In September I received a call from Tim Underwood’s wife, Rebecca, letting Cathy and me know that Tim’s health had taken a serious downturn, that his doctors had given him a matter of weeks to live, and that he wanted me to write his obituary.

Yes, it was a difficult call to receive and for Rebecca to make.

I had known about Tim’s fight with cancer for years, but I always somehow believed that if anyone could beat the odds it would be him. We had been periodically talking on the phone about his condition (we had spoken before and shortly after he had been admitted to the hospital) and, though he’d had challenges, he was encouraged by various treatments that had been developed.

In the back of my mind I always understood that Tim’s time was limited, but I never really wanted to accept it. We’d known each other for nearly five decades and I wasn’t really prepared to try to describe his life and our relationship in a few words. But, ready or not, I had to: it’s what friends do.

Today in Fairfax, CA, his friends and family are gathering for a memorial; what follows is my very slightly modified remembrance of Tim that will appear in an upcoming issue of “Locus.”

—

Tim Underwood 1948-2023

So. How best to describe Tim Underwood to those who didn’t know him and how to reminisce with those who did? Let me say it up front: it ain’t easy.

Because, honestly, Tim was incredibly complicated. He was a mystery in many ways, not deliberately so and not in an effort to deceive, but simply because he liked observing, listening, and talking about everything other than himself.

Tall, whipcord thin, soft-spoken and thoughtful, he was laid-back in that Northern California way (like The Dude from “The Big Lebowski,” his approach to life always seemed to be “Tim abides”). He was a voracious reader (and an expert on the works of Jack Vance and J.R.R. Tolkien), kind to a fault, stubborn as hell when he chose, slow to anger, and quick to laugh. He wasn’t the least bit religious yet was very spiritual and deeply interested in Eastern philosophy; for a brief period he changed his name to “Yoga Nathan” and taught New Age-inspired meditation and mindfulness. (Once when I raised an eyebrow and asked him what that was all about he chuckled and replied, “Hey, man: it was the ’70s!”) He constantly surprised me and I was always learning something new about his life.

One thing I can say about him with absolute certainty is that Tim was brilliant. Oh boy, was he! No matter where he was or who he was with, I always had the impression that he was the smartest person in the room—not that he ever acted like he was, but watching Tim you could see him absorbing everything that was going on around him and know that his wheels were always turning. He was curious about virtually everything, could speak eloquently on a variety of subjects, and watching him crunch the numbers on the fly for his books was pretty astonishing. Tim would have project meetings at George Lucas’ Skywalker Ranch, attend holistic healing workshops at Esalen in Big Sur, talk about “radical self-expression” with Larry Harvey, the cofounder of Burning Man (and was present at the first ceremony on Baker Beach in San Francisco in 1986), lunch with Playboy’s cartoon editor Michelle Urry in Chicago, argue about all manner of nonsense at Ellison Wonderland, and consult with Tom Doherty (when he was the publisher of Ace Books) about how to construct fair contracts for creatives.

If Tim drank beer (he didn’t) he would have been a logical candidate for Dos Equis’ “most interesting man in the world” advertising campaign.

Born January 12, 1948, in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, Tim Edward Underwood grew up in Pekin, New York with his parents John and Wilma, his sister Marjorie, and his younger brother Gregory (who, tragically, was killed while camping in Alaska when a drunk fired a gun into his tent while he was sleeping). He studied for a time at Michigan State University before moving to California to become, among other things, an art and book dealer. Tim was active in Bay area fandom and regularly helped out at Charles Brown’s “Locus” collating and mailing parties; he easily formed friendships wherever he went—which often turned into professional opportunities. A chance meeting with Pennsylvania bookseller Chuck Miller [1952-2015] at a convention led to a publishing partnership in 1975.

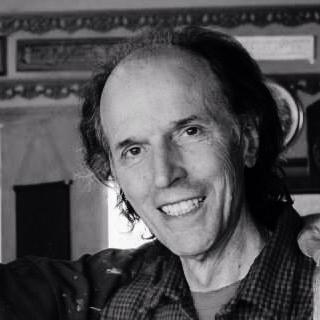

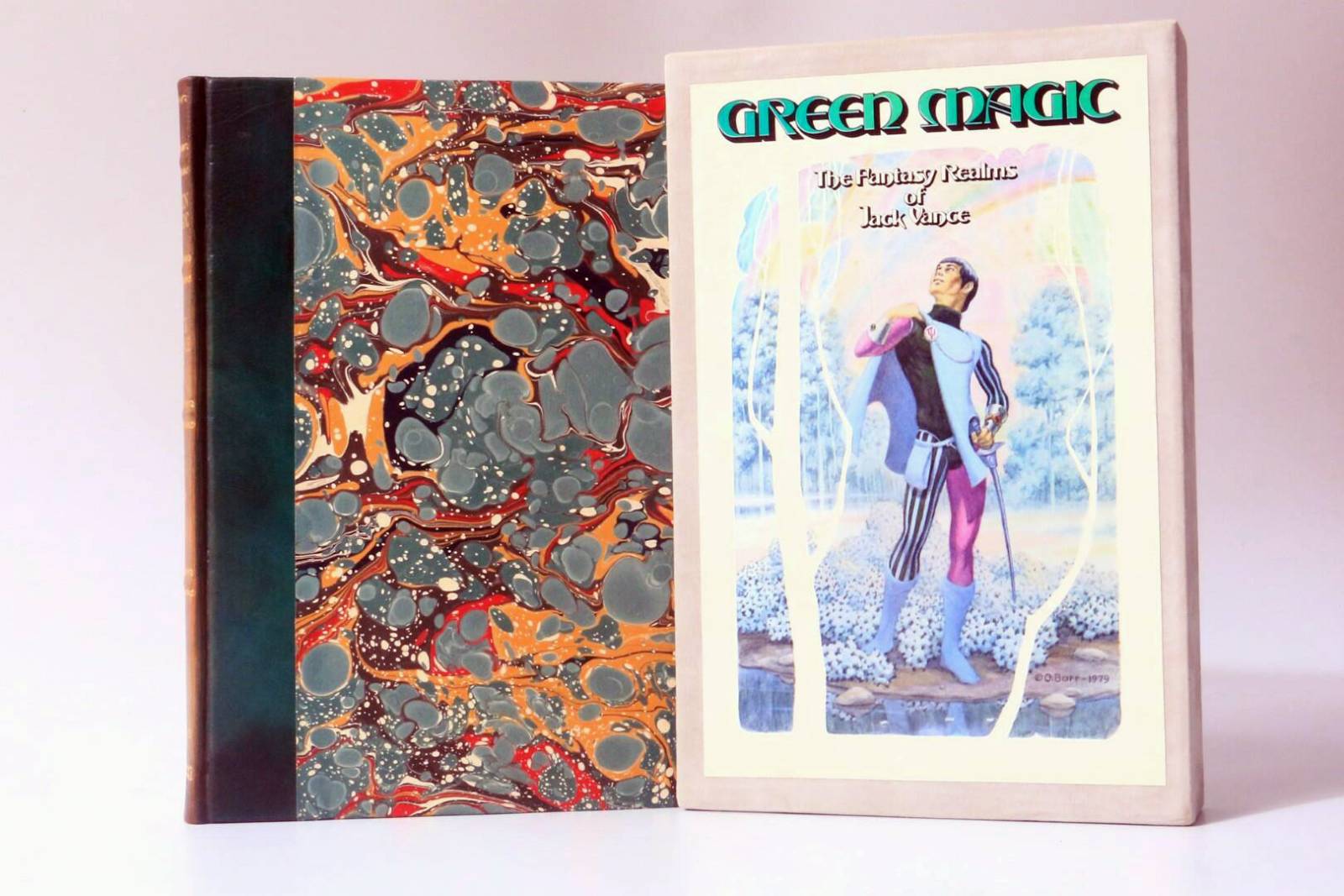

Above: Cover art by George Barr.

When “science fiction” and “fantasy” emerged as distinct genres during the pulp era independent publishers quickly emerged as well to produce inexpensive hardcover editions of novels and collections in modest editions of anywhere from 500 to 2000 copies. By the 1970s, Arkham House, Donald M. Grant, Publisher Inc., and Mirage Press dominated the SF&F small press field: Underwood/Miller upset the order of things when they appeared at the World Science Fiction in 1976 and released the first hardcover edition of Jack Vance’s “The Dying Earth” illustrated by George Barr. The other three publishers had been actively pursuing Vance, often described as one of the greatest science fiction writers of the 20th Century, for many years to secure rights to the collection without success; they grumbled and couldn’t understand how “those new guys” were able to persuade the author when they couldn’t.

The answer was simple: Jack Vance liked Tim.

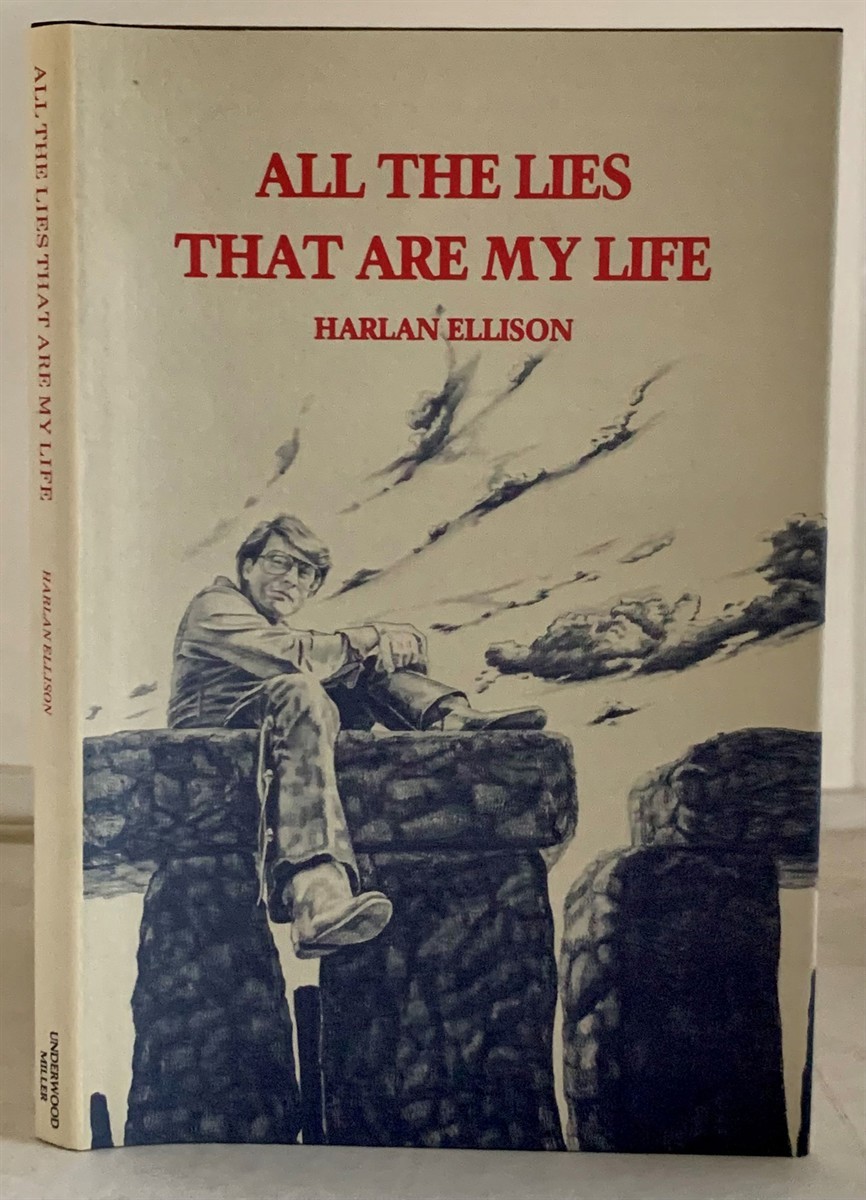

They both shared a “Bay Area Bohemian” outlook and became friends; subsequently, Underwood/Miller turned into Vance’s primary hardcover publisher, printing both classic and new works. Other writers liked Tim, too, were impressed by the high-quality of U/M’s books, and began approaching him with projects. As Chuck handled fulfillment and promotion, Tim signed deals with Philip K. Dick, Harlan Ellison, Roger Zelazny, Robert Silverberg, Stephen King, Peter Straub, and many others. But beyond the quality of their books’ contents they also raised the bar for their competitors by featuring acid-free paper, various binding materials (including leather, marbled endpapers, and hand-made wraps), a variety of title and typographic solutions, special signature/limitation pages, additional pages of content exclusive to the limited edition, slipcases and clamshell boxes: everything we’ve come to expect from a genre (and probably non-genre) deluxe edition today all largely originated with Tim Underwood’s vision and imagination.

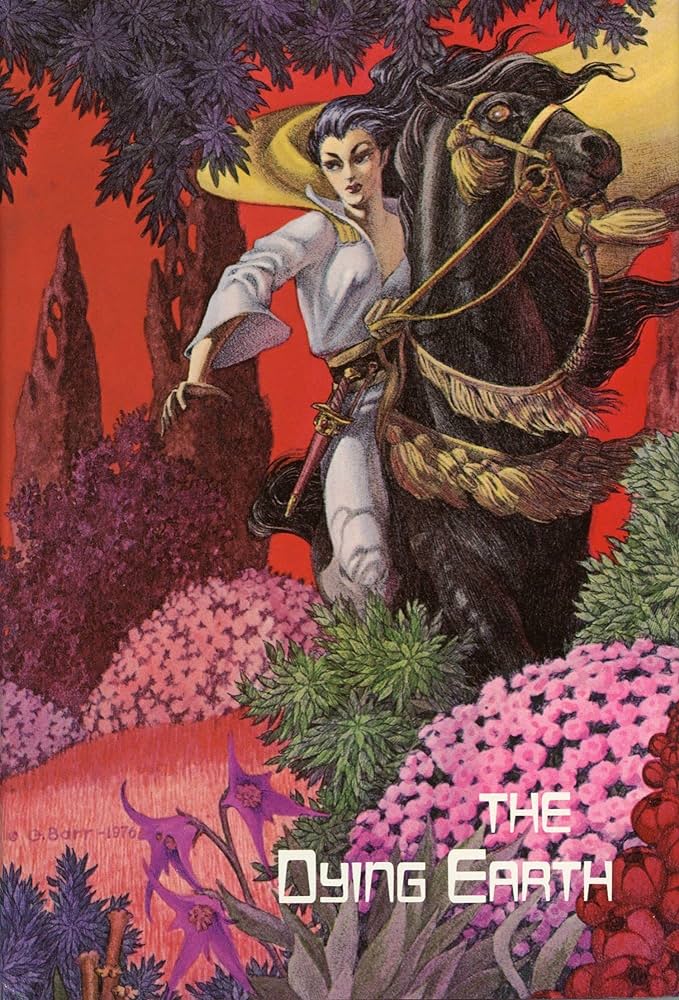

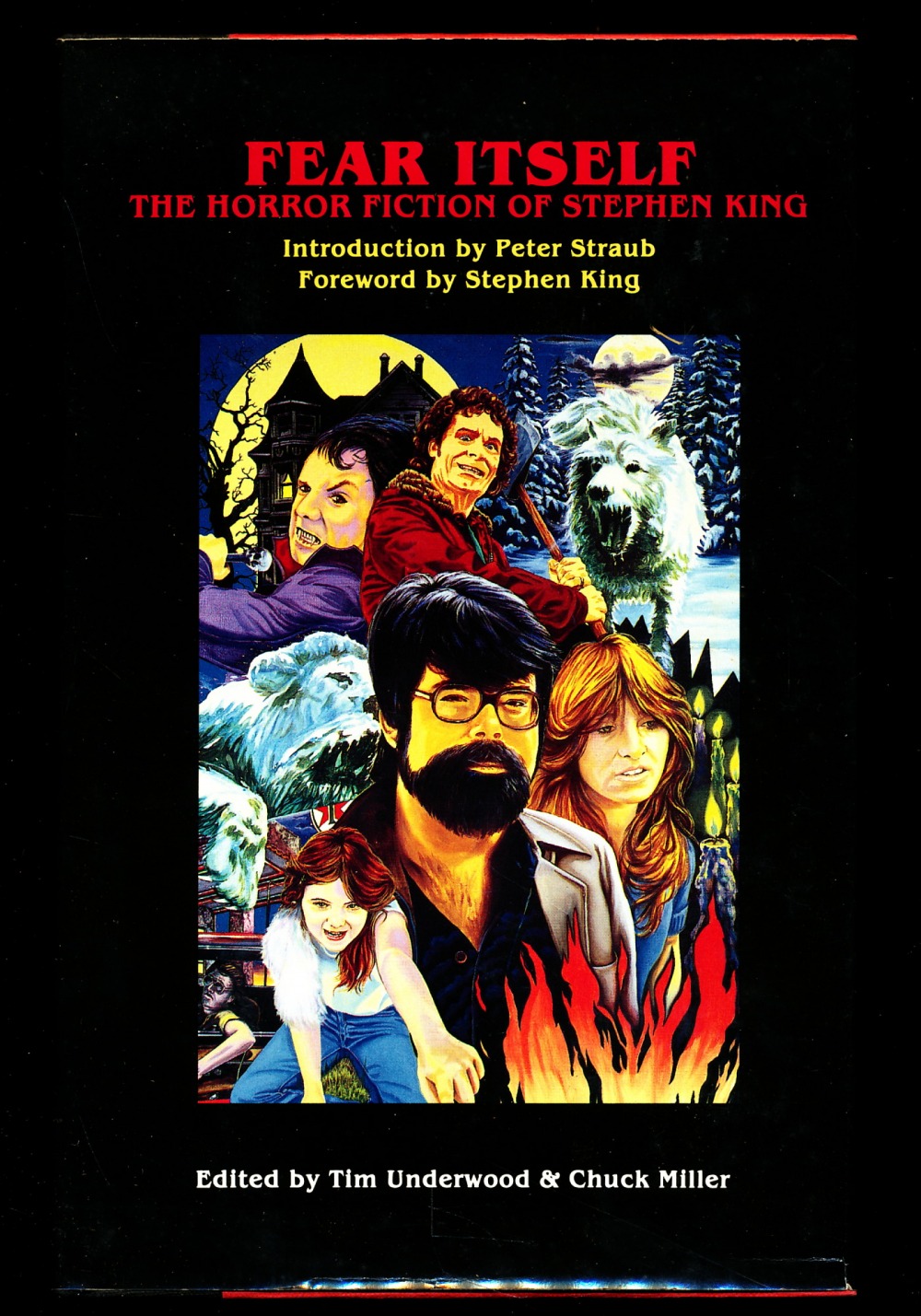

Above: Cover art by Leo and Diane Dillon.

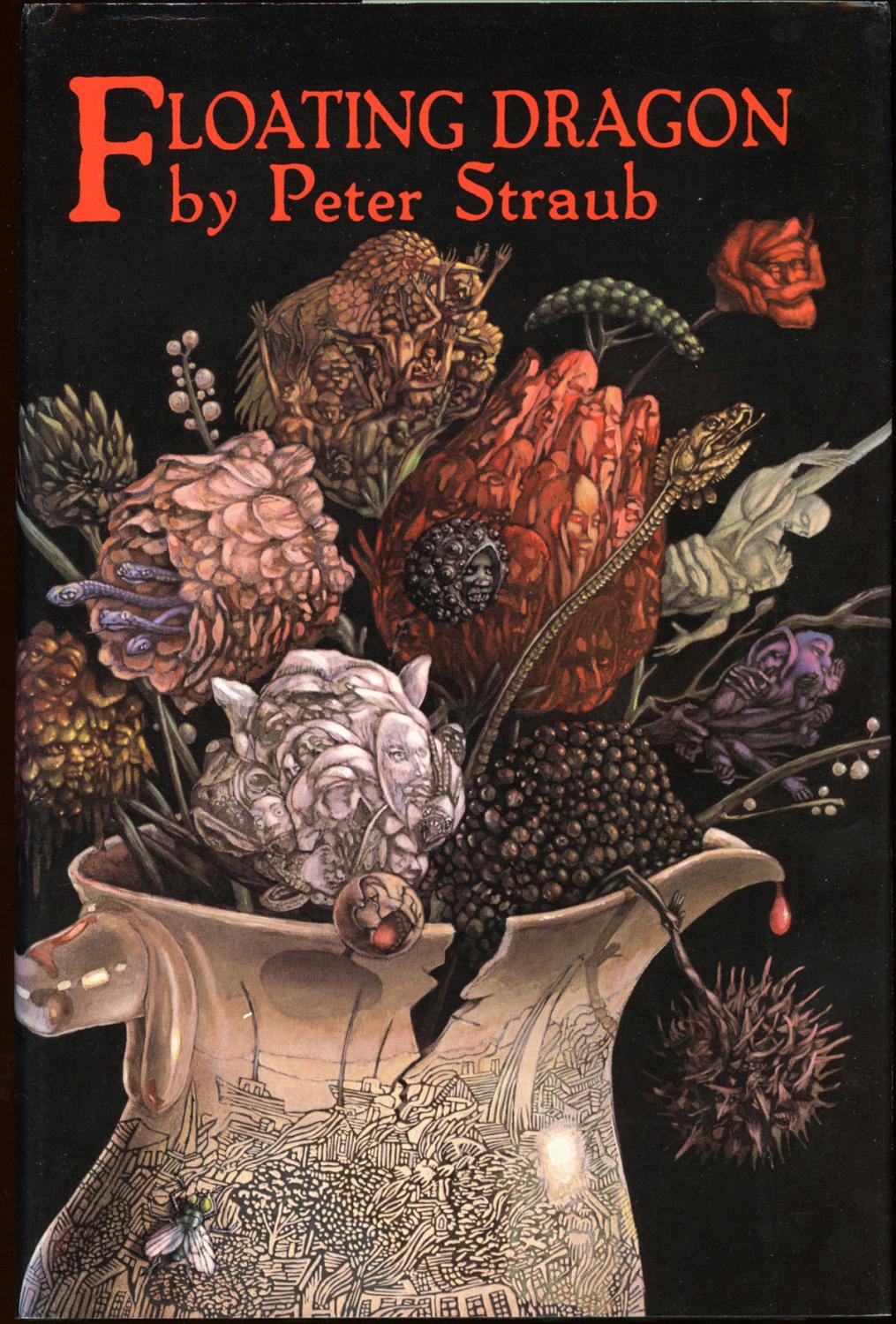

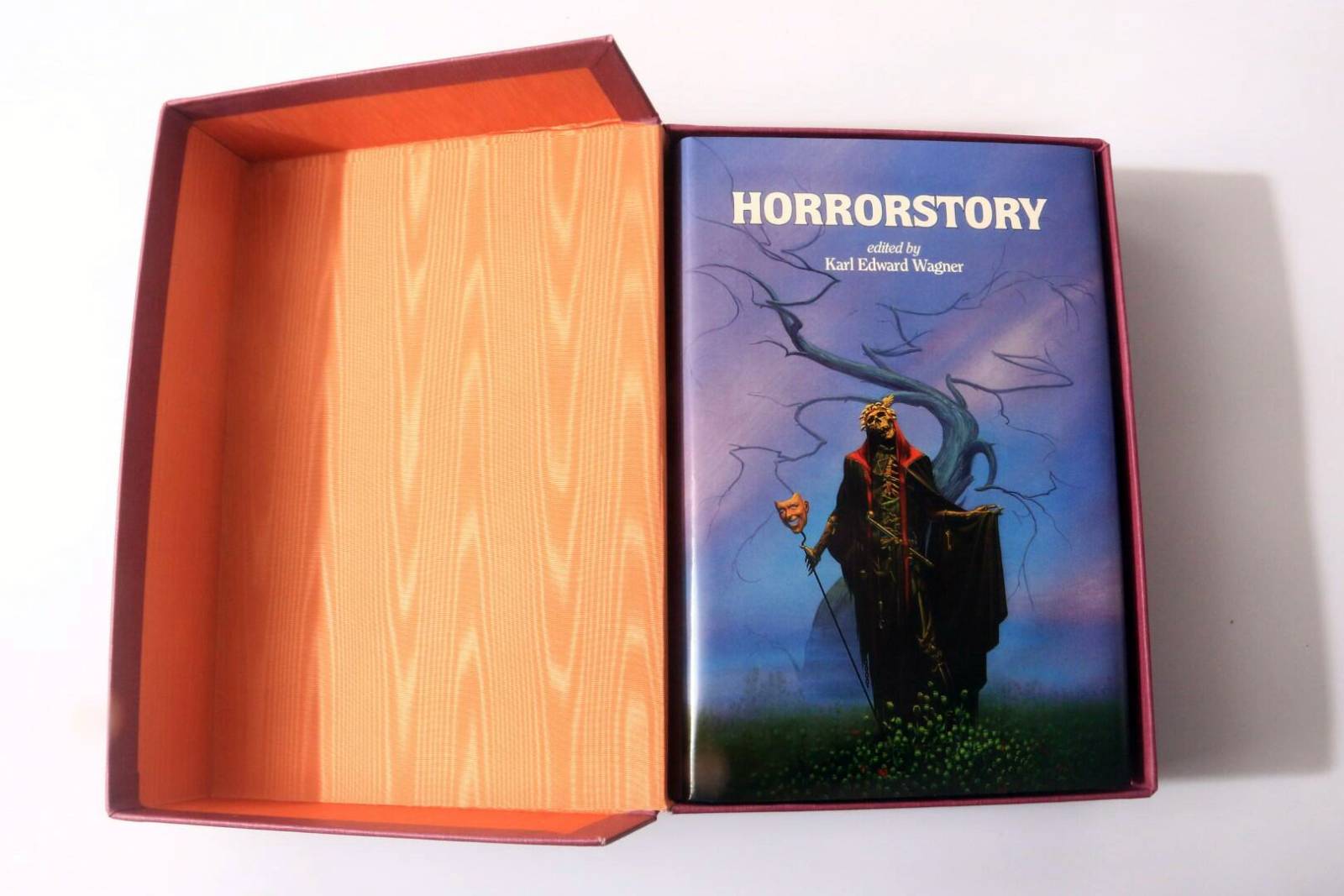

Above: Cover art by Kent Bash.

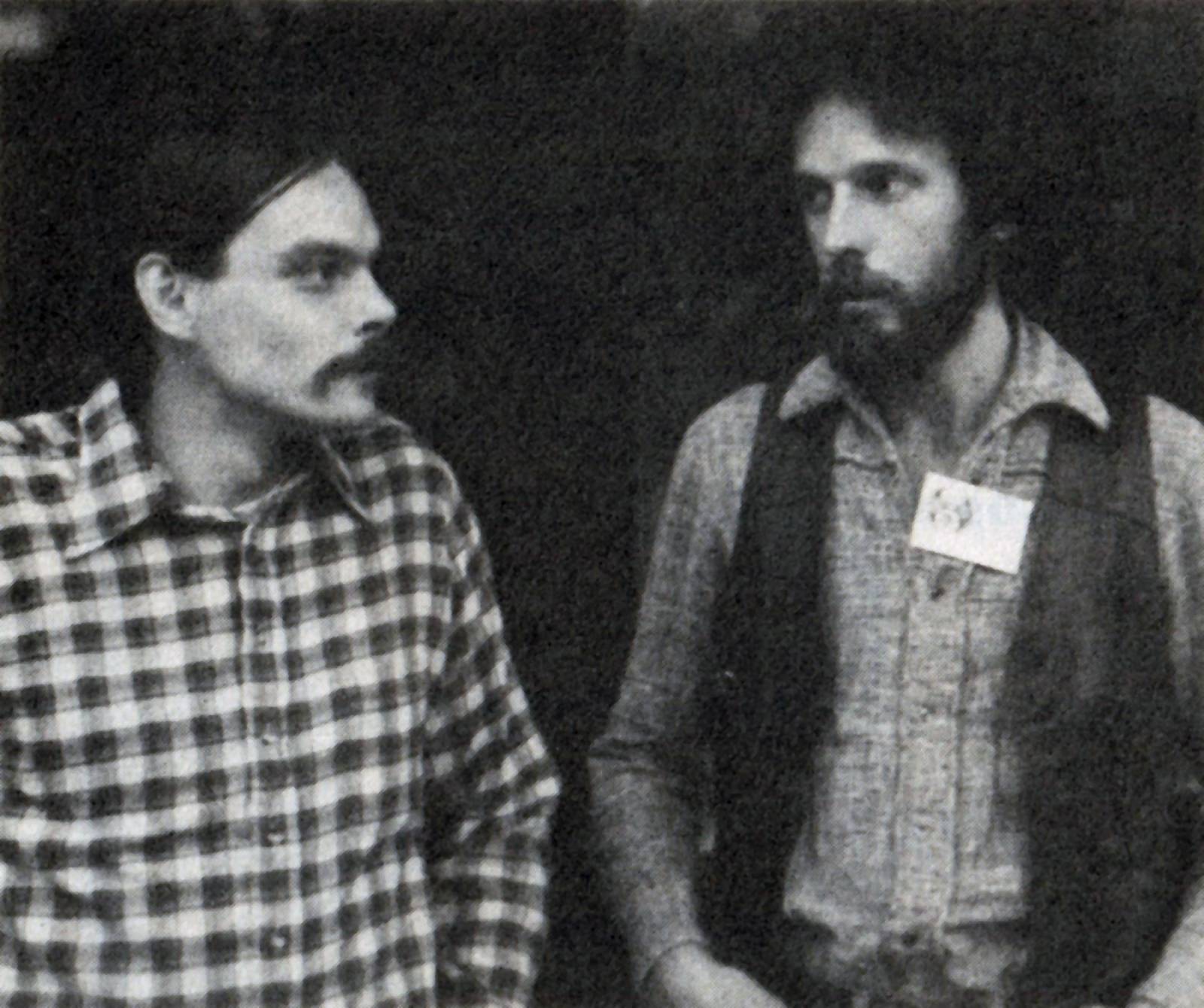

Above: Chuck Miller and Tim Underwood, circa 1978.

Above: Cover art by Kent Bash.

Above: Cover art by George Barr.

Above: Cover art by Michael R. Whelan.

Tim’s and Chuck’s reputations grew rapidly and they cochaired the World Fantasy Convention in 1980 (a sign of approval from the field’s movers and shakers), producing its first-ever hardcover souvenir book. Underwood/Miller branched out, secured professional distribution, and created additional imprints: Brandywyne Books in association with Waldenbooks, Hammersmith Books, and Third Millennium/Underwood–Miller Books. Despite their success, they eventually felt the strain of different goals and a long-distance business relationship and the two went their separate ways in 1994; that same year they were presented with the World Fantasy Award for Professional Achievement.

Tim immediately formed Underwood Books (along with a subsidiarity, Black Bart Books) and began publishing fiction, pop culture, self-help, and art titles; he produced books about Led Zeppelin, R.E.M., and Bob Dylan, multiple volumes collecting the letters of Philip K. Dick, and what I believe were the first mass-market explorations of ADD and ADHD.

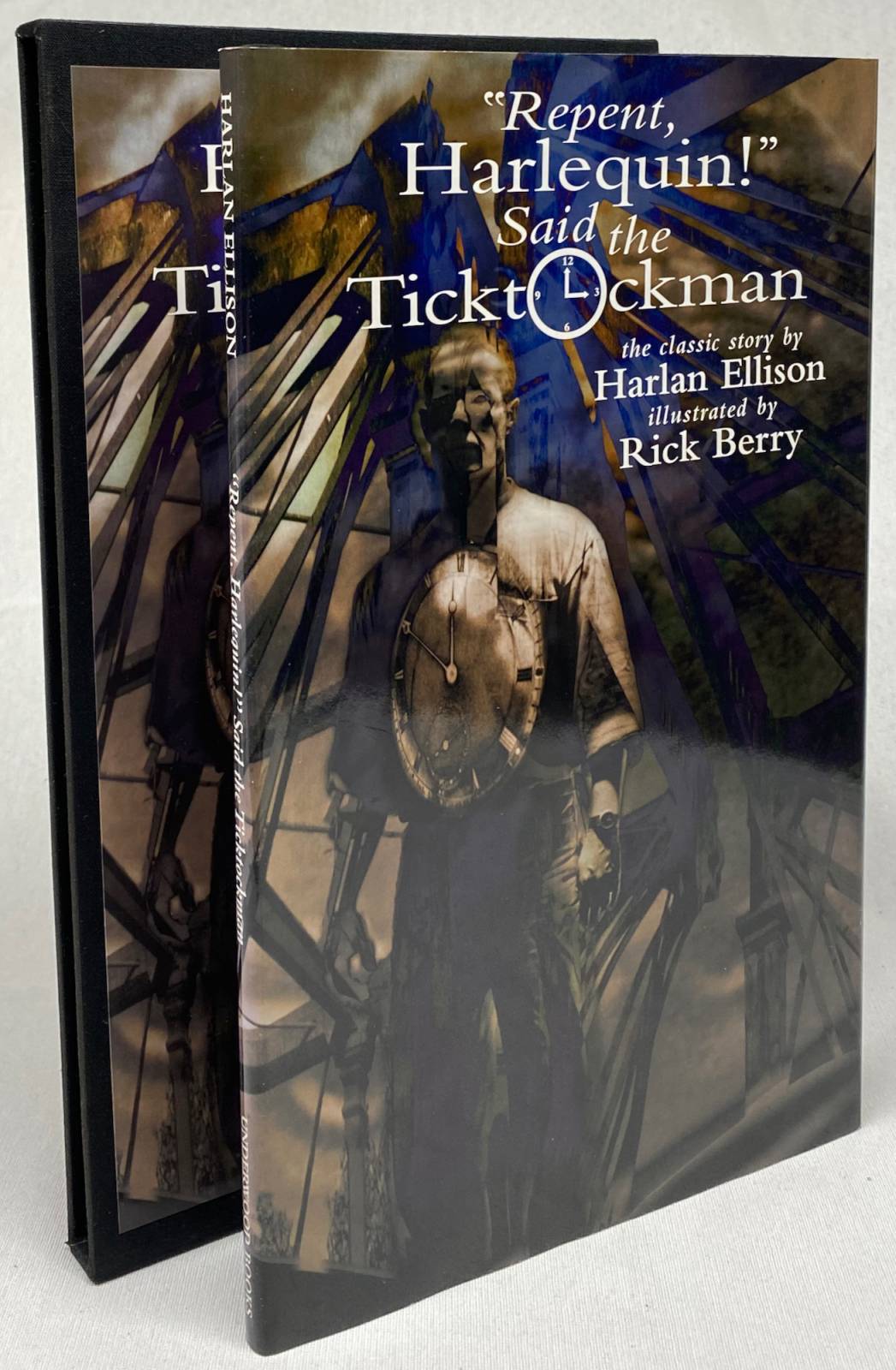

Above: Cover art by Rick Berry.

And, of course, there were the gorgeous art books. Tim was always a huge illustration fan and had produced volumes devoted to Hannes Bok, Bernie Wrightson, Virgil Finlay, and Don Maitz while part of U/M so it was only natural that he would continue with his new imprint—and that’s where our paths intersected.

I had met Tim at that previously-mentioned 1976 World Con in Kansas City—I still have my copy of “The Dying Earth”—and over the years we slowly built a friendship. While working at Hallmark I had also been a freelance art director and illustrator for various publishers in the late 1980s and early ’90s; there were a million freelancers much more talented than I was but for some reason Tim liked what I was doing and asked me to design some covers and, eventually, a new logo for him, which I was delighted to do. Cathy and I were never partners in Underwood Books, just freelancers, yet we had an extremely close working relationship and we did a whole lot of stuff together. Each project led to another and another and another until we were talking on the phone one night and I was lamenting how I had been pitching the idea of a “fantastic art annual” for ten years and couldn’t get a publisher interested. Without skipping a beat Tim said, “I’ll do it.”

And “Spectrum: The Best in Contemporary Art” began.

Above: Cover art by James Gurney.

It may have been my and Cathy’s idea, we may have put it together and done the heavy lifting up front, but it was Tim’s belief, optimism, and drive that made it a success. Spectrum not only became Underwood Books’ flagship title for twenty years (until we retired and licensed it to John Fleskes), but also became an international symbol of quality, diversity, and respect for our field.

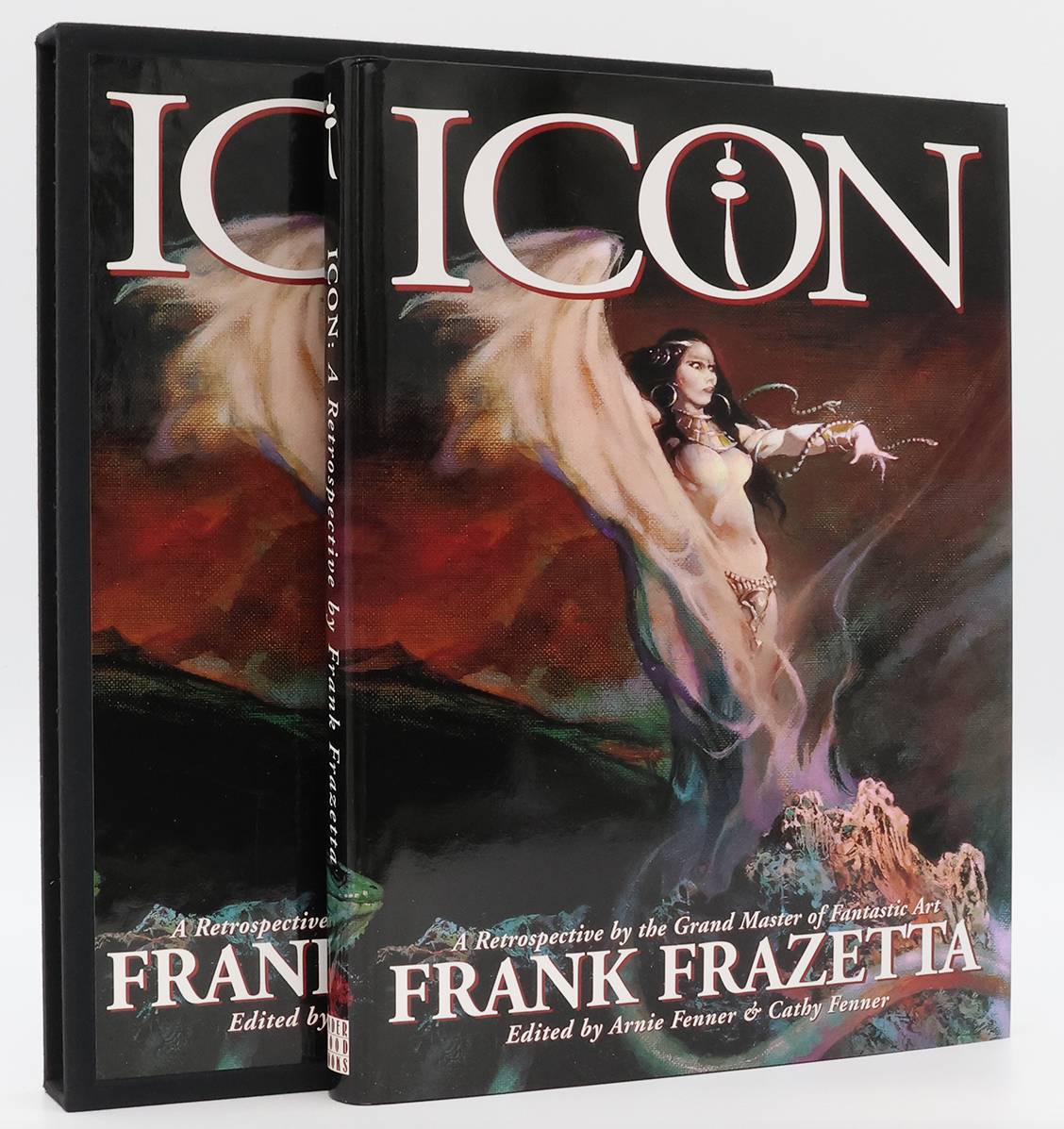

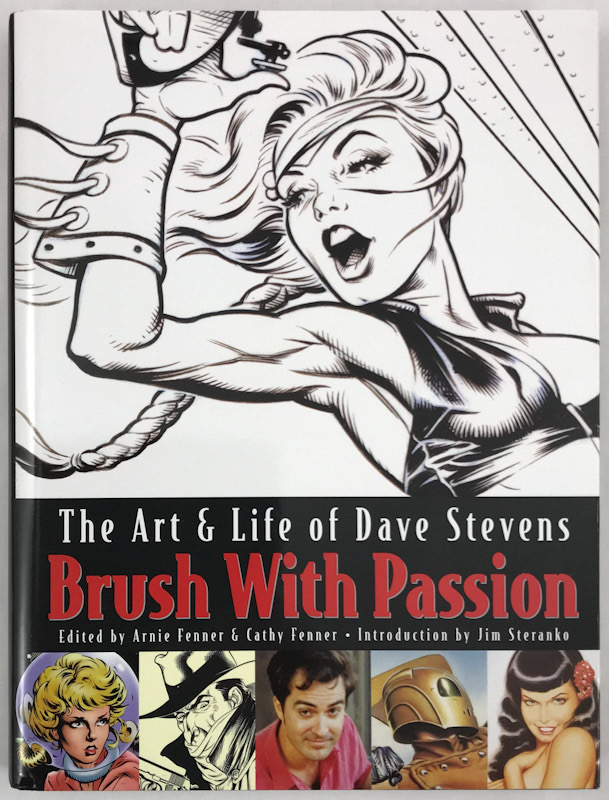

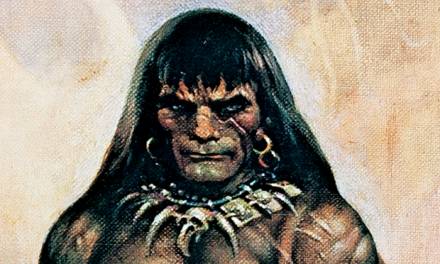

Other major art books followed by John Jude Palencar, Jon Foster, Robert E. McGinnis, Jeffrey Jones, Gahan Wilson, Dave Stevens, Donato Giancola, Frank Frazetta, and many others. Some were successful, others not, but they were all beautiful either way. He turned down many projects that I thought could have been very lucrative and grown his business; when I’d encourage him to expand, get an office, and hire a few people he’d just laugh and say, “Naw, man, being small is good.”

But Tim was more than just a publisher of art books, he was also a benefactor, a patron, a promoter, and, above all a compassionate friend of those he worked with. He greatly expanded Wrightson’s audience well beyond comics long before every store had a graphic novel section; the trilogy of Frazetta books brought the artist back into the spotlight after his nearly being forgotten by the mass-market for over a decade (while Frank’s wife, Ellie, used the advances and royalties to build the Frazetta Museum in Pennsylvania); he supported Virgil Finlay’s daughter, Lail, with advances for projects that he most likely knew would never be done; he came to Jeffrey Catherine Jones’ rescue when she was arrested for DWI and paid her bail (and turned a blind eye when Jeff sold an art book to another publisher even though she was under contract to—and had received an advance from—Tim for a third collection); and he provided financial support to Dave Stevens near the end of his life as he battled leukemia.

Above: Cover art by Frank Frazetta.

Above: Cover art by Dave Stevens.

Tim Underwood was someone who quietly, steadily, without much credit or recognition, worked behind the scenes to make things happen for creators, to lift them up, and in doing so opened doors of opportunity for them that might otherwise have remained closed. As John Jude Palencar wrote me upon learning of Tim’s passing, “His generosity, kindness and support of so many artists was beyond compare. Not only did he publish my art book but you could sense a greater mission and his thoughtfulness to the community of artists worldwide. The Spectrum annuals will forever be part of his wonderful and enduring legacy. Many artists owe him thanks for furthering their careers.”

Tim Underwood was a mensch.

He had his share of frustrations and disappointments, to be sure: that’s the nature of publishing. There were people who pocketed advances then disappeared without delivering anything, licensors who had inexplicable melt-downs and canceled projects that were in the works (and, you guessed it, kept the advances), and he was forced to contend with a handful of spurious lawsuits (all of which he won or settled to his satisfaction) even while he was dealing with his health problems. Tim, like virtually every small publisher, was never wealthy and took serious financial hits when Borders, B. Dalton’s, Brentano’s, and Waldenbooks—all major clients—went bankrupt owing him a lot of money that he never recovered; several years later the same thing happened again when his distributor, Publishers Group West, went bankrupt and was acquired by the Perseus Book Group, paying him only a small fraction of what he was due.

But through it all, the good times and the bad, Tim remained upbeat, found a way to pay the bills, tried to help others, and always looked to the future. “Tim abides.”

Above: Tim and friends show off their mandalas.

After we retired he seriously cut back his activities, too, happily spending his days gardening, tending his fruit trees, reading to his young daughter Grace, and studying (and creating) mandalas. Tim eventually sold his property in Nevada City (which we jokingly called Camp Underwood), sold his letters, art, and the file copies of his books, married Grace’s mother, Rebecca Bowler, and moved to a Bay area apartment to be closer to them. When we started doing the Spectrum bookazine I added the Underwood Books logo to the bacover next to ours even though he wasn’t involved because, shoot…Underwood and Spectrum were part of the same story and Cathy and I wanted to symbolically acknowledge his importance and ongoing influence.

We’d talk on the phone about projects he might still want to do—he had a Tolkien reference in mind as well as a definitive Virgil Finlay collection and possibly a final volume of Spectrum under our editorship—but it soon became obvious that time wasn’t going to allow it. He had been privately and bravely combatting melanoma for well over a decade and had undergone multiple surgeries and treatments through the years; regardless, Tim was a perpetual optimist and, as he did with virtually everything he focused on during his lifetime, became an expert about the disease and possible solutions. But in recent months his cancer became more aggressive and on October 11, 2023, Tim lost his fight and the world became a little dimmer.

Yeah, we had our disagreements—who wouldn’t over 47 years?—yeah, we argued sometimes, yeah, there were times when he was pissed at us and we at him—but it never changed the way we felt about each other. Tim was much more than Cathy’s and my friend: he was our brother, through thick and thin, always there to listen, always there to help, and he’ll never be forgotten.

He is survived by his wife Rebecca Bowler, daughter Grace Underwood Bowler, children from his first marriage (to Deborah Pollman), Mollie Underwood (Jae) and Dylan Underwood, and his sister Marjorie Underwood Godersky.

Wherever he is we take comfort in knowing that “Tim abides.” With any luck, we can all hope that we do, too.

I’m sorry for your loss and all of ours. This made me smile and chocked me up all at once.

Tim’s impact on the world of publishing and the lives of those around him is truly remarkable. His generosity,

vision, and unwavering support for artists and writers will continue to resonate for years to come. A true pioneer in every sense of the word. “Tim abides” is the perfect tribute to such a unique and inspiring soul. Rest in peace, Tim. You will never be forgotten.