The rhythm of a shape – in this case the shape of a crowd of figures-is designed to be in counter rhythm to the sillouette of the distant hills. It helps to make a viewer “accept” this loosly painted image as a representation of reality. The shape could just as easily be a reclining figure or a wave on the beach- the same principles apply.

I went through several areas of study at UC Davis before I became an Art History major. The classes where people actually made “art” seemed to be irrelevant to what I was interested in… so I spent alot of that six years looking at art, thinking about what I liked, and what I didn’t like, and what my future in the art world could possibly be. I couldn’t really imagine myself as anything like what I imagined a real artist was. Once I graduated, I followed this up with two years in the work force- the last time I had a “real job”– during which time I learned a lot about what I didn’t want to do, and hatched an escape plan that included escape from my job and going back to art school a second time, to study illustration. During that two years, I spent most evenings working on a “portfolio” that I could use to get into grad school. I was felt pretty good about myself until I went to my first drawing class in grad school, with lots of undergrads, and immediately realized that my drawings were, without a doubt, the worst in the class. I underwent a crisis of confidence…and thought about cutting my losses and quitting then and there. The teacher, fashion illustrator Justine Limpus Parish, came up behind me and said two words which had a transformationa effect, and which became a mantra to me, “rhythm and counter rhythm”.

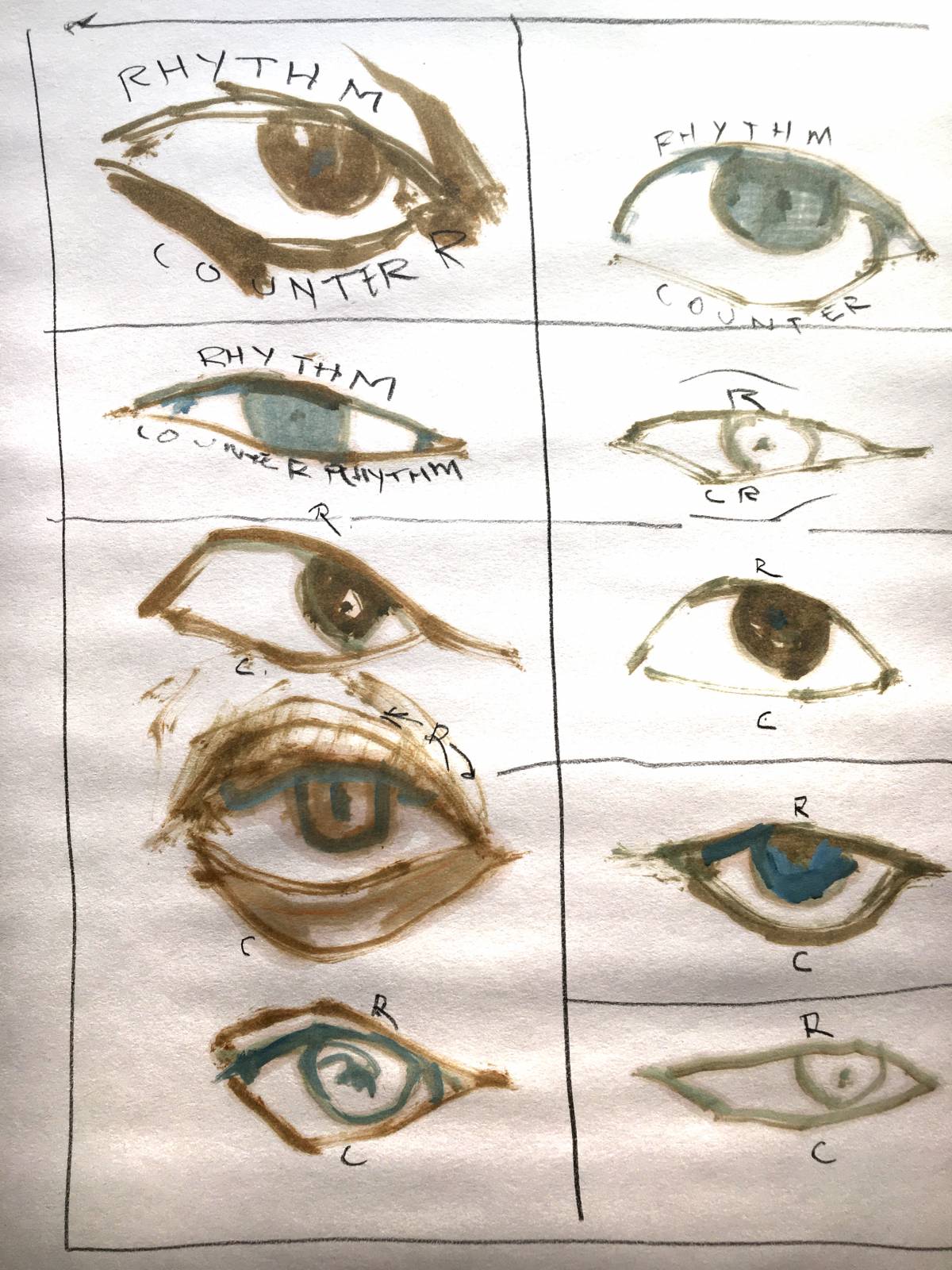

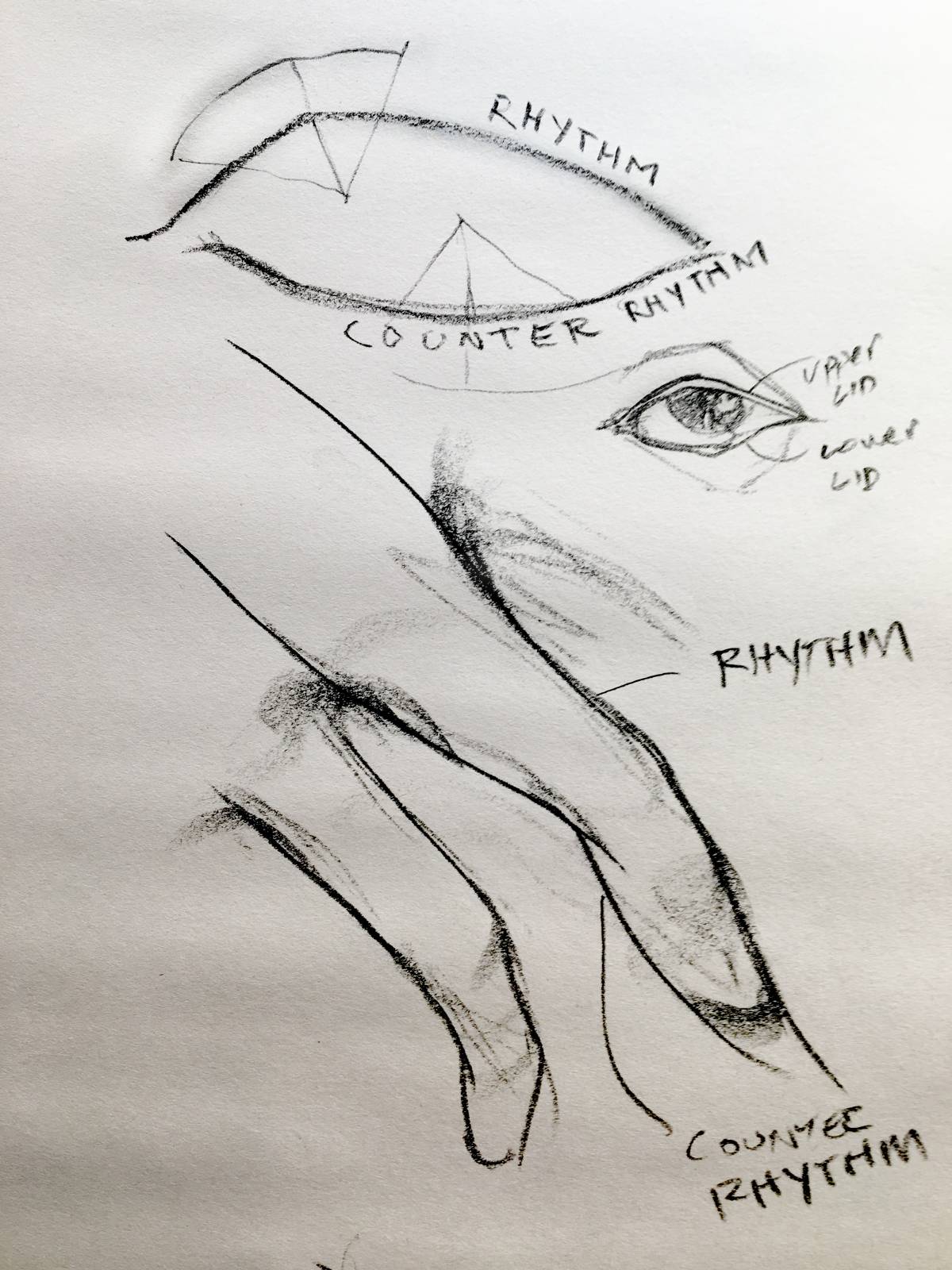

Understanding the relationship to one line to another – in this example, the curve of the upper and lower eyelids, is a key to expression and likeness

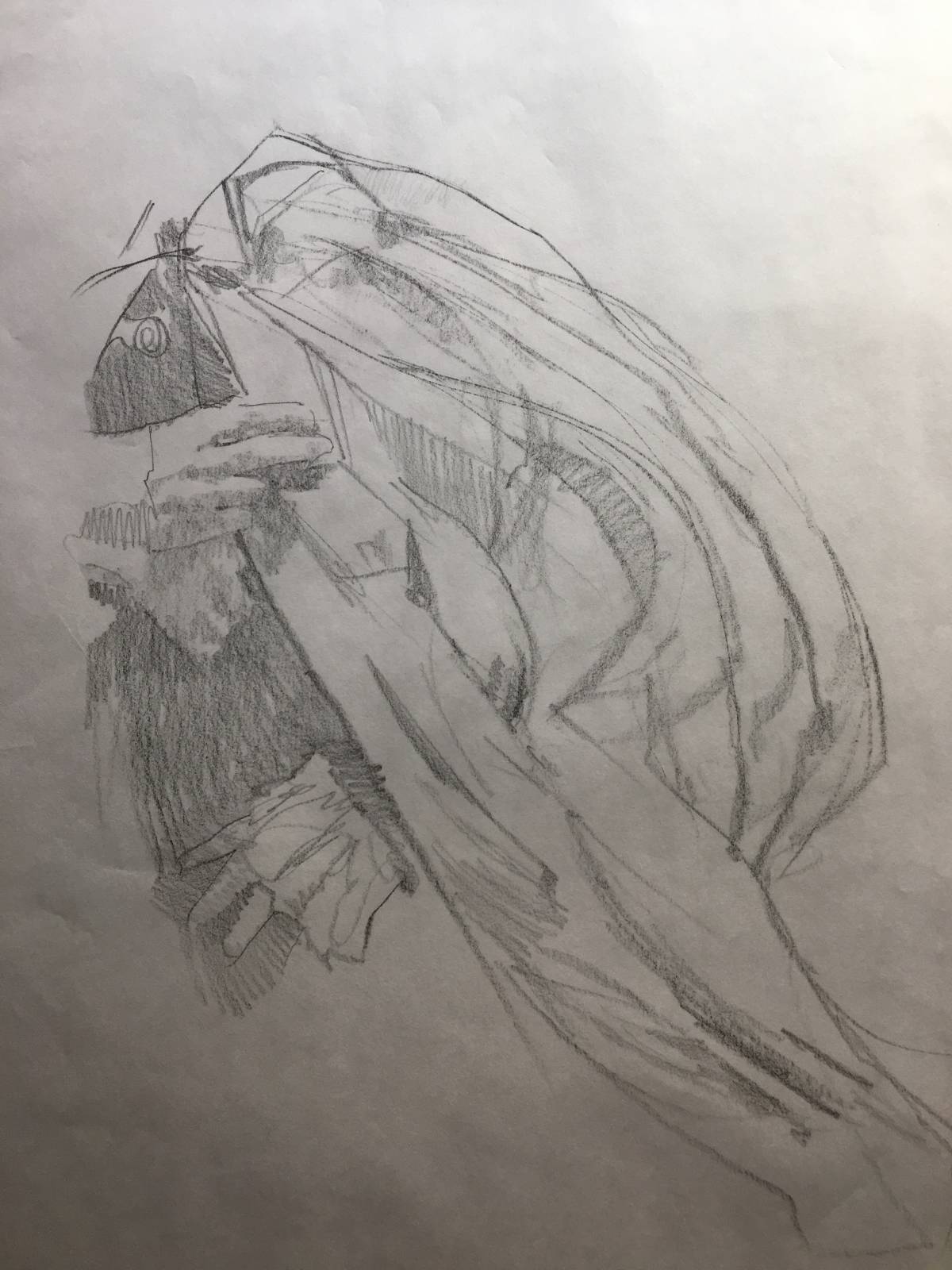

the flow of fabric, the swirls of snow, the hair, the figure, every line is related to every other line. Not only will it help the image look naturalistic (assuming that is your goal- it is not always!) this can also be a tool to get the viewers to look where you want them to look and to control the impact your image will have on them..

She told me to look for the relationship of shapes, curves planes and edges to each other, and pointed out that looking for rhythms (and counter rhythm) in this spatial relationship was key to understanding observational drawing. The phrase opened up a whole new way of seeing to me and I can honestly say that this simple phrase was the basis of one of the greatest lessons I ever learned- superficially simple but deceptively complex, a lesson I am still learning. It applies to almost everything. Maybe I can pass a little of this onto you.

If you think of a limb, an arm or a leg, a neck, a finger, an ankle-think about the profile, the silhouette edge of one side, and then think of how it relates to the OTHER side of the shape. However, we choose to express these edges, the key is to have a rhythm of line and shape on one edge that is in counter rhythm to the line on the other side. The apex of one curve should not be directly across from another, it must be offset. The shape of the curve must be different. If you are insensitive to these rhythms, t=your line will be dead, symmetrical, unnatural. Once I realized the truth of this, I started to look for it, and my drawing immediately improved.

Is the girls left arm coming towards you or going away? the relationship of the curves on the top and biottom edges of her arms is how you know

We can extend this into almost any part of art if our goal is representational interpretation of reality, particularly when we are interpreting nature- which is filled with examples of this principle. A tree grows, it twists towards the sun, through the seasons, it fights to counteract the forces of gravity erosion and climate, and the tension and history of the struggle is expressed in every twig all the way to the trunk and roots. When we draw or paint it, if we are mindful of these forces and look for the asymmetrical forms that express the tree’s existence, we see it’s likeness, and we can accurately draw it.

My wife and I recently began Tai Chi classes, and I was surprised to hear my teacher talking in many of the same ways. For example, though I can’t pretent to understand any but the simplest of principles, the principle of Yin and Yang is not only of balance but of tension. In a body, one muscle pulls one way and another muscle counteracts it. The two muscles are not the same shape, they displace different amounts of space, we need to draw them differently, even if we can’t see them, we now they are there. The asymmetry is what makes the symmetrical impression work. Does that make sense?

the horizon has to be off center – or the picture is cut in half and by being symetrical would be out of balance

Many of these principles in Tai Chi are at work in observational drawing- as well as other art forms, like music. Thinking in terms of rhythm and counter rhythm was a key to the development of modern classical music -the baroque period gave way to the romantic era of music in part when composers began to experiment with using space between notes as a flexible element. Instead of straight rhythm pattern (baroque) the variance of space (think of impressionist composers like Ravel and Debussy). The use of the space gave a composer a new tool to make more expressive music. We can do the same with our artwork.

One thing we need to do is to be constantly aware of the need to think of every line in terms of rhythm and counter rhythm. A simple place to begin is to think of a curve as an “s”, not a “c”, a “C” would only happen if the curve the “S” describes goes behind another shape.

I also learned that, at least for me, using my whole body to drawmade it possible to express these rhythms more clearly- and I learned that I can only draw or paint that way if I am standing up.

Another way it can be used is in the composition of painting, expressed as use of negative space, and of the tension between the elements of the composition: the elements -figures etc., the negative space, the place where there ARE no elements, and the edges of the composition.

Think of your painting like Japanese Zen Garden-the rocks are the figures, the sand is the negative space and the sides of the garden are the third element. The arrangement of these elements in harmony with nature: when we see one of these gardens we know there’s something special there. We are reacting to the gardner’s sensitivity to the rhythms and counter rhythms of nature. If we incorporate this thinking into our painting our audience will have a better reaction too.

It’s all around us- the first step is to know it’s there, the second is to look for it, the third is to incorporate it. You may be surprised to find out that it could have a transformational effect on your work. Maybe it will help you make something no one else has seen before…but they will know it has something special in it.

Excellent article! Thank you.

Very informative. Thanks!

That horse and rider painting is so beautiful. Robert, I love your work! Hello from North Carolina – hope to see you again, soon.

Thanks Kyle! Hope to see you soon, maybe at iCon