I have another treat from the my visit to the Tate Gallery. Like Millais’ Ophelia, this painting deserves it’s own post.

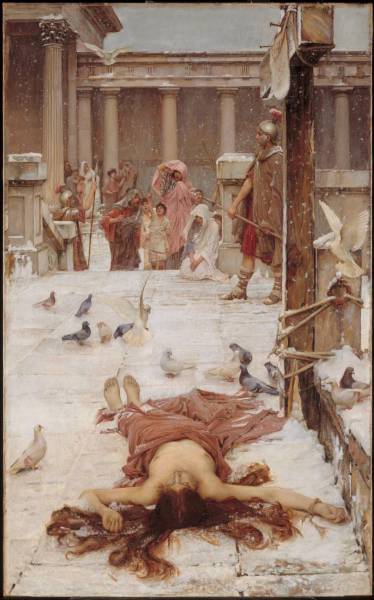

The foreshortening in this painting has always amazed me. Waterhouse possessed remarkable drawing skills. I love how he simplifies but also adds plenty of detail to reward close inspection. This is an emotionally moving painting for me. The contrast of the nude corpse, still bearing the color of life, against the snow and framed by the onlookers, is powerful and tragic. Even without knowing the story behind the painting, it bears a solemnity and you engage with those mourning in the background. The cold environment is matched by the apparently indifferent guard. He stands intimidating with his spear pointed to the onlookers, but also relaxed and unmoved by St. Eulalia’s death or the sorrow of her followers.

There is also a beautiful geometry to this composition. The columns create a sequence of rectangles that form dramatic verticals. They are fronted by the strong shape of the cross projecting upwards out of the image. The line of the roof ends the verticals as does the far end of the plane that the figure of St. Eulalia lies upon. The space in the painting is divided up into many smaller shapes making an interesting patchwork of geometry to either frame figures or serve as a backdrop.

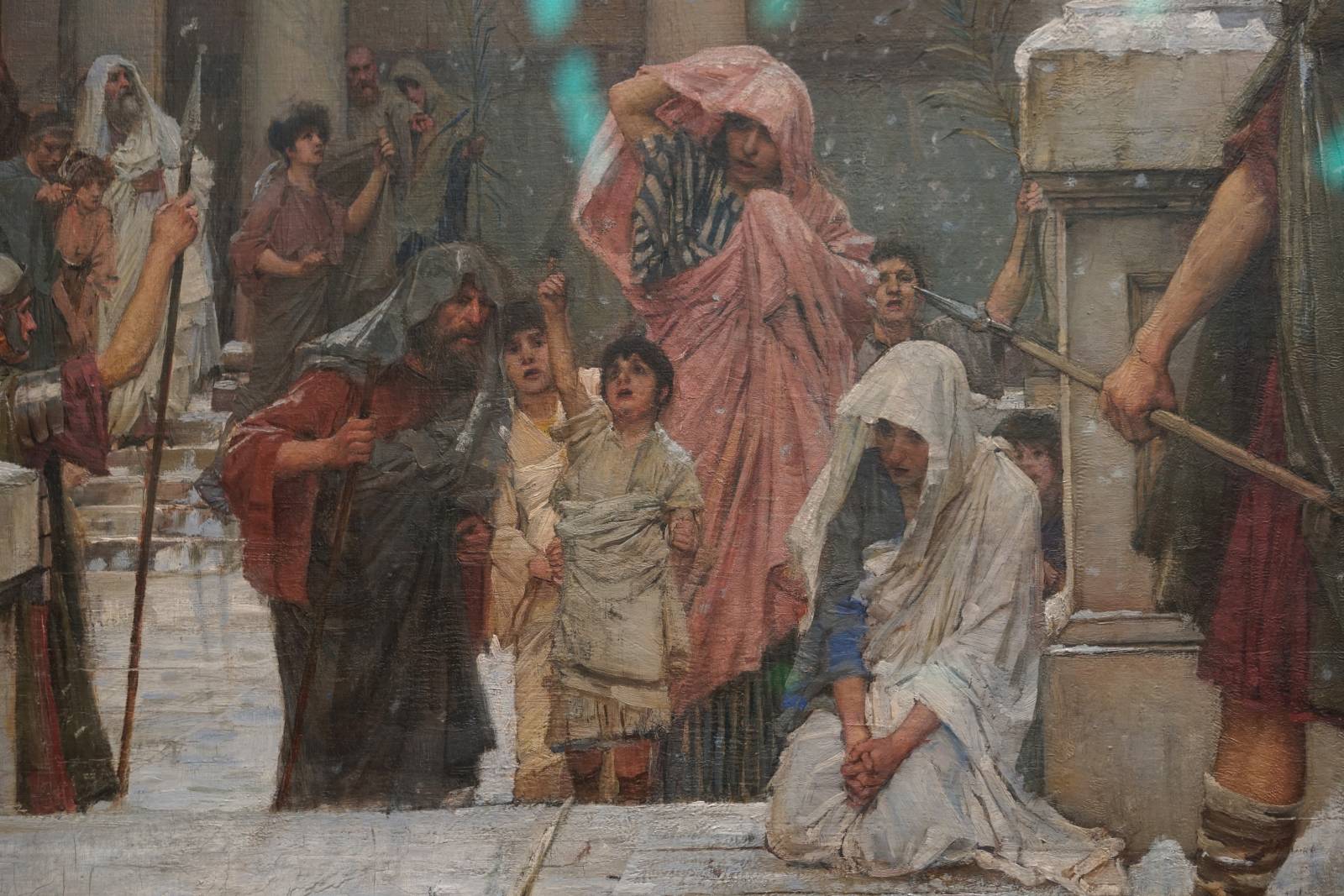

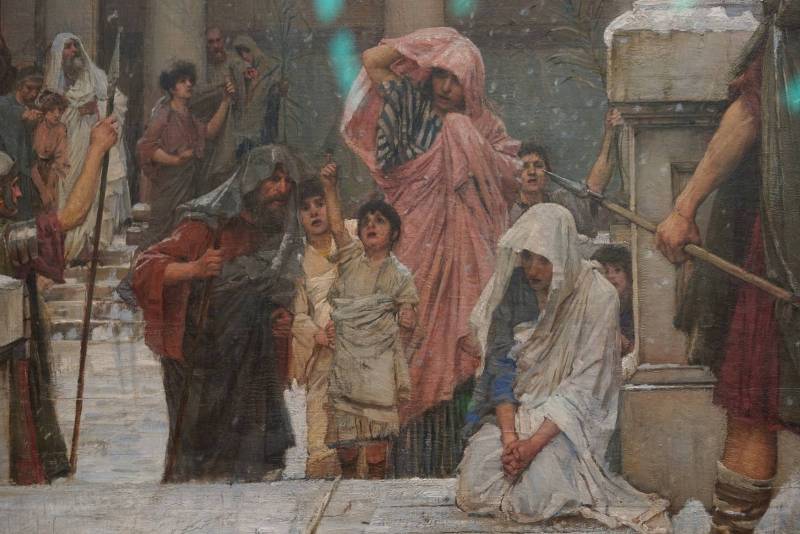

All of these elements are apparent in the reproductions I have seen. What wasn’t clear was how loosely painted it is and how textural it is. Having seen a few Waterhouse paintings, you’d expect this, but until I saw it in person I didn’t know. I managed to grab a few details shots while there.

I still can’t get over how loose the painting is up close. It seems so detailed in the reproductions. The painting isn’t in great shape. Unfortunately that is also fairly typical of Waterhouse. He has complaints in his lifetime of cracking and delaminating.

Look at how quickly and loosely the snow is painted. Waterhouse added just enough to make it appear as snow.

Forgive the green light reflections in some of the images. Almost all the paintings in the museums in London are behind glass. It is my understanding (I asked) that this comes from the time when coal was burned and paintings needed that extra protection.

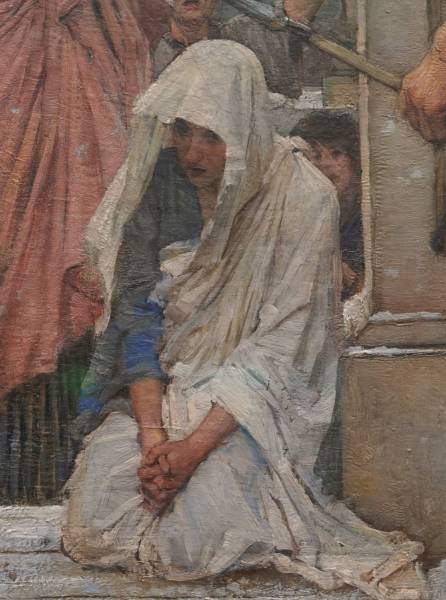

I love this beautiful, sorrowful mourning figure.

Here is the description from the Tate page for the image:

Waterhouse exhibited this picture at the Royal Academy in 1885 with the following note: ‘Prudentius says that the body of St. Eulalia was shrouded “by the miraculous fall of snow when lying in the forum after her martyrdom.”‘

St Eulalia was martyred in 304AD for refusing to make sacrifices to the Roman gods. The method of her death was particularly gruesome: two executioners tore her body with iron hooks, then lighted torches were applied to her breasts and sides until finally, as the fire caught her hair, she was suffocated. Given the horrific circumstances of her death, and Eulalia’s tender age (she is said to have been twelve years old), Waterhouse demonstrates little concern for realism. The setting for the picture is supposed to be Merida in Spain, which was then under the rule of the Roman Emperor Diocletian, but has been transferred to the Forum in Rome. Eulalia’s body appears totally unharmed, her exposed breasts and flowing hair giving her a seductive rather than pathetic appearance. Although there is snow falling and lying on the ground, her body is uncovered. As an explanation for these alterations to the legend, the artist includes a wooden cross on the right of the composition, implying that the martyrdom was by crucifixion.

The composition is extremely daring: Eulalia’s dramatically foreshortened body leads the eye towards a void at the centre of the picture. A group of mourners form a pyramid towards the top of the composition, but the viewer’s eye is drawn back down towards the martyred figure by the right-hand soldier’s spear, via a zig-zag of ropes, to the young woman’s outflung arms. According to the account given by the Spanish Christian poet Prudentius (348-405), at the moment of her death, a white dove emerged from Eulalia’s mouth and flew towards heaven. Waterhouse refers to this event by including sixteen doves in his painting. The youngest mourner points upwards at a single hovering dove towards the top of the picture, a symbol of Eulalia’s departing soul.

The picture was well received by the critics and secured Waterhouse’s election as an Associate of the Royal Academy. One reviewer approved in particular of the image’s simplicity and idealism and its avoidance of the grotesque. He wrote, ‘the conception is full of power and originality. Its whole force is centred in the pathetic dignity of the outstretched figure, so beautiful in its helplessness and pure serenity, so affecting in its forlorn and wintry shroud, so noble in the grace and strength of its presentment’ (quoted in Hobson, pp.34-7).

Thanks for giving the post a read. I hope you enjoy the detailed shots. Be sure to save them or open them in a new tab so you can see all the detail!

Howard

Damn Howard! I’ve seen this too and only just now (or maybe my memory is going!) spotted her legs do NOT go straight out but lie to her left thus giving the impression of ‘wrongness’. Thanks for the highlighting of this great painting

Thanks Howard for another gem! The dove has such a great expression and the mourner is just fantastic.

Catherine Nixey’s book “The Darkening Age” presents a different view of Eulalia, based on Roman sources. According to the presiding magistrate Probus, a fervent group of these early Christians were indulging in a suicide cult, hoping for a ticket to the afterlife. Romans tried to talk Eulalia out of killing herself: “Don’t you see the beauty of this pleasant weather?” Probus pleaded with Eulalia. “There will be no pleasure to come your way if you kill your own self.” According to Nixey, the Christian version of events, which has shaped the official history, portrayed her instead as an innocent martyr.

Thank you for the additional information James. These old tales are a well spring of information.

Thank you, Howard, for another gorgeous post. Your contribution is praiseworthy and extremely valuable.

Thank you for your this examination Howard. It’s always a good time exploring the the masters with you.