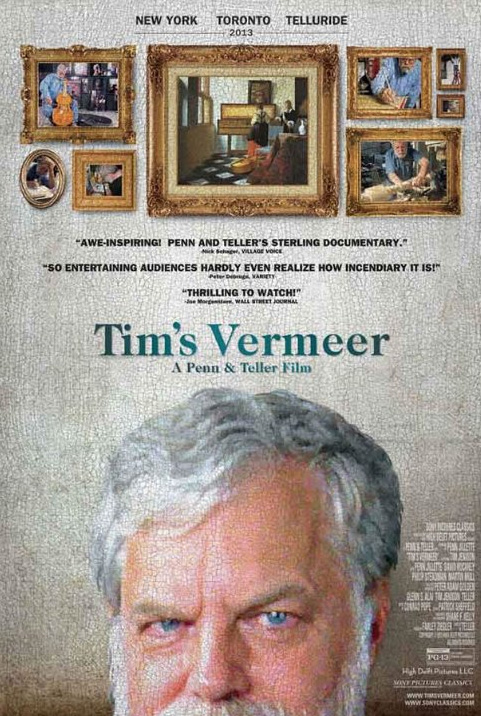

Welcome to Les Couleurs Boueuses Cinéma. In this installment, I am going to review Tim’s Vermeer.

Tim’s Vermeer stars inventor Tim Jenison who you may not have heard of, but I bet some of you have used Lightwave 3D or Video Toaster. Tim founded Newtek earning him the money and time to invent lots of crazy things and invest time in whatever obsession he might have. Penn Jillette, the famous magician and long time friend of Tim, is also featured in the film and was a producer, along with his ever taciturn partner Teller.

I think that rather than having you read all the way through this review to see what I thought about it, I will just tell you right now. I loved it. I highly recommend it. Don’t take that to mean that I agree with everything expressed in the film. You have to read the review to find that out!

The gist of the movie is that Tim became interested in the idea that Vermeer used an optical device to assist him in painting and set out to try and recreate not just a Vermeer, but the room he painted in: the floor, the furniture, the costumes, the light… everything. And to prove that Vermeer did indeed use an optical device to help him paint.

He was intrigued after reading David Hockney’s book Secret Knowledge, given to him by his daughter. In that book, which was surrounded by some controversy when it was released, Hockney argues that when art took off from the flat, stylized forms of the middle ages to the highly realistic and accurate renderings of the last few centuries, it was because of optical aids, like the camera obscura. The problem with the camera obscura as Hockney described it, is that it could really only be used for drawing, tracing the projected image. You can’t paint under a projection because the light being projected affects the color and value of the paint being applied. It is only accurate over a white surface.

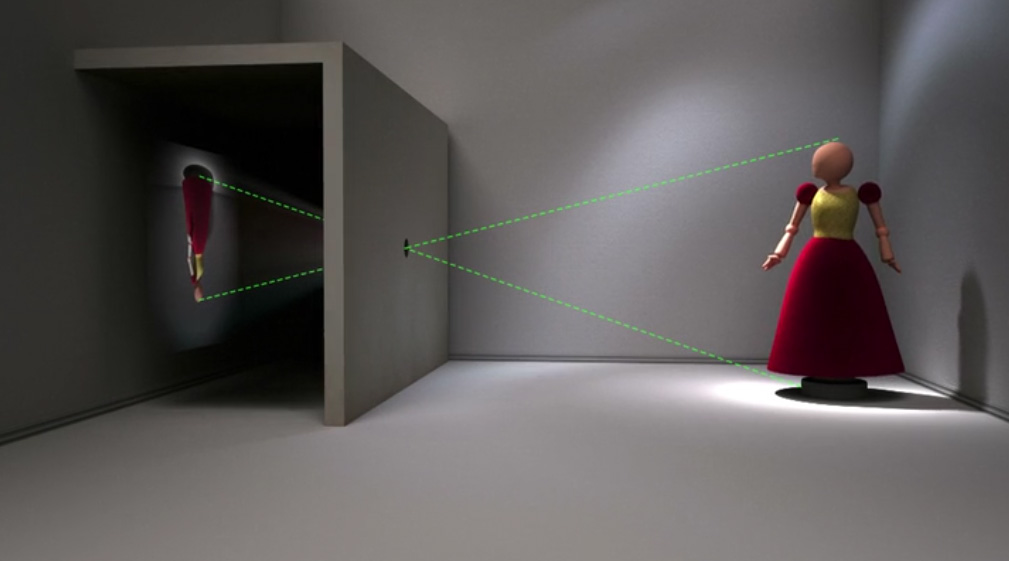

|

| Camera Obscura schematic |

When Tim looked at a Vermeer, in his words, he felt that it looked like it “came out of a video camera.” Tim’s first idea was to set a small mirror at 45 degrees and set the subject in front of you (or a projection if his thoughts on Vermeer are correct). You can see your painting and the subject at the same time by shifting your head back and forth over the top of the mirror and your painting.

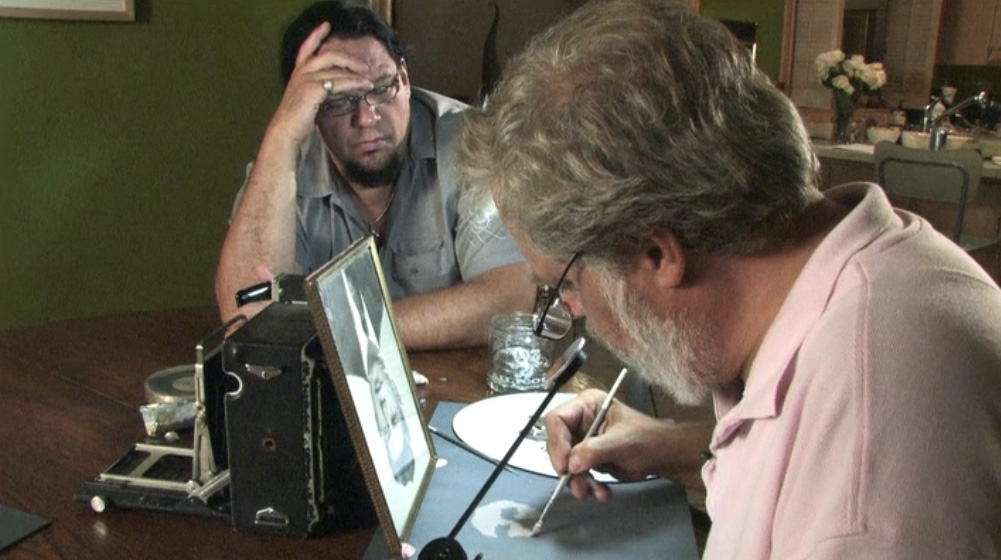

|

| Tim doing his first oil painting using the mirror device |

Tim had never painted before, but finished a nice little oil copy of a black and white photograph in a few hours using this tool. He would mix the paint until the edge of the mirror, reflecting the subject, disappeared against the paint, meaning it matched values.

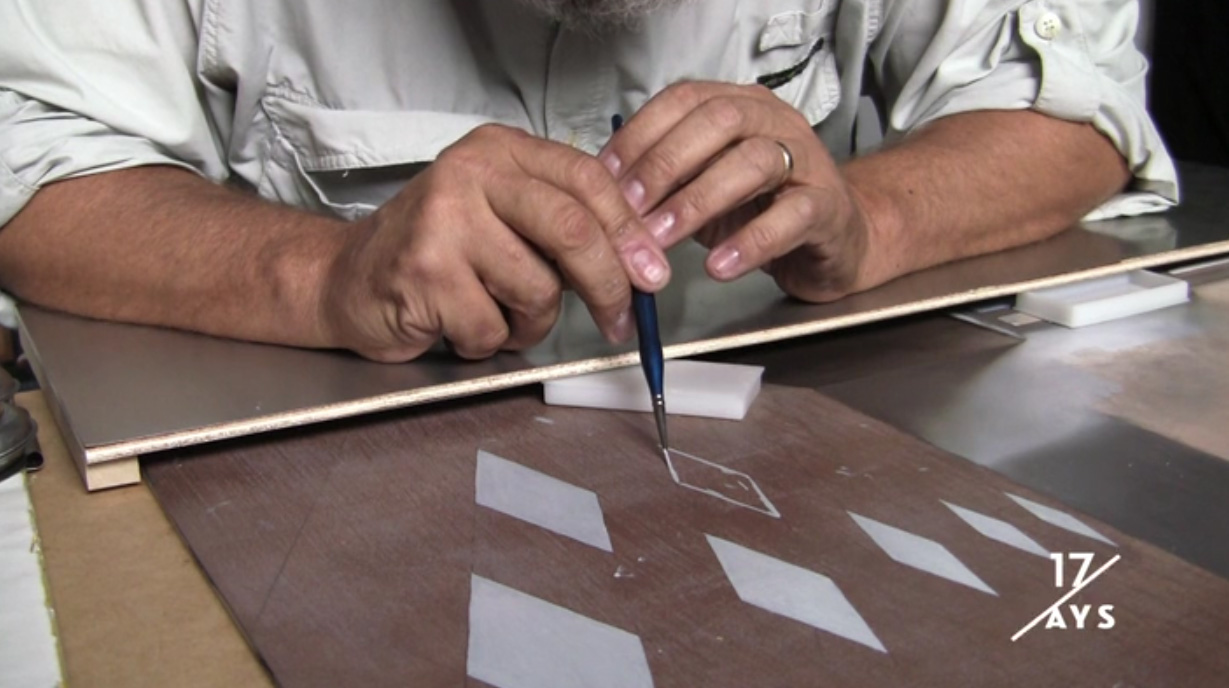

|

| You can see the reflected image of the photo over the painting in the mirror device |

His initial theory was that Vermeer used a small camera obscura that projected the image onto a piece of ground glass that could be seen in daylight instead of inside a dark room. He could then place the small mirror device to aid the painting process in front of the glass plate on the back of the camera obscura. This would allow him to not just draw, as with Hockney’s setup, but paint and match colors and values.

|

| Polishing a lens |

Once he decided he knew how Vermeer went about it, he set out to learn how to grind glass to make the lenses the quality appropriate to Vermeer’s time (modern lenses are too good and would corrupt the experiment), grind pigments to make paint, recreate the vase, light, musical instruments, dresses and all the elements needed to reproduce Vermeer’s studio.

|

| Tim learning to grind pigments into linseed oil |

He travelled to Delft, studied various Vermeers and then returned home and rented out a warehouse in San Antonio where he could create the north light studio of Vermeer.

He consulted a man named Philip Steadman, who wrote a book called Vermeer’s Camera. For me, it offers the most compelling evidence so far that he used an optical device, though I say that not having read the book, but just heard the synopsis offered in the movie. Steadman takes 6 of Vermeer’s paintings and uses them to create a map of his studio. Using geometry, he identifies where in the room the camera obscura would have to have been for each painting in relation to the back wall of Vermeer’s studio where the camera obscura may have been projecting to. The geometry apparently lines up exactly in all six paintings. Interesting.

Tim decided to try and reproduce Vermeer’s The Music Lesson. He doesn’t copy the original, but uses it to recreate the room and all of the elements in it to paint. He felt that it would be a good subject to start with because there were many elements in it that could be recreated objectively. Using lathes and CNC routers and a whole incredible shop full of wonderful tools he starts making the elements of the room.

Tim has a strong obsessive streak that I have to admit I admire and as artists, we can all probably relate to a little. I love his determination and inquisitiveness. Whether or not you agree with the conclusions of the film, I found myself caught up in his efforts and his “whatever it takes” attitude to assuage his curiosities.

|

| Tim visiting David Hockney’s studio |

Tim decides to travel to England to consult Hockney and show him his discovery of the small mirror device. Hockney is very pleased, I am sure seeing it as additional validation of his theory that all the great artists used optical aids. Hockney offers a quote that I thought was good.

“The idea that the Italians didn’t use this (the device) because it would have been cheating… is childish.”

I agree with the idea that using a tool, or whatever, as some kind of a ‘cheat’ is stilly, but I do not agree with Hockney. He has to contrive that no artist revealed or recorded his working methods, which is why we don’t have a record of any of the artists he identifies having made widespread use of a camera obscura or optical aid. Unlikely. It also discounts fully documented efforts by artists in the 19th and 20th century drawing from life and producing the kind of work Hockney insists comes only with drawing aids.

When Tim returned back to San Antonio, he was ready to get started, but quickly ran into a problem. The image being projected was too fuzzy and dim for him to be able to capture all the detail. He tried many different setups, but eventual came upon the idea of projecting the image onto a concave mirror rather than a flat surface, which collects more light, creating a brighter, clearer image. This allowed Tim to project an image in a brightly lit room. Bright enough for him to use the mirror device to start copying.

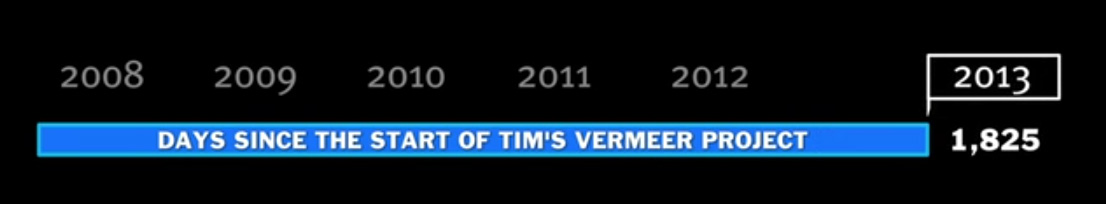

|

| You can see the day ticker in the bottom right corner |

Time to start painting. He went about the painting in a very mechanical, practical, almost robotic nature. After a few weeks of painting, he stated, “Wow, I am not trying to make this look like a Vermeer, but it really looks like a Vermeer.” I can’t agree though. It does look like it in the sense that he recreated so many of the elements that you see in a Vermeer. However, the paint doesn’t have any kind of elegance, or interaction with the brushwork that Vermeer’s work does.

Part of that comes from the very slow progress of the painting, but also in the way that Tim paints. He paints with very small brushes, dabbing the color in, until it matches what he is seeing through the lens and mirror. Rather than smooth passages of paint accented with the punctuated light and strokes you find in a Vermeer, this painting is more pointillistic. It is a series of discrete elements that gives a sense of the original, but ultimately falls short of the beautiful surfaces of the original.

At this point, he has a little mishap, wherein the lens gets bumped and the chair he is working on is off perspective without him realizing it.

|

| The chair that was off due to a bumped lens |

He states that when he looks at the chair, he has a “sense of revulsion” upon seeing it. I thought this was interesting because I have often expressed to my wife, that when something is off in my work, it makes me feel a little sick until I fix it. Is this a common reaction for you? Let me know in the comments.

|

| The detailed painting of the wool rug |

Tim’s attention to detail is impressive, from the beautifully intricate inlay on the virginal, or the merciless and never ending weave of the rug in the foreground. He works on the rug for weeks on end. Tenacious and meticulous, seeing Tim progress is very compelling viewing to me. I don’t know what that says about me…

130 days after starting just the painting itself (the whole effort took 5 years!) he was finished and ready to varnish.

Penn Jillette closes the film stating that, “my friend Tim painted a Vermeer, in a warehouse… in San Antonio… he painted a Vermeer.” It is a good line, but it isn’t true. It would be like saying you could break down a Mozart into all it’s components and generate some objective means to churn out a “Mozart.” Tim acknowledges that he is standing on Vermeer’s shoulders and the merits of his piece are owed to Vermeer. To Tim’s credit, he states that this doesn’t prove that Vermeer used these tools, but he is 99% convinced.

As I said before, Tim’s painting doesn’t have the elegance of the original. It feels mechanical and lacks the exquisite execution you would see in a Vermeer.

|

| Tim standing in front of his “Vermeer” |

I have read a few other reviews of this film, and they are fairly loud in their critique of the idea that one could “paint a Vermeer” as if it is a series of objective steps. I share that, but am not dismissive of the whole and I also see a lot of wonderful aspects to this effort. I think that there are some real possibilities to the conclusions that Tim makes. I also think that if he is right, rather than diminish Vermeer, it shows how masterful he was, especially when comparing the two painting side by side. Tim’s Vermeer is on the left. Click the images to enlarge.

Well done Tim. You didn’t paint a Vermeer, but you did open up some new possibilities and insights as to how the real Vermeer may have approached his work. Along the way you made a fascinating film with great passion, persistence and hard work. Who wants to do this with Alma-Tadema’s Spring?

Howard Lyon

Instagram

Twitter

Website

All images in this post copyright © 2013 – Sony Pictures Classics, except for the image of the actual Vermeer painting.

My favourite part is when Tim notices the slight curve in the harpsichord's ornament, indicating the use of a concave mirror. (or was it distortion by the lense? Can't remember)

I can't help but be convinced by the film. Yes, there's a vast difference in the brushwork, but in my mind that can be attributed to the fact Tim never painted before. What a painter comfortable with their brush technique could do with such technology…

I really don't understand the obsession with this, is it to discredit his work? There are plenty of artists who can draw and paint highly realistic images without optical aids, and many that can't. We all have different aptitudes, could it just be he was ahead of his time in terms of skill? Frankly, it just seems easier and more fun to learn to draw and paint through observation, it can be done.

I haven't seen the movie but there was something I read about this film recently and it really stuck with me. The insistence that you can only get the nuance of the color of the wall with an optical aid. That to the eye it's just flat white. In school we were told to not use a camera because it flattens things out (the opposite of what he said), also we spent a good bit of class time discussing and putting into practice seeing the nuance and colors in white. To say that being able to recreate the nuance of the wall is impossible without a tool really turned me off.

Very interesting. I like the Mozart analogy.

Jameson Gardner

I think that it is valuable to know how any artist worked (if this is indeed correct for Vermeer), don't you? If this is right, or close to it, I don't think it discredits or diminishes his work at all (unless you think that using a particular tool or procedure is a cheat). I think it is fascinating too. If someone was interested in painting like Vermeer, or a student of art history, this would be very relevant.

You are right though, many artists draw with high accuracy and skill without any aids, and that is why I don't agree with Hockney's assertions. I agree that part of the joy of painting comes from the challenge of it and improving.

Thanks for giving the post a read and commenting!

Jessica – I completely agree. I thought that line was silly. That or I missed the point he was trying to make. I thought, well if you can't see it with your eye when observing it directly, how would it help to use your eye to see it when looking at the projection of the camera obscura. In both cases it gets filtered through your naked eye… weird, that didn't make sense.

As far as a camera flattening the image, that is true, especially when the subject is closer since we see with two eyes set apart and you get some parallaxing of the image. With a camera, you get one 'eye'. As the subject gets further away from you though, this doesn't matter as much.

Even with that error, I still found the film as a whole to be really fascinating. I would recommend it. Not as some solution to a way of painting, but as a potential piece of art history and technology… even if they say some silly or inaccurate things along the way. 🙂

Thanks for giving the article a read!

Thanks Jan for giving it a read! I would like to give it a try. 🙂

Loved the film and found it very intriguing. However, calling this his first painting, without referencing the lap over skills that he has spent a lifetime developing, was a little disingenuous . In particular, I was amazed at how steady his hands were.

Great article as always, Howard! I found it interesting that Tim spent five years and almost 2000 hours learning how to create one painting with an optical device. If he would have spent that time learning how to draw and paint, he would've been able to create many paintings and have the skills to do so without any tools or crutches. Still, he learned how to see, which is the first step towards becoming a realist. It just took him a long time to get there.

“…the kind of work Hockney insists comes only with drawing aids.” I've read Hockney comments where he stated specifically that he was not attributing the use of a device to all artists in the development of naturalistic realism in the history of painting. I haven't seen this video, but he has been at pains in the past to make listeners understand that he was not declaring all painters used such a tool, only certain influential ones.

Something often missed in the discussion is obvious, but worthy of note. It would only take one or two significant painters of the time to produce works using the proposed technique and it would naturally and necessarily spur imitation. Not necessarily duplication. Consider in early artistic development that most children typically draw the sky as a roof and grass as a floor. A band of blue and green at the top and bottom of their pictures. As they develop, the first thing that occurs (typically) is that blue is depleted from the crayon kit as they start using it to bring the sky all the way to the ground. Later, the ground stops being a flat band. They add hills. They add distance. Now they add rudimentary attempts at perspective. By observing, practicing, and developing, they grow not simply in skill but in observational execution.

The same occurs with artists exposed to new methods, materials, and influences. Imagine the thrill you each likely experienced on discovering an artist's work that was wholly new and different to you. The sense of wonder, the moment of appreciation that becomes an epiphany that becomes in turn a catalysts to adopt new insights and approaches. I can clearly and vividly remember those moments as a kid. Snapshots of discovery that informed my vision of what art could be.

I don't for a moment believe that all of the artists we consider the great Masters utilized optical devices. But they did not live in a vacuum. Any given number of contemporaries — be they aspirants or colleagues — standing before a paradigm setting work created with such a device would be inspired to see differently, to emulate, to change, and to master the realism they saw in the work before them. “Art History” is full of such leaps.

Great response Thomas! I will have to do more reading to clarify what Hockney has said since the initial release of his book. The articles that I read interviewing him listed out so many artists of note, and the examples he used in his book were pretty far reaching, that it seemed he was painting nearly all history with the same brush. He also does contend that we don't have any record of the use of such devices because of the secretive nature of all the artists that may have used such devices. I don't buy that though. There are too many journals and student notes that have survived. That doesn't mean it didn't happen, but seems unlikely that it was widespread. As you said though, one or two artists could have set a new paradigm. Whether or not it happened several different times through history without record of it… which Hockney does suggest by virtue of the artists he says evidence use of a camera obscura or camera lucida… I dunno. I hope we find out for certain at some point. I find it very compelling history.

Nicely done, Howard.

Howard thanks for the article. Now I am compelled to watch the movie. But I must say whilst I'm fascinated to see what Tim's process was I don't feel any need to know if he was correct or not. Vermeer's paintings are great either way. Its not just about execution its about composition, expression, subject, feeling etc etc. An artists job is not just to capture exactly what he see's but to convey his “way of seeing” or telling. Even a photographer has a “way” he see's the world. If Vermeer “cheated” he still did an awesome job of conveying some pretty strong feelings.

I also now need to dig in to what Hockney is saying too! I find what's being implied here a little of a “blanket” sensationalism. I have seen as most of us have, many artists young and old create very realistic works from scratch without the need of optical aids. And I just don't cannot picture some of the great's out in the fields painting masterful landscapes with aid of a small mirror, it would just be too cumbersome and awkward let alone the exposure to passers by.

Drawing on impressionism here, which is not the best example I guess but its late :), but Monet painted some fantastically realistic, at least from a color standpoint, images, from painstakingly observing the same scene over and over at different times of day. I think if he had been using a camera obscura folks would have seen it 🙂 and his highly competitive fellow artists would have called him out.

Either way I now need to go watch this movie and read Hockney's comments:

Thanks Howard for you insight and continuing to be a mentor and inspiration.

Peter

They have an interview with an “eye scientist” (can't remember the actual title) who (correctly) explains that the human eye and the way our brain interprets signals sent by the eye are limited. It's not that we can't see the light gradient on the wall, we can. But it's (according to the scientist) impossible for a human to interpret what we're seeing accurately and transfer that to the painted image.

And you've likely noticed this yourself (and James Gurney has written several blog posts about this) – paintings from life differ significantly to photographs taken at the same time. Sometimes these differences come from slight distortions of the camera's optical system, but when it comes to colour and value, our brain is much more likely to misinterpret things and come up with interesting shifts and changes.

(there are many examples of such optical illusions, but one especially comes to mind – remember the classical proof we understand value through its relationship with neighbouring values? http://listoffive.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/5-Amazing-Optical-Illusions-004.jpg)

Tim's tool neatly sidesteps all the misunderstandings our eyes and brains might throw at us and lets the artist compare the value/colour they're putting down to the actual value/colour directly.

Yes, you can paint a gradient of light on a wall, you might even get quite close. But (according the scientist, whom I have no reason to not believe) it's impossible to get it this accurately without a similar tool.

I can't help but wonder why people who can't draw or paint realistically are the one who try to figure out the “tricks” of the old masters. And why the insistence of the camera obscura? The camera obscura effect was known in ancient Rome. Why didn't they use it? Why wasn't it used until after perspective was figured out in the Renaissance? And how did these artists create self-portraits, or sculptures, or murals/frescoes? How did they paint on a vase???? Or use transparent glazes???

I didn't see the movie, but this doesn't make any sense to me. If he was trying to prove that it could have happened, that's one thing. But to insist that this is the way that someone from a different culture, a different time, with different abilities, with a different understanding of the world, how he worked is absurd. I wonder how well he claims to know his wife/partner? Someone he actually knows.

This just frustrates me.

Howard,

Great review and I am looking forward to seeing the film myself. I have just finished reading Hockney's book Secret Knowledge and though it is fascinating stuff, the theory is just that, a theory. I admit that he has some good arguments, but saying that the quantum shift from an artist like Giotto to the chiaroscuro and realism of a Caravaggio is solely due to mechanical devices such as the camera obscura and later the camera lucida is a bit of a stretch. Given that the documentation of such devices is sketchy at best (pun intended) I find it hard to believe that optical devices were in widespread use. Hockney does temper his assumptions with the idea that it probably wasn't even a majority of artists using these devices, but that more probably it was a few influential ones that spawned the new realism and that imitators then picked up the ball and ran with it. The fact is that it will never be proven what exact methods were actually used by someone like Vermeer. None of this dampens my interest in seeing the film though, on the contrary, after reading Hockney and your review, I want to see it even more. One thing that was of interest in the book, was a side by side comparison of a descent from the cross painting by Caravaggio and a copy of that painting done by Rubens. In the original, Caravaggio's figures are stiff, the shadows are heavy and the picture plane is flattened. All this, Hockney argues, is the result of the limited focal distance of the camera obscura and the harsh light needed to produce the image. In the Rubens copy, the skin tones and weight of the figures feel much more realistic as does the depth of the picture plane. Some of the background figures are more sensitively designed and I think the Rubens is a much stronger. He didn't use the optical devices, but rather relied on his knowledge of drawing and painting, resulting in what I felt was a much stronger piece. I think this is the ultimate failing of Tim's Vermeer. He may have made a technically accurate painting of the scene, but there seems to be very little life in it compared to the real thing. In the end, tools are simply tools. Without the knowledge and vision of a true artist, technically accurate realism falls flat.

Jan – I am late responding, but I wanted to say thank you for taking the time to respond. I don't question that the scientist is qualified and the statements that he makes are accurate. However, I don't think the input he gives and the statement that Tim made (that the eye just can't see the same way as a camera) is entirely applicable.

The tool does make it simpler to find the right mix. Our eyes and brains are very good at comparing values and colors right next to each other (this one is ligher/darker/warmer/cooler). An artist starts a painting with a value and color and starts to lay in more colors, making corrections and adjustments where needed as adjacent colors and values are put down, eventually achieving a very accurate rendition (at least some artists do). If one were trying to accurately identify an isolated swatch, or two non-adjacent swatches, we aren't very good at that, but that isn't what you do when you paint a picture from observation or life. Color is laid in or rendered in relation to the colors around it, giving a point of reference. You can make continued and updated observations and adjustments.

So, my issue with the statement (paraphrasing: that you just can't do something like this with the human eye) is that it isn't true. Many artists make very subtle and accurate observations from life, just as subtle and beautiful as Vermeer. It might take more time without the tool that Tim and possibly Vermeer used, but it is possible.

You can also use tools other than lenses/photography to match colors, like this:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9JY-AZ48wMQ&wide

This video also shows how he uses a deliberate process to aid in achieving accurate color and value: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sRewRXX7H6s&list=TL_dSIKRaKX0geFrdmc8UAMuZee5FuCD7u

You say there is no reason not to believe the scientist, but what if you saw examples that refute it. Maybe the scientist made the statement without all of the data available? I am no expert on optics and neurology, but I have seen some paintings that I believe refute the statements I took issue with. Mark Carder's work in the DrawMixPaint videos are just one example.

Thanks again for participating and taking the time to respond.

Howard

Great observation Greg! I do love the Ruben's copy you mentioned, though I love the Caravaggio too! I look forward to hearing your thoughts once you have had the chance to see the movie. Thanks!

Sorry, but all this is based on a complete misunderstanding of what was said. I just watched the movie and they don't say the eye can't catch the nuances of COLOR. It clearly says the nuances of LIGHT. It actually goes on and on about this. Not only is there scientific proof for this (NO eye can paint the amount of detail on a white wall sitting 20 feet away from it), but how about historical proof? Why is it after centuries upon centuries of painters painting that Vermeer is the first artist able to get the gradations of light PHOTOGRAPHICALLY PERFECT? Rembrandt is known for his use of light, but it's a more painterly version of light, not light as it exists in the real world. Even today, we can look at other painters masterful at working with the gradations of light – like Edward Hopper – and nobody would be able to recreate his paintings using the technique used here. Hopper had a better eye for the gradations of light than 99.9% of the painters throughout history, but his paintings are still artistic representations of what he saw. Vermeer's paintings are PHOTOREALISTIC representations of the tableaux he created in his workroom.

No, Tim Jenison didn't “paint a Vermeer”. Because he wasn't copying a Vermeer. He created a workroom tableau and a painting technique that mostly recreated Vermeer's workroom tableau and a what many believe was Vermeer's painting technique, and he painted a shockingly similar painting to the original Vermeer. The fact that it came out so close to the real thing by a guy who has never painted a full painting says that something a little more than the human eye was involved back in Vermeer's day also. Look at Vermeer's painting of Delft. He was across a river, yet those buildings show more detail than similar across-the-river paintings of his era. Are we to pretend Vermeer just had superhero vision?

I think the problem some people – mostly artists – have with this “theory” is that they believe it's a case scientific people diminishing art. But art is art. Nobody is saying this technique makes the Vermeers garbage. Yes, how we got to the final product is interesting, but the technique isn't what's hanging on the wall. Tim's Vermeer is gorgeous. The original is gorgeous. Each has aspects that are better than the other and aspects that are worse. And yet the “copy” looks remarkably like the original considering he wasn't copying a painting but a situation. That fact could simply mean that maybe Vermeer was a better photographer than painter. He had a great eye for staging and light and working with models – just like a photographer – but cameras hadn't been invented yet. But something similar certainly had been, and many Renaissance artists are now believed to have used scientific means to improve their paintings. So what? Many MANY artists now use technology in their art. That doesn't mean they aren't artists, and it doesn't mean those Renaissance artists weren't either. They're just DIFFERENT artists than we originally thought they were.

2000 hours and paint something with that fidelity and lighting acuracy…nah…you must be crazy