Last week, while recording an interview for an upcoming episode of Creative Trek, I was asked to share a piece of advice which has stayed with me over the years. A few jumped to my mind at that moment and then later that day I kept thinking of others, so I thoughts I’d jot a few down here on Muddy Colors.

1: Be prepared to pay your dues

I grew up in a family of artists, so it is inevitable that much of the good advice I’ve received over the years would come from my parents. This was one that I heard again and again before I even began learning to paint. Basically, be grateful for every job you can get because it takes a long time to climb the ladder. Not every job is going to be fun and/or easy, so be ready to tackle the low rent and uninspired jobs with a professional attitude. Looking back, I find this to be very much a tightrope. On the one hand, you don’t want to be taken advantage of and there are plenty of people out there looking to exploit you as far as you will let them. Opposite that, you need to be humble and know that, at least when starting out, you should be following up as many opportunities as possible. Finding the balance is hard and I think most of us only get it after several stumbles, but a humble attitude will help a great deal. I’ve seen several people with tremendous potential wash out because of their egos and an attitude that the world owed them some kind of special treatment. This is not really a business for prima donnas.

2: Don’t teach yourself the mistakes of others

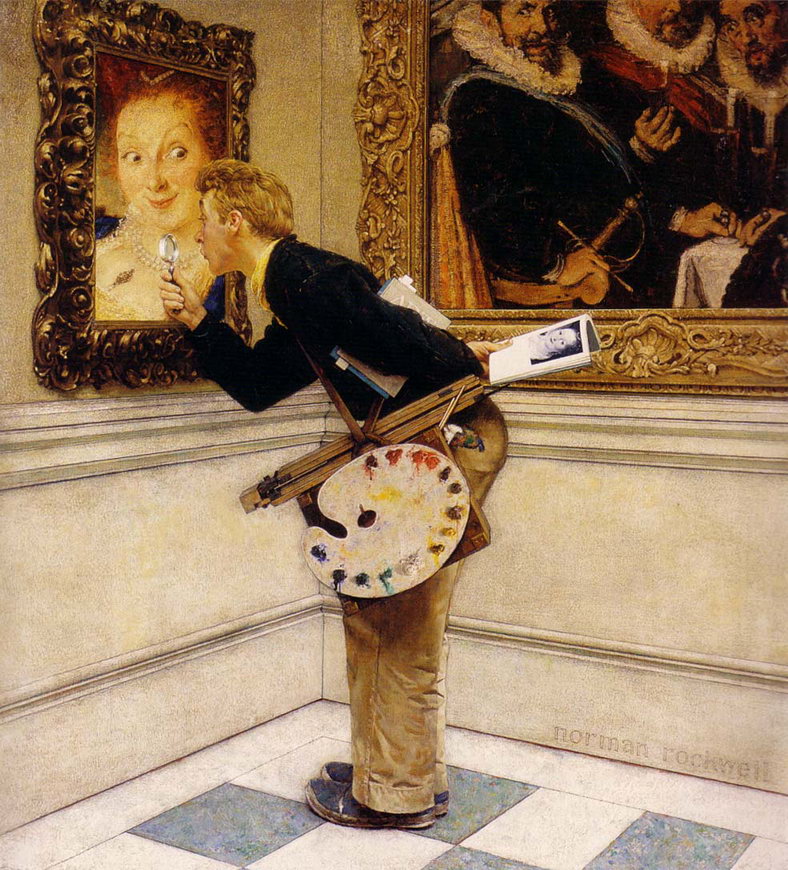

Early on, I had some ideas about working as a comic artist and was fortunate to have a portfolio review by Joe Quesada. After looking at my (in hindsight) very crude pages, he told me that he felt I was looking too much at other comic artists and not enough at real life. He told me that, while you can learn a great deal by copying the work of those who inspire you, the vast majority of your study should be direct observation. When you copy another artist, you are copying their mistakes and teaching yourself their bad habits. Working from life, on the other hand, lets you train without that baggage clouding up the picture. You are much more likely to develop your work into something unique if you learn from the world unfiltered.

3: Lead with the work

About the time that I graduated from PAFA, I was exploring fine art and had a meeting with Neil Zukerman who runs the CFM Gallery in Manhattan. He was kind enough to talk with me not only about my work but about making contact with galleries cold. Basically, when someone walks into a gallery off the street and requests a review of their work, the automatic assumption is that it will be either a poor fit for that gallery or just simply horrible. To save everyone a lot of time (and to avoid the automatic brush-off), he told me to introduce myself while simultaneously handing the curator a sample (print, postcard, etc.) of my very best work. Maybe they will be interested and maybe not, but it will get things right to the point and hopefully let you lead with a good first impression.

4: Don’t worry about being fast, just worry about being good

In my first (of several) portfolio reviews with Magic the Gathering art director Jeremy Jarvis, he wondered if I might be rushing my work. Many aspects were sloppy and would have been much stronger if I’d simply slowed down and taken my time. Speed comes from the confidence of experience and, if I wanted to be fast, I first had to learn how to slow down and get good. Nobody is impressed that you turned out a bad piece quickly, but they are impressed when you turn out something really good.

5: Don’t forget to push the design

A year later, I sat down with Jeremy Jarvis again at that same convention for another review. My new portfolio had all new work which I had taken my time with and paid close attention to strong technique. What I’d failed to pay attention to was my character, costume, and environmental design. Jeremy pointed out in piece after piece where I could have pushed things to be more interesting, more lived-in, more unexpected, and just MORE.

6: Don’t be scared to be different

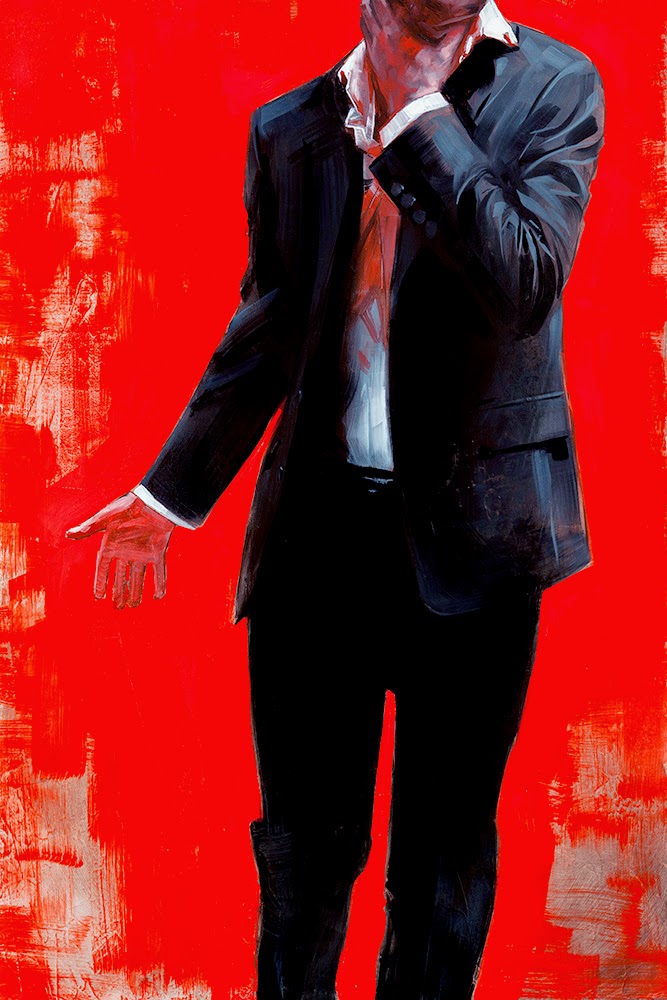

As I was starting to get work more steadily, I began feeling frustrated in my process and technique. I had always felt that, to be a fantasy artist, I should be working in a tightly rendered highly detailed and polished style. After all, that is what fantasy art usually looks like, right? My frustration was that I was growing more and more interested by painterly work along the lines of NC Wyeth and other early 20th century illustrators and this was at odds with the mainstream looks. I was lamenting this to Greg Manchess, one of the few current fantasy artists I knew who did work outside of that tight render box. After going on and on about how I wished I could work looser but was worried about this and that and the other thing, he just said something along the lines of “well, yeah, I don’t know, why don’t you just try it?” I was struck by how simple that made it seem and how ridiculous it was to have not realized this myself. It was a few years before I really changed my process, but in that time I was working on personal pieces and experiments which ultimately proved to me that I needed to shift direction. The first and most important step was to stop worrying and just do something.

7: Make your work with purpose

This last one was not advice given specifically to me, but something which I’ve heard Rebecca Guay say to students many many times. Whatever you make, you need to make it your own in some way. Find something to love in every piece, find something personal to contribute to every assignment, and always know what you want for the viewer to feel when they look at your work. If you don’t make your work with purpose, it will have no impact.

David, you and Greg always write my favorite posts on Muddy Colors, and this is no exception. Sage advice, and gorgeous piece at the top too!

Many thanks for this: I'm trying to get work as an artist/woodworker/storyteller rather than a visual artist but what you say has a lot of relevance to what I'm trying to do, and I can see how to apply some of your suggestions to my own work. The comment about speed and experience is also very encouraging as I'm on the edges of an industry where only speed is valued and it is easy to get sucked in…

This is very well done, thank you for posting this! By the way, the piece at the top reminds me of another piece of advice that I have heard a time or two….don't cut your own throat, let the work speak for itself! (Don't apologize for your works short-comings)

This post was so, SO freaking spot on in this very moment of my creative life, that it brought me to tears. Man, you made a significant epiphany snap inside my twisted mind. I just can't thank you enough for sharing this ridiculously insightfull amount of brilliant advices.

Being an illustrator still struggling to settle myself among clients and fighting with myself defining what approach I should develop to “please” the clients and audience (even knowing that this isn't exactly how I'll make it work, but still), I couldn't relate more to your words. My absolutelly deep love and interest for a painterly approach is talking higher and higher, and even if it won't fit the market as I wish it could, I simply can't help it. Now that I'm reapproaching my deepest/strongest passion for oil painting to pursue more of that painterly feel, I feel EVEN more encouraged to deliver myself completelly to it, even if painting will not give me any immediate results, professionally – on the opposite, I think I'll suffer even more, but I'm sure I have no other option, than to continue the journey until I find a way, to make the painterly look (both digital and traditional, but especially the oils for a gallery attempt someday) find a place in the illustration/fine art markets.

Sorry for talking so much about myself, I just wish you could see inside my head and feel the wonder you made me feel. All the very best!

And… “This is not really a business for prima donnas. ” This might be the very best piece of advice of all times, wish everyone could read this. 😉

Speaking to the issue of worrying over being able, or creatively inclined, to fit into the blanket fantasy painting style, I appreciate your sharing your struggle. And the subsequent advice you received is inspiringly simple. I think it is tragically comic how as creative individuals we can hum and haw over the very risks that make our work our own, and give us an edge, professionally. Yet, those green or young in the field are just…scared of taking a step that takes them father from making a living at their passion. Myself included. These wise reminders are a beacon on the rough days. Cheers, David!

I'd like to pretend that was my intention, but I suppose it was just serendipity! A great point to remember though, I cringe when I see people doing that!

So glad to hear it! I've come to realize that we don't truly know the market and trying to work towards it based on what it seems to want is some sort of self fulfilling prophesy. Though it makes me less desirable to certain clients, my shift towards more personal (which in my case is also more painterly) work has definitely pushed my career forward rather than backwards. We can't and shouldn't try to be useful to every client, it is much better to be really exciting to the ones who get what we want to do. I had no idea some of the new doors it would open to take a more personal approach because I didn't know what doors to look for.

Really glad to hear it it clicked for you like that, so exciting!

Find something to love in every piece, find something personal to contribute to every assignment, and always know what you want for the viewer to feel when they look at your work. If you don’t make your work with purpose, it will have no impact. Telepathy show

I love this, Dave. Spot on.

Excellent advice 🙂 Thank you for the post David.

Your reply was EVEN more exciting!! This is EXACTLY the feeling ruling my heart right now. I'm SO glad to know that pursuing the personal journey is not that crazy, after all. I mean, it IS crazy, and THAT is why it's so thrilling! 😉 Thanks for your time, sir – you're inspiring me (and hppefully a lot of other folks) in a way that words couldn't precisely desccribe. Will get in touch soon!

Great post. I especially like, 'Don't forget to push the design.' I think I'll take that particularly to heart as I work this week.

Thanks for this. I have ALWAYS wanted to do fantasy work, but have always been terrified that my ideas aren't original enough, and/or that my style doesn't fit the genre.I've always had a deep, passionate love for the classical romantic painters, but have never known how to make that fit anywhere in the current art world. However, after seeing Annie Steggs work, and reading this article, I'm just going to give it a shot. You never know until you try right? Besides, who wants to be just like everyone else?

Bravo! This is wonderful! Thank you, Dave!

Thank you for taking the time to write this for us David. Like Rafael, the content and the timing of its delivery is perfect. Important questions have been answered!

Some great stuff here David, thank you:)

Don’t worry about being fast, just worry about being good.

I’ve students self-conscious about working slower than other students. I’ll be sure to pass this information along.