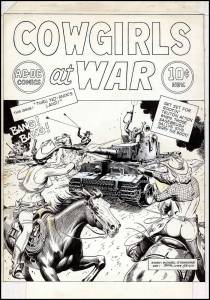

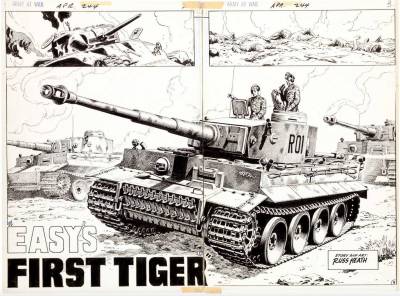

Last month Russ Heath, one of my childhood inspirations for becoming an artist, passed away at the age of 91. Working in virtually every genre for all of the major comics publishers (though National/DC seemed to be his primary home from the 1960s through the ’80s) there was always a lot to love in his stories. A meticulous craftsman who also had an excellent sense of drama, Heath became best known for his highly-detailed war comics and drew numerous one-off adventures as well as had lengthy runs illustrating—and sometimes writing, too—the “Haunted Tank” (which he co-created with Robert Kanigher) and “Sgt. Rock” series. As a humorist he also contributed to the 1960s short-lived Trump Magazine, Playboy (assisting on “Little Annie Fanny”), and National Lampoon. Heath was something of an unheralded workhorse for the comics field, the widely-respected go-to guy who, conversely, was often under-appreciated by fans because he did very few superhero stories. And like most under-appreciated workhorses, Russ, unfortunately, often struggled to make ends meet, particularly later in life. Oh, sure, he got awards—an Inkpot, induction into the Will Eisner Hall of Fame, etc.—but when people talked about comics creators Jack Kirby or Steve Ditko or Jim Lee or Alex Ross were some of the artists getting the buzz, not Russ Heath.

Someone who had paid close attention to Heath, though, was Pop-Artist Roy Lichtenstein.

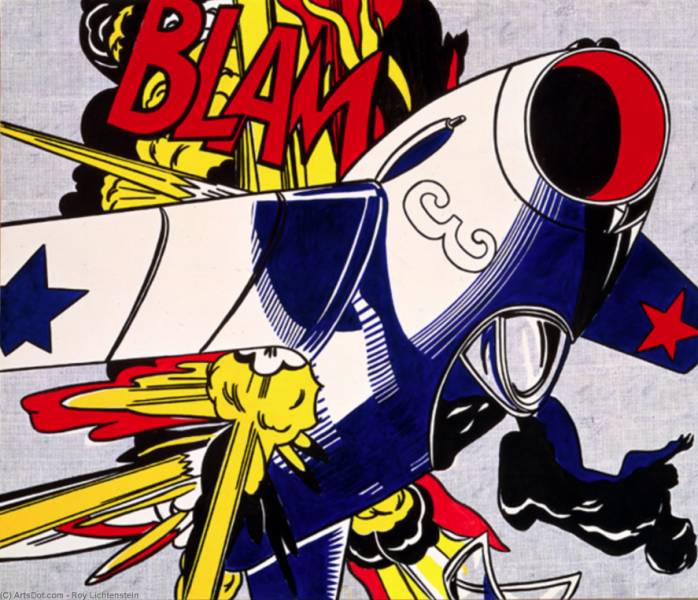

“WHAAM!” by Roy Lichtenstein is based on several different comics panels by Heath, Irv Novick, and Jerry Grandenetti.

Whether you want to call it “transforming” or “reinterpreting” or “swiping” probably is a matter of perspective, I suppose, but Lichtenstein unquestionably “sampled” panels from several of Russ’ comics without acknowledgment or compensation to create the paintings “WHAAM!”, “Blam”, “Okay Hot-Shot, Okay!”, “Brattata”—all of which went on to sell for many millions of dollars and reside in major collections or museums around the world. (Work by other comics artists also were resources for Lichtenstein’s paintings as detailed here.)

As the New York Times said in their obituary for Russ, “The art world has long debated whether Lichtenstein, who died in 1997, and other artists who worked in this way were creating art or merely copying it. Aficionados of comic book art, who have always felt that the work they love has not gotten the proper respect, are especially defensive of Mr. Heath and others whose drawings were borrowed; admirers of Lichtenstein say he altered and elevated the source material to transform it into an artistic statement. The art critic Tom Lubbock was one who thought that Mr. Heath and others deserved more credit. ‘The cartoon artists, though highly productive, were not naïve, anonymous hacks,’ he wrote in 2004, reviewing a Lichtenstein retrospective at the Hayward Gallery in London for The Independent. ‘A lot of the innovations in Lichtenstein’s pictures are innovations that they came up with first. They were responsible for adapting the convention of the cinematic close-up to the still image. They worked out the dynamic interaction of image, caption, speech bubble and sound effect. They devised those dramatic compositions from which Lichtenstein’s work gets much of its impact. These illustrators, it seems to me, should be co-credited (alongside Lichtenstein) with the paintings to which they made such decisive though involuntary contributions.’”

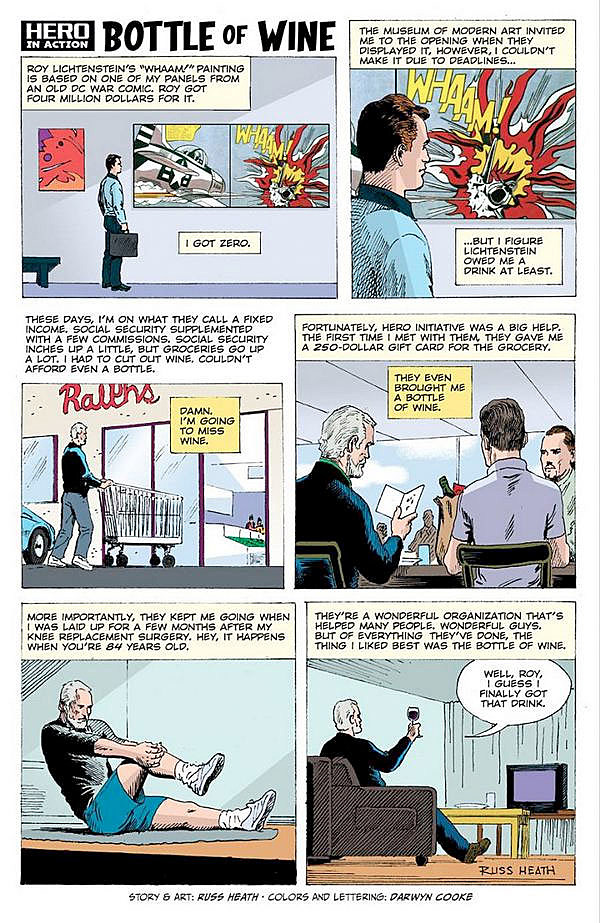

And years later what did Heath make of the appropriations? Well, as was his nature, he commented in a comic strip.

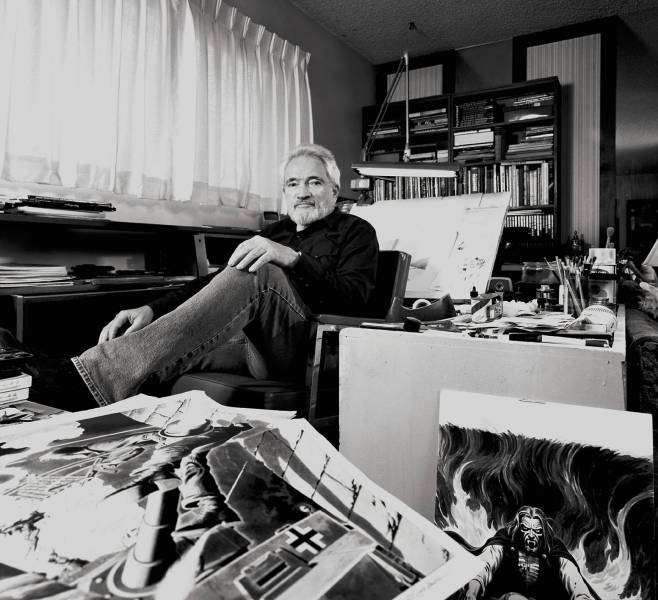

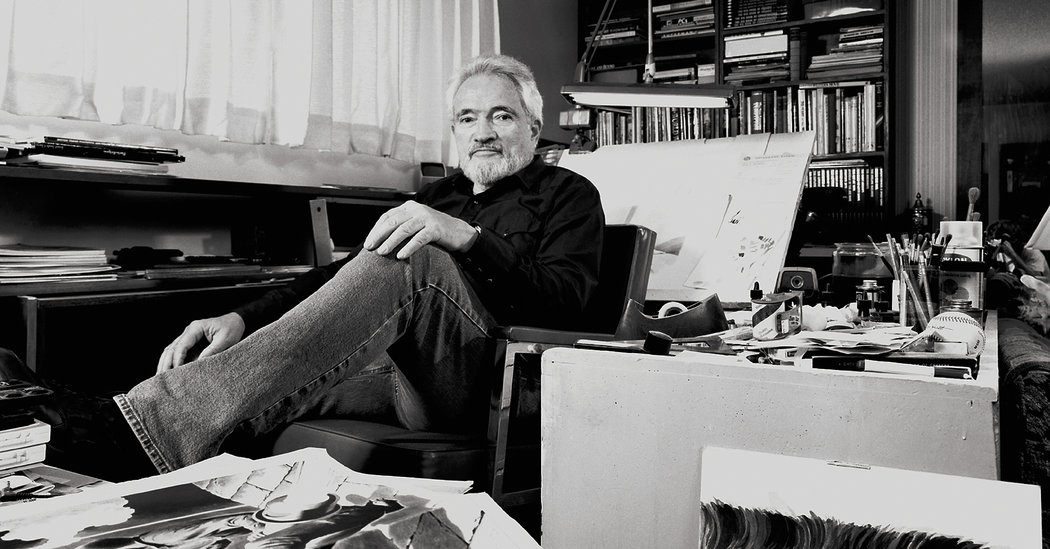

Russ Heath in his studio photographed by Greg Preston.

Lichtenstein once said “I am nominally copying, but I am really restating the copied thing in other terms. In doing that, the original acquires a totally different texture. It isn’t thick or thin brushstrokes, it’s dots and flat colours and unyielding lines.” And critics, with exceptions (as noted in the Times), often agreed, insisting that his works transformed his sources in a number of subtle but crucial ways and on occasion have claimed that the lack of acknowledgment was a further reflection of—or commentary on—the way comics publishers of the day often denied their creators credit for their work. (Which seems like something of a far-reaching specious excuse, if you ask me.) As with all things in the art world, the rightness or wrongness of how something is created or what constitutes “Art” is and will probably always be open to debate. But what do I think? Well…the comics, particularly for the WWII generation, were the cultural touchstone that Lichtenstein capitalized on, exploited, and ultimately profited from. Though isolating, enlarging, and repainting a single panel may well have been transformative and provided an entirely different perspective, meaning or social commentary the resulting paintings could not have existed without their resources and the public’s general familiarity with the comics medium. So, sure, I think at least at the very minimum an acknowledgment of Heath, Novick, and all of the other comics artists would have been appropriate on Lichtenstein’s part; it didn’t happen while he was alive, but his foundation now mentions the resources for at least some of his comics-based paintings.

I’ll also say this…

I love Russ Heath. I always have, I always will—and some of the reasons why are posted below. If, in 50 or 100 years, people are still talking about him because of Roy Lichtenstein’s sampling…well, maybe that’s a good thing and will prompt others to seek out Russ’ art and give him the attention he deserves.

Russ Heath was an incredible artist! Thanks for this post Arnie, I did not know about his death. I particularly liked his black and white work for Warren Publications, which were exceptionally well done.

It is good that the New York Times article gave Heath accolades, and brought up the shameful Lichtenstein ripoffs. The public needs to be reminded about Lichtenstein’s M.O. It is well documented how Lichtenstein “appropriated” other artists work over and over again. For some reason those derivative works were elevated as great modern art, selling for millions, while a far superior artist like Russ Heath winds up a pauper. Sickening!

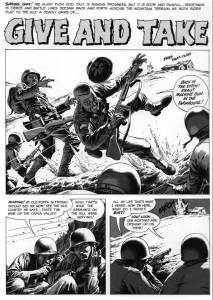

Thanks, Joel. I, too, am a big fan of his Warren comics, particularly of his one BLAZING COMBAT story “Give and Take” which is included here. I never got to meet Russ, but boy did he have an effect on me.

Mark Evanier tells this funny story about when Russ was called in to assist on a “Little Annie Fanny” strip: “One time when deadlines were nearing meltdown, Harvey Kurtzman called Heath in to assist in a marathon work session at the Playboy Mansion in Chicago. Russ flew in and was given a room there, and spent many days aiding Kurtzman and artist Will Elder in getting one installment done of the strip. When it was completed, Kurtzman and Elder left…but Heath just stayed. And stayed. And stayed some more. He had a free room as well as free meals whenever he wanted them from Hef’s 24-hour kitchen…so he thought, ‘Why leave?’ He decided to live there until someone told him to get out…and for months, no one did. Everyone just kind of assumed he belonged there. It took quite a while before someone realized he didn’t and threw him and his drawing table out.” 🙂

This is a great article. Mr. Heath’s art was and is so phenomenal. I spent about 11 years as a chef. One of my greatest lessons is that if someone says they’re about to “elevate” something it just means they’re going to rip it off without any respect to its source haha.

Thanks, Zac. And I always have tended to equate someone talking about “elevating” something with pretension. Any art for any genre or venue done with care and honesty deserves respect all on it’s own. 🙂

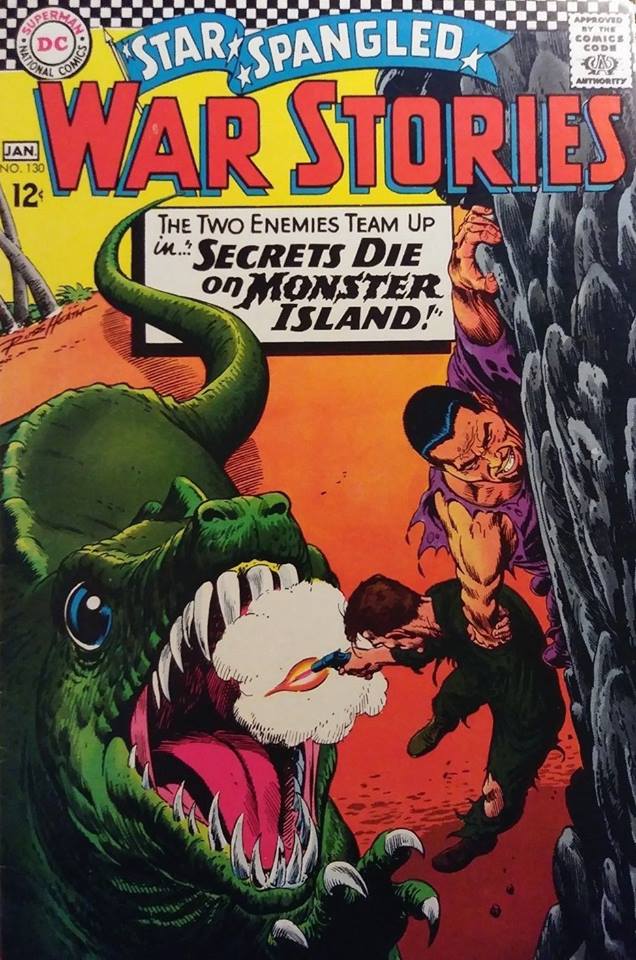

Thanks for the article, Arnie. Since superheroes never really grabbed me as a kid, I grew up seeing lots of Russ’s art in the war comics I loved. His stories of dinosaurs vs. G. I.s in Star Spangled War Stories’ The War that Time Forgot were a favorite. Russ didn’t have the anatomical accuracy in his beasties of say William Stout but he drew some amazing critters none the less. I also really enjoyed his work on The Haunted Tank and had not realized that Russ was the cocreator of that title. He will be missed.

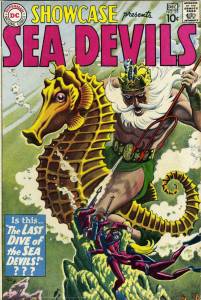

Thanks, Aaron. Yeah, I think Russ either based his dinosaurs on previous artists’ interpretations (much like Frazetta, Williamson, Krenkel and others did) or made them up, but they were always pretty exciting. Besides The Haunted Tank, Russ was also the co-creator of The Sea Devils.

Boy these are tough questions, but one possible route Lichtenstein could’ve taken was to contact the artists beforehand and discuss it with them. Chances are many would just like to have been asked. I did as much once, asking a cartoonist if I could paste a few of his characters into a panel of one of my toons. He was fine with it.

Hey, good post. Just had a “Russ Heath’s birthday” post cross my thread (Sept. 29) and got thinking about Roy vs. Russ.

Thanks for sharing. I’m a superhero/horror comic guy — war comics weren’t my thing. but always loved Heath’s work. It’s no wonder Heath’s work ended up in so many other artists’ swipe files.

I have loved Heath’s work since I first saw it in a DC comcis around 1972. But…!

You wrote:

“…the paintings “WHAAM!”, “Blam”, “Okay Hot-Shot, Okay!”, “Brattata”—all of which went on to sell for many millions of dollars and reside in major collections or museums around the world.”

This not correct.

‘Whaam!’ was sold by an art dealer to the Tate gallery in London in the 1960s for about 10,000.00 dollars (5,000 pounds) at the then current dollar value. She had bought it in New York from a gallery show in 1963 for maybe 2,500- 3,500 dollars, exact amount not known. Roy Lichtenstein would have got most of that and the gallery maybe 20%.

Only one small bit of ‘Whaam!’ is based on a Heath panel; the plane being blown up.

That’s why Heath’s comic strip originally started with him looking at the painting ‘Blam’, which was wholly taken from one of his panels.

Blam’s selling price is know: 1,000 dollars.

Anyone spreading this untrue comic strip around the internet, or simply reading it, should be aware of the facts. And that includes the change of Blam to Whaaam! in the strip which was done for… who knows what reason? Because Whaam! is more famous?

The “4 million” is still a lie, either way.

I just saw your comment, Guy. I stand 100% by my comment, re “…the paintings “WHAAM!”, “Blam”, “Okay Hot-Shot, Okay!”, “Brattata”—all of which went on to sell for many millions of dollars and reside in major collections or museums around the world.” I didn’t say Lichtenstein got the millions for those particular sales—and the original sale prices to collectors aren’t relevant—but only that they HAVE generated those sums over time and are parts of major museum collections around the world. And, of course, Lichtenstein did indeed earn many millions of dollars from the sale of his paintings and prints in his lifetime (he died in 1997) so he always made out pretty well.

As for Russ’ comment in the first panel of his strip…so he made a mistake in thinking that Roy got the $4million for that particular painting. Somebody got it or something close and it’s a pretty innocent mistake. But the irrefutable fact is that the person who didn’t get anything for “WHAAM!”, “Blam”, “Okay Hot-Shot, Okay!”, and “Brattata” was Russ Heath. Or Irv Novick. Or Jerry Grandenetti.