|

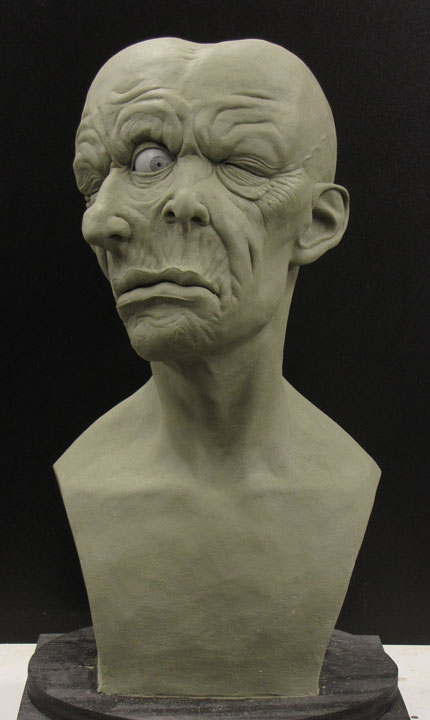

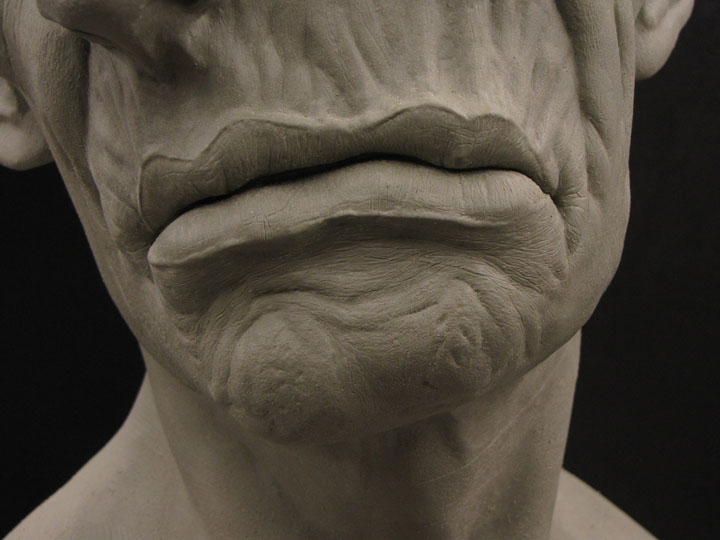

| “Side-by-Cyclops”, by Alfred Paredes. Life-size, Chavant NSP medium. |

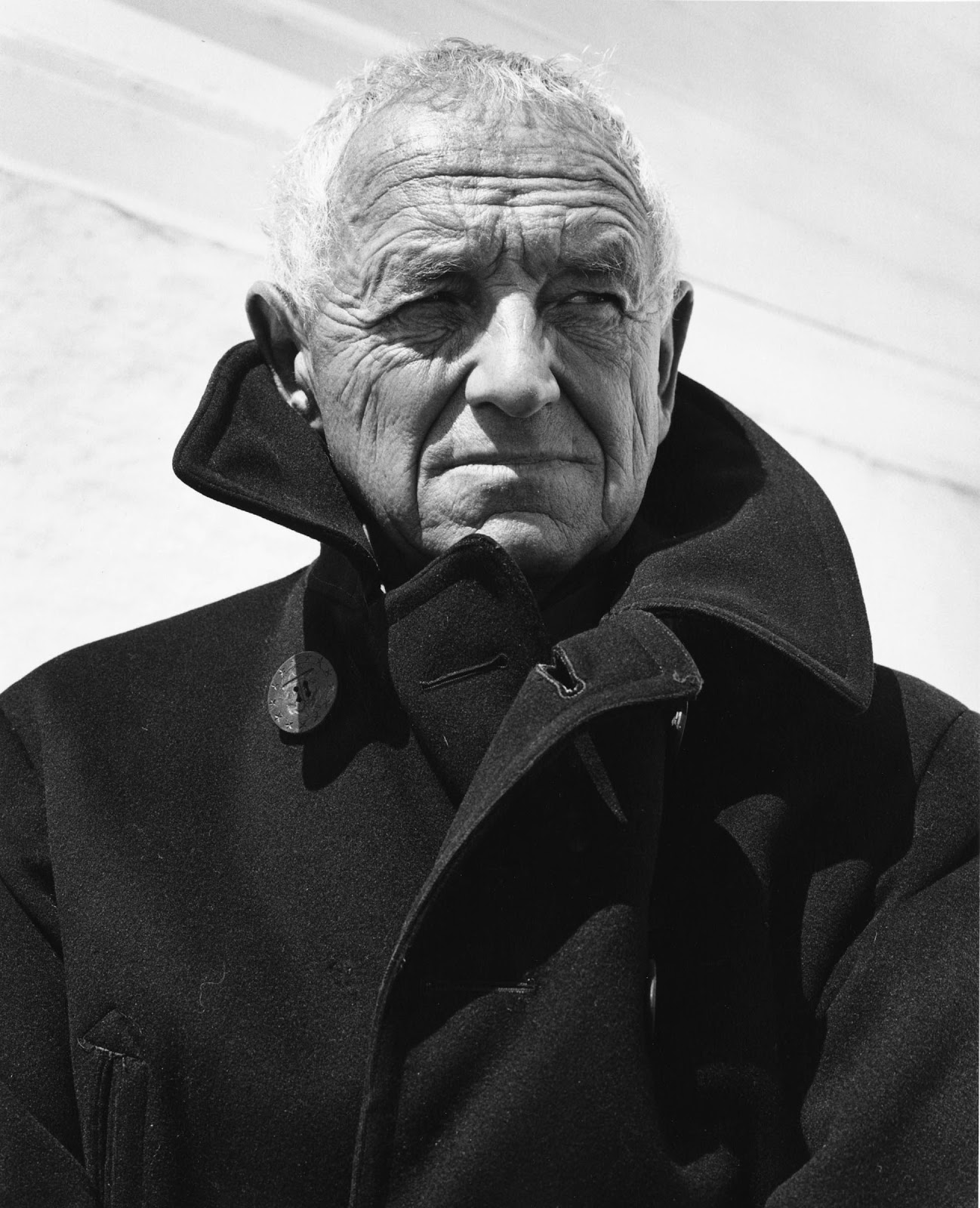

Alfred Paredes and I have been online friends for some time. Through our correspondence I’ve come to know him as an honest, caring and humble man with an open and generous nature. His classical training really brings depth and conviction to everything he does. He’s an artist of great versatility and skill. The guy has chops!

This piece started as a conversation with a friend. I was filling her in on a time when I had a blindingly brilliant moment of genius. I’ve always had a fascination with Cyclopes While I was doing some concept sketches, I came up with a creature with three eyes. A Tricolps! I was on to something now, I thought to myself. A Cyclops, a triclops and… Ooooo! What about a Biclops? That brilliant moment of genius faded when I realized that we’re all biclops. My friend and I had a good long laugh. But from all that, came an idea of two merging faces, forming a Cyclops. And so, Side-by-Cyclops was born.

The money shot of this piece puts you in the eye-line of the Cyclops. I wanted him looking creepily down toward the viewer. This slightly off center view also gives you a true sense of this guy’s character. You can see that he has quite a few wrinkles and sags, suggesting that he’s an older fellow. It also makes the viewer curious about seeing what the other “face” looks like.

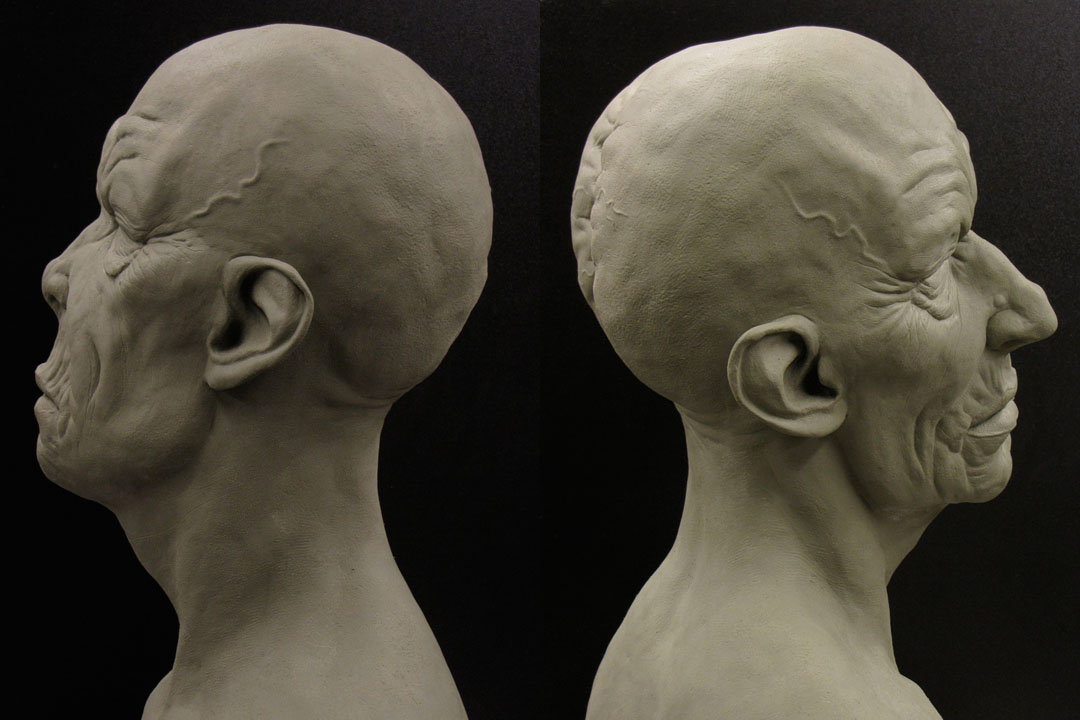

As I started this sculpture, I wanted to make it clear that the two faces were distinctly unique. I wanted them to be able to be seen on their own, when viewed in profile. This meant moving around the piece constantly while I was blocking it in to make sure that my concept was working. An odd thing that happened as I worked on the front of the faces. Because they were merging, my brain had a hard time separating the two sides. I kept having to cover one side of the head with one hand, while I sculpted on the other side with the opposite hand.

The side of the head also gave me a place to provide the viewer with an area of rest. The face is really busy and there’s a lot to see. If the whole head was as detailed and texture heavy as the front, the viewer wouldn’t really know where to focus. As their eye moves past the faces, the sides of the heads allow for the viewer a visual respite.

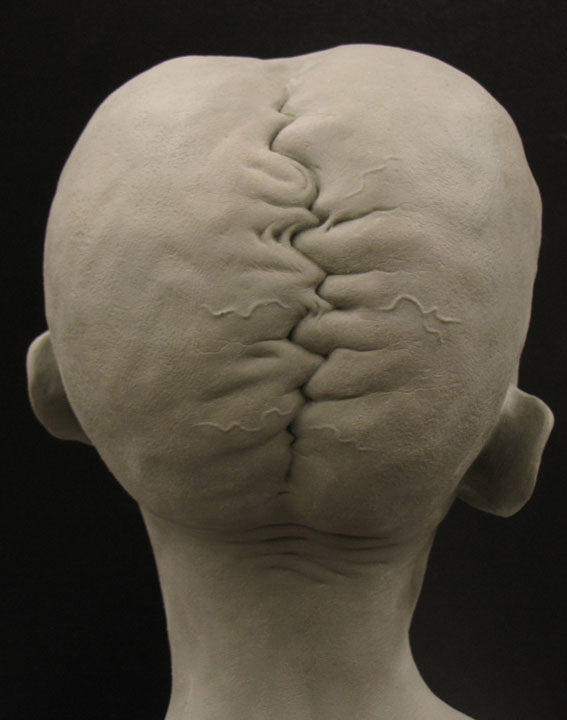

Once around to the back, I wanted to hold the viewers attention for just a little while longer, before they went back around to the faces. The back of the head lets me tell a little bit more about this character’s story. The forms moving in and out of each other suggest both a coming together and a pulling apart.

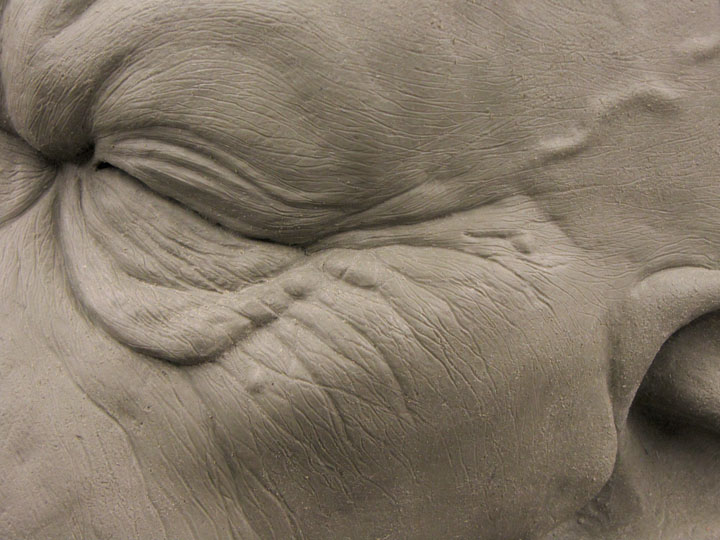

“The devil is in the details”. I’m not really sure that I fully understand what it means. I think it means that the difficulties and challenges of a project lie in its details and how they inform the piece. Paying attention to these areas is important. Skin blemishes are natural to almost all of us with our tiny bumps and moles. Finding places for these types of details is important to make your piece look like a real character.

Mouths are a place that I feel tend to be overlooked in many sculptures. Back when I was in school and learning how to sculpt a face, my professor pointed out a technique that goes back centuries. He told me a story about stone carvers working on their pieces. They would finish their sculptures by carving a small gap in between the lips and then stand back and watch the marble take a breath. I don’t know if any of that’s true, but it’s certainly a nice romantic vision of sculptors. I don’t exactly stand back and watch my piece breathe. Nor do I wait until the very end to add that little gap. But I do add that gap in almost all my pieces. That sense that piece might take a breath is something that is hard to convey. I know that without that little touch, the illusion is often not as convincing.

“The eye’s have it!!” In this case, it’s just the one eye. Normally, when I sculpt a face I like to sculpt in the iris and pupil. I think it goes back to my days of doing fine art. Leaving the eye as a round ball is something that is more common in commercial sculpture. I intended for this piece to be cast in resin and painted up to look real, so I left the eyeball smooth. I still needed to have some sense of where this guy was looking while I was working on him, so I drew in a pupil and iris. I played around with where he would be looking. You’d be surprised by how much the mood of a piece can change by simply moving the eye around. He went from looking scared, to looking confused, sleepy to indifferent. Finally I landed on the perfect spot and the right mood for the piece jumped out at me.

The character’s story is something that each viewer fills in based on their own personal experiences. We each bring a lifetime of stories, images, faces and emotions to a piece that builds a unique interpretation of each work of art we see. I had my own story while working on this guy, I hoped that each viewer would bring their own interpretation and connect with him in a personal way.

Beautiful piece, thanks so much for posting.

Fantastic art.

http://www.speedwayautoloan.com