The early years of an artist’s development are often spent hammering out basic foundation skills. These will serve as the core of all that they create. During this time, the artist should not be terribly preoccupied with questions of style, vision, direction, brand, etc. We have to stand before we walk and bypassing the basics rarely does anybody any good in the long term. Of course, it’s the style and vision of other artists which inspired most of us to become artists in the first place, so the temptation to follow in those footsteps (with or without doing the necessary prep work) is always lingering. I feel it’s because of this that artists, developing artists in particular, look for a voice by imitating the voices of others. To what degree this is done varies, but I’m certain we‘ve all done it. In the beginning, we admire the work of our idols and in some way wish to emulate that work, just as they did with their own idols. We strive to accomplish what our heroes have accomplished and to follow their aesthetic footsteps. Now, there is no doubt that much can be learned from our heroes and peers, but at some point every artist must put the imitation aside and find their own path. Otherwise, you become a clone. It is the failure to move past one’s key influences that results in clones, and the clone is always inferior to the original because they are content to imitate rather than risking to innovate.

Ultimately, I feel it is the goal of the artist to create what has not been created before. As an illustrator, it is also in your best interest to cultivate a compelling and unique aesthetic which separates you from the herd. These are both tremendously daunting tasks, which is exactly what makes them important. Only the very best will achieve these goals (though if the first is truly achievable is up for debate) though simply attempting them makes us all better.

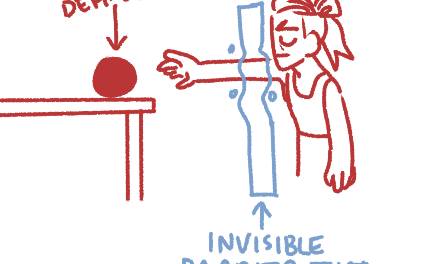

Among the most frequently asked questions of the aspiring visual artist, I would expect to find “how do I develop my style” near the top of the list. The answer I typically give is to not worry about finding your style because once you’ve mastered the fundamentals of drawing, light and shadow, perspective, color, anatomy, and/or any number of other technical skills required, your style has more than likely found you. Style is nothing more than the sum of your intentions and you limitations. You have a vision and execute it to the best of your ability. Once your skill is at a high enough level to yield consistently satisfying results, you will be producing work with a consistent and recognizable style to it. This is because you are always pitting what you want to create against what you are able to create and style is where the two meet. Over time you reinforce your habits and learn to control your weaknesses so that they all cooperate and result in something uniquely “you”. You could also look at style as the specific points in which one’s images depart from “reality“, however I still feel those are the direct result of your intent and shortcomings uniting. Regardless of one’s level of skill, some aspects will forever be outside our control. When young artists wish to jump the line and adopt the style of more experienced artists, they are really only imitating that artist’s shortcomings mingled with creative choices which they may or may not fully understand.

In developing our abilities as artists (and in turn our individual style), the side of this which we pay the most attention to is developing skill to limit our flaws. This is fairly academic work and quite left-brained, made up primarily of repetitive practice and study of whatever subjects we are lacking in. It’s tremendously important, but not tremendously exciting. Oh sure, the idea of it might be attractive because of the potential reward, but the execution is long, slow, and trying. The other side of the style coin, however, is our intent. What we mean to do with our skill. This is often made up from the influence of other artists and it is what drives us to improve just as it inspired us to begin. This side is very right-brained. It’s made up of creative thought, problem solving, and a desire to communicate. Any artist of quality must train both of these areas. You need to know how to speak and also have something interesting to say.

The artist lacking in technical ability often overestimates the value of their creative ideas. A painter not yet capable of successfully translating those ideas into images can’t advance them or improve them. For this reason, the focus is placed first on developing those technical abilities and this is wise because it’s a long and difficult process. Somewhere along the road, however, one has to begin consciously developing their creative intent as well. When and in what balance I don’t know, but at some point it becomes necessary. As I’ve said, most of us begin with imitation. This is the starting point and I feel it stays with us longer than we realize. It hangs out in the back of our minds so long that we don’t notice it anymore. As our skill muscle grows, we will naturally begin to branch out and begin stirring our intent muscles. We become exposed to new ideas which filter in to our intent. It is totally possible to develop a fairly independent style through natural evolution and progression. Left alone without conscious improvement, however, this can stagnate. I feel this (even more than perceived market demand) is why there is so much sameness in genre illustration. Not amongst those leading the field, but for those trying to break in or struggling to keep up. Left alone, the intent muscle is still focused on creating what has already been created in ways which have already been done time and time again. That said, I do feel that one can and should guide their own style by following the stars of others.

One can hardly blame an artist for aping their predecessors. Being the spark that set us in motion, the last thing which I’d suggest is to shut out, suppress, or ignore your influences. They are beacons helping to point you towards your own path. What I propose instead is to begin looking at your influences from a new direction. For most of our lives, we’ve focused our attention on what it was that our idols did which excited and inspired us. Now it’s time to look at where they fall short. This is the opportunity for us to elevate ourselves. This is the way which we will find our vision: that elusive unique aesthetic which we struggle towards. We probably don’t yet know exactly what it is, not really, but deep down we have an inkling and ultimately wish to bring it into the light. An artist may spend their entire life chasing it, trying to realize it and know it. This chase is what I feel drives innovators and exceptional creators forward.

I propose this exercise to help in finding your vision: Choose a handful of artists which you feel the most excited and inspired by. The ones who’s general body of work resonates strongest as the pieces you wish you had made. Think about what makes these artists unique and strong. Look at what is similar between them. Remember why you love them. So far this is essentially the same as gathering an influence map, but the next bit is where things can get interesting. Now, one by one, find where your influences are lacking. This is not to say find where they have failed, because you’re not necessarily looking for errors or technical weakness. Rather, find where they have made creative and technical choices which do not quite satisfy you. Think about what you would have rather they had done instead. Where did they go too far? Where did they not go far enough? What is it that is missing? Don’t be afraid to nitpick. Now look at your own work and ask yourself: are you supplying the missing elements? This is not arrogance, but rather a way of using their work as a mirror to compare our own. It also means acknowledging that our goals may not be (and in fact almost certainly are not) identical to those of our heroes. The choices they made were their choices, so we quite likely do not agree with all of them. Looking beyond your admiration and focusing on what could make your favorite art even better to you will help bring your own vision that much closer to the surface. Then, when you are working on your next piece, ask yourself: how well is this satisfying my vision? In what ways can I improve that?

Fantastic piece David- Thanks! I especially like the last paragraph. I think if we can learn to be constructively critical of our influences we can do the same with our own art without the emotional filter that went into making it. Art is definitely not for pussies;)

P.S.- Beautiful Painting!

Encyclopaedic. Wow.

So good, so important. Well done.

My style ran away, still can't find it. Looked everywhere. Really good Dave even the second time.

Direction and artistic voice happens to be a topic of discussion in my head as of late. I spoke with a gallery owner recently and he loves my work but asked “Where is it that you want to go with your work?” Your article is great food for thought.

thanks all!

This post really means something to me. Developing skills has been really difficult for me the past few months. It's reassuring that this process is grueling for others as well.

This is an absolutely fantastic article, and it really inspires. Thank you for sharing this with us!

This is great, David!

This sounds like a rewarding way of looking at others work. I'm kind of excited to rummage through my favorite Spectrum volumes with this new set of lenses and see what I can find out about myself. Wonderful advice.

great post!

Wow, Muddy Colors is always informative but this is something I really needed to hear today. This is such a great post and the last paragraph suggestion is especially helpful. Thanks so much, Dave!

OLMOCR leverages advanced large language models to extract text from any Image or PDF for free, with unparalleled accuracy and intelligence. OLMOCR now supports over 12 major languages, including a wide range of handwritten scripts.