I’d also like to thank the generous Tim Paul for illustrating yet another of these posts. His ideas for this one really cracked me up. I was going to feel guilty, since I’m the one who wrote the article on working for free, but in trade I am designing the type for his Xmas card. (I love bartering.)

When Dan Dos Santos originally asked me to be a contributor on Muddy Colors, I was very excited, because there are a lot of myths and misconceptions surrounding the business of illustration and art direction, and I really wanted to pull the curtain back. I found myself having the same conversations with artists over and over again, and I realized there were not enough places to read about these issues online. It makes me so happy to be hearing from so many artists that these posts, and all the fabulous posts Jon is writing over at ArtOrder, are helping to shed some light on our business.

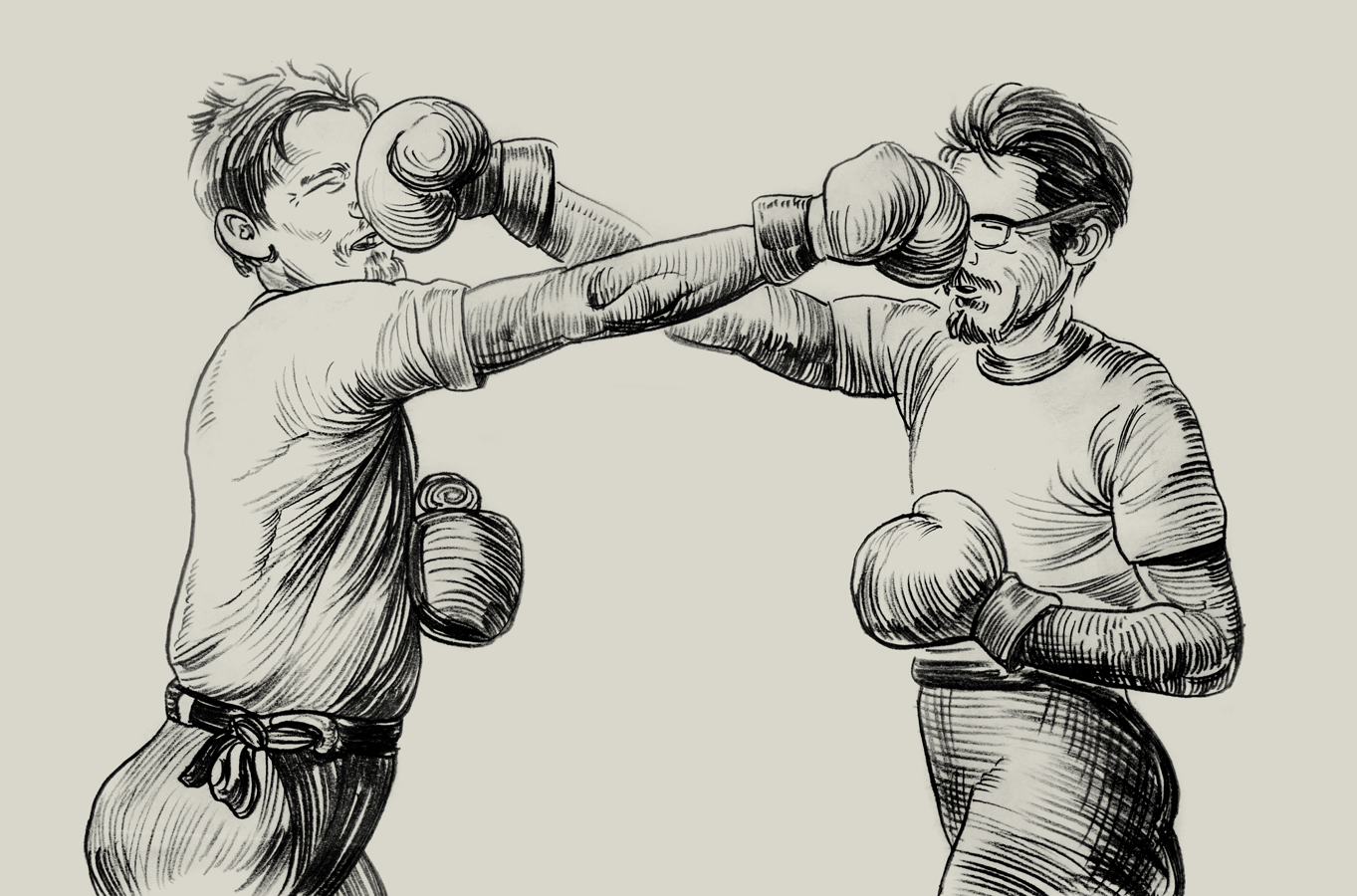

I believe that the answer to most problems is almost always better communication. As an art director, translating between editorial/corporate (words) and artists (pictures) is the core of my job, and I have learned that these two species do not speak even remotely similar languages. The quickest and best way I have found to foster cooperation between these two alien species is to raise the empathy level between them. When you have empathy for another person, when you can understand their motivations, then you can respect their position (even if you do not agree with it) and you can work to find common ground. This is what I do daily as an AD. (And Tim’s illustration below perfectly illustrates how that feels much of the time.)

In an ideal world, corporate and art would have this empathy and perspective, which would result in a better community, and better work for everyone. When our bosses want more for less, we tell them why that’s not reasonable. We have won many of these battles. In most cases there’s not even a battle to be fought—just a message to get to the other side and have understood. We educate our companies of the artists point of view, and they are, in most cases, able to accommodate. We find a middle ground that works to protect both business concerns and creative concerns. That’s why I am happy to have these conversations with artists over and over, explaining the side of things they don’t get to experience. That’s why I spend so much time writing these posts. And that’s why it has saddened me to see a great idea like artPACT occasionally take turns into very bitter territory. I support a lot of what they stand for because, like every other AD I know, I love to get the absolute best deal for our artists. However, over and over again in comments and on social media from many sources, I am too often seeing the AD blamed for company policy over which they have little or no control. I can’t condone public shaming in general, but especially not when it’s supporting misconceptions about how the industry operates.

Let’s take a step back and try to see the issues without bitterness. Does it make sense that an AD would want to have anything other than perfectly happy artists? Most often it is the AD that is railing against, and trying to change, the very same policies that infuriate artists.

Call me a hopeless optimist, but as the “monkey in the middle” in a lot of ways, I really believe we can work together to iron out misunderstandings, as well as make positive changes in the industry together. It shocks me to see artists consider ADs more on the side of a company than on the side of artists. We call artists “our artists” because they are our team, we need them, and we want to take care of them. I can’t speak for every AD in the world, but I know almost every AD working in the SFF world, and I can be completely confident in saying that we want the best for you and work hard to get it. We are not the enemy…maybe we sleep with the enemy sometimes, or just make out out a little bit, but we always want to protect our artists at the same time. ADs and the companies they work for are separate entities, and need to be judged as such.

For example: I have publicly posted that my company is pretty awful at getting people paid sometimes. It’s not on purpose, it’s just outdated bureaucracy. I know this, and as an AD I go out of my way to make sure my artists are getting paid. I chase payments, I tell artists to make sure to not feel bad about letting me know if something has gone wrong, and I have even spent hours and hours at work developing a better system for the company as a whole to adopt for paying artists. It will get through eventually, but making change in a huge company has taken over a year so far. So I support artists organizing, and speaking out about the conditions under which they will not work. If artPACT wants to give my company a bad rating for payment processing, please do! I can use that discussion to affect change. You’re working with me. But counting me, the AD, as responsible for that payment system’s malfunction is counterproductive. And vilifying a person for policies they have no control over just fosters hostility in our community.

Less blame, more constructive criticism.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned in my years as an AD, it’s that change comes from communication, understanding, and cooperation. The SFF art scene is one of the most nurturing and welcoming scenes in the entire art world. I feel like we owe that to ADs like Irene Gallo and Jon Schindehette and many other ADs and artists. Of course there is room for improvement, but we can’t let what is good be torn down in the attempt to change for the better.

And since I feel like the best way to mend fences is through humor, here’s a Quiz I’ve designed to equally amuse and educate. The answers are in white under each question. Try to take an honest guess, then highlight the space after “answer” with your cursor to reveal the answer:

LP: When I hire an artist I hope for the best and expect the worst. For each and every job I have to ask myself “If everything goes wrong with this project, and the artist turns in the level of their worst work here, will I be able to deal with that?” If I have a lot of time on a commission then often I will take a chance on that new artist I’ve had my eye on. If things go south, there’s time to do a few extra rounds of revisions or try something else. When it’s a high-pressure job, though, I’m going to go with someone I’ve worked with before.

MS: Every AD I know is willing to put in the extra time to take a chance on someone, but we can’t take chances every time. What if we hire you and we get your worst day, and on a tight deadline? This isn’t about pessimistic, it is simply realistic. We have all had that project go south and had to go extra rounds or in the worst cases pull in a ringer or even make changes ourselves . It costs time and money. It frustrates the artist, and is emotionally challenging for them and us to get things done. That’s why I tend to hire off of portfolios where I love every single piece.

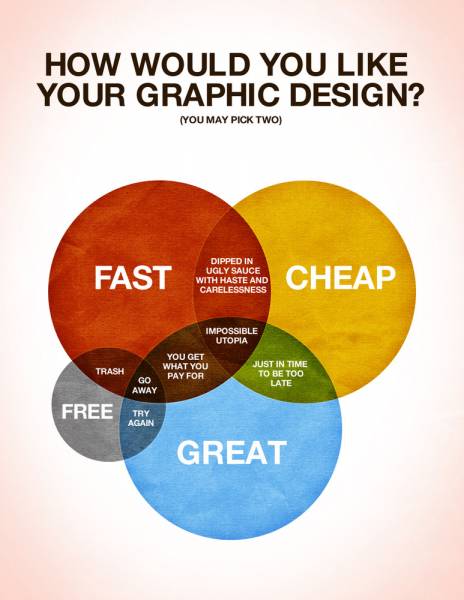

LP: Although I jest about hiring artists that bake me pie, in truth, my personal relationship with an artist has very little to do with hiring them. Clearly it helps to know the person is pleasant to work with (remember the “good/nice/on time” venn?). I’m also not going to hire someone whose work I don’t like. I usually pick 2-3 artists to pitch for every project. Sure, I control the options, but it’s not me who gets the final say. Before I commission an artist, my editor, publisher, and usually the author need to be on board. I have a long list of artists in my head I am dying to work with, but for some reason or another, I just can’t get them approved.

MS: I’m lucky, there are so many great artists out there I can usually put together a list of ones I like with confidence that some number of them will get approved by our clients. That’s in the 73% of the time my job is in an ideal world. The other 27% of the time the deadlines we are given are impossible to put it mildly, and leave me without time to negotiate, so reliability becomes a big factor. The truth is everyone I know who buys art, from corporations to individuals, wants it fast, cheap, and good. I tell them they can pick two. And even THEN I know that I may have to put in extra time either working with the artist or finding other ways to get the job done.

LP: I know artists see my Facebook feed and see me hanging out with other ADs at cons, going to the Society of Illustrators for lunch, and going to art events and openings. Very glamorous, I know. What you don’t see is all the late nights I’m sitting at my desk until 10-11pm simply answering emails. Trust me, they’re the norm, not the exception. I don’t like to post about it because no one likes to hear me whine, and also, I do it out of love of my job, not because I’m looking for pity. Also, as frustrating as it is for you not to hear from me, it’s twice as frustrating for me to not be able to get an answer from editors that sit 5 feet away from me. Approval chasing is the most annoying part of my job, hands down.

MS: Waiting on approval is the number one issue I deal with in scheduling. As an artist myself, I can’t help but be a bit of an empath and I feel the frustration on both sides when I have to talk to artists week after week on a project that has become low priority for a client and I’m just saying “hang on.” I am currently working with Jon Schindehette on a new system that will help us get approvals at Treehouse easier and faster. A lot of this will involve communicating the same need for empathy and understanding Lauren spoke about above. We know you guys, especially those who work hard and count on freelance as their only income, need some clarity on schedules for stability, and we’re trying to get that done. As Lauren said above, when the chain of command is long (and they almost always are) this just takes time.

LP: Although I have a little wiggle room if thing are a rush, or if we go through an excessive amount of revisions, I do have to get every dollar I spend on a cover approved. If I spend too much on a book, it could very easily tank the book, and mean that an author doesn’t get to write any more books for us. It’s my job to protect my artists and make sure they’re being paid as well as possible—but at the same time it’s the editor’s job to make sure the book ends up in the black, and it’s the publisher’s job to make sure the company stays afloat. If Orbit goes under, then I can’t pay any artists. Sometimes I have to ask artists if they’ll work for less than I know they’re worth. Sometimes they can’t, and sometimes they can. I trust the artist will be honest with me—if they just can’t take on a lower-priced commission, I hope they just say so. I certainly don’t want them agreeing to a price and then being bitter about it. I’m not ever going to hold it against someone if they turn down a commission from me, because of price, schedule, or anything else.

MS: I’m lucky again, we pay pretty well. but not everyone does or can. That said every AD I know went to art school and has working artists as their core and extended friend group. Nothing, nothing, gives us more pleasure than paying people well for their craft. Sadly I have seen posts online about an AD who, for the simple fact that they are the messenger for company policy, are called a “joke” or “terrible” or worse. If you think we like telling anyone we can’t give them more money for making their art, you’re not really thinking the situation through realistically. Offering a great rate will get us the best artists, and the best work out of the artists with whom we get to work. Getting you good rates makes our jobs easier so we have every incentive to do so.

If I were to suggest a path forward for those like artPACT who seek to affect positive change, I would say to open a dialogue with your AD and find out what they need to help you. Tell us what’s working, what’s not. If enough artists start turning down lower commissions at any one company, maybe that’s enough ammunition for the AD to go back and tell corporate that they can’t get the artists they want and need to raise their rates. But every company is different, and every bureaucracy has different pressure points. So do ask your AD how you can help, and if they have time to push on that pressure point, you will get a fair response. That’s good communication and will help everyone.

LP: This is a hard number to give concrete evidence for, but look at it this way—I guarantee you that the companies that pay the lowest commission rates also pay the lowest AD salaries. And the ADs that work for those companies do it because they love what they do, not because they’re raking in the dough.

There are industries in the SFF genre that make more money than others, and some, like gaming, can only stay afloat by making a lot of art for minimal cost per piece. Many artists use that system to climb up the ladder to higher commissions for other companies and industries. If you feel the rate is too low for you, then don’t accept those commissions. If enough artists turn down the commissions, and the company has money, then they will probably try to raise rates eventually. Unfortunately not every company has the profit margins to do that.

MS: Lauren is right, there are a lot of factors that go into this, and I can’t speak for every AD in every industry or in every state. But it’s true, ADs generally have a salary and a reliable, stable income. In order for artists to do the same, we have to work quickly enough to get a good “hourly” while still producing work that will get approved and that we want in our portfolio. However, some projects take more time for the artist, and some even require that I, as an AD, step in and do some of the art fixes myself. (Huge disclaimer: I only ever do that if I can’t reach the artist for a very fast turnaround and I always get the artist to approve any changes I make.) What I can tell you for sure is that on any given project, my take home pay is both worth my time and measurably less than the artist.

LP: I go out of my way to give as much detail as possible to an artist, so they know where they do and don’t have artistic license. I tell them exactly what needs to be in there to check all the boxes for target audience, genre checkpoints, story details, etc. I’m also seeing sketch stages along the way, and course-correcting. Usually I have minimal revisions as we get close to final. Unfortunately, no matter how many stages I show them, my approvers very often have a change to make that I couldn’t anticipate. Maybe the manuscript came in and it’s a much darker book. Maybe the author rewrote important character details. And thank god I almost never have to deal with big IPs and licenses. Art for a license like Star Wars needs to be perfect, or the license rejects the piece with little thought for all the work that has gone into it. There is no compromise when drawing an X-wing. It’s going to keep getting sent back for revisions until it’s right, or the piece will eventually just be killed. There’s no room for debate there.

MS: Working with IPs and Licenses is a unique challenge. It means there are certain requirements we have for the kinds of illustrators we hire. Most common is a certain look, a certain level of finish, or a style. In some cases we really need artists who know the property because our clients are the absolute experts on the game in question and any deviation from the design in the game will stand out to them like a sore thumb. I know that if I turn in an image for review and the character is wearing the wrong coat, or the spaceship is too long, it not only means more rounds of reviews, but it means an unhappy client. Fortunately, there are enough great artists who love the properties I hire for. I wish I could hire everyone, and sometimes I get a schedule with enough room to take chances on someone with great work who doesn’t know my IP. It still takes longer to finish, but it is gratifying to take that chance and end up with a great product.

LP: Of course an AD is expected to have good taste, and yes, we generally have crack photoshop skills, but the real talent that makes an AD is diplomacy. We are like the translators in the UN, stuck in the middle of the General Assembly floor trying to diplomatically translate a fight between two sovereign states determined to go to war. We are argonauts constantly navigating the rough seas between Corporate Scylla and Artist Charybdis. (OK, I’m getting dramatic here.) We’re the ultimate people pleasers, yet we’re pretty much always the fall guy when shit hits the fan.

MS: I’m pretty sure I studied more Latin than Lauren and, man, that’s a great analogy. What we deal with more than art, more than email, is humans. Artists and our bosses, all human, all with the desire for a communication style that works for them. You can say things to anyone in ways that they’ll get, and ways that they won’t, and it’s never the same for any two individuals. So it’s up to us to learn people, and find ways to communicate with them so that they want the result that will get the best product in the end. As Lauren said, artists and corporate don’t speak the same language, and translation can be a bitch, but when it works it’s. the. best.

Answer: Well, all of the above, but mostly d) Not getting to hire artists who’s work you love

LP: Even with all the challenges and rough things about being an AD, I still say the worst thing about my job is not being able to hire every artist I want to. There are artists who are so good, and so deserving of work, yet that perfect project just doesn’t come up. Or it does, and I can’t get my first choices approved. There are artists I have wanted to commission for the entire 5 years I have been at Orbit, that I would be thrilled to collaborate with, but I haven’t been able to make it work. I tell artists that sometimes, that I really want to work with them, and I don’t think they actually believe me.

MS: We have a limited amount of art to hire out with deadline that vary from months, to weeks, to “oh shit, I need it tomorrow.” Even in a banner year we can’t hire every qualified person. It’s like ivy-league applications out here, we say no to so many obviously qualified people because there are just too many to hire them all. I have a healthy list of artists who I pitch on almost every project that don’t get approved. But I’m patient, their day will come, and that will be a fabulous day because they have worked hard to develop an amazing look, and hiring them to do it is incredibly gratifying.

LP: Again, I can only speak for myself here, but collaboration is the drug that keeps me going. Otherwise I’d simply burn out. It’s not awards or publication—although it’s awesome to work on a project that wins an award for an artist, or gets them published for the first time. Seeing my covers in stores is more grief than joy—it’s hard not to reorganize every Barnes and Noble SFF section when I wander in there, to put series in order, or see how little room there is to face-out covers. The reward really is the process. When a project just goes right, and editorial and the author and the artist are all happy with the end product (and maybe it even sells!) then that’s what keeps me going.

MS: When the communication is running smoothly, artists are happy with their work and with requested revisions, and my bosses are loving what they see, it’s Miller time in the Scheff household (those who know me know that it’s bourbon time, but you get my meaning). Nothing makes me happier than a team who gets excited and stays excited over the course of a project. My job is to make that happen. When it doesn’t, I do my best to figure out how to make it happen better next time. That learning process keeps me ticking, and when it goes well, my tank is full. Again, I’m lucky, I get to make art and hire great artists. I remember explaining this to my wife, or maybe she explained it to me. I love doing both because the people side, the collaboration, the creating of things greater than the sum of their parts, I just love it.

So I hope that little quiz was fun, and a little eye-opening for people. I hope you feel like you know a bit more about things from the AD POV. I know the Corporate > AD > Artist workflow isn’t always perfect. Artists have real and understandable problems with many things the corporate world does, and corporate doesn’t understand how artists think, or their priorities. In the middle are the ADs, who above all want the process to run smoothly. We are an artist’s ally, their men and women on the inside, with the conduit to affecting change at the corporate level. So include us in your attempt to make changes. Ask us questions. Don’t assume you understand what’s going on behind the curtain, and instead try to give people the benefit of the doubt, at least long enough to to have a conversation so we can create a better community for all artists.

In summation. Be excellent to each other. And that is the best way to make positive change.

Thanks so much for posting this guys. I've also been troubled by the amount of vitriol entering the public discussion. It's nice to see commentary coming from the publishing side of things.

I don't know how possible for all companies to be transparent about their policies, but having some insight into Orbit and Treehouse seems like a pretty good start.

Keep it up 🙂 I hope this sets a good example for other bloggers.

Thank you for so clearly laying out the issues we ADs deal with on a daily basis. As you said, the daily tug of war that goes on internally while moderating between corporate and artists is a wearing process that is only eased by the love of the profession. Watching PACT develop has been extremely exciting for me. Though, like you, I also hold my breath each time things take a turn for the dark and bitter in articles or the FB comment sections. As a former contract artist, I do understand where the bitterness comes from. An AD has a salary and knows there will be work tomorrow. Many artists face the constant struggle of making enough to cover rent each month. Each day holds the worry of where the next paycheck will come from. It is important for transparency sake that we tell our artists (and hopeful future artists) that we absolutely want to work with them, but someone else is not letting us. However I know how it feels to be on the receiving end of that news. It is often heard as “There is no work for you here now, and we don't have any idea when we'll be able to use you.” When you get turned down for a gig you feel qualified for (and end up needing to take on twice as much work elsewhere to cover even half of what the potential job would have paid) your outlook can spiral. The only thing that will keep this bitterness from further dividing corporate employers and artists is communication and it's great to see this message expressed here.

I think we've just found the title and focus of one of the Art Director panels for Spectrum Fantastic Art Live 3 in May! (Another great post, Lauren, and welcome Marc!)

I think a lot of the communication issues come from the fact that many artists have not worked for a company, and just don't know what's involved. And their only point of contact is the Art Director/designer.

I worked for McGraw Hill for years, in Chicago and New York, as a production artist. The Chicago office as horrible, the New York amazing. Night and Day. But they had the same process in place, because while we were different sister companies under the same McGraw Hill umbrella of companies, we still had to use the same Corporate Policy and Procedures.

So, Editorial would write the proposal/budget/sales projects for a project, and do the song and dance, the Publisher would take that and do the song and dance for the financial executives at HQ, who would then go and ask the banks for money. Once all that fell into place, (easily a 1-3 year process), the project could actually be made.

If editorial did a bad job budgeting, it was too late. We in Design and Production would get the specs and see we had to commission new art that was rather complex for $100. We'd mention this, and there was no way Editorial was going to go back and ask for more money. It would mean starting the whole approval process over. Chances are, that editor would be fired for wasting so much time.

Sorry, editorial just isn't going to stick their neck out like that. Hardly anyone is. So the problem falls in someone else's lap to deal with. While it's all fun to hear the juicy gossip of other people's fuck ups, I doubt that any AD is going to tell you of internal problems.

I know you are thinking, why doesn't Editorial ask Art what they should budget for. In the case of the Chicago office, the reasons were many and complex and often personal. And I've found in many of the publishing companies I worked for, this to be the extreme exception. The New York office I worked in was amazing and worked smoothly and did a great job.

But having worked for both extremes, I've gotten a good insight into the whole process and how things work. In none of the case, have ever the words “Now we will finally show those artists who's in charge!” ever said. I've never heard anyone say, “Fuck the artists, they take what scraps we give them!”.

Publishing is a complex machine that requires a lot of different people with different skills and thoughts and focuses. And every single department has investment in every single project succeeding. Marketing wants success as much as Editorial, Art, Design, Productions, Manufacturing, Accounting, and so on. That's a lot of different people having a say in a project.

Epic!

Great post Lauren and Marc! Very insightful.

Fantastic, comprehensive article. However, I kept reading and reading, wondering when it would get to the sex part that the title suggests? Ha!

Awesome post guys. Thanks for sharing the publishing and corporate side of things in such depth! And I think Tim hit the nail on the head with his comment above about a artists having not worked within a corporate setting. I know at least for me this is true. It's easy (and common) to get frustrated, but Lauren you were spot on when you said that empathy is key. I've found in my life that empathy really is the key to EVERYTHING. Anyway, enough of my rambling. But thanks for taking the time to spread a little more optimism in our community guys!

I think you'll find companies are generally happy to be transparent about their policies, people just don't ask, they assume they know what's going on.

And I understand, we all need to vent and bitch, that's fine, but it doesn't ever need to get personal and nasty, and it's also not how you make change.

As always, thanks for your great and insightful post!

One point is troubling me, though — you're suggesting if enough artists turn down low fees, it will help AD's push for better rates. The problem is, at least in my experience, that for every artist who turns down a low paying job, there are 10 (or 100) other artists out there who will accept the same job or even work for less. Competition is tough when there are countless artists with financial support from parents or partners, or simply residing in a different country with low costs of living.

thanks adam! most ADs have been artists themselves at some point and the more people in this discussion that know both sides f the fence the better!

I'm happy to help! And I'm so in. Is it too early to book my flights to Spectrum? I wouldn't miss it!

agreed, the amount of moving parts in any big company is insane, and daunting.

hmmmm. good point. ehrm. we'll save that for the Spectrum panel then!

I'm not black & white suggesting artists turn down low fees. It's a complicated issue. Companies with lower fees attract artists who are younger in their career, and they get not only the fee, but the first step onto the ladder. Once you as an artist are ready to take the next step on the ladder, then you turn down the low-paying jobs and move up. This is an amazingly hard thing to do, and it's very scary to turn down any work. But I do know that it's when artists take jobs they feel are beneath them that the most bitterness is sowed.

Some companies will never be able to raise prices, they operate too close to the red, and they are forced to keep taking the greenest artists. Some companies will realize they can squeeze a little more money out of their budgets and raise prices. It's a very delicate balance and a risky one, but communication with your AD is only ever going to help.

That's something to consider hena. I think it's like Lauren says, it's the first step on the ladder. Once you take that step, you should consider moving on up.

If the amount offered is too low for your work, don't take it. If it takes you say 10 hours to do the work, and the money isn't enough, rather than suffer, take that ten hours and reinvest it in yourself, either doing a personal piece or trying to find new clients with bigger budgets.

I did weekly illustrations for a local magazine for almost two years. The pay sucked, but I used it to push myself, in terms of tight deadlines, working outside my comfort zone, figuring out what I want my art to be and so on. When I felt I had gotten about as much as I could doing that, i asked for more money. When they said they couldn't afford it, I moved on.

I replaced that income, which had little bearing on my ability to meet my cost of living, with better paying clients. The time I normally spent drawing for them, I spent making contacts with other companies and self promotion.

There has always been people willing to work cheaper than you, and there always will be.

That makes sense. Thanks for your replies!

It's never too early. 🙂 We've got some other art director-centric ideas cooking that we'll run by you and Irene soon (and maybe there should be WINE at the AD meet and greet in '14). But “Sex, Lies, & Art Direction” is a definite!

Thanks Arnie, I'd love to join in the fray!

Yep, I think Tim and Lauren nailed this one. New artists willing to take low pay will always be out there, so best to figure out a way up the ladder.

The artists who have helped me by turning down work were artists we REALLY wanted, big award-winners with enough cache that it got the attention of those higher up. So when you go win your awards, help the AD out by saying no to low pay, bad contracts, and tell them why you're saying no.

Thank you, once again, for all the hard work you put into your posts to create more dialogue in this community. I'm an artist, currently working hard on the technical aspects of my portfolio (I'm getting there, slowly but surely!) But thanks to ADs like you and blogs like Muddy Colors, I will be armed with a well rounded knowledge of the industry and it's relationships when I'm ready to approach ADs.

I wonder how many artists have lost it all because “I really want to work with you” doesn't pay the bills.

And most importantly, I wonder if Corporate/Editorial care.

I'm totally attending that panel. (Great article – as always! – Lauren and Marc).

Well, I can do the sex and lie thing.

in emails so we can annoy our bosses with them! lol

No, “I really want to work with you” absolutely doesn't pay the bills, and I'm not expecting anyone to hang on the line waiting. Like I said, I wish I could support every talented artist with commissions…

It's not that corporate/editorial don't care, it's that they are not talking to artists everyday, and they don't think about it. The same way that artists often don't think about the editor that's heartbroken that they have to drop an author who didn't sell enough copies of books. There's a middle ground somewhere. An industry can't survive on starving people, I am right there with artists on that. But an industry also has to make money to stay afloat. There's a middle ground somewhere, I'm confident that collaboration and communication is the way to find it.

Thank you for the article, it was a great read. I do wonder though, as an illustrator – how would I go about convincing art directors that I am not only good with the art but also the art of communication? I mean, I don't consider myself a prima donna, but short of working with me, you'd never know for sure. Especially for artists with representation like myself, it is difficult to establish contact with art directors personally as our agents would prefer to handle the business and marketing side as much as possible.

P.S Sorry for the deleted comment, I did not check off the 'Notify Me' box and could not edit the comment afterwards.

Marc–We'll count of seeing you!

Bill–We know. 🙂

Your art speaks for itself, but your communication is what proves to us you are ready to handle business. ADs survive by having a sixth sense about who is going to be good to work with and who's going to need coddling, or spoon-feeding, or ego-fluffing. You'd be shocked how much about you comes through from your emails, short portfolio reviews, what you say about yourself on your website, the level of care you take in communications, etc. If you want to stress your business head and eagerness to work, then do so in your cold emails, or stress it when you meet an AD. Do a minimal amount of research and note something personal to the company you're emailing — hey i saw this cover and I think my work would fit right in with what you did there, etc.

Hi Charlene,

I wrote two articles over at Agency Access about this topic, how to stand out with personal emails and how to network in person. Enjoy!

http://lab.agencyaccess.com/blog/bid/55465/Standing-Out-With-Personal-Emails

http://lab.agencyaccess.com/blog/bid/58059/Networking-at-Events-Be-Good-Nice-and-Awesome

This begs for a book a la Barbara Gordon's out-of-print, How to Survive in the Freelance Jungle.

These posts are very informative.

Thanks Lauren, Mark, for your replies!

It is good advice for illustrators who can contact you directly. I'm with an agent and she prefers to handle all aspects of marketing; not sure how it is for all other illustrators with reps, but it can be difficult to reach out with such restrictions.

You're right, Charlene. However, even with an agent (and yours MAY be different) it is perfectly acceptable to do some of your own footwork making the friendships and connections you need, then funneling them to the agent when a commission comes up.

Awer artiste is a skilful artist who has plenty of experience only at that field and does all his duties very sincerely.He draws hypnotic creatures and oniric monsters with the try to distract individuals from the boredom of everyday activity,giving life to artistic remedies and methods to excape from human troubles.

wow ..it has nice features..thanks for sharing with us..:)

Visit Sports man outfitters for all your outdoor activity needs.

Our store is committed towards providing you with the best options for your passion of outdoor activities.