An important thing to remember at the beginning of your commercial art career is that everyone had to start somewhere. In the same way it’s easy to admire a finished painting and overlook the long chain of steps it took to get there, it’s easy to look at the success of other artists and forget that it is almost certainly built on a humble beginning. We remember their big moments, but we often don’t even know the early steps. And it’s vital to consider this, especially for artists who themselves are paying those early career dues and might be feeling the common frustrations that they’re stuck and never going to get any further, or that they just can’t seem to connect with that white whale client they’ve been chasing for years.

Remember that most who came before you spent time where you’re at, doing what you’re doing. Speaking personally, my early jobs were essentially $100 card art and working with dodgy, low pay indie projects. And over time, I’ve discovered a few things that helped me climb past those plateaus and improve both my prospects and my chops.

Disconnect the rate from the work

This was my first big revelation when doing low rate card assignments. I took them because I was eager for any job, even if the pay wasn’t livable, and I didn’t have the portfolio to get anything better. But looking back, I also knew the compensation was unreasonable and resented it, which lead me to approach each piece with a mindset to get the job done as quickly as possible and still meet minimum standards. This meant cutting corners in a number of ways. Maybe the most significant was complacency for the first idea I had for each assignment without pushing further. You can get lucky sometimes with that, but mostly it leads to boring, seen-it-before results. Executions were rushed, compositions half baked, every aspect was well bellow my potential. And many months later, when the money was long since spent and the art was finally released… I didn’t want to show it. It wasn’t work I was at all proud of. Which meant it definitely wasn’t going to help me find something better.

The client was still hiring me though, and I decided to stop giving them what they were paying for and really put my all into giving them best I could give. Pushing myself for better concepts and compositions, more ambitious approaches, more thorough reference shoots, and more time to actually execute each pieces. And believe me, I definitely resented how my hourly rate broke down as a result, but I also realized that it was investment. It was for my own benefit. If I wanted better opportunities, I needed to make work to match. Kind of like dressing for the job you want to have and all that. I decided, and have been mindful of it ever since, that once I agree to take on a commission, I put the money out of my head. Money is temporary. The final result can last a very long time and, good or bad, it comes with no disclaimers. My prospects improved significantly once I started, as I saw it, overshooting their rate, and it wasn’t long before I moved on from that underpaying client.

Make work that you love

This comes in two flavors. One is to put your heart fully into the work you do and always find something to love about each piece. I don’t care if it’s tapping a deeply emotional moment in your life or just that you’re really going to nail the realism of some drapery folds. People like to see work that was created with genuine love and passion, and they can tell when it’s missing. Finding a way to infuse that love into an uninspiring brief is the real trick. Ultimately though, it’s also one of the things that is required to do this job well. As you do begin having more opportunities, you’re able to be more selective in pursuing work that doesn’t feel like an uphill battle to connect with.

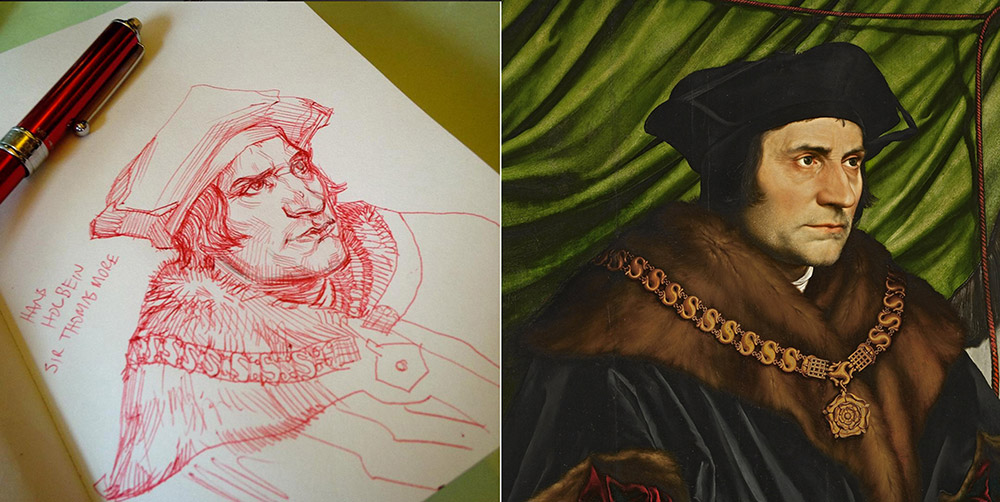

Perhaps more impactful than this though, and something I’ve touched on several times in past articles, is to make personal work that really explores what you find exciting, important, and fulfilling. The big milestones in my early career portfolio were all non-commissioned pieces, and doing personal work continued to shape what would make my work stand apart even once I was getting established. When people remember you because your work has a vibe or mood or angle which is personal and specific, they’re going to hire you to keep doing that. Don’t do someone else’s thing, be the best person there is at doing YOUR thing.

A “no” is free

Getting your stuff out there has never been easier, which creates a weird paradox that makes it very hard to be noticed. If you’re only promoting on social media, you’re up against a lot of noise. Which is why I still subscribe to two oldschool methods of promotion: direct mailers and in-person meetings.

Direct mailers are simple. It shouldn’t take much research to find names of art directors you’re interested in (credits in annuals, company website, word of mouth, social media posts, etc.) and the company address. Sending a physical sample, be it a post card or a mini-portfolio booklet, has a number of advantages over instagram posts. For one, we all know to NEVER tag art directors on social media, so you have to hope they passively find you. And if they do, the image is likely small, scrolled over, and forgotten in a second or two. Even if they see something and say “this person is great, got to keep my eye on them!” it’s quickly out of mind. A physical mailer is something you’re putting in front of them (and it’s not considered rude so long as it’s not more than once every 3-6 months) and they engage with and they can actually keep on hand. The first hurdle to getting hired is that an art director likes your work. They second and equally important hurdle is that they remember you when the right job comes up.

In-person meetings are getting trickier, especially depending where you live. Once upon a time, everyone just moved to where the industry was. For so much of illustration that was New York. But, of course, everything is spread out now and many of us work for people and never actually see their face or hear their voice. So if opportunity arises, grab it! Conventions, workshops, openings, industry parties… making a human connection can really be a boost in making an impression. In some circumstances like scheduled portfolio reviews, you could not ask for better access. You get to receive feedback on how your work can best fit their needs and you can and should have some kind of sample or card to leave with them to remember you.

To say “a ‘no’ is free” is to say you lose nothing by asking. OK, I suppose printing postcards and attending conventions costs something, and workshops likely cost a fair bit, but the core idea is you need to risk putting yourself out there. I’ve heard a story that the artist James Bama moved to New York with aspirations to work in advertising. He had a list of agencies and decided to try getting in at the very best one first and, if rejected, work his way down the list from there. Whoever hired him, he wouldn’t wonder if he could have done better. He was fresh our of school and was hired by his first pick.

I think a lot of us have an attitude to punch our own weight. We feel we’re at a certain level and are shy to be seen reaching beyond it. But we also know that people are often poor judges of their own expertise, and aiming low keeps you low. That’s why a “no” is free. If you don’t ask, you’ll never find out.

Know what you want

It sounds like the easiest of all points here, but I think this is the one I still struggle with the most. Maybe because it tends to change over time. The best way to make progress in anything is deciding what you’re really after and attacking it with steady focus. If that means working with a specific client, then you need to learn what that client needs in an artist and demonstrate to them that you are exceptional at it. If it means showing with a particular gallery, bring your work, prices, and pitch skills to their level and get face to face with their curator. If it means building your own property, then… find out whatever the people who are really good at that do and make it your first second and third priority. (Sorry, I won’t pretend I know the road map on that one.)

If you’re all over the place in your ambitions, it’s going to be hard to get anywhere. This obviously leads to confused portfolios, but it also can induce a kind of paralysis. Not being sure which way to move or what to prioritize. What most often happens then is coasting, which is a strategy for stagnation. If you’re feeling torn in different directions or unsure what path to take, you just have to make a choice and take the first step. It might not lead where you ultimately think. It almost certainly won’t. But it will lead to the next step, and the next after that, and that’s how you ultimately move forward.

Just what I needed to hear. Thanks.

Hello David,

thanks for a great article, I found the last hint especially useful (make a decision to move forward and avoid stagnation).

Insightful post, David, thank you for writing it! Was especially encouraged by the advice to not do someone else’s thing, but be the best there is at doing your thing. Great reminder.

It’s true about ‘instagramming’ .. we all are just a bunch of jpg’s, easily forgotten in moments.

Thank you for writing this! It’s nice to see that ‘old school’ paths are preferable than just relying on social medias.

It’s good to say “do your own thing,” but I have trouble imagining where my work would fit into various markets that interest me. I look at the artists they’re using and I don’t see myself as fitting in. How would you counsel artists who are having this sort of trouble? My ambivalence about whether I fit in or not makes me hesitate to reach out to art directors.

Thanks for writing this post. I motivates me to finally clean up my portfolio and pick the direction I have been craving at for years. I just needed to hear it from someone I admire to get it done.

Great post, thank you ! I too needed to hear it, especially the “know what you want” part, always evolving.