up for the miniature size when comparing a new (small sensor) phone to an old (big sensor) DSLR.

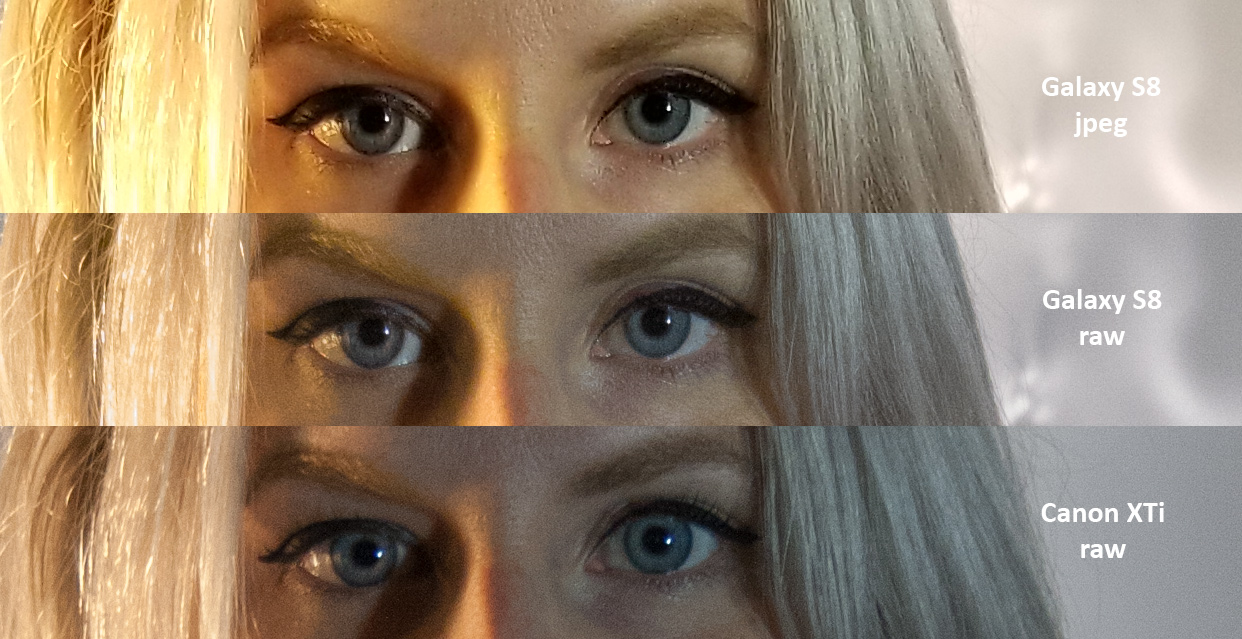

The sensor of the Canon is around 13x the surface area of the Samsung. That means, with similar output resolution, the Samsung is squeezing 13x as much information into it’s tiny sensor on an inch-for-inch comparison. In addition, phones have not traditionally supported shooting in raw format, which is a compression free camera file which I strongly recommend using if you are not already. On comparing the Samsung jpegs vs the Canon raw, it was looking very bad for the Samsung.

HOWEVER. The Galaxy S8, along with a handful of other recent smartphones, does save raw photo files if you tell it to, and this was where I found the most surprising results. I’ve read that there are also 3rd party apps which enable saving raw files if your device does not give that option.

|

| Fine tuning exposure in Lightroom allows me to extract more information from highlights and shadows, in addition to a number of other very useful tools |

Jpeg files are more limited in post-processing than raw files because they discard information that the camera thinks you won’t need. With processing software like Adobe Camera Raw or Adobe Lightroom, that extra info can be used to fine tune color and achieve a broader, more even tonal range. This is normally the main reason that I recommend shooting raw, however the surprise was just how much compression and funky internal processing the Samsung was also adding to jpeg images, probably to get results that look really punchy at web resolution with bargain rate file sizes. Printed out, however, the contrast felt harsh and the detail rendered was, well, underwhelming. Some areas going gooey from compression and others looking over-sharpened through the phone’s software. These files were generated in parallel to the the raw from the same single shot, the only difference was how the phone was saving them. When working with the raw Samsung files, image quality was, by comparison, remarkable.

|

| Actual pixel comparisons |

Meanwhile the Canon, hindered by the slow kit lens, did struggle to get enough light for a usable shutter speed, especially considering the now almost laughable top ISO of 1600 (and top of range ISO is usually best avoided if possible). With the lighting I had on hand, I had to make some compromises. The final settings for the Canon ended up being ISO 800, 1/50th of a second exposure, and f5.6 aperture. A faster lens would definitely have been a help. Still, even pushing the ISO for such an old model, results were certainly adequate. Head to head, the raw unzoomed Galaxy S8 takes it for me with cleaner microcontrast detail, though the Canon does have the potential for improvement through a lens upgrade if budget allowed.

As mentioned briefly above, zooming in with the Samsung in order to correct the distortion issues led to a heavily compromised image quality. In the default jpeg mode, I can only describe it as “VHS-esque.” Another surprise though, shooting in raw and then cropping and upsizing with Photoshop (the raw file records the full field of view even when zoomed in, so you have to manually crop and enlarge to get the zoom effect) actually did limit the damage noticeably. It should be noted though, I was only zoomed to about half the digital range here and the output I ended up with was reduced from 12 megapixels to just around 1.5 megapixels before scaling back up.

I want to state that again for emphasis, as it may be the most important point in this article to understand: In digitally zooming to correct the wide angle distortion, which I personally feel is critical, my 12 megapixel phone was only able to produce a 1.5 megapixel image at true resolution.

|

| Actual pixel comparisons |

My final verdict was a bit mixed, but not entirely in the way I’d been expecting. The Galaxy S8 is capable of impressive quality that rivals a larger but long-in-the-tooth camera like the XTi. Again, capable of. If you only use the default auto settings though, you’re giving all that away. But the real issue for the smartphone continues to come down to the forced wide angle. This one issue alone decides it for me, particularly as the modular nature of a DSLR (or other changeable lens camera system) allows one to improve in pieces over time as budget allows. It is nice to see that zoomed in raw images from a smartphone are as good as they are, but it still falls quite short of the cheapest possible normal or portrait lens when shooting those angles, which accounts for about 90% of my own reference shoots.

In the end, you know how much image fidelity you want: either “more” or “no opinion.” If your work doesn’t demand detail or you can do without the subtleties, and I’m aware that describes many artists whose work I really admire, you certainly can work with what’s already in your pocket. For the work that I aim to do, however, I do better with better.

I believe it was the marketing brains at Apple who popularized the wisdom that the best camera is the one you have with you. I certainly won’t argue that. But if detail matters to you at all, I’m of the opinion that a purposefully chosen tool will still serve you best, even if it’s been collecting eBay dust for the past decade

I love these articles so much.

Thanks Sam!

Adobe Lightroom Mobile will allow you to shoot RAW (DNG) on your mobile phone. I used it a couple weeks ago to do a cover portrait for a client, as a (very) last minute request. Worth playing with, if you have the time or inclination.

Awesome tip, thank you! It's really cool to see developers making this option more available