by Petar Meseldžija

Paja Jovanović is one of the greatest Serbian painters. Uroš Predić, another great painter, is perhaps the only artist from the Serbian art Pantheon, who can match, to a certain degree, Paja Jovanović in terms of the technical excellence and the impact of his paintings on the Serbian people and their culture. (I will write about Uroš Predić in the near future).

Paja Jovanović was a greatly talented, virtuous painter, nationally and internationally very successful, rich, praised and adored, although later in his life his art was criticized and dismissed by some of the 20th century art critics as outdated, dry, staged, detached from real life and a sterile example of the Academic Realism. Whatever the point of view of the scholarly art establishment, the fact is that his art was loved by the people. It has been said that, during a certain period, there was almost no Serbian home that did not have a reproduction on the wall of one of Jovanović’s famous pictures. (Nowadays the situation is quite different…)

In his long and prolific life, Paja Jovanovic created a large number of paintings, and although he also gained popularity as the remarkable portraitist, immortalizing many kings and queens, the politicians, the wealthy people and the artists, he is after all best known for his genre-compositions and works with the historical content. Although classified as the works of the Academic Realism, these depictions of the important moments from the national history, and the representations of the folkways, give more or less idealized, almost romantic, view of the history and the reality of life in the Balkans during the second part of the 19th century. Never the less, these images had a great appeal to the people of his time (they still do, as you will probably see for yourself while looking at the pictures below), and rooted themselves deeply within the national psyche. In a way they represented the powerful symbols of iconic, almost epic proportions, offering the guidelines to the national spirit that was, in those days, seeking its visual manifestation.

Wounded Montenegrin, 1882 (Paja Jovanovic was still a student of 22 in Vienna when he painted this painting, his first master piece)

However idealized, or unrealistic these images might appear, I think they should primarily be seen as the works of art, often technically brilliant, that deals with symbols and archetypes. As we know, the symbols are never meant to be the accurate historic, or journalistic accounts of the specific moments in time and space. Their function is rather to embody a certain universal idea, or the unifying aspects, and to communicate them to the consciousness in a way that enables the emotional and spiritual recognition and acceptance of their message. Many of Jovanović’s paintings, and their subsequent history, show how powerful and evocative these symbols can be.

However important or crucial to life, or to society, when taken out of the right context, all things tend to become less relevant; they lose their power and meaning. Therefore, my strong conviction, especially when it comes to less exact, or less “measurable” aspects of Life, like Art, is that it is outermost important to see things within the right context. When it comes to judging the artistic achievements of Paja Jovanović, this was apparently a difficult task during the 20sth century because of the dominion of the Modernistic Dogma, among a few other things, like politics, etc.. Nowadays, after being freed from its possessive and mighty grip, the world of art, and the art loving public in particular, is again allowed to enjoy and rediscover the forgotten qualities of until relatively recently despised forms of art like the Academic Realism, and alike. The fact that a serious, full scale monograph about life and work of Paja Jovanović has been published in Serbia just two years ago, more than 50 years after his death, is an example of the impact of the various dogmas on the way many people saw his art. The good thing is that there are now two Paja Jovanović books in the bookstores; one written by Nikola Kusovac and published by Belgrade City Museum (text is in Serbian, with only the summary in English); the other being published by “Radionica duše” and edited by Momčilo Moša Todorović (text in Serbian and English).

In spite of all the criticism, whether justified or unjustified, that the work of Paja Jovanović had to endure during the 20th century, and having in mind his remarkable and important position in the Serbian art and culture, he definitely deserves these monographs. As Mr. Kusovac stated in his book abuot Paja Jovanović: “…Still, no Serbian painter, before or after Paja Jovanović, has ever influenced the fine arts education, culture and, most of all, the patriotism of his people to such extend and so powerfully…”

|

| Decorating of the Bride, 1886 |

Alas, when I was an art student in the eighties, there was no book full of glorious images of Paja Jovanović’s art. Therefore I often used to visit the museums to analyze and to try to reveal the secrets of his paintings, or better said a limited number of them that I had access to. I must say that, in those days, it was not very popular for an art student to be interested in such an art, and to seek the inspiration in something that was considered to be old-fashioned and conservative. But, in spite of the mockery, I stayed close and fateful to Jovanović’s art. Paja Jovanovic was my artistic hero. Thanks to the guidance and help that I have found in his art at the beginning of my art career, I have become what I always wanted to become – a good painter, truthful to his artistic vocation and his personal vision.

|

| Paja Jovanović in his Munich studio, 1889 |

At the end, because there are not many hi-res images of Paja Jovanović’s work on the internet, and in order to show you some of his greatest paintings, I was forced to scan the images from my Paja Jovanović’s books and prints. You will certainly notice which images I am referring to.

More about life and work of Paja Jovanović you can find here or here or here

Enjoy!

|

|

Migration of the Serbs (The First Serbian Migration occurred during the Great Turkish War under Patriarch Arsenije III Čarnojević in 1690), 1896

|

|

|

Crowning of Emperor Dušan, (in 1346), 1900 (This is a hudge canvas, 390 X 589 cm. Jovanović painted a few versions of this painting)

|

|

|

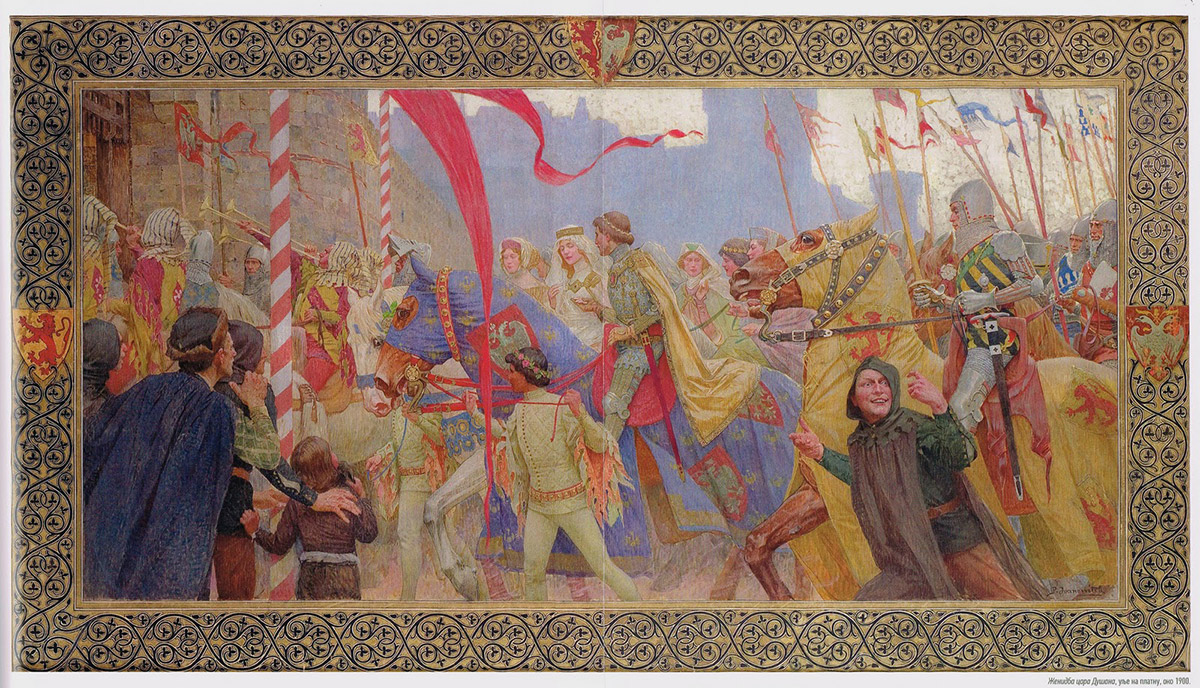

The Wedding of Emperor Dušan, around 1900

|

|

|

Uprising of Takovo ( The Second Serbian Uprising against the Ottoman Empire in Takovo, 1815), 1898

|

|

|

Return of the Squad of Montenegrins from the Battle, 1888

|

|

|

Furor Teutonicus, black and white reproduction, so called heliograph,1899 (the whereabouts of this huge canvas, about 20 square meters / 216 square feet, is unknown)

|

|

|

Rooster Fight, 1897

|

|

|

Fencing Game, 1890

|

|

|

Albanian resting, around 1890

|

|

|

Traitor, 1885

|

|

|

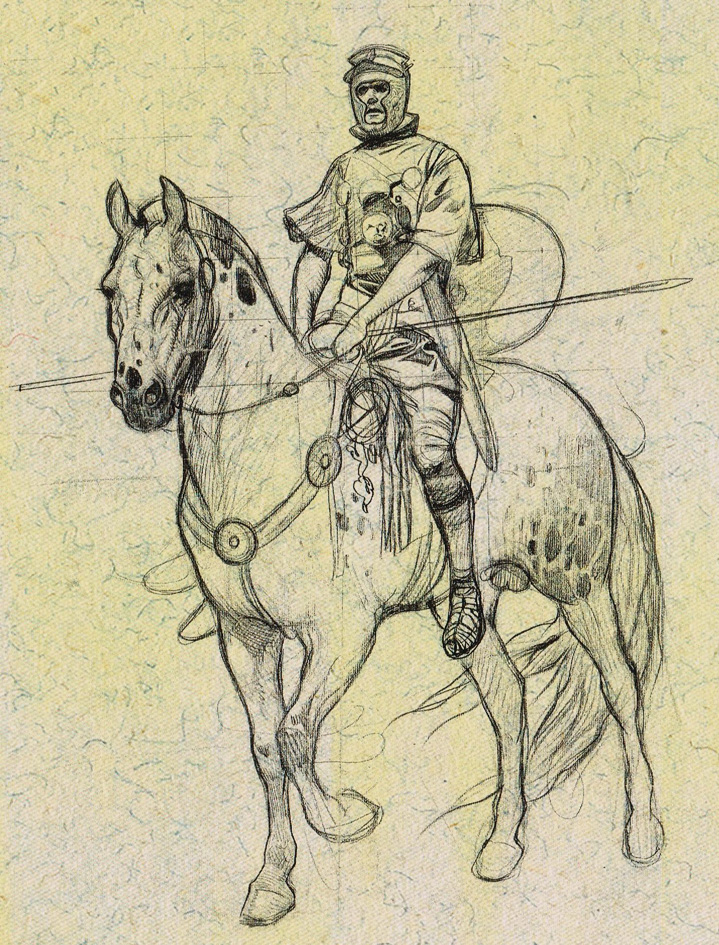

Falconer, 1890–95

|

|

|

|

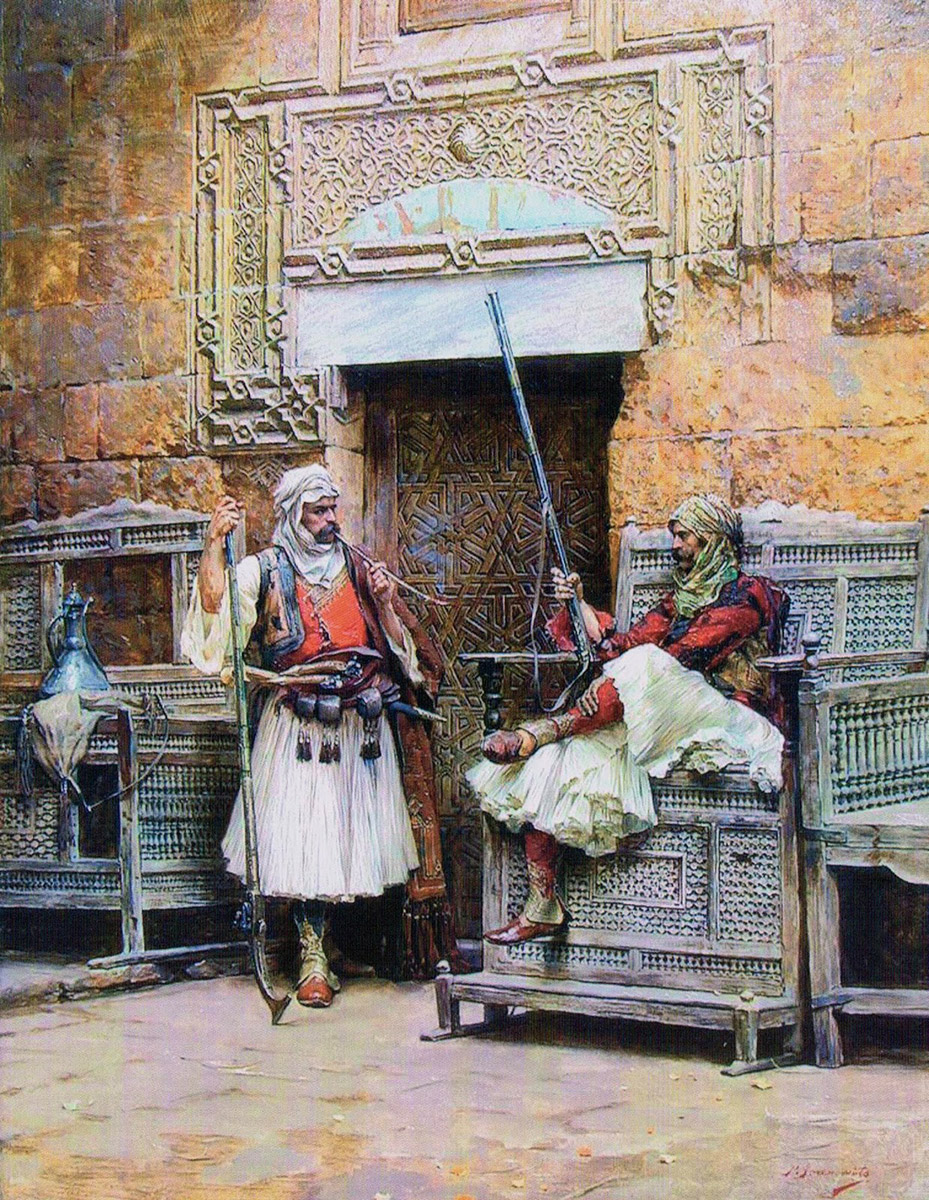

Two Guards in front of a Gate, 1888-89

|

|

|

Snake Tamer, 1887

|

|

|

Mihailo Pupin, 1903

|

|

|

King Aleksandar Karadjordjević, 1930

|

|

|

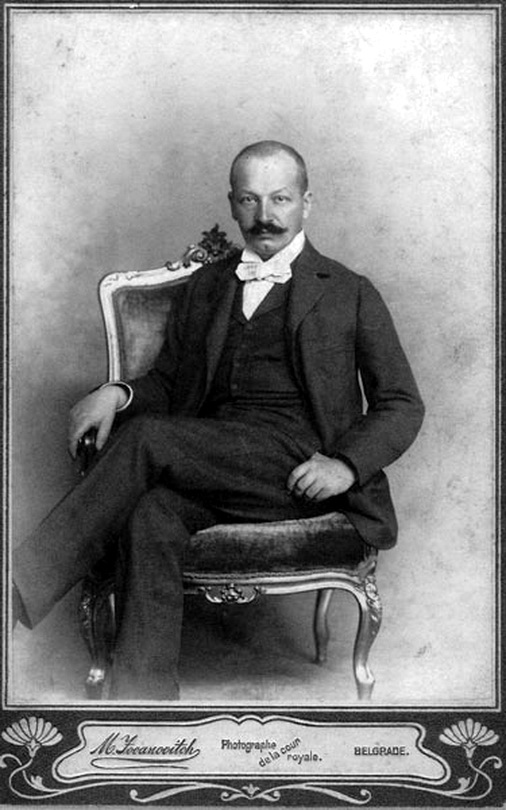

Jožef Gorup, 1903

|

|

|

Muni, the Artist’s Wife in the Salon, 1930

|

|

|

Portrait of a Lady from Vienna, 1905

|

|

|

Portrait of the painter Symington, 1902-03

|

|

|

King Ferdinand of Romania, 1925

|

|

|

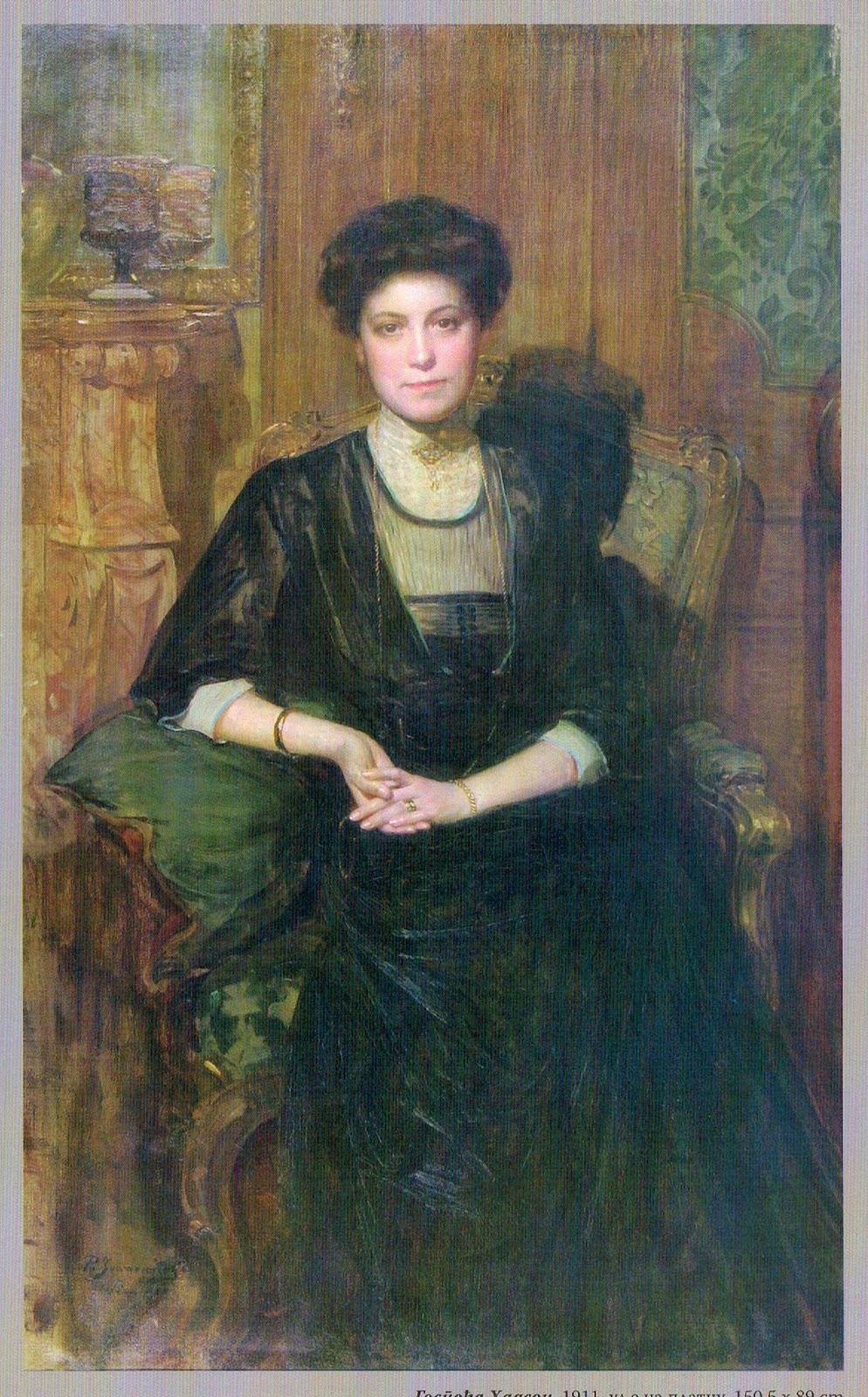

Mrs. Hudson, 1911

|

|

|

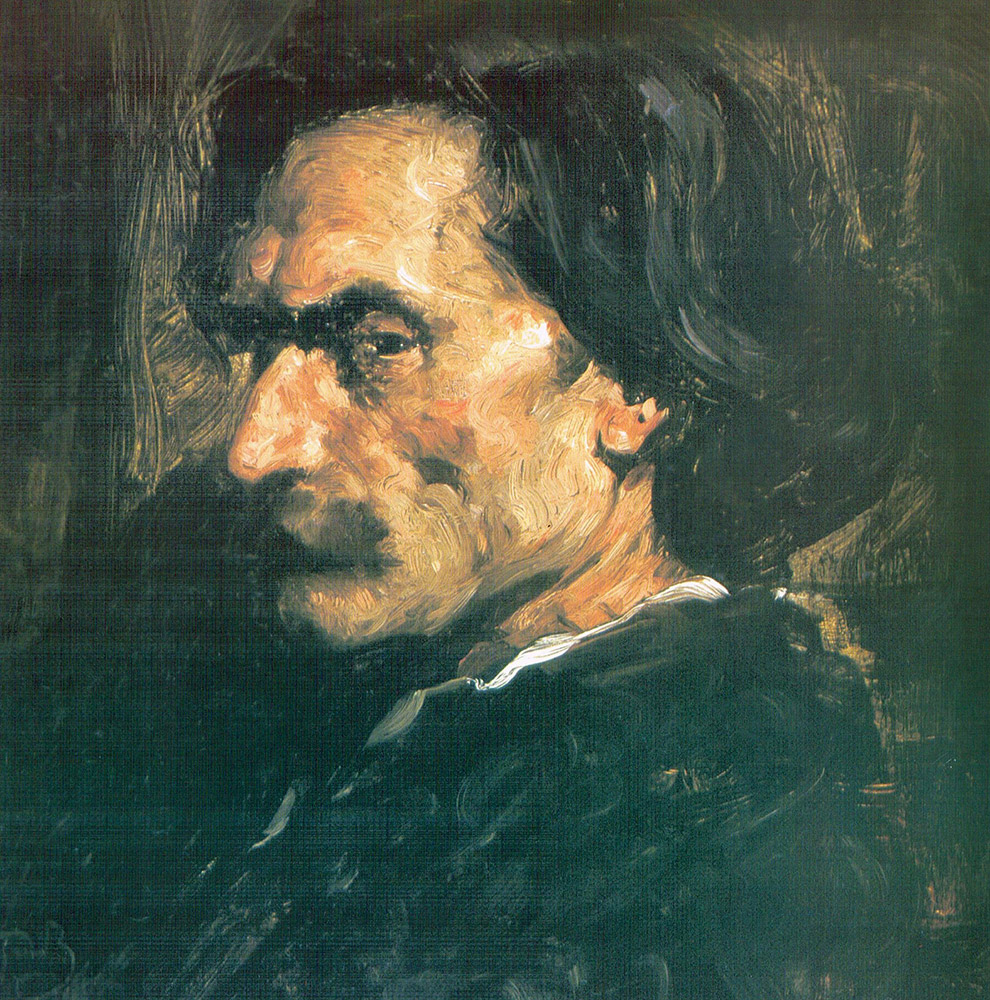

Djordje Jovanović, Sculptor, 1905

|

|

|

A Nude on Red Cloth, 1918 – 20

|

|

|

Restoring the Migration of the Serbs

|

Wow! Thanx for opening my eyes to such a fantastic painter. The romans battling the teutons is my favorite piece. I can definitely see his influence on your work.

“Migration of the Serbs”

…Good Lord, that's powerful! And judging from it's size as seen in the last image, it must be a thing to behold!

Thanks for the introduction!

….Steve

Two Guards in front of a Gate is killing me. Look at the colors on the door and wall…the details on the chairs. Damn.

Brilliant post! Fantastic art, Thank You for sharing!

Thanks for this incredible post Petar.

Great post Petar!

Thanks for this great post! What a great finding!

“Albanian resting” is straight up gorgeous.

WOW!…I am speechless!

Wonderful work!

Thank you, Petar, for exposing us to this epic and wonderfully accomplished artist. Between “Furor Teutonicus” and “Migration of the Serbs” I'm in awe — I'd love to see this stuff in person, and yet even these digital reproductions communicate such grand beauty.

The Crowning and The Wedding of the Emperor remind me greatly of the opening act of Disney's Sleeping Beauty – I think they might have been inspired by these works! Thanks for the intro to this painter!

Thanks for these Petar. Beautiful, humbling and inspiring in every way. Where can I get the book?!

Thanks for this, Petar – pointing me to a previously unnoticed master of the craft! And I can see why he's been your hero, there is an uncanny familiarity in “Rooster Fight” to another great piece of art. ;D

Thanks Paul – the book(s) can be ordered through Amazon :

http://www.amazon.com/PAVLE-PAJA-JOVANOVIC-1859-1957/dp/B005PWOEOG/ref=sr_1_10?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1326309794&sr=1-10 (this is a big 336 pages book, in Serbian and English)

and here

http://www.amazon.com/Paja-Jovanovic-Nikola-Kusovac/dp/B004HBSGCW/ref=sr_1_9?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1326204477&sr=1-9 (this one is slightly smaller than the other book, but it’s a very fine one, text is in Serbian with a short summary in English)

Thanks very much, guys! I am glad you like the art of this marvelous painter.

Beautiful paintings! We don't get to see much from your part of the world in art history class (in Southern California), so this is a special treat. Thank you.

Thanks so much for opening my eyes to such a wonderful painter! Art class can only cover so much of what we need to learn about art or what masters lay hidden in the pages of history.

if you love this..then search other painter who paintet Albanians….one of the best is Jean Leo Gerome and his Picture from Cairo sience the Ottoman Invasion about the Albanian Mehmet Pasha with his albanian irregulary Soldiers. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qkntucl7kUs

Excellent Petar,could you tell me if paja was in Paris in 1886,It may seem a funny question but Ive seen this Paris street scene painting dated 1886, painter P Jovanovic,you can see why I'm curious

Mehmed Pasha (Mehmed Paša Sokolović, with his Serbian surname) was a Serb who was taken away as a child from his parents and raised in Otoman Turks enviroment as a muslim and as a “Janičar”. Janičars was kids stolen from Serb parents and raised as muslims and that was in comon during Turks occupation of Serbian land in Balkan peninsula.

Mehmed Paša Sokolovic also erected “Na Drini Ćuprija” famous bridge over Drina River in the city of Višegrad when his rule was in power.

He was not Albanian at all. Albania as state started it's existence in 1912. yr after Austrian pressure over Serbia, Greece and surrounding countries.

Many “Moder historical writters and researches” modify key persons, facts and events from Serbian history, minimizing it's importance or giving it other nationality or belonging.

Muhammad Ali was born to Albanian parents in the city of Kavala, situated in today's Greek province of Macedonia, then a part of the Ottoman Rumelia Eyalet.[1][2][3][4]

1 Warren Isham; George Duffield; Warren Parsons Isham; D Bethune Duffield; Gilbert Hathaway (1858). Travels in the two hemispheres, or, Gleanings of a European tour. Doughty, Straw, University of Michigan. pp. 70–80.

2 Samuel Shelburne Robison (1942). History of Naval Tactics from 1530 to 1930:The Evolution of Tactical Maxims. The U.S. Naval Institute. p. 546.

3 William Wing Loring (1884). (full text) “A Confederate Soldier in Egypt”. Dodd, Mead & company. p. 28. Text ” cite book ” ignored (help)

4 George Duffield, Divie Bethune Duffield, Gilbert Hathaway (1857). Magazine of Travel: A Work Devoted to Original Travels, in Various Countries, Both of the Old and the new. H. Barns, Tribune Office. p. 79.

According to the many French, English and other western journalists who interviewed him, and according to people who knew him, the only language he knew fluently was Albanian although he was also competent in Turkish.[1][2]

1 Hassan Hassan (2000). In The House of Muhammad Ali. American University in Cairo Press.

2 Arthur Goldschmidt (2001). A Concise History of the Middle East: Seventh Edition. Westview Press. p. 195.

Interesting fact about the “Migration of the Serbs”. To counter Hungarian claims to the southeastern part of the Hapsburg monarchy the Head of Serbian Orthodox Church in the empire ordered Paja Jovanovic to paint this historic picture. In 1900 Hungarians celebrated 1000 years since their arrival in the area of Panonian plains. They commissioned huge panoramic painting “The Arrival of Hungarians” (The Arrival of the Hungarians (Hungarian: A magyarok bejövetele; commonly known as Feszty Panorama or Feszty Cyclorama). Serbs in the monarchy did not have any secular authorities, only their church in which the Metropolitan was both religious and actual leader of the people. When the first version of the painting was finished, the artist had those cavalry lances that you see in the left of the current version distributed throughout of the background. This implied that the army and the retreating people (escaping Muslim Turks) were mixed as if they were just simply running away. The metropolitan insisted that this has to change, lances to the left and people to the right, implying that Serbs settled in the south of the empire, as the organized entity, invited by the emperor Leopold (true fact) to protect southern borders against Turkish raids. Thus implying that they were legally given this land by its rightful owner (the emperor), thus negating the Hungarian claim.

Nice Informative Article.

I arrived here while researching Czech painters of the XIX century. I am glad I found this fantastic article dedicated to this great artist, which I am sure is practically unknown outside Serbia. His paintings are not only beautiful but provide an insight into Serbian and Eastern European history. At a time when Western civilization is under attack and all our national traditions are being destroyed and vilified it is very important to rescue great artists like Paja Jovanovic from oblivion. Greetings from Italy!

very interesting post. Thanks for sharing

Great post! I found this really informative.