These past few months have seen a handful of questions raised about my creative process and how to go about initiating and/or maintaining interest in a work of art as I move deep into its long process of execution. In nearly everyone of these cases, I found myself turning to a wonderful quote attributed to Howard Pyle:

Throw your heart into the picture and then jump in after it.

It is a wonderful, simplified way to describe a process which is nearly necessary for all great works, but cannot be detailed, taught, nor duplicated through rules, rituals, studies, etc. It is one which must be experienced. And experienced again and again on a personal level.

Much like learning to swim, one must enter the water and take the temperature of the medium and feel how it flows between your finger tips. No book will ever prepare you for the real sensations. Flailing about is guaranteed, as well as choking on mouthfuls of water, before one eventually glides smoothly through the medium, effortlessly manipulating its flows after hundreds of immersions. Such it is with art.

Far too often I see new and young artists hoping and thinking they will master their medium, their compositions, their stories in the first handful of tries. Thinking there must be a secret to unlock which will score them great and immediate success. Luckily a few may experience such riches, but 99% of the time it was indeed luck, and the ability to turn a form, nail the anatomy, render that lighting effect on one job, and the next, requires taking numerous deep, penetrating, struggling swims back into the water.

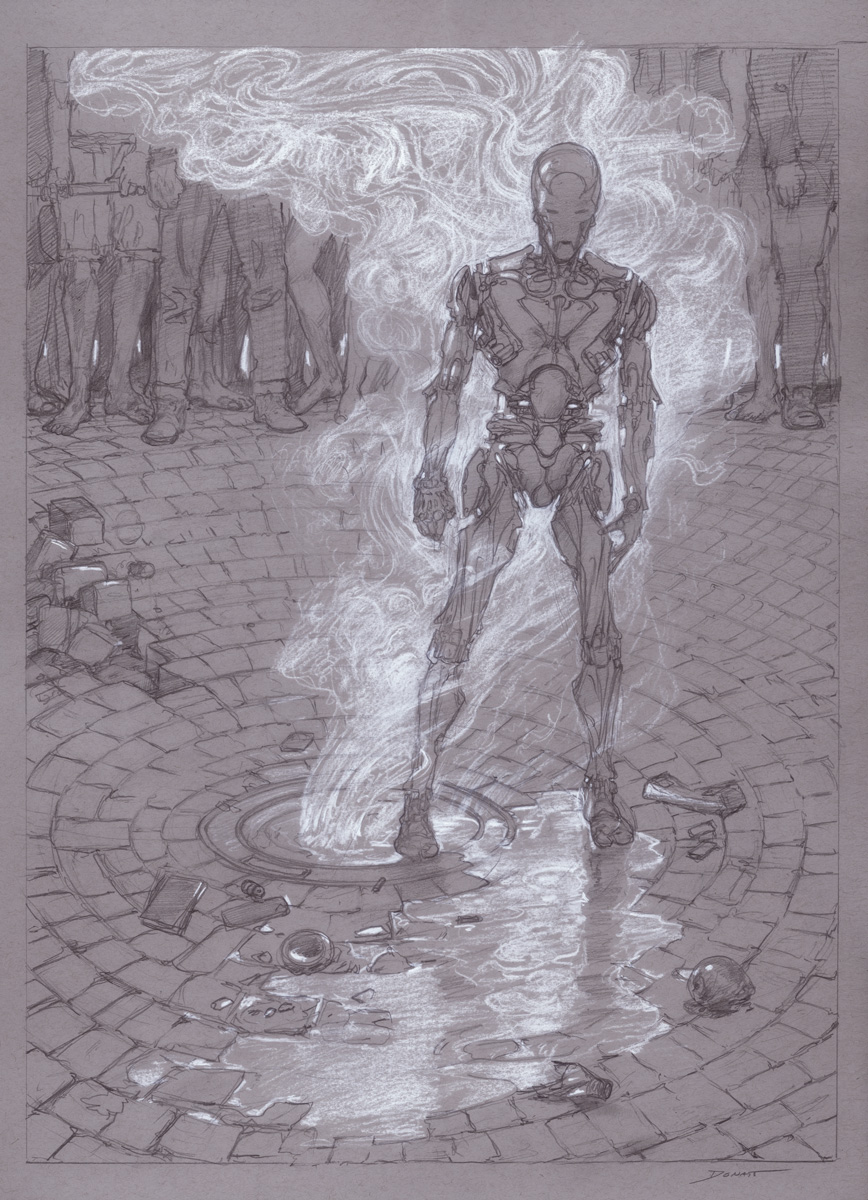

There are many ways to interpret Pyle’s quote, but here I wish to call attention to this water analogy and how we generate interest and passion for our works. The concept here is not to ‘think’, but to ‘feel’. Act first, explain later. Jump into the water, not wade.

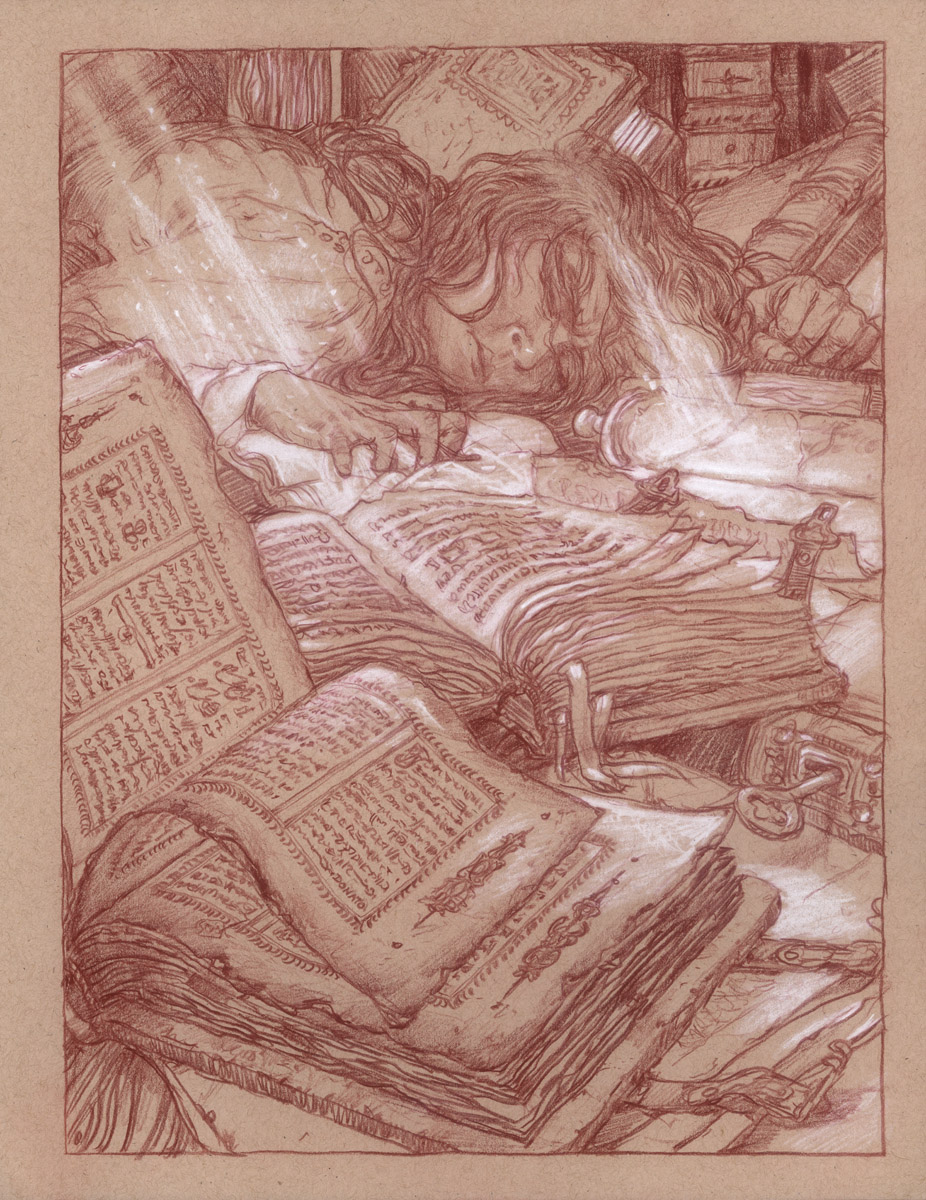

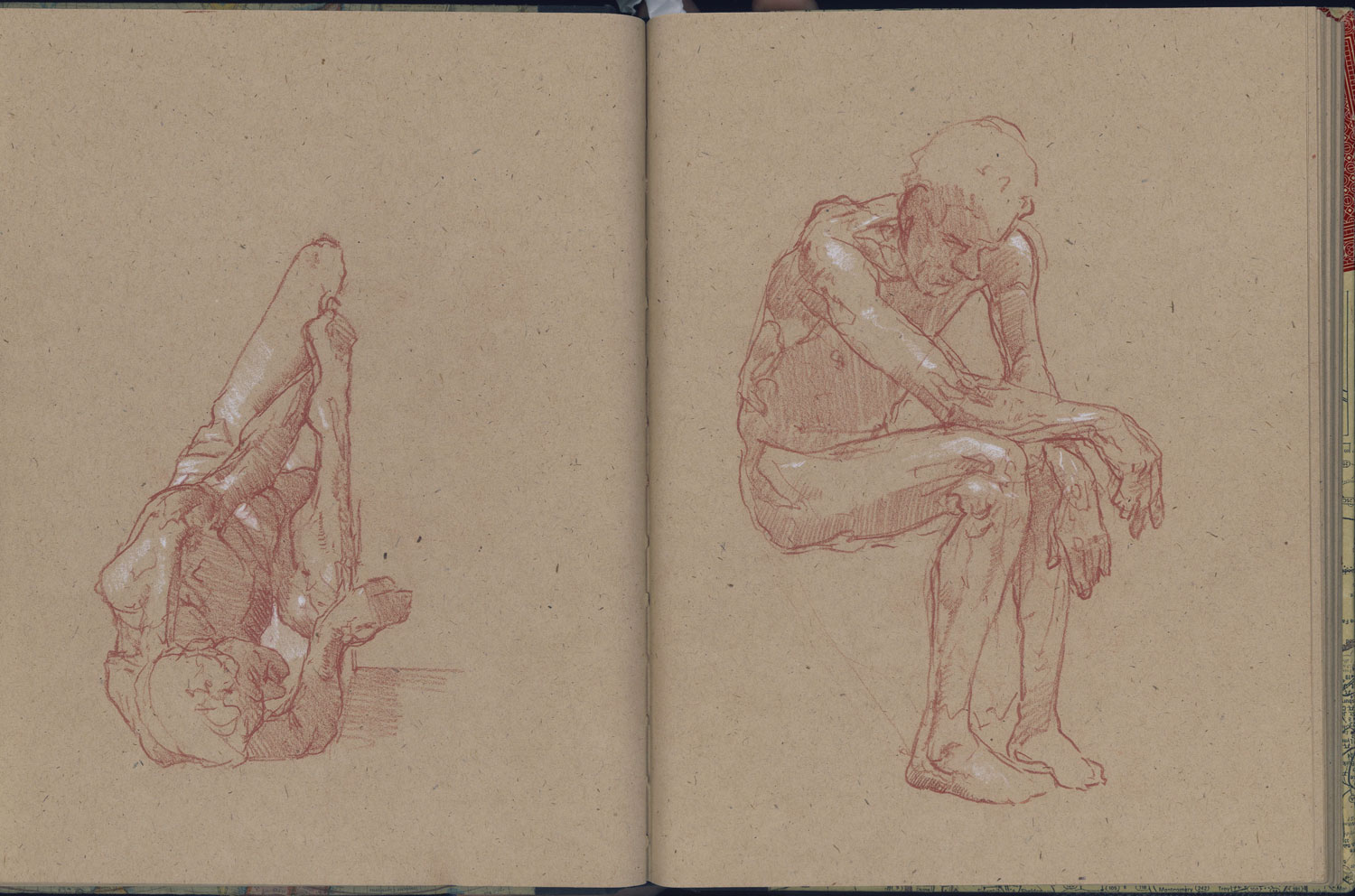

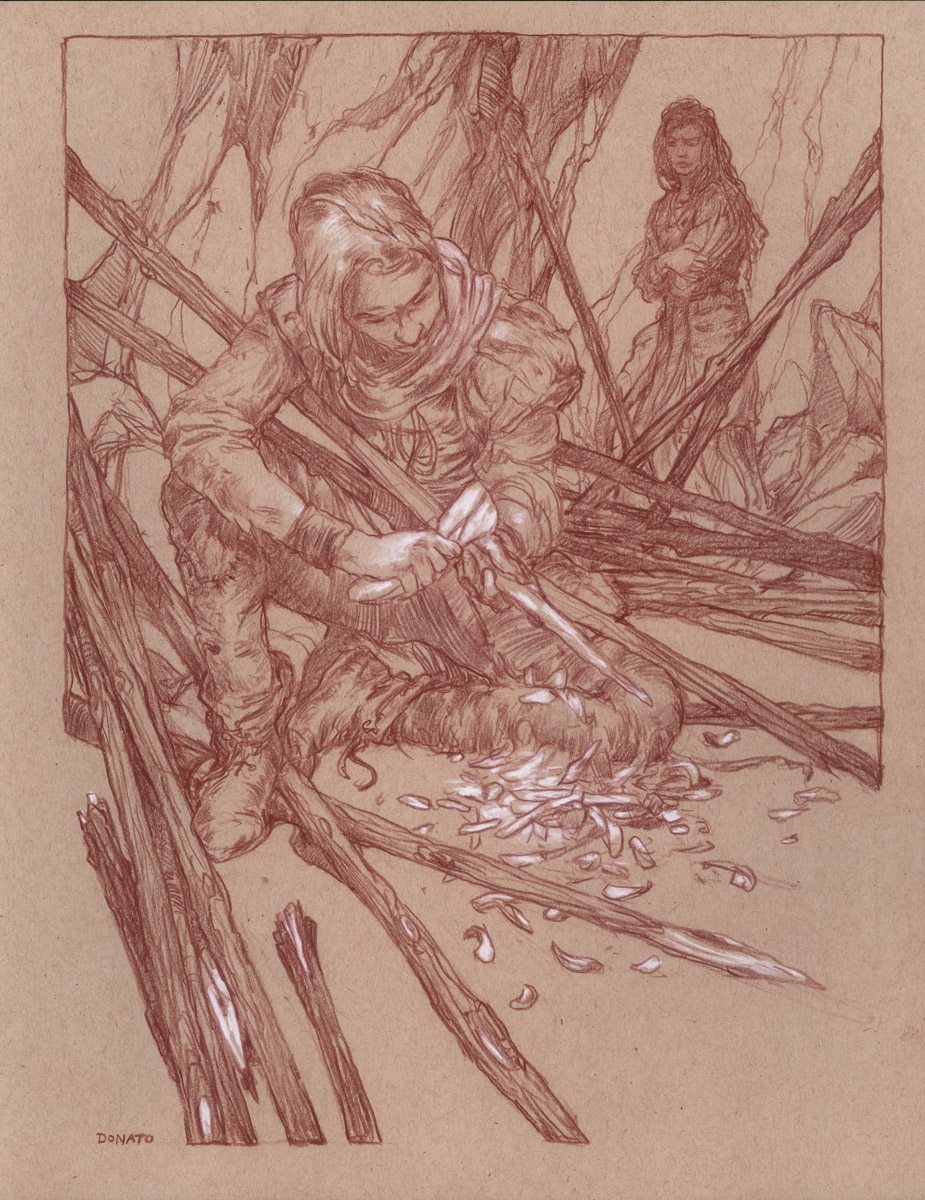

The reasoning behind this is to force one’s creative hand, challenge the mind to make sense of what you are feeling in a piece as you work out those scribbles, those shapes, those inspired ideas. Tap into that which speaks to your passion, not just your knowledge. Draw the model as you feel it, not only as you see it.

This is a feat that becomes clearer the more one practices and executes work, conquering the technical challenges before us. Dive in, swallow some water, and feel how the mediums acts. And do it again.

Do you recall ever sitting deep in a pool, holding your breath while you watched the play of light upon the surfaces around you? Light refracting off the underside of the surface, rippling waves of light on your hands, silver bubbles of air rising to the surface? How sublime those feelings are, no? Did you experience those the first time you jumped in the water? The tenth? The hundreth? Only after master of a certain level of swimming could we begin to appreciate another level of awareness.

Pyle was an incredible draftsman, painter and composer. His images are easily some of the best in the history of art, but acting as he does from the heart in the initial phases of image making did not preclude him from turning on that precision thinking to complete an idea, an issue many critics and artists teach us to ignore in the pursuit of true emotion projection. Pyle wants us to master the medium so that we can experience the sublime more deeply through an integration of emotion and knowledge.

The beautiful details and sensitivity of the natural world become all that more celebrated when one has a deep, passionate emotional framework upon which to hang the artistic motivations.

The ‘jump in after it’ portion of that quote is, to me, a set of directions that all rules and laws of image making are to be brought in service of the emotional idea, and not the other way around.

Service your heart first and your labors will become a work of passion.

대전출장마사지로 쉽고 간편하게 집에서 경험해볼 수 있습니다.