Okay let’s face it, this is the kind of discussion that gets us all excited and nerdulicious, whether we’re artrists, car mechanics, surgeons or certified public accountants. We love our tools, we. love. them. We love to talk about them, we love to compare them, we like sharing them and evangelizing over them. Some of us jump from one new tool to the next others cling to our old ways like a life-raft in a stormy sea. I’ve never met a creative who couldn’t stop what they were doing to dive into the deep waters of fandom or hateful rage against a particular tool. We all have opinions about them and for the large part of the day, they are the only things we interact with in our lonely journeys to crafting our work. It’s natural and nothing to be ashamed of, and the bible doesn’t even say anything rude about it so it’s fine. Go for it. Hug your passion, cheer for your favorites. Your tools are your best friends and the only ones that really understand what you do. Take care of them and they will return the favor.

|

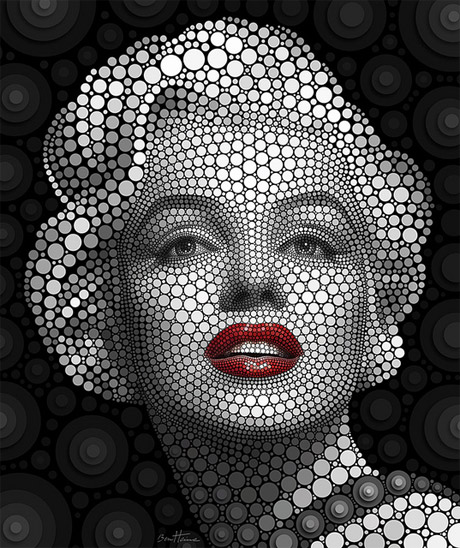

| Cyberman! |

Tools are mere extensions of the artists hand. it is as close as we will come to automating our hands to perform our desired tasks. Our open ended fingers are really just usb plugs for variable attachments we can use to make things, and the best tools are the ones that seamless blend into the flow of our intent like a natural extension of a finger, hand or arm. The relationship isn’t a one way street, though. We are guided nearly as much by what the tools do as what we tell them to accomplish. You use a charcoal stick to draw with and are given a pen, your drawings will change. The way you think about making a drawing will change. The longer you use it the more your style and approach and even creative problem solving will be changed by that pen to suit and exploit the pen’s needs and abilities. But as much as you may get feedback from this extension of self, you must always of course be in charge of it and learn how to use it to best serve your purpose. Obvious, I know, but surprisingly in need of repeating.

|

| The Shinoharas |

Can you take a brush and stab a canvas with it? Sure. Can you use a quill nib and pen to splatter on paper? You bet. Is it okay to scan a potato and make it in a planet on a piece of cardboard? Paint with boxing gloves and acrylics? Hell yes. While a tool may be designed for a certain task the way a car is designed to move forward and backward down a road, you are its master and can make it go wherever you want. That VW bus may not want to go off-roading in the muddy hills, but that doesn’t mean you might be able to coax that out of the thing. Same is true for your fancy paper, brush, canvas, chisel… in fact one of the great revelations come when an artist takes a thing and makes it do another thing with it. While there are a certain set of basic laws of gravity to a specific tool- a pencil cannot, say, fly an airplane- that doesn’t mean those laws can’t and shouldn’t be bent, pretzel-crazy to any end you can try and discover. Are bic ballpoint pens made to make comics? no, but I did that and I learned a lot about it- (mostly that bic pens are kind of awesome, entirely archival and are as close to pencil work as any pen can get). One of our assignments in school was to come in and for a week create or use something to make art with that isn’t a conventional art tool. It was a tremendous exercise simply in thinking outside of the usual art-school box of what and what is not possible with the tools we use. Turns out a baby-doll arm with a sponge lashed to it jammed on the end of a long pole can strikes some really interesting ink drawings as much as a bowl of ground up fall leaves and olive oil can give us some curious and compelling paintings. These were fun and granted, not an arbiter of new directions of my own art-making save for the value in jumping out of the box of conventional thinking where surprises may be in store.

When you really boil it down, it’s all just arbitrary that we have certain high and low schools of tool use. Oil paint is no more inherently valuable to making art than your butt is. It’s just been codified and used to create such a long history of masterworks that we put the medium on a pedestal and worship it as if it created the work all on its own. Carving from marble or carving from spam have no real difference in artistic value, but we would only put one in the MoMA as a lark. But we still assign value and hierarchy anyway, as dumb as that is. oil paintings are still considered somehow more valuable than acrylic paintings, regardless of who painted them or what they depict. Personally I find this a dopey way to look at art and I think is not something any artist should play in. Leave that business to the critics, and feel no shame in using mayonaise to execute your masterwork. If an alien disembarked from his ship and was posed this question he’d look at you like you had worms growing out of your nose holes. So forget about it. While the tools we use direct in some ways the paths we take creatively, they are no more or less valuable than any other. The only rules should be the ones you the artist makes. you are after all God on your own mountain and nobody tells god what he/she can and cannot do. Nossir.

One of the biggest mistakes in how we address and interact with art tool culture is assuming a piece of work is great because of the tools made to execute it. I myself will often look at a JC Cole piece or a Van Gogh or a Terry Winters painting and want to know what was used to make the piece as a way to understand how the medium was applied and appreciate the mastery of the chosen mediums. Sometimes it’s about how a mark was made and wanting to try it out for myself. This is what we do and should always do as artists. This is however different from wanting to know what tools were used because we mistake the tool for the artist in making the piece. I get asked often what kind of ink I use, or what particular pencils I like to draw with, and largely I think this comes from other artists responding to the marks made and wanting to try it on for size. Other times it’s clear the question is about trying to get the name of the exact thing so that they can go get one to do that thing for them as well. In practical artmaking this couldn’t be further from the truth. In digital this is far less so. But a $900 sable hair brush isn’t going to make a painting better int he hands of an unskilled artist anymore than a $2 brush will. I personally avoid overly expensive rarified tools because they come with such an expectation, I am just too neurotic to want to play with. My paper is cheap as are my brushes and pens for this reason. I do have a few nice premium handmade brushes, and I treasure the hell out of them not for what they are, but for what they do for me. I let my purebred award winning pug run right alongside my alley-mutts and they all get along swimmingly. And while I’m always happy to answer the question of what tools I use in particular, I will always presage that answer with the warning that it doesn’t matter what specific brand of whatever any artist uses to make their work. Owning a deluxe Moleskine sketchbook won’t make for better sketches than one you made yourself with a stack of newsprint any more than owning an airplane will make you a good pilot. You can make just as valid a piece of art from supplies bought at Michaels or a local hobby shop as can be had at Dick Blick or New York Central art supply.

One of the biggest mistakes in how we address and interact with art tool culture is assuming a piece of work is great because of the tools made to execute it. I myself will often look at a JC Cole piece or a Van Gogh or a Terry Winters painting and want to know what was used to make the piece as a way to understand how the medium was applied and appreciate the mastery of the chosen mediums. Sometimes it’s about how a mark was made and wanting to try it out for myself. This is what we do and should always do as artists. This is however different from wanting to know what tools were used because we mistake the tool for the artist in making the piece. I get asked often what kind of ink I use, or what particular pencils I like to draw with, and largely I think this comes from other artists responding to the marks made and wanting to try it on for size. Other times it’s clear the question is about trying to get the name of the exact thing so that they can go get one to do that thing for them as well. In practical artmaking this couldn’t be further from the truth. In digital this is far less so. But a $900 sable hair brush isn’t going to make a painting better int he hands of an unskilled artist anymore than a $2 brush will. I personally avoid overly expensive rarified tools because they come with such an expectation, I am just too neurotic to want to play with. My paper is cheap as are my brushes and pens for this reason. I do have a few nice premium handmade brushes, and I treasure the hell out of them not for what they are, but for what they do for me. I let my purebred award winning pug run right alongside my alley-mutts and they all get along swimmingly. And while I’m always happy to answer the question of what tools I use in particular, I will always presage that answer with the warning that it doesn’t matter what specific brand of whatever any artist uses to make their work. Owning a deluxe Moleskine sketchbook won’t make for better sketches than one you made yourself with a stack of newsprint any more than owning an airplane will make you a good pilot. You can make just as valid a piece of art from supplies bought at Michaels or a local hobby shop as can be had at Dick Blick or New York Central art supply.

These are the newest species in our arsenal and the most fraught and beneficial. I love tech, but I’m far from a tech savant when it comes to digital art tools- especially software and tablets and all that jazz. I don’t know that I could successfully make the kind of comics I make with out the editorial and layout qualities of photoshop, but that doesn’t mean a Wacom tablet makes any kind of sense to me. Tech tools give us an incredible new array of potentials and abilities and like the other tools, guide and shape the way we make. Digital tools are the most seductive, but contain within them the most restrictions and the most dangerous temptations. The restrictions currently come from of course the issue of power. no electricity no tool, no piece. A pencil will never run out of batteries, a brush will never get a glitch in its software. The more problematic issue I have is the lack of true mistakes and errors digital provides. It is a wholly binary universe- ones and zeroes that only allow for a more limited parameter of actions and as a side effects, surprises. The flip of a brush and an errant splatter of ink, the way oil interacts with some weird medium or surface, and the surprises that comes from it are basically absent from a digital medium. It’s a more controlled medium and as a result has within it less freedom. As it becomes more sophisticated and complex the illusion of freedom may rise up a bit more, and many digital artists argue with me about the happy accident experience, but still basic within it are some essential limitations of movement that carry within it some basic limits. The other concern for me especially is the coalescing of style to the tools used to execute a piece. No one else can mimic what Dave McKean does with a pen and ink, but you can come damned close with photoshop. There’s a seductive quality of the tools that have a character that limits the range of personality int he way the tools execute their jobs that I think causes a lot of digital work to have a similar look and feel. A photoshopped piece has a quality akin to most photoshop pieces, same for painter or whatever else may come along tomorrow or the next day. This is not to say digital is less valuable or qualitative as a medium, but these are limitations to watch out for. All tools have their limits, that’s part of their value: a pencil will not bend to perform the exact actions that a brush can for example. But the endless potential that digital tools provide can encourage us to mistake their push-button power for substance. It’s simply easier to hide poor line work, anatomy or composition behind all the bells and whistles in digital than it is on paper. It’s obvious when seeing it from the outside but can be sire-song crutches for the artist executing the piece.

These are the newest species in our arsenal and the most fraught and beneficial. I love tech, but I’m far from a tech savant when it comes to digital art tools- especially software and tablets and all that jazz. I don’t know that I could successfully make the kind of comics I make with out the editorial and layout qualities of photoshop, but that doesn’t mean a Wacom tablet makes any kind of sense to me. Tech tools give us an incredible new array of potentials and abilities and like the other tools, guide and shape the way we make. Digital tools are the most seductive, but contain within them the most restrictions and the most dangerous temptations. The restrictions currently come from of course the issue of power. no electricity no tool, no piece. A pencil will never run out of batteries, a brush will never get a glitch in its software. The more problematic issue I have is the lack of true mistakes and errors digital provides. It is a wholly binary universe- ones and zeroes that only allow for a more limited parameter of actions and as a side effects, surprises. The flip of a brush and an errant splatter of ink, the way oil interacts with some weird medium or surface, and the surprises that comes from it are basically absent from a digital medium. It’s a more controlled medium and as a result has within it less freedom. As it becomes more sophisticated and complex the illusion of freedom may rise up a bit more, and many digital artists argue with me about the happy accident experience, but still basic within it are some essential limitations of movement that carry within it some basic limits. The other concern for me especially is the coalescing of style to the tools used to execute a piece. No one else can mimic what Dave McKean does with a pen and ink, but you can come damned close with photoshop. There’s a seductive quality of the tools that have a character that limits the range of personality int he way the tools execute their jobs that I think causes a lot of digital work to have a similar look and feel. A photoshopped piece has a quality akin to most photoshop pieces, same for painter or whatever else may come along tomorrow or the next day. This is not to say digital is less valuable or qualitative as a medium, but these are limitations to watch out for. All tools have their limits, that’s part of their value: a pencil will not bend to perform the exact actions that a brush can for example. But the endless potential that digital tools provide can encourage us to mistake their push-button power for substance. It’s simply easier to hide poor line work, anatomy or composition behind all the bells and whistles in digital than it is on paper. It’s obvious when seeing it from the outside but can be sire-song crutches for the artist executing the piece.

That all said, digital has revolutionized the way we work and has made possible both for old weekend warrior luddites like myself to live in the middle of nowhere and work actively (thank you interwebs), and has changed the way I make my work entirely. As an example, I am not a color-minded fellow inherently- much more tonal in how I see things. Computers allow me to adjust and find color in a more direct and forgiving manner than I could do on a canvas. Being able to reverse a piece, crop it, zoom paste in fixes… all of these I could not now live without in a professional sense. When I used to make comics by gluing down panels or trying to get them right on the page, I can now not worry over and simply draw each panel separately to place as I see fit in photoshop later. Filtering my illustration work through a computer to send to a press or publisher guarantees color correctness and print quality formerly left to the folks at the press who used to have this power, and with wildly varying results. Digital processes are not going away nor are they substitutes for the basic skills needed to draw and make our work. They are simply the latest brush in the box, and while they can execute a wide range of things for us as artists it’s important to remain skeptical of their lilting songs, and not be seduced by their presets or filters that can take away individual voices for the sake of instant gratification or effect.

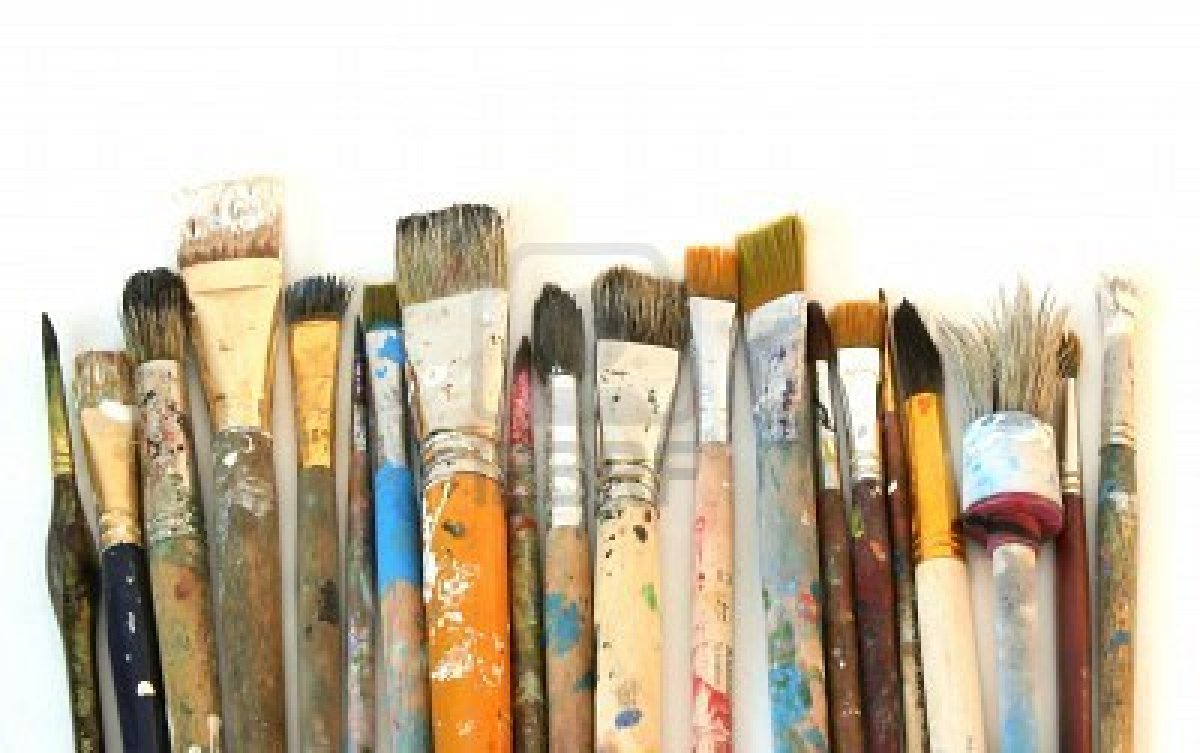

While I recognize this as an inherently subjective thing, I can’t help but feel it is also factual. For me the Palomino Blackwing is the best drawing pencil out there, and I feel like I can prove it. But I have met many who disagree. So as an addendum to the above statements of ignoring tool quality, let’s face it some are better than others. I like to use both cheap brushes for my work as I do my one of a kind hand made japanese brushes. But I won’t use just any cheapo brush because some just don’t hold a candle to others. One test for example, is to take that brush out and see if it has a natural point or a cut point. This will make a big difference in how that brush retains ink or paint at it’s tip. Flick that brush like you would your little brother’s earlobe- do little hairs start rising up out of it? If so is it one or a whole audience in standing ovation? If it’s the latter, put that thing down and move on. That means the brush will shed on you all the while you work with it and that’s no good for anything. The handmade brushes I use are the same ones I have been using for years, and for two of them, decades. This comes from both the quality of their crafstmanship, and also the care I bring to them. I make sure to hand wash and condition them at least once a week- (personally I like Pantene shampoo/conditioner for its all in one convenience and affordability). But really it doesn’t much matter. They are afterall, hair, and they get dried out and frayed and stiff and packed up at their bases with gunk just like your head-hair does if you don’t take care of them. The Blackwing sharpener exploits the best of the pencils in a way a regular or even electrical sharpener cannot. Making sure not to drop your pencils on the hard ground so it shatters the continuous shaft of lead inside, and keeping your erasers from drying out all contribute to make better work. If you use a nice gold tipped fountain pen- NEVER share it with soemone else as that particular way the nib is worn to your own manner will be ruined by another the same way buying a used loafer will feel bad on your feet. Even my cheapest materials get treated with the same regard as my most precious because when it’s go time, they all are expected to do what I command them to do, no matter what neighborhood they come from.

While I recognize this as an inherently subjective thing, I can’t help but feel it is also factual. For me the Palomino Blackwing is the best drawing pencil out there, and I feel like I can prove it. But I have met many who disagree. So as an addendum to the above statements of ignoring tool quality, let’s face it some are better than others. I like to use both cheap brushes for my work as I do my one of a kind hand made japanese brushes. But I won’t use just any cheapo brush because some just don’t hold a candle to others. One test for example, is to take that brush out and see if it has a natural point or a cut point. This will make a big difference in how that brush retains ink or paint at it’s tip. Flick that brush like you would your little brother’s earlobe- do little hairs start rising up out of it? If so is it one or a whole audience in standing ovation? If it’s the latter, put that thing down and move on. That means the brush will shed on you all the while you work with it and that’s no good for anything. The handmade brushes I use are the same ones I have been using for years, and for two of them, decades. This comes from both the quality of their crafstmanship, and also the care I bring to them. I make sure to hand wash and condition them at least once a week- (personally I like Pantene shampoo/conditioner for its all in one convenience and affordability). But really it doesn’t much matter. They are afterall, hair, and they get dried out and frayed and stiff and packed up at their bases with gunk just like your head-hair does if you don’t take care of them. The Blackwing sharpener exploits the best of the pencils in a way a regular or even electrical sharpener cannot. Making sure not to drop your pencils on the hard ground so it shatters the continuous shaft of lead inside, and keeping your erasers from drying out all contribute to make better work. If you use a nice gold tipped fountain pen- NEVER share it with soemone else as that particular way the nib is worn to your own manner will be ruined by another the same way buying a used loafer will feel bad on your feet. Even my cheapest materials get treated with the same regard as my most precious because when it’s go time, they all are expected to do what I command them to do, no matter what neighborhood they come from.

Really enjoyed reading this post.

I wonder, percentage wise, how many muddy color readers are all or mostly all digital. I wonder how many have literally never worked in any traditional medium except standard yellow #2 pencils and ball point pens.

I've been a die hard Castell 9000 fan. But will definitely try the Palomino Blackwings.

Traditional mediums users?? *raises hand* I appreciate the flexibility of digital programs like Photoshop and such, but for me, there's nothing quite like pencil and ink strokes and watching watercolors blend. Good post. Always like those images of rugged, experienced, well-weathered brushes.

I think that number is growing daily. I certainly have my preference in the digital v practical thing. Really it's just a new tool, and can be used to blow past conventional boundaries as we wee with Karla Ortiz or Sam Weber or James Jean. I think digital's biggest two dangers are 1: that it may encourage skipping the learning of practical drawing that makes one's digital work so much more substantive, and 2: that the inherent tools and filters within it are so seductive as to limit the desire to push boundaries with it.

Those Castells are nice, I think you'll find the Palomino to be like liquid comparatively.

That tactile quality of practical tools, that direct reberb you get from the thing you're working on/with makea a big difference for me. The kimd of exhausted i feel at the end of a day working digitally versus that same day drawing… World's apart. But even so, as I said The 'puter is a wholly integral part of the work in the studio now. I could never meet my deadlines without it.

Well, as someone who has spent the past ten years working on an open source digital painting application (https://www.krita.org), I'd like to argue that “digital” isn't a tool like “oils” — every application is a completely different tool. They might share some algorithms, but a discerning eye can see the difference between something done in Photoshop, Painter, MyPaint, Krita or Sai. (Unless the strokes have been completely blurred together, of course.) Krita has a dozen or so different brush engines, which use different algorithms and have different levels of serendipity — all those are as different tools as pens and pencils are.

What an entertaining article.

I grew up alongside the birth of the computer age and was basically weaned on digital art.

Many years later I'm making a more serious foray back into traditional mediums and I'm finding them so much more enjoyable to use.

I think there's another hidden danger of the digital age is that it has sped up everything, including the creative process; what may have been expected to happen in a month now is expected by Friday. It may have it's upsides but I don't really think this is healthy for art-making.

More on-topic, the pencil I'm never without a supply of is the Cretacolor Nero pencil (med or soft), drawing with this baby on smooth paper is an erotic experience.

Check out Jetpens.com's guide to picking a pencil http://www.jetpens.com/blog/guide-to-wooden-pencils/pt/633 . I really fell in love with the Uni Mitsubishi 9850, but also very much like the Palomino Pearls (they have a great selection of Palomino pencils, too http://www.jetpens.com/Wooden-Pencils/ct/620?&f=be9269dc228035bc1f1a95fe60931212 )

Nice post!! Thanks for sharing.

Dermology anti aging Serum

dermology anti aging cream

Dermology

dermology hair removal cream

dermology hair removal cream

dermology hair removal cream

dermology cellulite reduction cream

Xtreme No

Xtremeno

hgh energizer

The tool is not the Artist! U’re so right! Really inspiring article, thank U! Love to read stories like this. And love to search reviews of top-rated art products like https://wowpencils.com/best-acrylic-paint/. They both help me to make a choice and do my pic-drawing easier