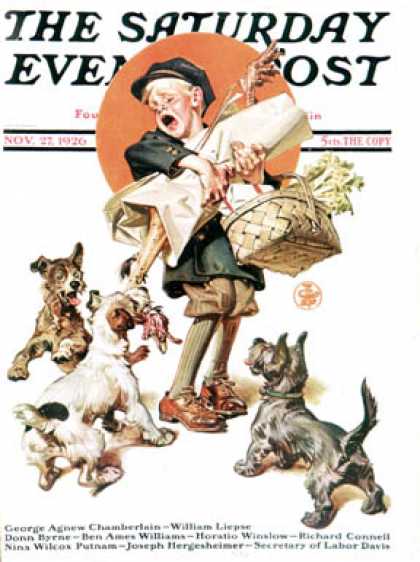

It was a long time before I got comfortable with a painting not living up to the idea or picture in my head. It took a lot of training or ‘dirt time,’ as we used to call it, to get even close to matching my initial idea in pigment. There was a lot to learn and experience.

But eventually the two started to get much closer, and this allowed me to understand not only that I was getting better, but how I was getting better. I used it to measure my skills. The closer it was to the image in my thoughts, the more confidence I built to be able to capture whatever image I wanted. But it still wasn’t exact.

That’s because the real reason is far richer than I expected.

I’ve researched a lot of neuroscience and I’m curious how the brain works. The latest findings are amazing and challenges all we knew about the brain and most importantly, how we learn.

That picture in your head is not just visual. It’s a combination of memories and senses from across the brain.

The brain doesn’t think or calculate like a computer. In recalling a memory, functioning MRI scans (fMRI—real-time scans) have found that the mind accesses multiple memories in multiple areas of the brain to re-build a thought. It might gather information from olfactory, tactile, or audio memories. That picture in your head is not just visual. It’s a combination of memories and senses from across the brain. I find this fascinating.

The brain is capable of not only looking at several angles of depth at one time, but also moments in time. It’s difficult to capture a single moment for a painting idea because the brain is examining multiple moments at one time and giving you that memory as if it’s a single moment.

That’s one reason why our painted pictures might not match the pictures in our head: our mental image is always changing, ever so slightly, even though it feels like the same idea. This makes it important to use the picture in your head as a guide for your finished piece and not as a blueprint.

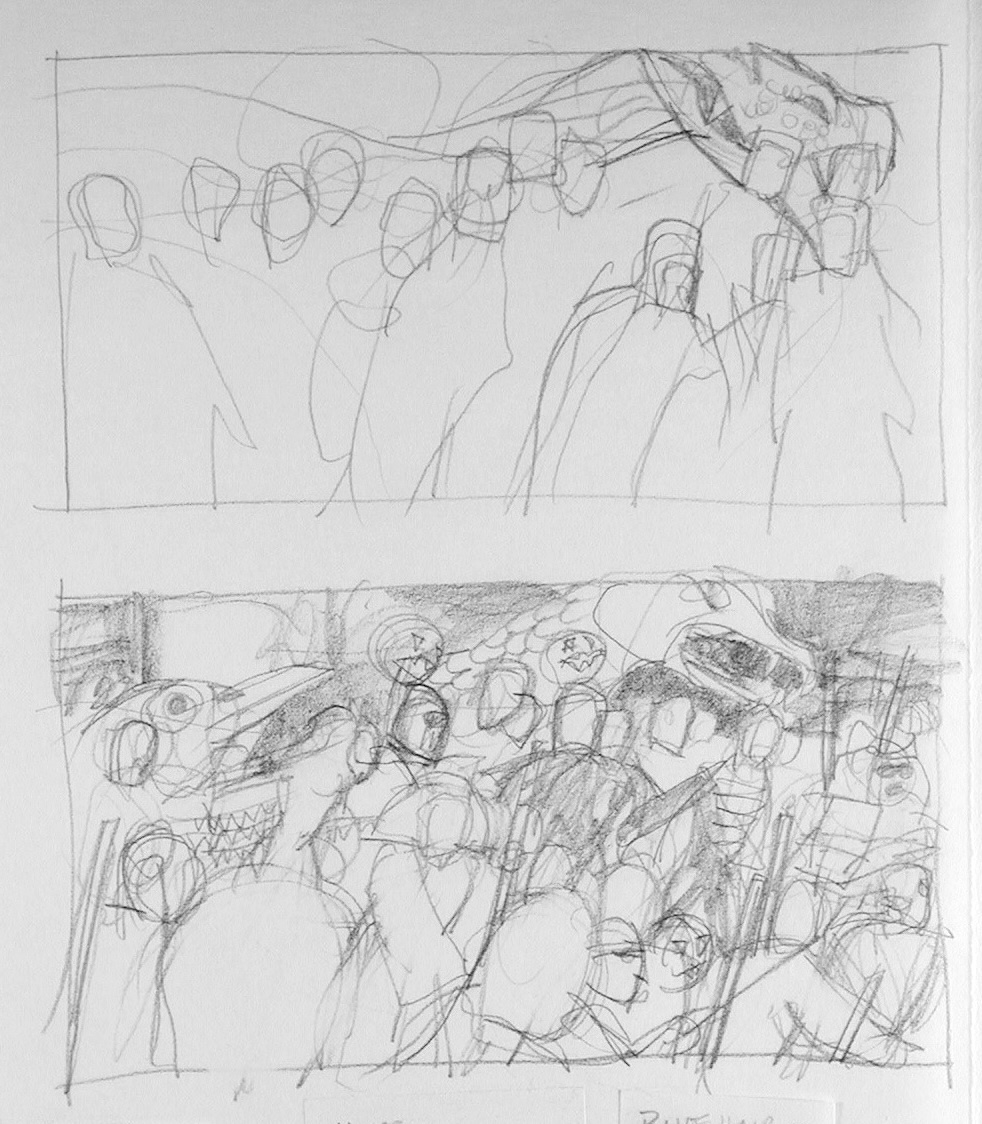

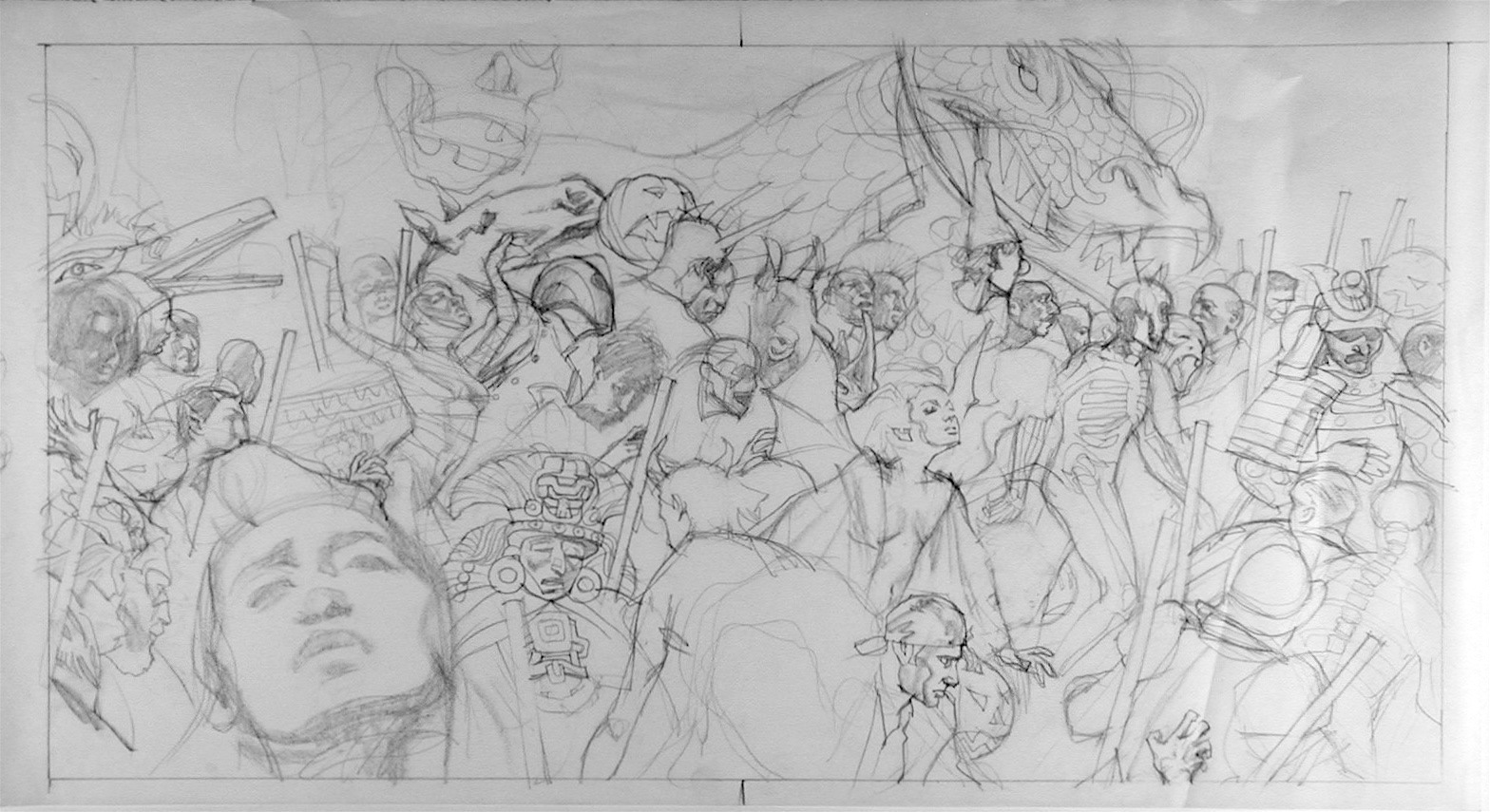

It’s important to build the design of a painting from multiple thumbnails first in order to capture as much of the idea on paper as you can. That’s why it’s critical to understand good composition. Your brain isn’t restricted by compositional limits. But the actual painting is. So once the design is drawn out, you can use the image in your head to help manipulate the real piece of art. Probably the opposite of what you might’ve been experiencing.

I still “refer” to my mental image when I paint an idea because that image feels accurate to my desire. The thumbnail is the link to that memory and the two work together to pull your image together.

Once I saw how that worked, I relaxed and was able to follow the energy of my painting more than before. I understood why the idea doesn’t need to fit like a puzzle piece.

With this approach in mind, see if you can learn faster and work with your brain and your painting in tandem instead of at odds.

This is such an interesting and eye-opening explanation!

It can be so frustrating trying to reproduce the image in one’s head, until one realises that exact image is also constantly in flux … like a dream. Capturing it 1:1 is a fool’s errand, like trying to hold sand.

Thank you for this article!

ʜᴏᴍᴇ ᴄᴀꜱʜ ᴇᴀʀɴɪɴɢ ᴊᴏʙ ᴛᴏ ᴇᴀʀɴꜱ ᴍᴏʀᴇ ᴛʜᴀɴ $500 ᴘᴇʀ ᴅᴀʏ. ɢᴇᴛᴛɪɴɢ ᴘᴀɪᴅ ᴡᴇᴇᴋʟʏ ᴍᴏʀᴇ ᴛʜᴀɴ $4.5ᴋ ᴏʀ ᴍᴏʀᴇ ꜱɪᴍᴘʟʏ ᴅᴏɪɴɢ ᴇᴀꜱʏ ᴡᴏʀᴋ ᴏɴʟɪɴᴇ. ɴᴏ ꜱᴘᴇᴄɪᴀʟ ꜱᴋɪʟʟꜱ ʀᴇQᴜɪʀᴇᴅ ꜰᴏʀ ᴛʜɪꜱ ᴊᴏʙ ᴀɴᴅ ʀᴇɢᴜʟᴀʀ ᴇᴀʀɴɪɴɢ ꜰʀᴏᴍ ᴛʜɪꜱ ᴀʀᴇ ᴊᴜꜱᴛ ᴀᴡᴇꜱᴏᴍᴇ. ᴀʟʟ ʏᴏᴜ ɴᴇᴇᴅ ɪꜱ 2 ʜʀꜱ ᴀ ᴅᴀʏ ꜰᴏʀ ᴛʜɪꜱ ᴊᴏʙ ᴀɴᴅ ᴇᴀʀɴɪɴɢ ᴀʀᴇ ᴀᴡᴇꜱᴏᴍᴇ. ᴇᴠᴇʀʏ ᴘᴇʀꜱᴏɴ ᴄᴀɴ ɢᴇᴛ ᴛʜɪꜱ ʙʏ ꜰᴏʟʟᴏᴡ ᴅᴇᴛᴀɪʟꜱ ʜᴇʀᴇ.

.

ᴍᴏʀᴇ ᴅᴇᴛᴀɪʟꜱ ꜰᴏʀ ᴜꜱ —————➤ Cash43.Com

This is such a relief to learn. It’s good to know I can stop chasing “the image in my head” because it’ll never happen. Thanks Greg!

Real on the web h0me based work to make more than $14k. Last month I made $15738 from this home job. Very simple and easy to do and procuring from this are just awesome . For more detail

visit the given interface————➤ Www.Salary7.Zone

HLO

i get paid $550+ per day using my mobile in my part time. Last month i got my 4th paycheck of $17723 and i just do this work in my part time. its an easy and awesome home based job.

Anybody can do this…….. Www.Worksprofit1.online

Its always nice to see other people talking about this. This topic constantly comes up in my livestream community- the idea of drawing what’s in your head i so often seen as the ultimate goal for young artists.

I like to use an example of imagining an eerie haunted house. where it might have context and history that makes it feel creepy; maybe a murder happened there. There might be creaking noises, or random cold breezes that give you goosebumps, none of which is visual, yet when you imagine it you can still oftentimes feel the eeriness.

Which is why the goal is oftentimes to communicate the mood/idea rather than accurately depict what we “see” in our head. Otherwise it might just look like an old house, but not convey hauntedness.

This is fascinating! Thanks Greg!

These are 2 pay checks $78367 and $87367. that i received in last 2 months.I am very happy that i can make thousands in my part time and now i am enjoying my life.Everybody can do this and earn lots of dollars from home in very short time period.Just visit this website now… . Www.Homeprofit1.site

Hi Greg! I’m curious if you’d be open to sharing the resources you found. I’ve been working on an article slowly in the background about how our brains work visually (and otherwise) as artists, and its effect on our artwork. I have aphantasia, and it seems an unusually-high percentage of artists do, and it raises some interesting questions as to how our brains intake, transform, store, and then regurgitate ideas visually. The one thing that’s been tripping me up is finding the science side of the discussion, so I’d love to read into what you’ve seen!

ꜱᴜᴘᴇʀ-ꜰᴀꜱᴛ ᴍᴏɴᴇʏ-ᴍᴀᴋɪɴɢ ᴏɴʟɪɴᴇ ᴊᴏʙ ᴛʜᴀᴛ ꜰʟᴏᴏᴅꜱ ʏᴏᴜʀ ʙᴀɴᴋ ᴀᴄᴄᴏᴜɴᴛ ᴡɪᴛʜ ᴄᴀꜱʜ ᴇᴠᴇʀʏ ᴡᴇᴇᴋ. ʙʏ ᴡᴏʀᴋɪɴɢ ᴊᴜꜱᴛ 2 ʜᴏᴜʀꜱ ᴀ ᴅᴀʏ ᴀꜰᴛᴇʀ ᴄᴏʟʟᴇɢᴇ, ɪ ᴍᴀᴅᴇ $17,529 ʟᴀꜱᴛ ᴍᴏɴᴛʜ. ɪ ʜᴀᴅ ᴢᴇʀᴏ ᴇxᴘᴇʀɪᴇɴᴄᴇ ᴡʜᴇɴ ɪ ꜱᴛᴀʀᴛᴇᴅ, ᴀɴᴅ ɪɴ ᴍʏ ꜰɪʀꜱᴛ ᴍᴏɴᴛʜ, ɪ ᴇᴀꜱɪʟʏ ᴇᴀʀɴᴇᴅ $11,854. ᴛʜɪꜱ ᴊᴏʙ ɪꜱ ɪɴᴄʀᴇᴅɪʙʟʏ ᴇᴀꜱʏ ᴛᴏ ᴅᴏ, ᴀɴᴅ ᴛʜᴇ ʀᴇɢᴜʟᴀʀ ɪɴᴄᴏᴍᴇ ɪꜱ ꜰᴀɴᴛᴀꜱᴛɪᴄ. ᴡᴀɴᴛ ᴛᴏ ᴊᴏɪɴ ʀɪɢʜᴛ ɴᴏᴡ? ᴊᴜꜱᴛ ᴠɪꜱɪᴛ ᴛʜɪꜱ ᴡᴇʙᴘᴀɢᴇ ꜰᴏʀ ᴍᴏʀᴇ ɪɴꜰᴏ.

ᴍᴏʀᴇ ᴅᴇᴛᴀɪʟꜱ ꜰᴏʀ ᴜꜱ ———-➤ HighProfit1.Com