Many artists describe their work as “narrative” – that there is something more to discover underlying the imagery. Illustrators by nature deliver visual storytelling that conveys a specific message or idea. But what about sculpture?

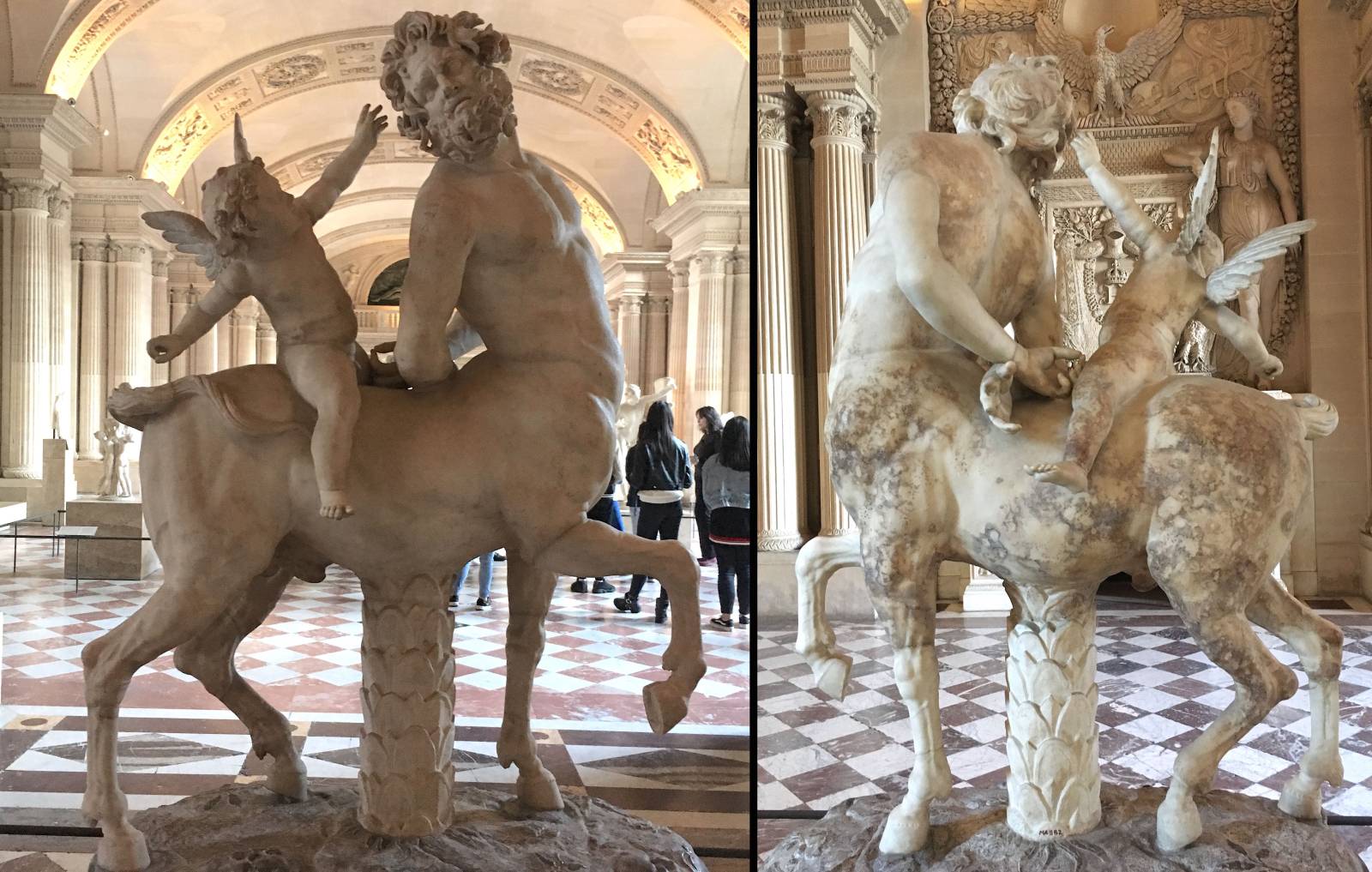

One time wandering the Louvre, in an obscure upstairs room, Colin and I came across a bronze sculpture by Theodore Gechter – “Le Combat de Charles Martel et d’Abherame, Roi des Sarrazins” (The Fight of Charles Martel and Abherame, King of the Saracens).

The broken shields and shattered lances tell what happened in their first run at one another. Perhaps this was when the Saracen was unhorsed, resulting in his mount falling to the ground. The Saracen’s empty scabbard and snapped sword at the front indicates the next failed attack.

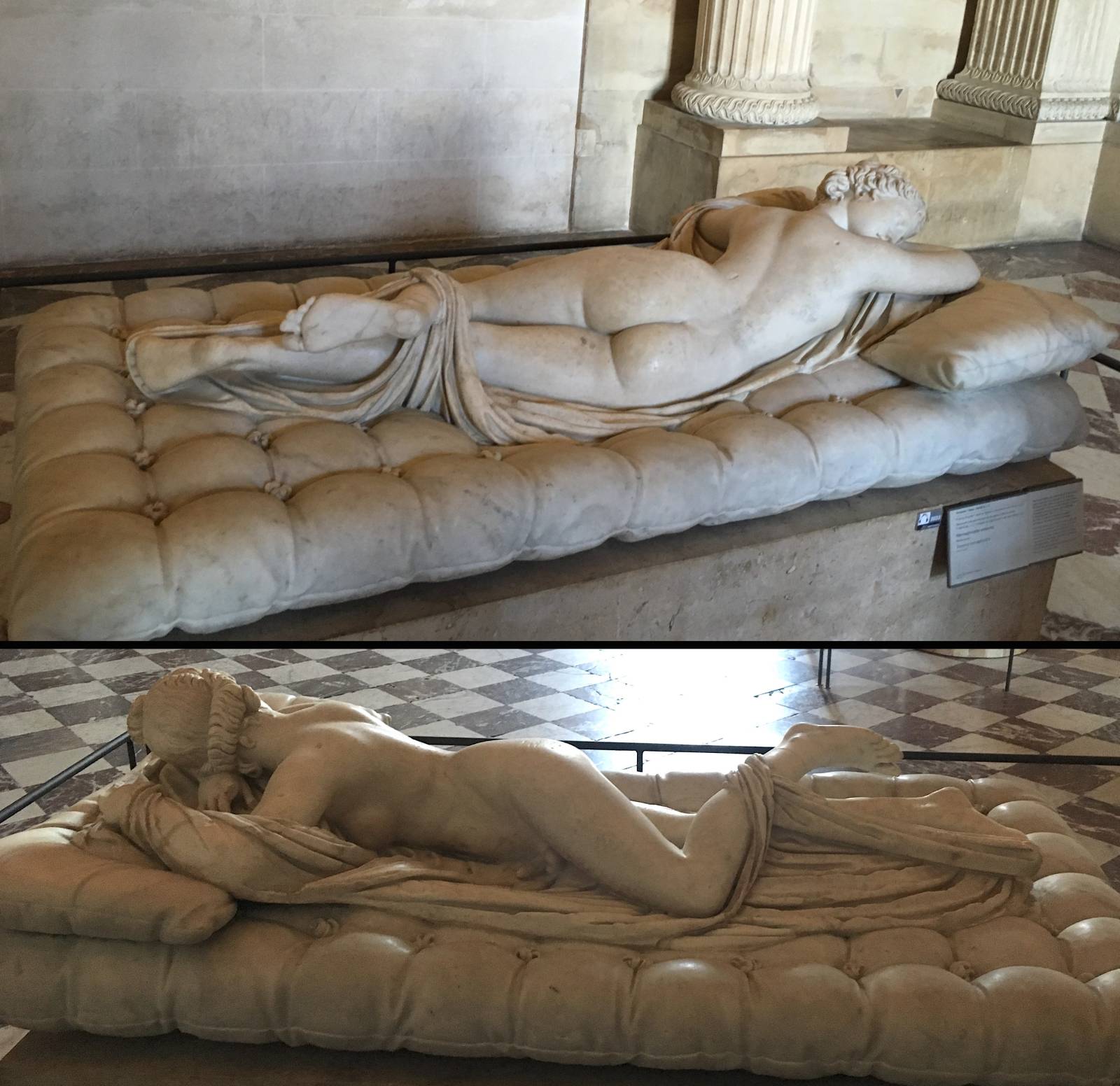

Sculpture is uniquely positioned for narrative interpretation given that we can add elements that are only visible from various viewpoints that either enhance or dramatically shift the story.

I’ve mentioned this Ron Mueck sculpture before, but it perfectly illustrates the way a well thought out sculpture can add an intriguing twist for the curious viewer who will walk around to see the back side. From the front, we see a young couple snuggled up next to each other – seemingly a very sweet composition. From the back view however, the boy is gripping the girl’s wrist in an aggressively uncomfortable looking position. Seeing this makes us return to the front view for a closer look. With the new information, we now see the pinched lips, the downcast eyes in her expression and the tension in her left hand – the story of the piece is completely altered. The artist has just taken us on a journey.

For “Tiger Man,” a collaborative sculpture, the story telling components are more subtly suggestive. Colin added relief patterns and embellishments to accomplish a couple things: blend the transition between human and animal, while adding a tattoo-like feeling that brings interest to the surface. He wove prey animals into the designs in keeping with the tigers’ status as an apex predator.

On “The Execution of Lady Liberty,” the text begins on her face with quotes featuring the ideology our country was founded on – words from the Declaration of Independence, the preamble to the Constitution, the national motto, and Emma Lazarus’ poem from the Statue of Liberty- all momentous words that created a powerful new reality: “We hold these truths to be self evident – that all men are created equal”; “E Pluribus Unum – Out of many, one”; “with liberty and justice for all”; “United we stand, divided we fall” and more…

The words merge around her shoulders into mostly contemporary quotes that document the anger, despair and intolerance being expressed in the current schismatic milieu we appear to have come to. Once people can be convinced that others are somehow inferior, detestable or in some way undeserving of the same liberties and freedoms, it becomes easy to begin to eradicate the rights of the communities that are “different” as they begin to be viewed as undeserving of the same consideration and compassion. Rhetoric that dehumanizes, de-legitimizes or objectifies another race, belief structure, culture, gender, orientation or lifestyle choice is the first step.

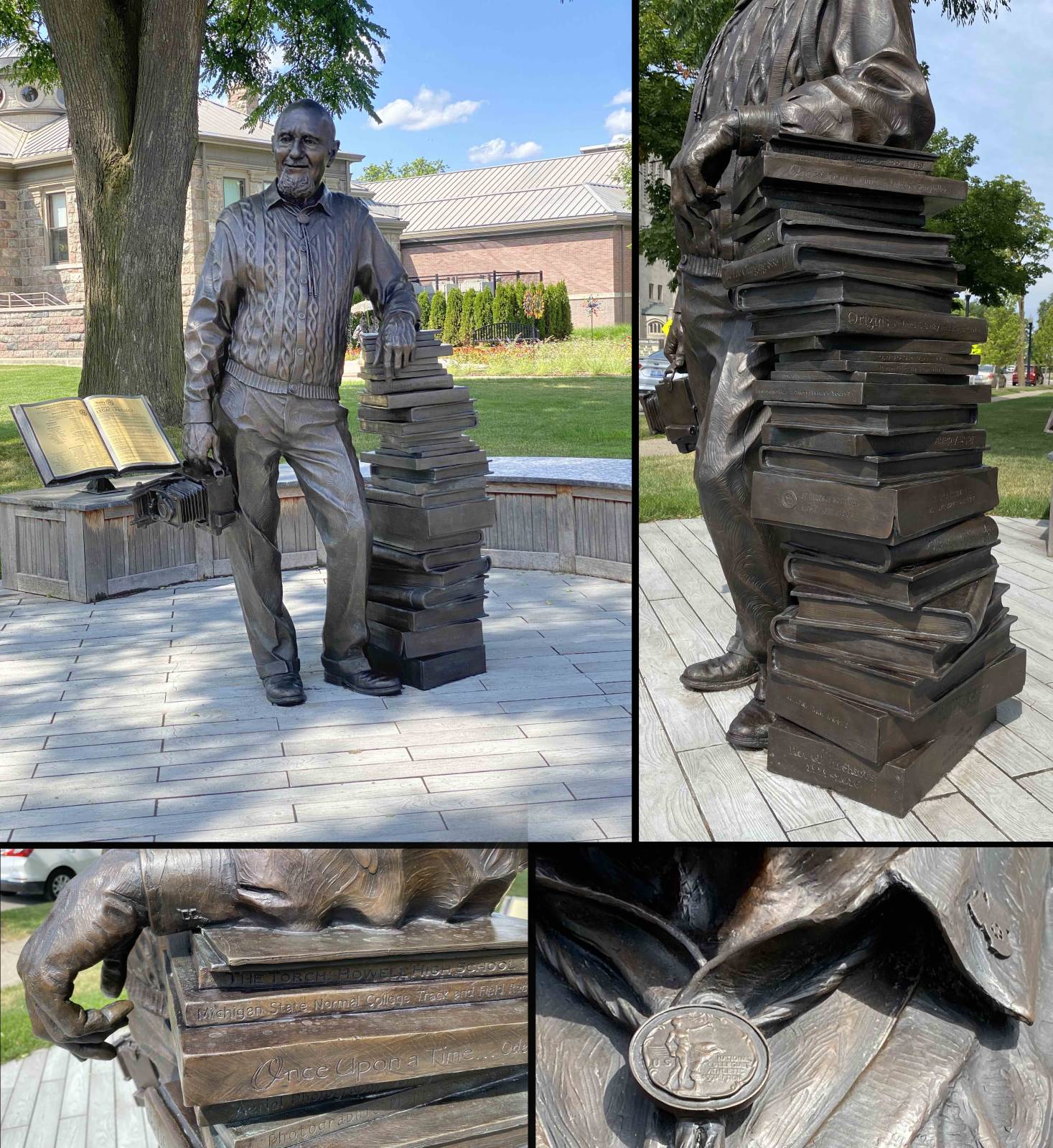

The book stack is a nod to the Carnegie Library where the statue resides, and contains titles representing the myriad facets of his life, accomplishments and contributions including books he wrote, books that inspired him, hints pointing to people who helped him on his way, metaphors symbolizing defining moments and imaginary titles representing stories he told that were familiar and fond memories for the community.

As an interactive element of the monument, we included over 60 of these “Easter eggs” – symbols and stories that members of the community will find and share tales about for decades to come, thereby perpetuating Zemp’s legacy for years beyond the lives of those who knew him.

The moon itself has long been associated with water imagery and the sea. From the sea was born Venus, the Roman goddess of love and beauty who also symbolized femininity and fertility. For this piece, we blended attributes connected with Venus, the sea, the moon and the Moon Hare.

Viewers are encouraged to walk around the piece to interpret the full story. Capitalizing on the narrative capabilities of sculpture in the round, the imagery on the back side of the piece brings to mind the imagination-stirring delight of finding a shell on the beach and “listening for the sound of the ocean” there. Taking this bit of reverie a step further, we create a moment of the “great reveal” where the viewer looks inside the shell to discover a hidden world that reveals the Moon Hare, sheltered within a wave, coming into being, complete with a hand-hewn stainless steel crescent moon.

Wow, this article is a real eye-opener! I never knew sculptures could tell stories in such cool and unexpected ways. The way you explained the details in each piece made me feel like I was right there, walking around them and discovering their secrets. From hidden “Easter eggs” in public art to the fascinating story of the Moon Hare, it’s clear that sculptures have so much to say. Thanks for sharing this with us; I’m now looking at sculptures in a whole new light!

Thanks for taking a few moments to share in some of the things about 3D that we find delightful, Nia! We often find that the more time we spend engaging with an art piece (2D and 3D), the more we “little secrets” we can discover. 🙂