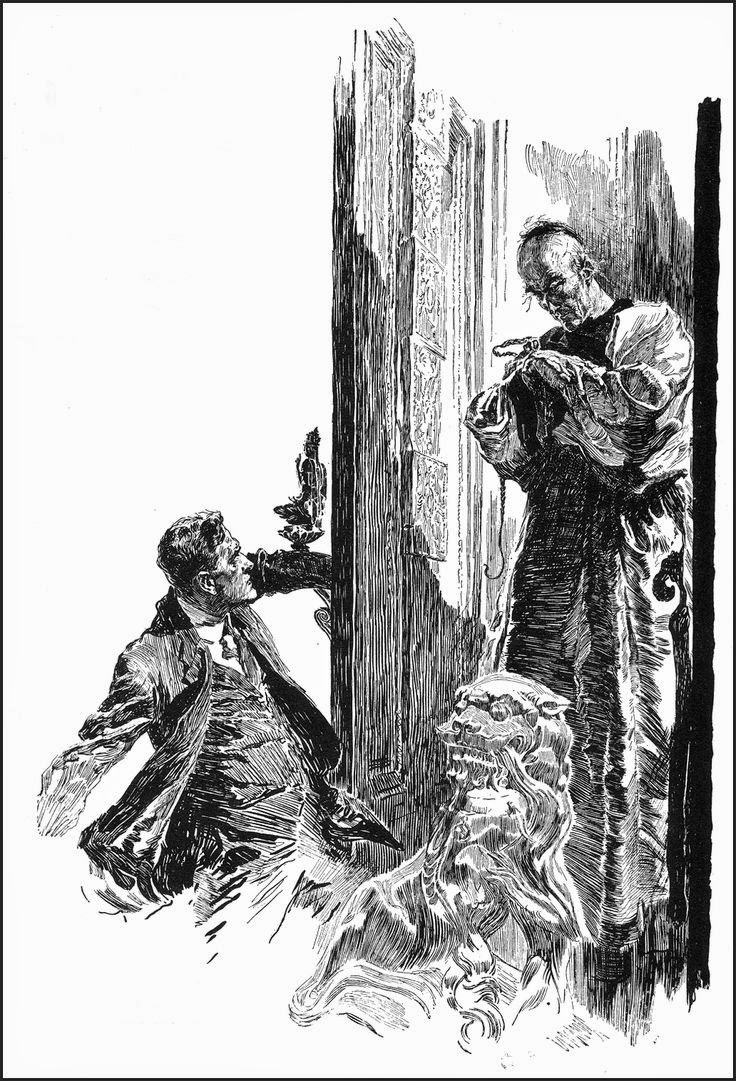

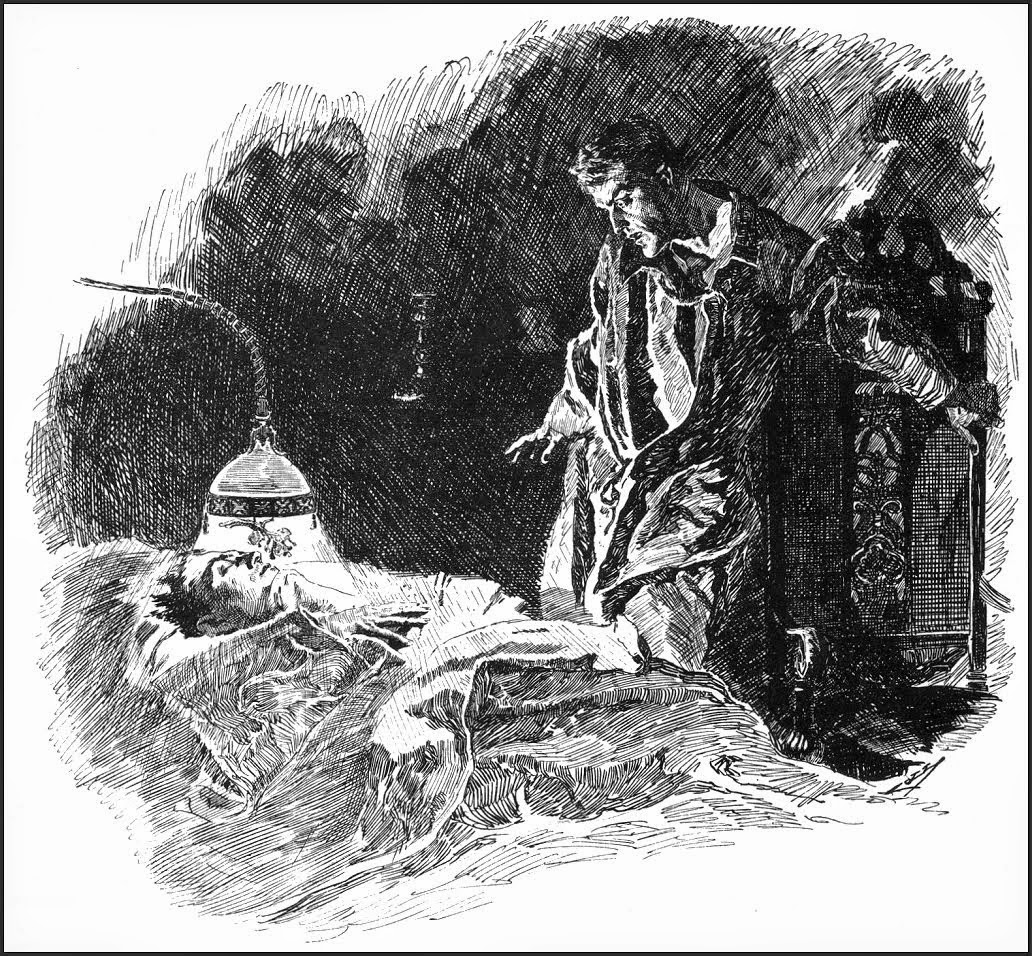

As is probably completely obvious in a lot of my work- particularly the black and white brush work- you will see depths and deeper depths that all belong to one of the true astonishments of ink drawing in early 20th century illustration, Joseph Clement Coll.

I first came across Coll’s work via one of two tentpole monographs on his work from Flesk, “The Art of Adventure”, and “Legacy in Line”. For anyone looking to see how with a simple quill pen captures universes, this is your guy. I keep the latter of the Flesk books always within arms reach of my drawing table and I always find something I never saw before in the work even after ten years of obsessive looking.

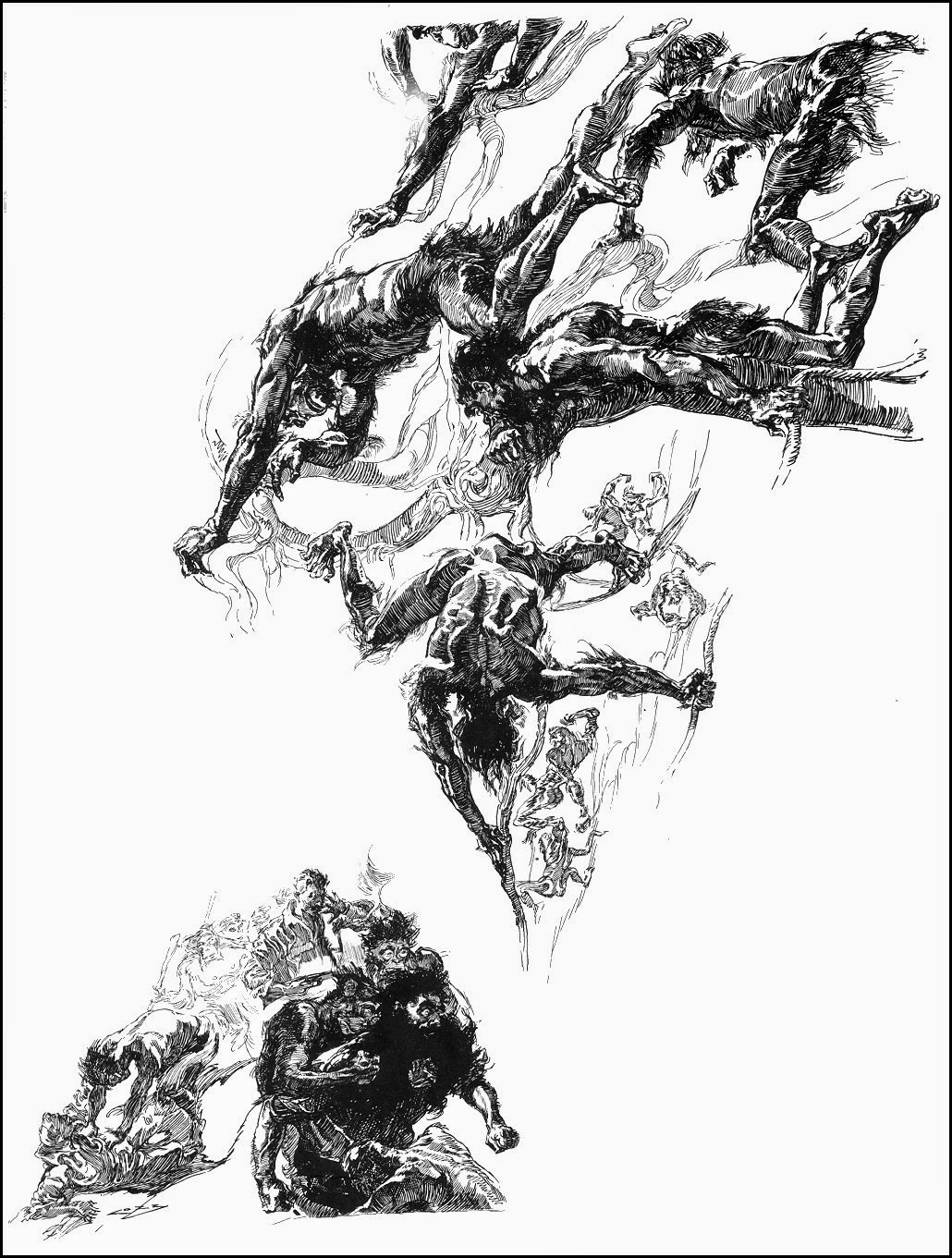

Just about around the era of Charles Dana Gibson, Coll takes a lankier fluidity to the more stilted historical style and goes deep noir. James Whale shadows and underly chins, bricks and stairs, in what would be for most of us a gaggle too many lines. For all the flurry of his drawing, even in their most abundant, there is not a line to spare. His sense of anatomy allows him to warp and exaggerate his figures without ever breaking the essential rules of its form. His compositions are so wild, scrawling up and around the text or title, they’re even a bit hard to know what you’re looking at until slots into focus.

To use such a scratching rigid implement to makes brushlike strokes continues and will always continue to amaze me. It’s the white whale you never want to catch, because then what? This was the Golden Era for illustration- not content or opportunity wise, not even by a long shot, but in terms of sheer mastery and the culturally responsive evolution of victorian formalism morphing into modernism, there is no more an exciting place to see how you do it right.

So, this week’s post is to you, J.C. Coll, top of my Holy Trinity of artists from this period-ish (Lyendecker and Rackham) and someone you really can’t see enough work by.

He's awesome! I love Rembrandt's and H. Kley's inks, but Coll hits that sweet spot in between- so cool! Thanks Greg!

Coll is definitely one of the greats. Sadly, an artist who never really got much recognition and one of my all time favorite B&W guys was Roy Krenkel. I have a monograph on him from i guess it would be late 80's early 90's called Swordsmen and Saurians. That has as much wear and tear on it as any Frazetta book i own-

Remarkable! Thanks for cluing me in to Coll – I'll keep an eye out for his collection. I love this inkwork.

Remarkable! Thanks for cluing me in to Coll – I'll keep an eye out for his collection. I love this inkwork.