Over the course of my education I repeatedly ran into two disparate points of view regarding the creation of an image.

Philosophy 1:

While drawing thumbnails, one’s first instinct is usually the strongest, and while one may continue to explore other possibilities for solving the problem, one will invariably tend to circle back to that first instinct.

The notion of trusting your instincts is something that I think appeals to a lot of folks. It certainly appeals to me. Considering how much I doubt my own work and process, the idea that at least the foundations of the image I’m creating are on target is a comforting notion. At least potentially.

Philosophy 2:

While drawing thumbnails, one should take that first instinct and immediately discard it.

Why toss away your first instinct? Simple. The first instinct has the greatest likelihood of being a cliche, and as nice as low-hanging fruit may be, they’re not always the sweetest. With some sweat equity and pencil mileage put in, an image can be something greater. Or so I’ve been told.

During my schooling, I did not know how to reconcile the two views at the time, honestly. I was busy flying by the seat of my pants, trying to hand in assignments on time and pass all my courses while holding down a job. In practice, what I did was create a bunch of thumbnail sketches for each project and go with what I liked best. If challenged by a professor who felt that the first instinct was the worst instinct, I could point to some alternate take as that which I’d abandoned.

But in reality, none of my professors brought it up. Sure, I had professors from both schools of thought look at all my thumbs and challenge my thinking and process, but I was never held strictly to either philosophy.

Why was that?

Simple. I’m pretty sure that regardless of what any of my professors…professed, they knew that neither philosophy works 100% of the time.

In reality, one’s first instinct isn’t always the most cliched, so why dismiss it straight away? While one may have arrived upon a preliminary image via the most easily traveled highways of one’s brain, that doesn’t necessarily make it a cliche. More likely than not, what it means is that it’s as straightforward a take on something as possible. It’s a version that likely communicates the idea fairly directly and succinctly. But that doesn’t mean that it’s the right solution for every challenge.

And maybe that first idea is a bit obvious, a bit tired, a bit of a trope. Does that automatically make it bad? It really depends on the assignment. Sometimes a cliche is exactly what an assignment calls for, but only you and your art director will know for sure.

That being said, putting in the hours doesn’t always mean that something better is going to come along. It very well might—even if the evolution is minute—but it’s not a guarantee. Still, if all that is accomplished with the extra effort is to prove the strength of that initial concept, then it was worthwhile. If nothing else, you go into the piece with that much more confidence.

So what do I, Steven Belledin, actually do? Well, frankly, my technique hasn’t changed much from my college days, as written above. I do a bunch of thumbs and build a sketch from my favorite one. Sometimes my favorite one was my first take. Sometimes it’s my tenth or twentieth.

Anyway, here are some pieces and a discussion of each in terms of which philosophy applied.

Mox Amber

This feels like the kind of thing that should have been a layup. But it wasn’t. It was the product of a lot of misfires. Ironically, the design of the object itself was not the issue. The problem was all about the presentation, and there was a lot of back and forth with my Art Director to nail down exactly what they wanted from me. Sometimes repeated rejection can be quite frustrating. In this case, it ended up being pretty rewarding. My design remained intact, and the composition we settled upon made for a better piece.

I don’t always keep my thumbnails, unfortunately. But I worked a couple of alternate versions up into finished sketches. At left was my first instinct, at right is the version that followed the assignment to the letter. There were a LOT of other thumbs developed, however, and ironically none of those came to represent the finished piece.

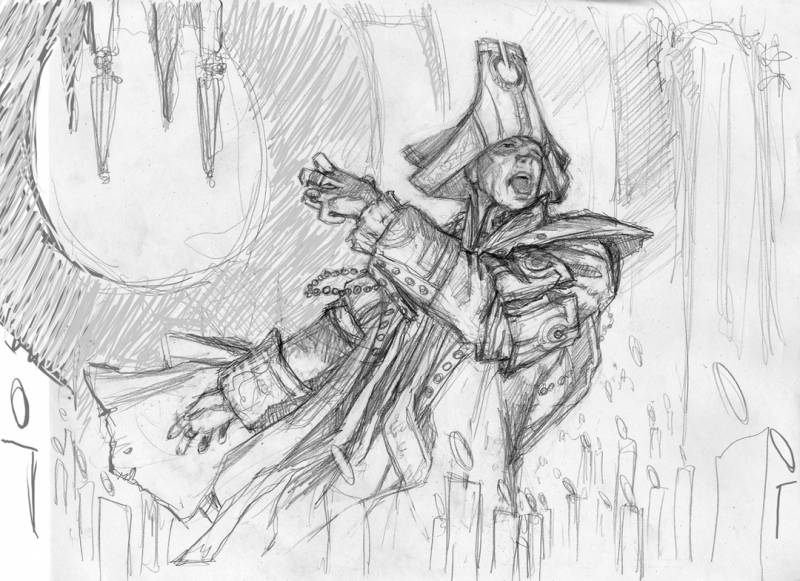

Mikaeus, the Lunarch

Despite first appearances, this was a hard fought piece, believe it or not. It’s not at all what I wanted it to be. But the client wants what the client wants.

Here was my first take, and it’s one I still find infinitely more interesting. However, it didn’t sell the character as the client thought of him, which was more a stoic, ceremonial religious figure, rather than a charismatic one. What they asked for and ultimately got is in keeping with their needs. But as the art description was written, this is what popped into my head, and boy do I still wish I got to paint it that way.

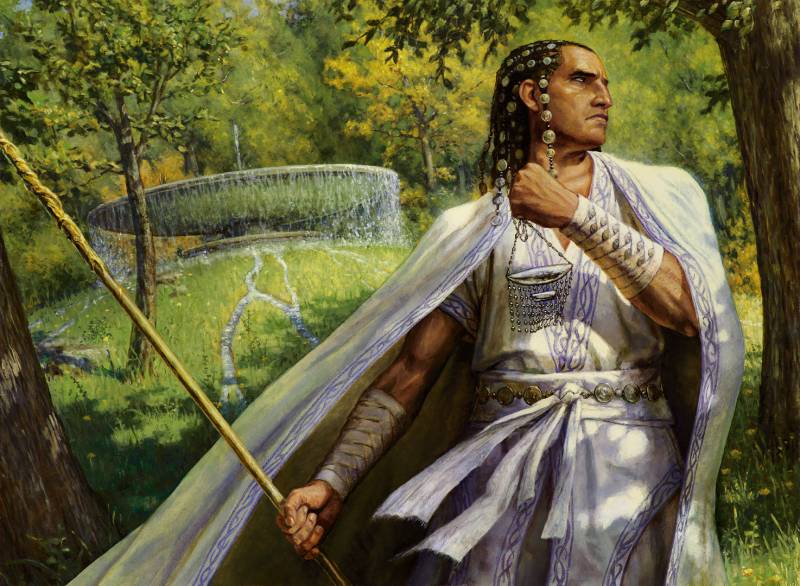

Cho-Manno, Revolutionary

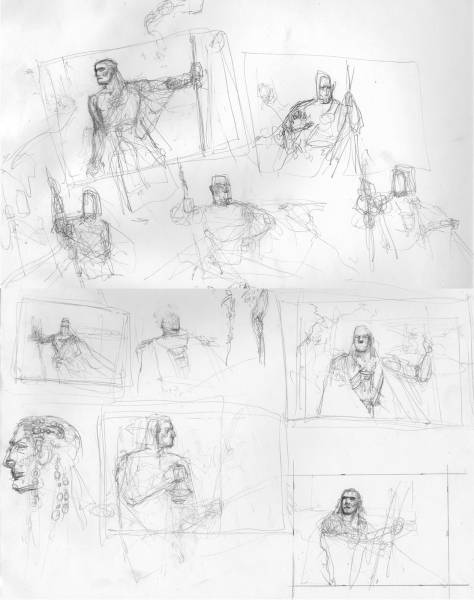

This piece took a TON of thumbnail drawings to arrive at, and represents one of the first times I’d been asked to paint a single-figure character study. Surprisingly, I found it really daunting.

While I arrived at this sketch, even this was revised (though admittedly in a minor way). But to get here required a lot of attempts to reinvent the wheel and to find just the right composition along the way.

Here is just a portion of the exploration I did on this piece. Several of these could have made for a fine image as well, but where my head was at for the first take is now lost to time. I just know for sure that where I landed wasn’t back at the beginning.

On other hand, there are these:

Prismatic Geoscope

A rare occasion where I took the art description and ignored a chunk of it because my gut instinct felt more interesting. Miraculously my Art Director agreed. I did supply them with a sketch more closely aligned to their version, but it was more as a safety precaution in case they didn’t like where I wanted to take the piece. I’d give you the sketch, but…it’s just more of what you see above.

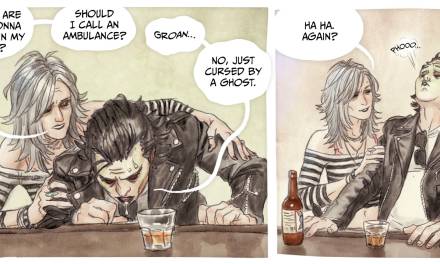

Treacherous Urge

Nailing down what the art director even wanted for this piece was the hard part and required a rare phone call to hash out some ideas. Honestly, I’m grateful that the Art Director was willing to take the time so I wasn’t doomed to throwing all kinds of things at the wall with no hope of knowing what actually did the job. In the end, he threw out a basic premise and I took it straight to a final sketch. No thumbnail or anything. I knew exactly what it needed to be. Only one revision was made: the marionette string was changed to barbed wire. I felt stupid for not having thought of it myself.

Surgical Extraction/ Surrender

(the Magic card’s name is “Surgical Extraction,” but I’ve never loved that title for the painting. Hence Surrender).

The short version of what I was asked to do for this piece was to illustrate the smoking skull and spine of a person having been ripped out and floating above them as they lay collapsed on the ground. After reading the art description, I immediately knew exactly what I was going to do with it. I did one thumbnail and one finished sketch based on that thumbnail. In my mind, considering the elements that needed to be included in the illustration, there was only one way this image even COULD be depicted. I was wrong, of course, as another artist, Greg Staples, did his own version for an alternate art version of the Magic card. So, I guess the truth is, this is the only way I COULD IMAGINE the image could be depicted. To me, downplaying the more visceral elements and presenting the image in a more peaceful, ceremonial way only amplified the horror. The Art Director seemed to agree.

For me, neither philosophy is something I’ll ever be able to adhere to. Sometimes, that first take ends up being the strongest. But only sometimes. And so I’ve kind of settled on this philosophy:

An image requires the amount of exploration that an image requires, and no two images are created equal.

But you don’t have to listen to me. There’s anything wrong with buying into either of the above philosophies and adhering to them. Part of becoming an artist or an illustrator is learning about yourself and what works for you. If you know that you’re prone to cliched takes on things, then adapting to that may be something you need to do. Or not. What works best for each of us is something we just have to figure out along the way.

Even then, because we don’t live in a vacuum, our processes may be affected by external factors—time crunch, the needs of the client, and the complexity of the challenge at hand. Some jobs are incredibly intricate in the stories they need to tell and the ideas they need to convey. And sometimes the out-of-the-box idea one has diligently worked at over a hundred thumbnails is dropped in favor of the idea one has discarded as low hanging fruit. So, flexibility is prudent.

A few last things:

I’ve found over the years that what works with one art director may not work with other art directors, meaning that some art directors consistently have responded to my first take on things when presented with it, while others consistently have chosen an alternate sketch. I don’t always know why that is, but the why is fairly unimportant. It’s just something I need be aware of when working with each individual art director.

Additionally, things that work for a client today, may not work for them tomorrow. Tastes change. When I first started doing work for Magic: the Gathering, my first instinct often gained traction and was approved. However, as time has gone on, my first take has been increasingly rejected and the exploration sessions in search of a version we’re all happy with have gotten longer and more difficult. The sweet spot is harder for me to reach. Such is life. Neither we as artists, nor our clients stay in the same place forever. We’re all constantly evolving.

Issues like the dueling philosophies I’ve discussed can be a frustrating feature of education (not to mention life). Many of us just want to know what the “right” way of doing something is and the introduction of competing ideas can be difficult to navigate since they buck the notion of a “right” way altogether. We must, each of us, instead endeavor to find our own “right” way. And so the rules and philosophies each of us wind up working by will—in the end—be our own, and will change and evolve along with us.

From my take of this subject it seems your first thumbnail or as many as it takes depends on both you and the director agreeing on the piece. If you have a strong-willed art director who has a specific point of view of what the piece is going to look like there’s not much you as the artist are going to do to change that. If the director is more easy-going or open-minded then the art director will work with you. Then there’s the art director that is every artist’s dream and says, “Do what ever you want. It’s OK.” (Pray to the art gods for this one!)

It also depends on the chemistry you have with the art director. If you know of some art director you can creatively ‘click’ with you usually spark one another with more creative ideas and usually arrive at the piece with mutual collaboration, the ideal dream scenario for the artist. (Too bad they don’t have a business-relationship website for artist and art director to “hook-up! That would be funny. “Hi, I am an art director seeking an artist who bends to my will and does what I say, but has an open mind, is creative, and has the job done by yesterday. The artist: “Hi, I’m a gifted artist looking for a mutual gifted art director, but understands that MY vision of an art piece is the RIGHT one and allows me all the time I need to finish the work with pay in ADVANCE. And I love long walks on the beach… )

(Heeeyy! There’s an idea here!) 😉

As an artist myself, I would love to paint and draw the piece the way I see it. The problem here lies in am I “locked-in” to my point of view? If you see it only one way then you’re going to butt heads with an art director, especially if they’re strong-willed too. If the art director is more easy-going then he/she will allow you to do what you want. So it depends on your temperament, too. Are you strong-willed or easy-going? The more strong-willed “I must have it my way” the more head butting. Too much easy-going attitude and you won’t show your vision.

Your job as an artist is to fulfill the job for the client and it’s technically their vision not yours. However, it has to be some where in the middle. There has to be a marriage of the both ideas from the artist and art director. (There’s that relationship concept, again.) It’s easier if both the artist and the art director are open-minded to each other. That being said, as an artist I think you have to be adaptable to the needs of the client while still staying true to yourself. Not an easy thing to do, I know.

The way I see this subject sounds to me like a business-relationship issue. It seems to me artists as well as art directors need to look at business-relationships like personal relationships. Where there’s a give-n-take and an open mind of both ideas from each other and meet somewhere down the middle. And that’s my “two cents…”

Thank you for the insightful article!

There’s a lot of truth to what you’ve written, and I think you’re right. The only thing I’d add is that ideally, we’re not completely guns for hire. We’re hired for what we bring to the table, not just our ability to fulfill the client’s wishes. Whether one’s gut instinct on an image jives with the client’s needs is, of course, going to vary on a case by case basis, but what we as artists even put forth for the client’s consideration still has to pass our own sniff test, so to speak. And that’s where these philosophies start to really kick in. Not every art director even gets to see my initial take on something, because…well sometimes it’s really bad. Other times, it’s incredibly difficult to get past the strength of the initial notion. Regardless, I always found some of the points of view of my various professors and the guest artists they brought in to be somewhat frustrating because they were strident in their convictions that their way was synonymous with best practices. The reality is so much mushier.

Thanks for reading! And commenting!

Great piece, Steve. For me this is part of a much bigger dilemma. I think in many ways your first idea is always your “strongest” in that it probably represents what you are most interested in, what you do naturally, and therefore what you will be able to execute well. On the other hand, in the objective world, it’s likely that stronger ideas come from iteration and collaboration. But working that way is distasteful in many ways, for some artists. To me the broader issue is artistic growth. A lot of really great artists keep developing the same kind of work, and get really great at it. Others want to learn to do new, different things from what they have done in the past.

Thanks for that, Chris. I totally get what you’re saying, yeah. I think you’re right that collaboration can absolutely yield stronger ideas. I’ve also had it go the other way, unfortunately. More than once. Those ended up not being portfolio pieces, but the client wants what the client wants.

Also, good notes on the issue of artistic growth. I guess I was writing under the assumption that the reader wanted to push themselves as it’s something I try and do myself (though sometimes quite unsuccessfully). Getting out of my comfort zone is exciting, and a lot of times that’s built into my thinking process. I guess the problem for me is that direction I’m unconsciously pushing myself in seems counter to what my clients clearly need right now, and so I’ve answered that with personal work and revisiting other mediums that I haven’t used in a really long time.

Anyway, I probably should have included at least some mention of an alternate point of view and desire. Some folks really do just want to learn to master a kind of work and do that for the rest of their lives, which is great. And that can affect one’s philosophy or lack thereof.

Here’s a fun idea/challenge: draw 10 thumbnails, each of a completely different project, so they’re not based on eachother. This way you’re drawing 10 first ideas in a row.

Out of those 10, will there be at least one that would be the right one if you explored more thumbnails within it? And if practiced enough would doing this improve your chances of getting it right on the first go more often?

I usually work on lots of thumbnails, and I don’t find out that the first or the last one are the best consistently, maybe they’re sometimes, but the important thing, I think, is to push the design further while you’re working on the composition, sometimes I feel like I’m struggling, but end up with some good compositions after hitting a wall.

I’ve heard some artists say that they like when the painting is easy, it means they’re on to something good from the start, and while that may be true, the opposite works out just as well, at least for me, I guess it’s the same thing with compositions.