I’ve always found that writing the first few lines of anything—essay, introduction, blog post, whatever—is the hardest. At least for me. That’s why I’m going to skip the preamble this time and plunge head-first into another batch of kinda-sorta-they-are-if-you-want-them-to-be-but-not-if-you-don’t “rules.”

Draw

Everything. All the time. Wherever you are. If you are (or have been) lucky enough to have Bill Carman or Jon Foster or Chris Payne or any number of other top-tier instructors at school you’ve already heard this advice and know the drill. If not… Have a small sketchbook with you to scribble in: you never know when or where inspiration may strike. Draw from life; draw from photos; draw with references and without, but for goodness’ sake, d-r-a-w! The only way to draw hands or feet or drapery or facial expressions or animals with authority is to repeatedly practice drawing them. Perhaps the most inspirational segment in the documentary Crumb—no, not the part where he talks the woman into giving him a piggyback ride during his gallery opening—was watching him sit on a bench on the street or in a restaurant while he drew the people passing by. Drawing what’s real will help you to draw what’s not real convincingly.

Keep a Record

Your art is more than art: it’s your asset. It’s your business. And, yes, your art is part of your legacy. It goes without saying that you should keep concise files containing contracts, invoices, receipts, correspondence, etc.: that’s all common sense. But you’d be surprised at how many artists don’t have a complete archive of their own work—and that, in the long run, costs them moo-la. John Jude happily points out that he’s made significantly more in licensing fees for one of his book covers than he was originally paid to paint it in the first place. You can’t sell reprint rights or license images if you can’t deliver repro materials to your client. It used to be that transparencies were the only way to go—cheap was about $40 a pop—but they could be a challenge to keep track of and clients were (and still are) notorious for not returning them. Now days with any number of inexpensive ways to digitally archive and deliver art, there really isn’t any excuse not to do so. The most frustrating part of doing the four books with the Frazettas was that Ellie would sell originals or Frank would paint over older works without ever making a copy. Not a slide, not a tranny, not a scan: the works were gone along with the opportunity to license the art and make it continue to earn money for them. I can’t count the number of times prospective clients tried to license one painting or another from them without success because the art no longer existed or wasn’t in their possession and there was no record of it. Without a proper archive it also made it difficult to answer historical questions or keep track of who controlled the rights to what. Don’t fall into the same trap: a properly maintained record/archive will pay off in many ways in the future.

Imitating Isn’t the Same As Being “Influenced”

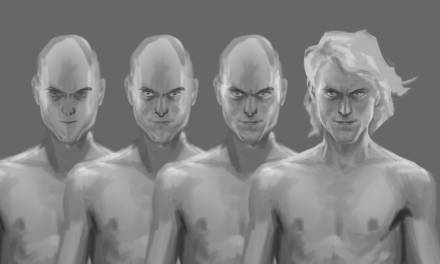

Everybody starts out copying the artists that inspire them: it’s a natural rite of passage. But at some point an artist has to stop copying or imitating and find their own voice, their own approach, if they want to break away from the pack. You can find inspiration from any number of sources, but ultimately the solution to the “problem,” the approach you take to the picture, has to be uniquely yours. No one can own a style or technique or idea, but it’s what you do with the style, technique, or idea that sets your work apart. Your influences should go into a psychological blender and what comes out on the canvas or through the computer should be a reflection of you, of who you are, not a version of someone else. You definitely do not want an audience (or critics or art directors) to look at your work and only see your influences, not you.

There Is No Magic Wand

There is not a mystical tool which, once acquired or mastered, will turn you into an Artiste. Neither the paint nor the computer can do it for you: it’s your skills, your outlook, your intellect that creates art. I’ve seen stacks of great paintings and crappy paintings; I’ve seen equal numbers of great digital art and crappy digital art. If you cannot draw, if you do not understand color or composition or anatomy or perspective, if you don’t understand people and connect with them and know what excites them and frightens them and lifts them up and makes them sad…you’re not going to be able to create anything of significance, anything that will resonate, anything that will last, regardless of the medium you use. Being devoted to your craft is imperative, but it is also absolutely true that a real artist is curious about—rather than dismissive of—approaches and sensibilities different from their own. There is no “right way,” no “only way,” to create art. The tool does not matter: what the artist does with the tool is the only thing that counts. Painters are not “better” than photographers who are not “better” than sculptors who are not “better” than digital artists who are not “better” than watercolorists who or not “better” than… It’s all akin to Ford owners squaring off with Chevy owners or Marvel fans insisting that the Hulk is stronger than DC’s Superman: it’s silly. As a commentator mentioned in the Digital Vs Traditional thread, who in their right mind would say that Ansel Adams wasn’t an artist? Or Herb Ritts or Robert Mapplethorpe? Who would say that Stephan Martiniere or Andrew Jones aren’t artists of the first rank because the computer screen is their canvas? Take it another step: who would say that Watterson or Elder or Davis aren’t artists because they’re “merely” cartoonists? Not me. Or who would say that Berkey or Berry or Rayyan or Brom aren’t “real” artists because they work in genre? Nobody I can think of. Getting wrapped up in the tool employed or believing that it’s the tool that’s doing the creating is…dumb. It doesn’t matter how the artist “gets there” or what they use along the way…as long as they get there.

Be a Flirt, Not a Tramp

Ahh, the siren call of the internet. Many artists feel the need to put great big honking scans of everything they do up on their (or other) websites, ostensibly to promote their work. Web visitors happily copy these files and print or share (or, in extreme cases, bootleg) whatever they want. They love it. They appreciate it. But they don’t want to pay for it. And once people get used to getting something for free they resist forking over dough when the tap is turned off. In the meantime you’re left trying to figure out why everyone likes your work but aren’t willing to help you make a living doing it. Let’s face it, popularity means very little when it comes time to pay the rent and the bank account is empty. Plus, familiarity can lead to indifference. If your audience has seen everything they can tend to take you for granted: why should they buy your book or your prints if they’ve printed out (or loaded on their hard drives) everything they liked already? For nothing. Marketing dictates teasing your audience a bit; intrigue them without giving everything away. Make them want more. Flirt, but only let serious suitors get to second base. And when it comes to using your website to promote yourself to art directors/clients, trust me: if an art director can’t get a handle on what you can do with a few samples of your best work they’re not a very good art director (and yes, just because someone has a title doesn’t automatically make them good at their job). If one or two paintings of a dragon doesn’t convince them you can paint a dragon, 20 dragon paintings won’t either. Update regularly, but when you do, replace older works.

Be Honest With Yourself

Your mom thinks you’re Michelangelo. Your boyfriend or girlfriend thinks you’re the next James Jean. That doesn’t exactly mean you really are. Some years back I was at one of the few conventions that Thomas Blackshear exhibited at—and believe me when I say that Tom’s originals are astonishing and his sketchbooks are some of the most breathtaking I’ve ever seen—and there was an illustrator set up next to him that had been doing some interior drawings for several SF fiction digests. This artist had a couple of adoring fans surrounding him, telling him how wonderful his work was, especially in comparison to this “unknown” (meaning Blackshear) that was set up beside him…and, of course, it wasn’t. In fact, the guy’s art was, to be honest, pretty amateurish (which fit in nicely with the digests he was working for and the low wages they were paying). But his admirers couldn’t tell the difference—and neither could the guy, who basked in the compliments of a handful of fans and falsely believed (as revealed in the comments he was making) that he and Thomas’ abilities were equal. He was lying to himself: he did not have a realistic view of his own skills—which also meant that it was highly unlikely that he was going to keep learning and trying to improve. And…he didn’t. Where is he now? Forgotten. Unknown. Smile and take compliments graciously when they’re offered, but at the end of the day be your own worst critic—without devolving into beating yourself up when something doesn’t turn out or, on the flip side, being unable to recognize your success when it does. Everyone has their share of failures and triumphs: keep things in perspective and be able to distinguish one from the other. Always know what you can do and what you can’t—refine what you do well and in recognizing what you can’t do, study and practice to try to improve and overcome your weaknesses. Mom will always love you, good, bad, or ugly. The marketplace isn’t as compassionate.

Extremely inspiring, Arnie! Thanks for the uplifting words of wisdom 😉 On that note, time to draw and get to my warm ups for the day…

I love you Arnie. Why didn't I run into you 15years ago? Things would have been so much easier.

I will post this link to every up comming artist I know.

The last one was the best, along with Be a Flirt. I have my little sketchbook resting here with me, after a morning(sketching) walk 🙂

I especially like your comments about “Be a Flirt, Not a Tramp”. I visit a lot of websites where it seems the artist posts new work just simply because it's new, without considering whether it showcases the best of their ability and belongs in their portfolio. Everything on your site is just that…. your portfolio.

Tell you what Arnie, between you and guys like Jon over at Art Order I could just sit back in an armchair at home. I'll just send my students to a few select places and I can sit back and watch reality tv. This is great stuff. Thanks!

That was good! I am guilty of more than a couple of thumb breaks, I may have turned red a few times in the reading. Gotta go now and weed my web site 🙂

Thank you Arnie.

Jon

Great thoughts. Seems a bit of life wisdom in all that.Thanks Arnie.

Thanks for the wise advice Arnie 🙂

As a rookie illustrator (just starting out at the tender age of 48), I appreciate the advice.

Thank you for this, Arnie. Priceless.

Oh please, oh please keep this blog going. I promise to save up the money to join the Visual Lit Program next year (going to sell a kidney, or a spleen, who needs a spleen anyway?) but for now I need all the amazing advice and awe-inspiring access to talent that I can find.I live in South Africa and where I'm from an education in illustration is a truly foreign concept. Jon Foster is my illustrative hero and all of you have so much to offer us minions. The fact that you have taken the time to dole out this priceless wisdom for free, says great things about you. Thank you, thank you, thank you.

Awesome post, much obliged.

Golden! Thanks Arnie, I feel terrible in so many ways when I read through this. Lesson learned. I am glad that all of you have put this blog together. It's been a great learning experience.

Great insights, especially about how rules evolve over time and aren’t always one-size-fits-all. It reminded me of how in gaming, especially with older PC titles, understanding the “unwritten rules” can make or break your experience. I recently explored some classic games through a site that provides highly compressed versions — it’s been nostalgic to revisit those titles without needing huge downloads. Posts like this really show how rules (new or old) still shape our digital habits.