by Arnie Fenner

Above: Tim Kirk and George Barr collaborated on this lovely and whimsical drawing for Graphic Illusions.

Above: Tim Kirk and George Barr collaborated on this lovely and whimsical drawing for Graphic Illusions.

In the pre-Internet era, young artists, writers, and entrepreneurs often combined their interests to produce fanzines (or “semi-pro zines” if they paid for content), small press publications that filled a void in the marketplace and actually advanced the appreciation for the subjects (comics, SF, film, horror, etc.) highlighted in the magazines. Artists and authors were able to hone their craft or, if they were already working professionals, experiment with subjects or ideas they normally didn’t have the opportunity to explore; publishers wet behind the ears were able to learn the ins and outs of the business while refining their design and editorial skills; readers were able to get something more than what the professional houses were putting on the news stands. Win, win, win.

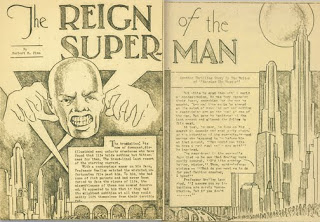

Above: The first appearance of what became Superman, written by Jerry Siegel under the pseudonym of Herbert S. Fine with art by Joe Shuster.

Fanzines were a natural extension of science fiction fandom, which in turn spawned comics fandom; it’s well known that Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster first created Superman for their fanzine Science Fiction #3 in 1933 (and eventually sold the character to National Allied Publications, much to their eventual sorrow). Ray Bradbury, Harlan Ellison, and Ray Harryhausen all produced fanzines in their youth, creating crude yet enthusiastic journals with stencils and mimeograph machines. Stephen King’s sold his first story, “I Was a Teenage Grave Robber,” to the amateur journal Comics Review, while Tim Kirk built his reputation doing cartoons for numerous fanzines, eventually capitalizing on his recognition to be the artist for the first Lord of the Rings calendar from Ballantine Books. Tim went on to design parts of Disneyland, Disney World, and Epcot and is currently working on designs for the Hong Kong Disneyland.

With the advent of off-set printing and machine saddle-stitch binding, fanzines not only became something of a higher-quality training ground for aspiring creatives, but they eventually began to compete with professional publishers for talent, advertisers, and customers. Trends, ideas, styles, and concepts were many times tried out in the more experimental amateur arena first before being adapted by the mainstream.

Now days, with the dominance of the Internet, chain bookstores, and professional publications that address many of the subjects and interests that used to be the domain of the small presses (combined with an overall decline in magazine sales), fanzines are no longer as common or influential as they once were. But there was a time when the most exciting part of the field was the small press publications. Here are a few of my favorites.

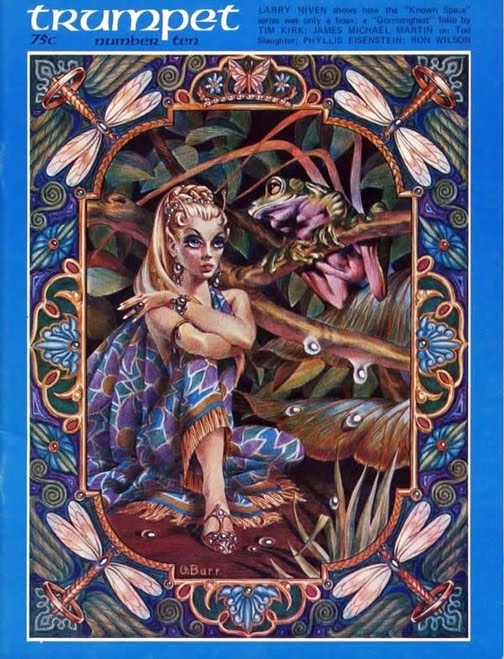

Above: Tom Reamy’s Trumpet was one of the best designed, best illustrated, and best written fanzines of its day. This exceptional over by George Barr was drawn entirely in different color ballpoint pens.

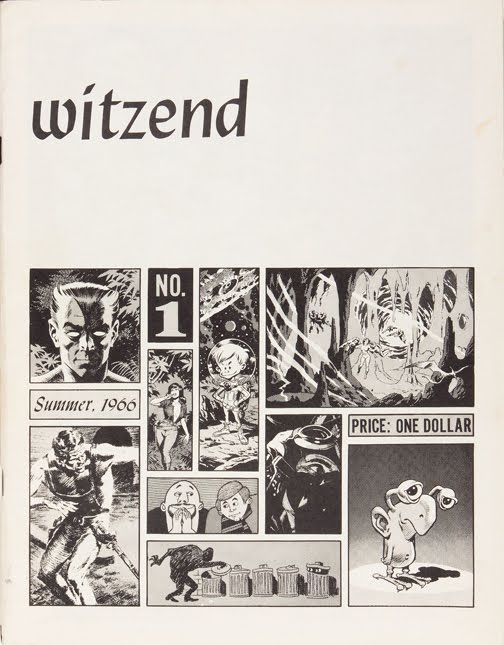

Above: Tom Reamy’s Trumpet was one of the best designed, best illustrated, and best written fanzines of its day. This exceptional over by George Barr was drawn entirely in different color ballpoint pens. Above: Wally Wood was responsible for witzend and called on many of his fellow artists—including Reed Crandall, Frank Frazetta, and Leo Dillon—to make it one of the most exciting fanzines… ever.

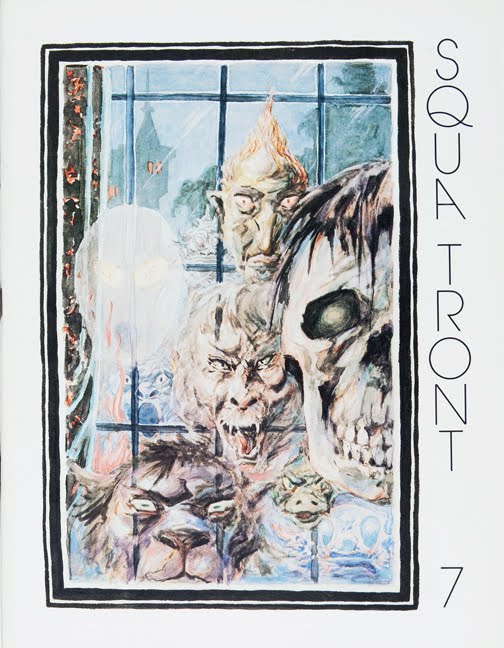

Above: Wally Wood was responsible for witzend and called on many of his fellow artists—including Reed Crandall, Frank Frazetta, and Leo Dillon—to make it one of the most exciting fanzines… ever. Above: Squa Tront, published by the late Jerry Weist, kept the interest in EC Comics and its creators alive for a new generation. The cover is by Roy Krenkel.

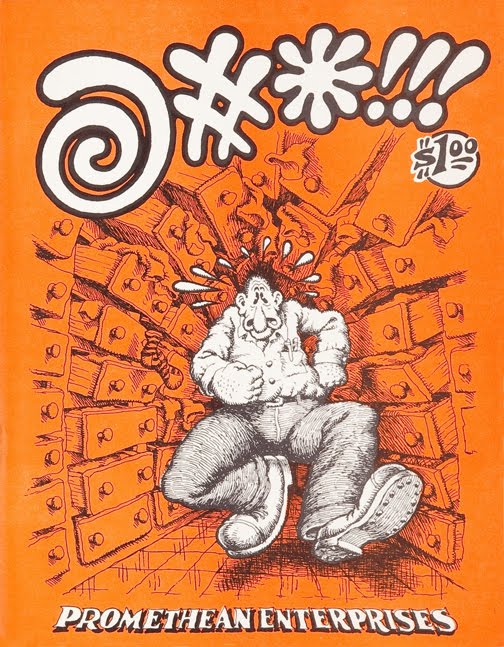

Above: Squa Tront, published by the late Jerry Weist, kept the interest in EC Comics and its creators alive for a new generation. The cover is by Roy Krenkel. Above: Bookseller Bud Plant was one of the publishers of Promethean Enterprises. The fanzine helped bridge the gap between Underground and Mainstream comics and featured early work by Robert Crumb and Robert Williams.

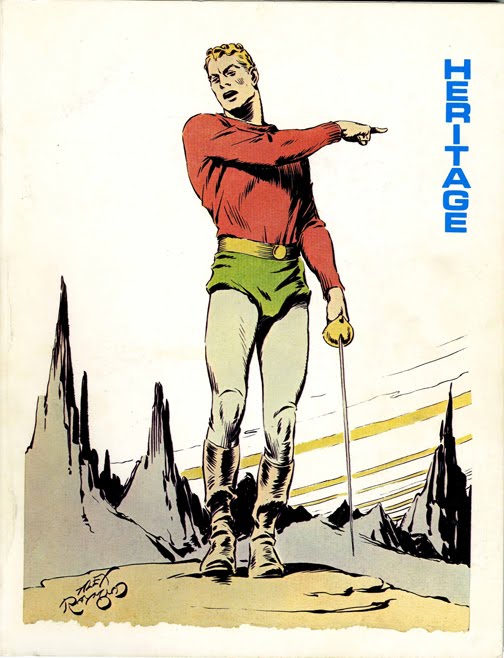

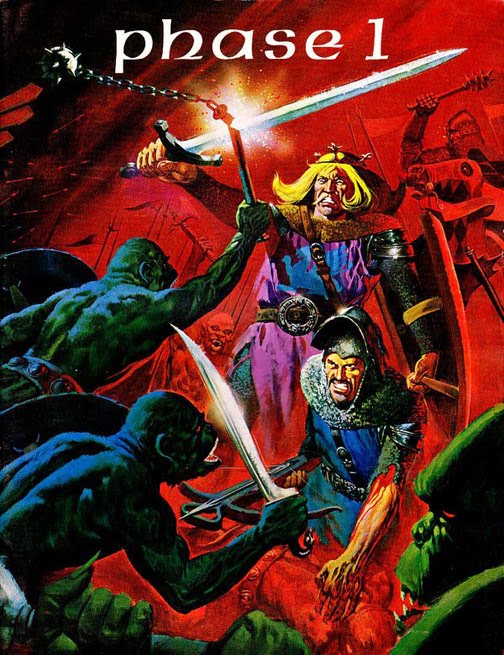

Above: Bookseller Bud Plant was one of the publishers of Promethean Enterprises. The fanzine helped bridge the gap between Underground and Mainstream comics and featured early work by Robert Crumb and Robert Williams. Above: Phase was one of the slickest fanzines ever produced and featured stories by Neal Adams and Rich Buckler that were later picked up and reprinted by professional publishers. The cover painting by Ken Barr was sold by Heritage Auctions several years ago for a tidy amount.

Above: Phase was one of the slickest fanzines ever produced and featured stories by Neal Adams and Rich Buckler that were later picked up and reprinted by professional publishers. The cover painting by Ken Barr was sold by Heritage Auctions several years ago for a tidy amount. Above: Only one issue of Frazetta appeared (though it went into a second printing with a different cover): it was an early precursor to the Frank Frazetta phenomenon that was to come. A “sort-of-but-not-really” second issue appeared as part of the Burroughs Bulletin series, but it was something of a cheat for fans that had paid for 3-issue subscriptions to Frazetta to the publisher, Vern Coriell.

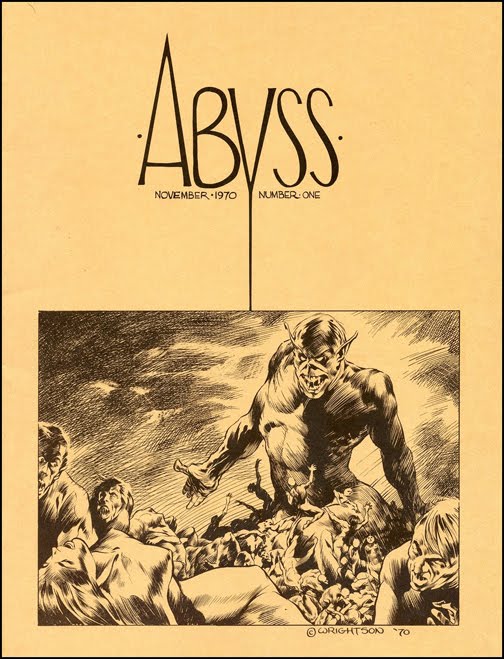

Above: Only one issue of Frazetta appeared (though it went into a second printing with a different cover): it was an early precursor to the Frank Frazetta phenomenon that was to come. A “sort-of-but-not-really” second issue appeared as part of the Burroughs Bulletin series, but it was something of a cheat for fans that had paid for 3-issue subscriptions to Frazetta to the publisher, Vern Coriell. Above: Bernie Wrightson (who drew this cover), Jeffrey Jones, Michael Kaluta, and Bruce Jones combined their talents into a single volume of Abyss. A kind of “The Studio” in training, it gave everyone a nice glimpse of things to come.

Above: Bernie Wrightson (who drew this cover), Jeffrey Jones, Michael Kaluta, and Bruce Jones combined their talents into a single volume of Abyss. A kind of “The Studio” in training, it gave everyone a nice glimpse of things to come. Above: Richard Corben (who drew this cover) and Robert Kline provided stand-out art for writer Jan Strnad’s Anomaly.

Above: Richard Corben (who drew this cover) and Robert Kline provided stand-out art for writer Jan Strnad’s Anomaly.Above: Richard Powers painted this cover for Andrew Porter’s long-running Algol. The magazine featured other excellent covers by John Schoenherr and Vincent Di Fate, who also wrote a long-running column about SF artists, something of a first for our field.

“was drawn entirely in different color ballpoint pens”

*head explodes*

Barr said that he originally did it in the hopes of interesting the pen company in licensing his art to use for advertising their products to the art community. The company turned him down, explaining that they didn't believe other artists would want to spend the time using their pens that he had. “On the one hand I think they missed out on an opportunity to sell their pens to a different market,” Barr said. “On the other, they were probably right.” Barr also drew several installments of a comic adaptation of Poul Anderson's THE BROKEN SWORD for TRUMPET. Truly gorgeous. Unfortunately, it was never completed.

Back around 1980, my high school art teacher let me borrow several of his treasured copies of Witzend (including No. 7), and Vaughn Bode subsequently shorted every circuit in my little brain. For the rest of that year, I was off and running, locked in my room india-inking on heavy construction paper and cutting Zip-A-Tone, making up my own Cobalt 60 stories (which were pretty rubbish).

Mr. Clark, if you're still out there somewhere… I am eternally grateful!

We had a young student artist at the last Amherst College Thursday night figure drawing session using a blue ballpoint pen. When the right people get a hold of a ball point pen, man-o-man they can do some very wonderful work.

The young woman did some fantastic studies. I hope she attends the rest of the semester and continues to use her ballpoint pens.

Back to Fanzines… are there any internet based fanzines going on now?

Thanks,

Mike

Very cool post Arnie.

Yeah that's amazing!

“Marion Zimmer Bradley's Fantasy Magazine” ran from 1988-2000. It was one of the major fan or semi-pro zines to feature the work of female authors and artists.

Is it possible to find copies of these anywhere? Even digital ones? These look so great and inspirational that it's a pity to not have access to them.

Michael–

It IS possible, but requires some searching. Most of the fanzines had print-runs of 1000 to 3000 (more in some cases, fewer in others) so they're not always easy to find. Ebay is a pretty good place to start; dealers like Bud Plant, Greg Ketter, and Stuart Ng usually have some (or know where to get them). You can also usually find fanzines in the dealer rooms at the various comics and SF conventions. Good luck!

I have every one of these except @#*!!! How scary is that? These things were always uneven content wise, but always had at least several little gems in them. I picked mine up in various comic shops over the years.