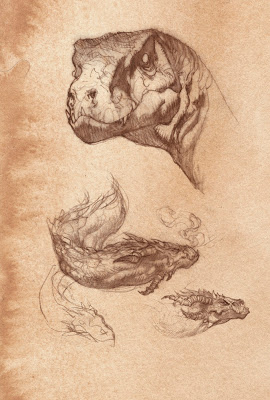

While I love studying the creatures of this world for clues on how to make a fantastic creature feel like they could exist in it, I think that by making dinosaurs and dragons altogether interchangeable in our work, we are giving up on all the possibilities which each contains individually and for which they have been historically used in fantasy.

Tolkien makes a compelling case for a distinction between dragons and dinosaurs in his essay, On Faerie Stories:

I was introduced to zoology and palaeontology (“for children’’) quite as early as to Faerie. I saw pictures of living beasts and of true (so I was told) prehistoric animals. I liked the “prehistoric” animals best: they had at least lived long ago, and hypothesis (based on somewhat slender evidence) cannot avoid a gleam of fantasy. But I did not like being told that these creatures were “dragons.” I can still re-feel the irritation that I felt in childhood at assertions of instructive relatives (or their gift-books) such as these: “snowflakes are fairy jewels,” or “are more beautiful than fairy jewels”; “the marvels of the ocean depths are more wonderful than fairyland.”

Children expect the differences they feel but cannot analyse to be explained by their elders, or at least recognized, not to be ignored or denied. I was keenly alive to the beauty of “Real things,” but it seemed to me quibbling to confuse this with the wonder of “Other things.” I was eager to study Nature, actually more eager than I was to read most fairy- stories; but I did not want to be quibbled into Science and cheated out of Faerie by people who seemed to assume that by some kind of original sin I should prefer fairy-tales, but according to some kind of new religion I ought to be induced to like science. Nature is no doubt a life-study, or a study for eternity (for those so gifted); but there is a part of man which is not “Nature,” and which therefore is not obliged to study it, and is, in fact, wholly unsatisfied by it.

-J.R.R Tolkien from On Faerie Stories

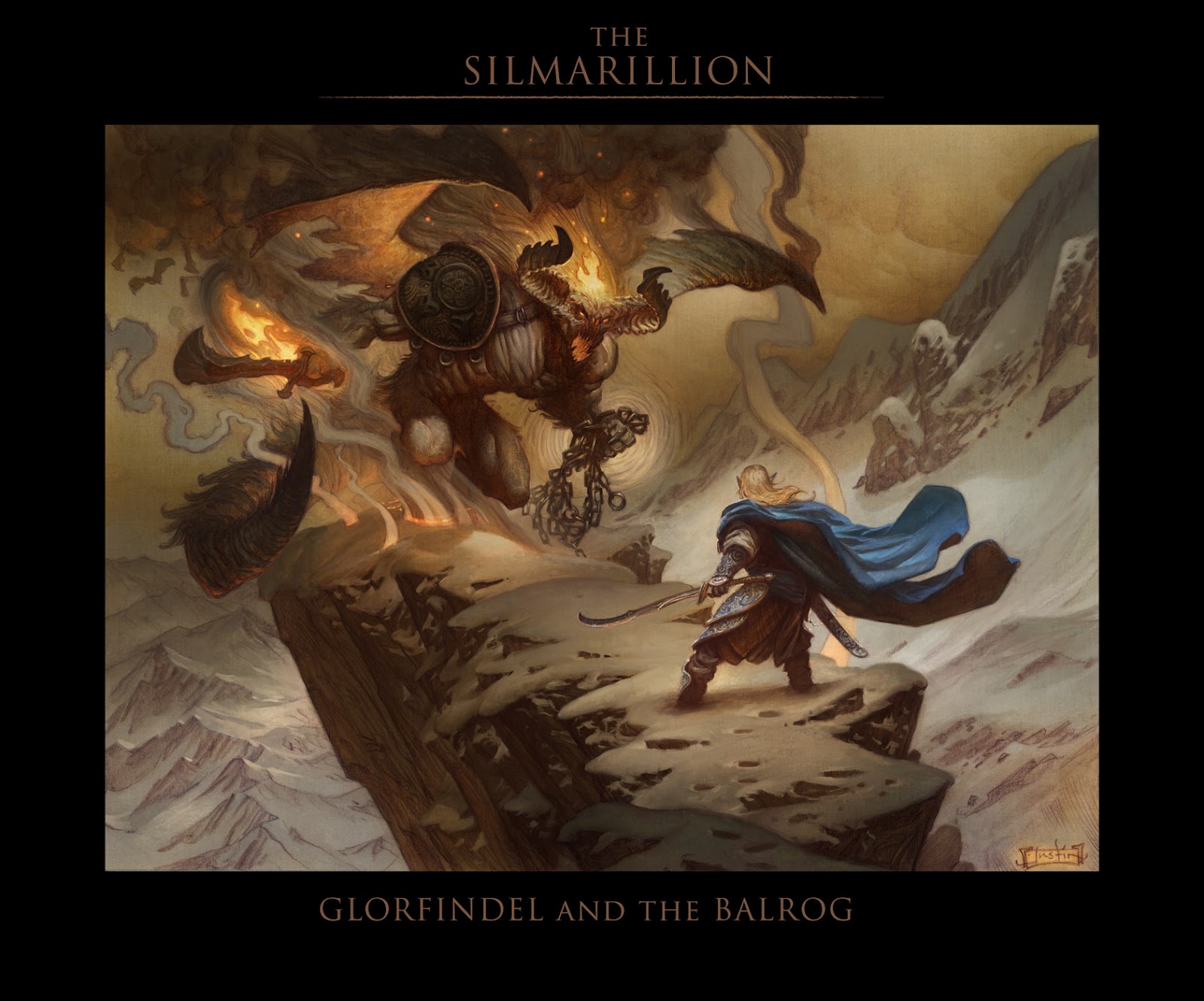

In Tolkien’s own Smaug, the dragon offers more than just a physical threat of violence, he offers a personification of greed (and a distinctly aristocratic greed, which refuses to share or recirculate wealth, that only consumes and consumes and keeps it in dark halls, leading to the ruin of the nation.)

In John Gardner’s Grendel, the Dragon is even more a philosophical threat over a physical one. The dragon reveals a set of philosophical beliefs to Grendel, and it is these that Grendel wrestles with, and is ultimately overcome by. This leads him to choose to become, and even embrace his position as, the villain in the Shaper’s story. The dragon in Grendel personifies a deeply nihilistic view of the world: his final arguments about the purpose of life being that all human values are baseless and that everything we do will be made irrelevant. His best advice to Grendel is to “seek out gold and sit on it.” As nothing really matters anyway.

Gardner uses the imagery and the archetype of the dragon to convey how coldly-calcuating, threatening and dangerous the idea is, and this belief is ultimately played out through Grendel’s own final meeting with Beowulf.

This type of symbolism in dragons offers something far more than a struggle of man vs. nature. It does what fantasy does best, it offers physical examples of man’s internal struggles. And offers us a wealth of other conflicts, both external and internal.

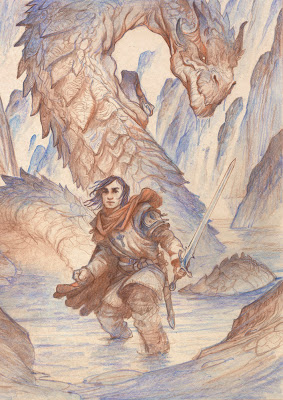

If we agree that dragons in fantasy should be something more than just animals, that they have an intelligence equal to or greater than humans, then we should seek to imbue them with an equal amount of human personality.

So consider your dragons. What is really inside them and how can you show it on the outside?

cool post!! i like thei dea of dragons being more than just beasts.i remember reading a fantasy book ( cant remember wich one) where dragons were most of the time disguised as people

very good comment

There are certainly plenty of wonderfully drawn and painted versions of Smaug, many of which I deeply admire – but at the same time, very few of them look to me like they could hold the conversation with Bilbo… that voice, that attitude which you've put so well into words – a very tricky thing to capture, to be sure!

Great advice and great thoughts to ponder, Justin.

Great post and good advice! I love the idea of a dragon being a physical example of internal struggle. I agree great creature design mixes something human and emotional with the fantastical, and a good understanding of nature. The challenge for the artist is to find the right balance.

The quote from Tolkien is wonderful, there is a part of us that looks for things that are beyond what is natural.

Excellent post. I love Tolkien's thought on things beyond what we learn in nature things perhaps even beyond our imagination. Having just reread The Hobbit I was struck by the notion in the story that just talking to Smaug was not safe. Biblo was playing a dangerous game when he riddles with Smaug as to what his name is and who he might be. I believe it's Gandalf who says others have had their brains fuddled or been seduced by conversations with dragons. Smaug suggests the tempting serpent in Eden. And Biblo just nearly escapes being fried to a crisp at the end of his little talk with the dragon.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts on real creatures and those of fantasy, Justin.

Best Wishes,

Aaron

Excellent post. I love Tolkien’s thought on things beyond what we learn in nature things perhaps even beyond our imagination. Having just reread The Hobbit I was struck by the notion in the story that just talking to Smaug was not safe. Biblo was playing a dangerous game when he riddles with Smaug as to what his name is and who he might be. I believe it’s Gandalf who says others have had their brains fuddled or been seduced by conversations with dragons. Smaug suggests the tempting serpent in Eden. And Biblo just nearly escapes being fried to a crisp at the end of his little talk with the dragon.