by Arnie Fenner

And by C&C I mean Compensation and Credit. That’s pretty much a no-brainer for any artist, and yet there are plenty of folks out there who will happily deny you both if allowed.

Don’t let them.

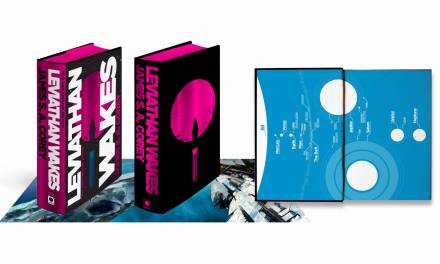

The copyright laws these days are pretty clear-cut: you own what you create until you assign those rights to another…or give them away. Give away? Who would do such a thing? Well, more than you might think.

Now copyright is a gigantic can of worms I’m not prepared to open very wide with this post: it’s a complicated issue that few agree absolutely about, which is made only more abstruse and puzzling by the internet and social media. Anyone who claims to be a copyright “expert” (including plenty of lawyers) is probably full of baloney: interpretations of the laws are constantly being challenged, revisited, and revised. Toss in mentions of Work for Hire and the Fair Use Doctrine (which grants others the right to use your art without asking in certain circumstances, such as in news stories or as part of an educational or historical publication/presentation) and the “rights” conversation only gets more confusing. So I’m going to keep it simple and leave off the varnish:

Don’t let people use your art without permission. Don’t let them print it, copy it, share it on the web, or otherwise publish or disseminate it in any way without your say so.

With the current laws the onus is placed on you to protect your rights; there isn’t a Copyright Cop asking anyone if they had gotten permission before using your painting for whatever they want to use it for. Corporations have lawyers patrolling their territory, but you’re pretty much on your lonesome to ward off pirates. If you find someone that has used your work without authorization, you can’t shrug it off: unless you challenge infringers whenever they’re encountered an argument can be made down the line that you’ve abandoned your rights and made them freely available to whomever wants them. (A “laches defense” that, if successfully argued—as it often is—could…no, no, no, no! I said I wasn’t going to get into all of the vagaries of copyright this time and I’m gonna stick to my guns.) So…you have to be vigilant and you have to be selective with how and where you make your art available.

It goes without saying—but I’ll say it anyway—that you should confront anyone who uses your art without asking you first. Begin nicely, but if you get attitude as a response, give it back in spades. It’s a hassle, it’s stressful, it’s infuriating, and potentially expensive to make the other guy accountable but…infringement is infringement. I don’t care if they’re friends, relatives, amateurs, or pros; it doesn’t matter if they “assumed” or “thought you’d be pleased” or “didn’t make any money” or any other half-assed excuse they might make. You don’t take their car or enter their home without their permission and they should not be allowed to use your art without yours,

And when you do grant permission for someone to use your work, get something in return.

(A social media aside: Under the terms of Facebook and similar sites, you have agreed to “share” with members anything you load and they in turn have the right to share your stuff with others. That’s not waiving your copyright outside of FB’s confines, but it can make your work readily accessible to the unscrupulous and be difficult to track or control use.)

Where was I? Oh, yeah: getting something in return.

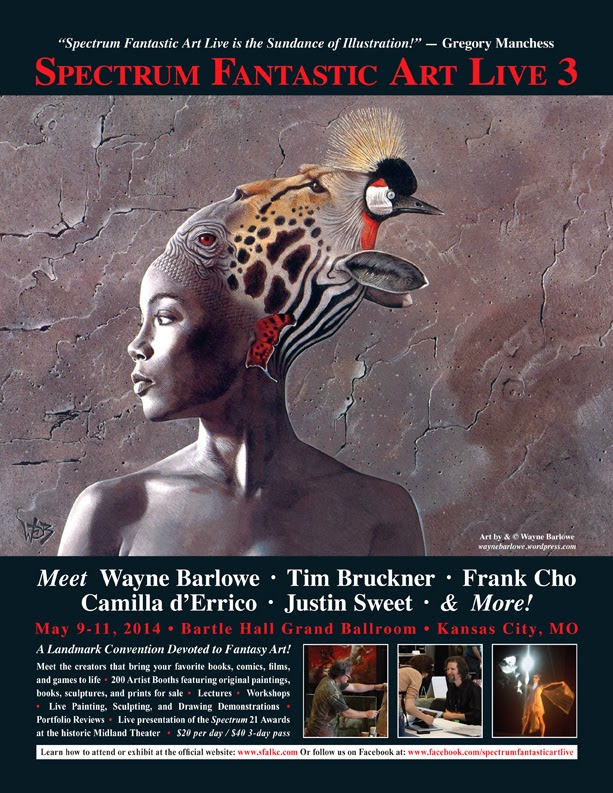

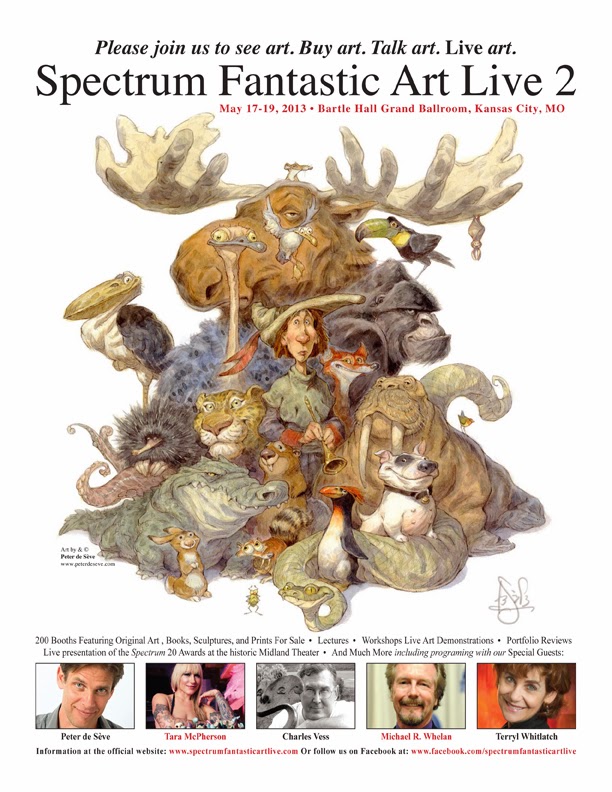

Regardless of appearances or perceptions, not everything makes money, not every project is for profit (or for very much profit) and if you want to allow someone to print your art after they’ve asked nicely—in a magazine or a book or on a poster or as part of a convention souvenir or in an exhibit catalog, whatever—that’s your right. But part of the deal has to be that your art is properly credited with your copyright and that you get, at the bare minimum, a copy of anything published that features your work. Don’t listen to the crybabies who whine about the cost of producing this convention book or mailing that catalog. Your generosity should not be rewarded with discourtesy: their bank account is not your concern. And for God’s sake you most certainly should not be expected to purchase anything that you’ve granted permission to publish your work. Don’t be shy about demanding a copy and don’t take “no” for an answer.

We teach people the way to treat us: unless you place a value on the use of your work, why should they?

Likewise with receiving credit for your art.

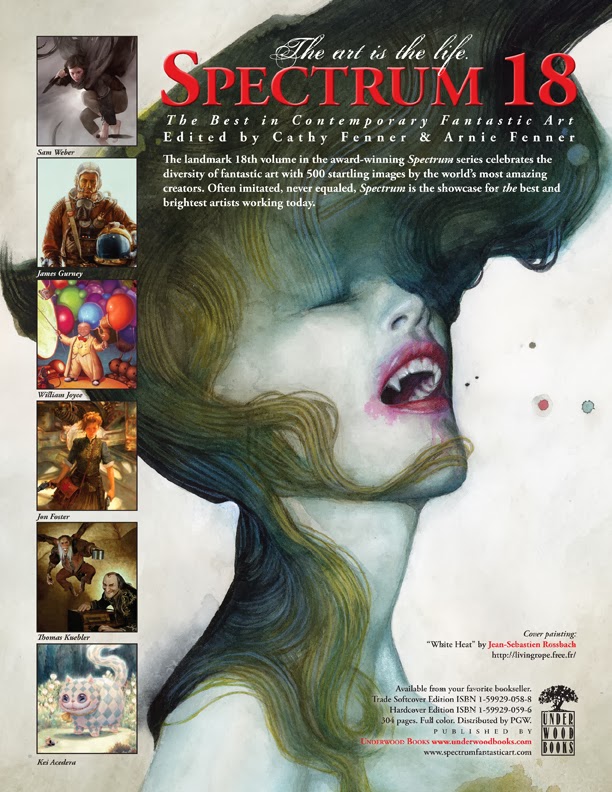

Having your name appear with your work can grow the audience’s appreciation for what you do and get the attention of potential clients and art directors. You should not rely on a signature in your work to be sufficient (they can often get cropped or covered by type), but should insist on a credit/copyright notice whenever your art is published or put online. It’s a friggin’ line of type: it doesn’t cost anything, but you’d be surprised at how stingy some can be in giving it. Just because you’re doing Work For Hire (which is common in the comics, game, and entertainment fields) and are reassigning your copyright to whomever as part of the job, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t or can’t receive credit for your work.

It doesn’t have to be hard: just include a line in your invoice or contract or any other communication stipulating that a credit for you accompany your work every time it’s used. If it is your client’s contract you’re signing and no mention of credit is made, write the requirement on every copy, date, and initial it. Most clients honestly don’t think about it or really care and are happy to accommodate. If on occasion you get push-back, it’s an opportunity to have a discussion.

Admittedly there are circumstances when you might not get it. Advertising is notoriously reluctant to credit artists, partly because of the old saw that they don’t want to distract from the message of the ad. (All a bunch of hooey, especially when you consider the legalese and fine print most ads run as a matter of course.) Warner Bros. or Sony or any other major corporation will probably smile and refuse, but it never hurts to try: persistence can sometimes pay off.

But when it comes to freebies, in print or online, never let anyone use your work without crediting you.

A big part of being a professional artist is managing your assets: recognition for your work and acknowledgment of your copyright (when you retain it) has value. Receiving copies of where your art appears is a document of your career (and history of use of various works, which can be important when licensing of secondary rights comes into play) that can have value to you in the years ahead.

Don’t willingly let anyone rook you out of either.

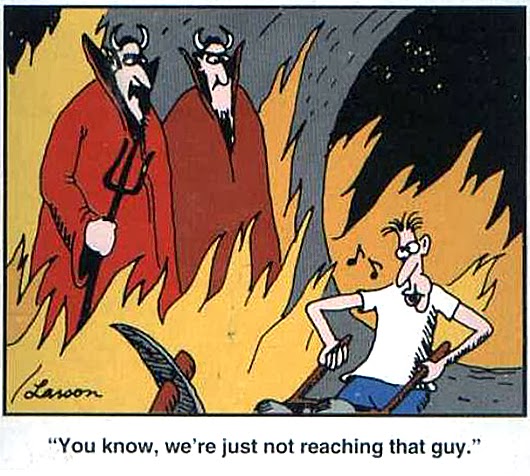

It seems so obvious, doesn't it? I swear, the arts must be the only profession where the laborer thanks the person taking advantage of them for the great 'opportunity'.

i've just read an article about creative jobs and creative processes. It said that those kind of jobs will be some of the few jobs that will survive in the future, because they can't be replicated by computers and artificial intelligence. It talked about the relevance to pay them and recognize their merit due to educate the people to see them as the relevant jobs that they are.

This post has natural connection to that i think!

One of the biggest challenges the creative community faces is the false perception (on the part of businesses and the public alike) that what we do is “easy.” The process, regardless of the tool, tends to be taken for granted and, as a result, often unappreciated. But…an artist—be they illustrator, designer, art director, sculptor, or photographer—is involved with every single aspect of our lives. From the cars we drive to the packages are food comes in to the things we read to the clothes we wear to our homes and what's in them ALL are a result of artists and the creative process. So, yes, Bea, I agree with you! 🙂