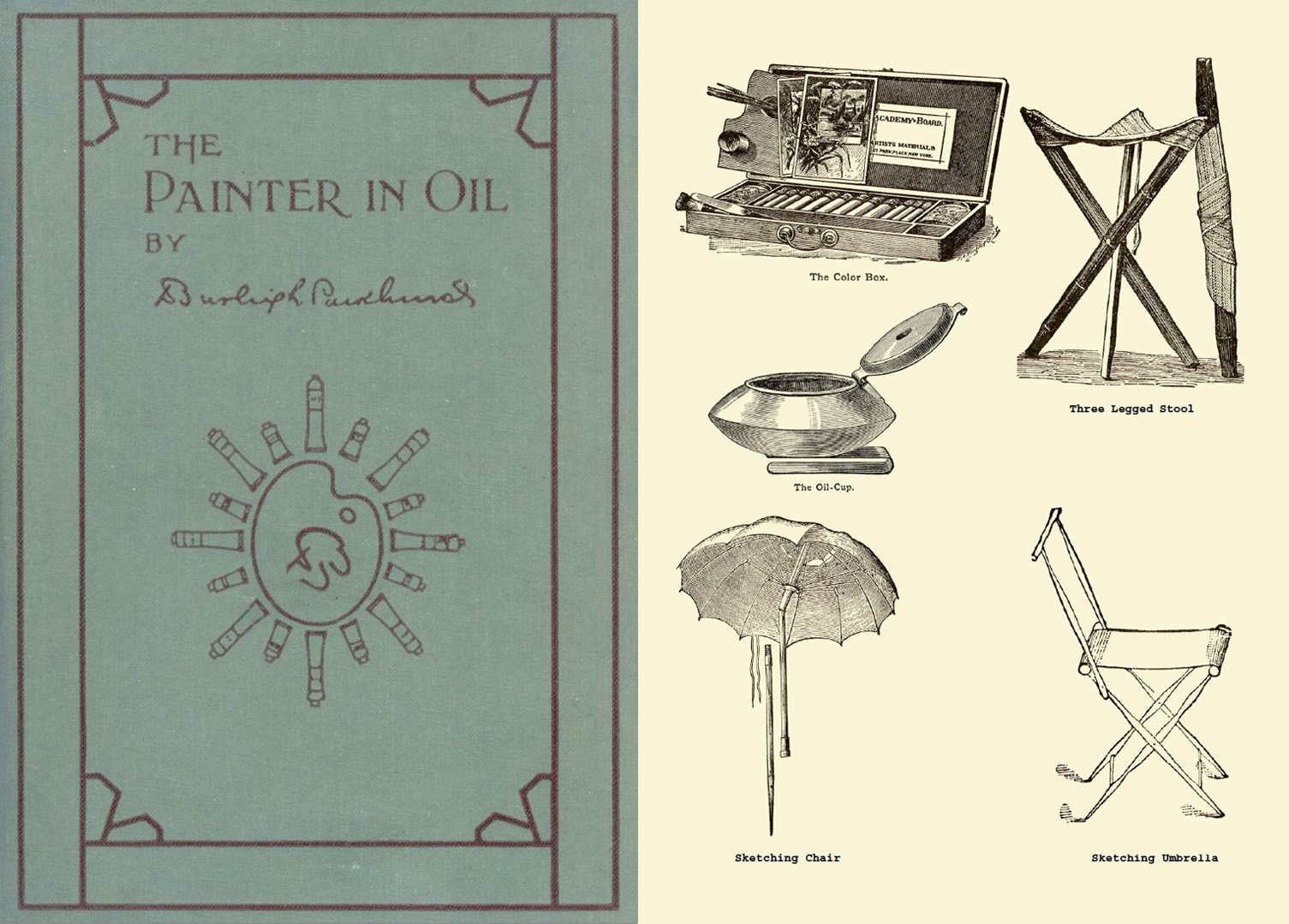

|

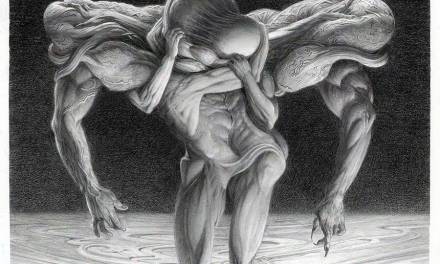

| “Cochise” by Greg Ruth |

G. Straight off the bat, because I get asked this a lot as I’m sure you do. What do you personally prefer as a general term for native peoples… other than obviously, native peoples? We’re living in a time that is far more sensitive to the terminology we used to sling around haphazardly, and I guess that’s a good thing overall. “First Nations” is misused a lot to cover all tribal cultures on the continent when it’s particular to Canadian tribal communities and not meant for say. “Native American” seems to be our overall accepted term, but I gotta confess I wince at it for the same reason I do at “African-American” or “Asian-American” because it carries within it a back door assumption that the only un-hyphenated core Americans are white people, and the rest are dilutions. “Native” is the most definitionally correct term, but I’m a talker and writer so I like to have different words for the same thing to keep the dialogue interesting.

I often use the term “Indian” in conversation, and I find there’s a funny response I get depending on the crowd: White people shrink because I think given it’s essentially a misnomer, and it’s previous cultural history remains and when spoken by me, a white guy… (i.e. cowboys and indians), well it makes other white people nervous I think along the same lines as darkly archaic terms like “colored” or “negro”, terms I heard a lot down south growing up. The natives I have most often spoken to lately are fine with it. When I asked an Apache friend why it made him smile he confessed “Well Greg, I’ll be honest- I love the term because it’s not insulting to us per se, but it makes you the white guy, look silly for not knowing where you were when you named us this. There’s a part of me, and a lot of Indians who do delight a bit in white people looking silly and it puts them off balance”. But beyond that childish prankishness, I think when people are uncomfortable or off balance, they’re more ready to be receptive to something new. Confidence is the death of learning you know.” So I like that it has a Woody Allen goofy me culpa thing to it. And there’s some core truth in pointing to its ignorance as I think that particular quality, ignorance, was what helped fuel the difficult relationship we’ve had and continue to have. It always starts an interesting conversation, and to me, that’s the best medicine: that we break all the silence by having a conversation.

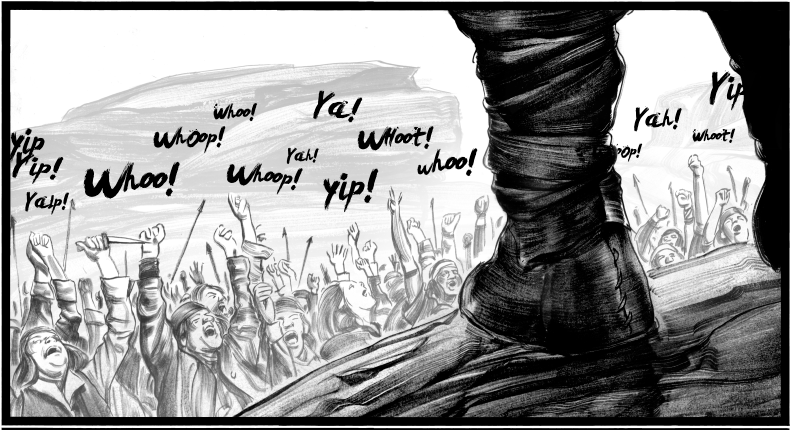

|

| “The Last Ride of Victorio & Lozen” by Greg Ruth |

G: Language is so consequential isn’t it? Okay, so let’s get this thing in gear… Maybe it was growing up in Texas, or maybe it was just growing up in the 70’s & 80’s, but native stories and culture were always something that really fascinated me as a kid and clearly still does today. Granted it was largely to paint them as some wild elemental evil that the pure and goodly white settler had fight against like they were the winds of sin itself, but for this little white dude growing up in Nixon’s America, it was the only place I had to start, and absent of any other exposure I remain grateful for it, despite it’s ridiculousness and terrible approach to showcasing these rich societies. America’s not an old country, particularly as compared to most others, so in many ways local Comanche or Apache tales were like a secret history of our true selves… but they were always kept behind a hushed curtain like an unwanted relative at a funeral. I remember finding arrowheads, in our yard, or out in our soccer fields. They were both a rare luminous thing and sort of walkaday normal like finding a stray $50 bill or a four leaf clover. For me though that tangible moment of discovery, holding this spent weapon in my hand made all of it, the soccer field, my suburban neighborhood, the city itself feel like a thin coat of cheap paint over a hidden kingdom buried by time. I remember showing it to my parents wide eyed as to how how cool it was as a thing and a moment, but also noting the dry swallow that quickly followed when we started talking about the tribal people that left it here. We have, as non-tribal Americans, a really soft and uncomfortable relationship with ourselves and the whole conversation itself when it comes to talking about tribal culture. We just don’t seem equipped on a basic level. I think it’s still tricky to start talking about them- especially as a white person. Why is that? Guilt? Do we lack enough knowledge to know where to start? Is it simply a legacy of post colonial shame? And how do we get past it? Should we?

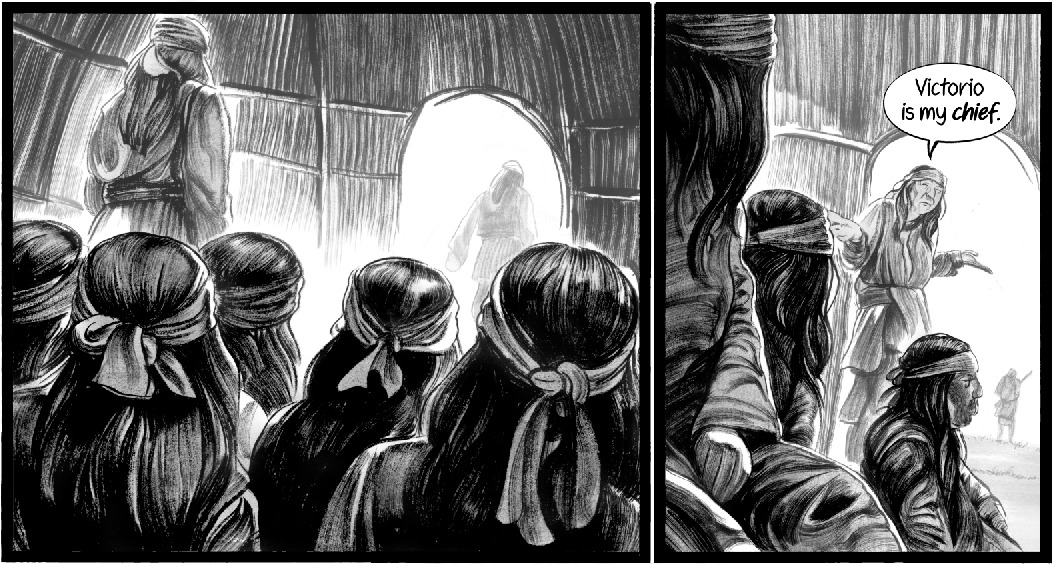

|

| “Young Dancer” by Winona Nelson |

W: I’m still learning just how lucky I was to grow up in my tribe’s land, surrounded by our culture even though I grew up in the city. Even in public school in Duluth, Minnesota, I had Ojibwe language as part of my elementary education.

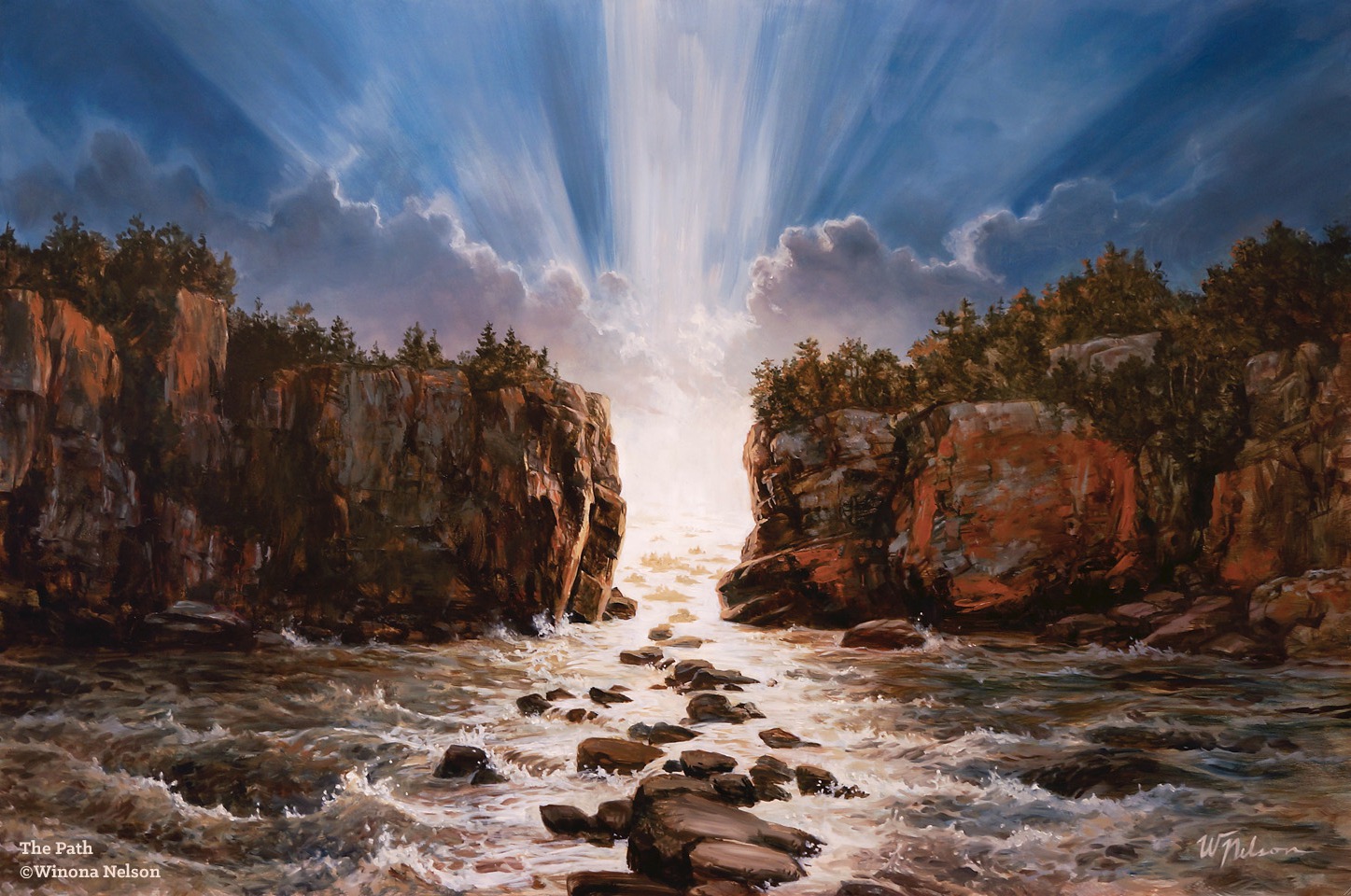

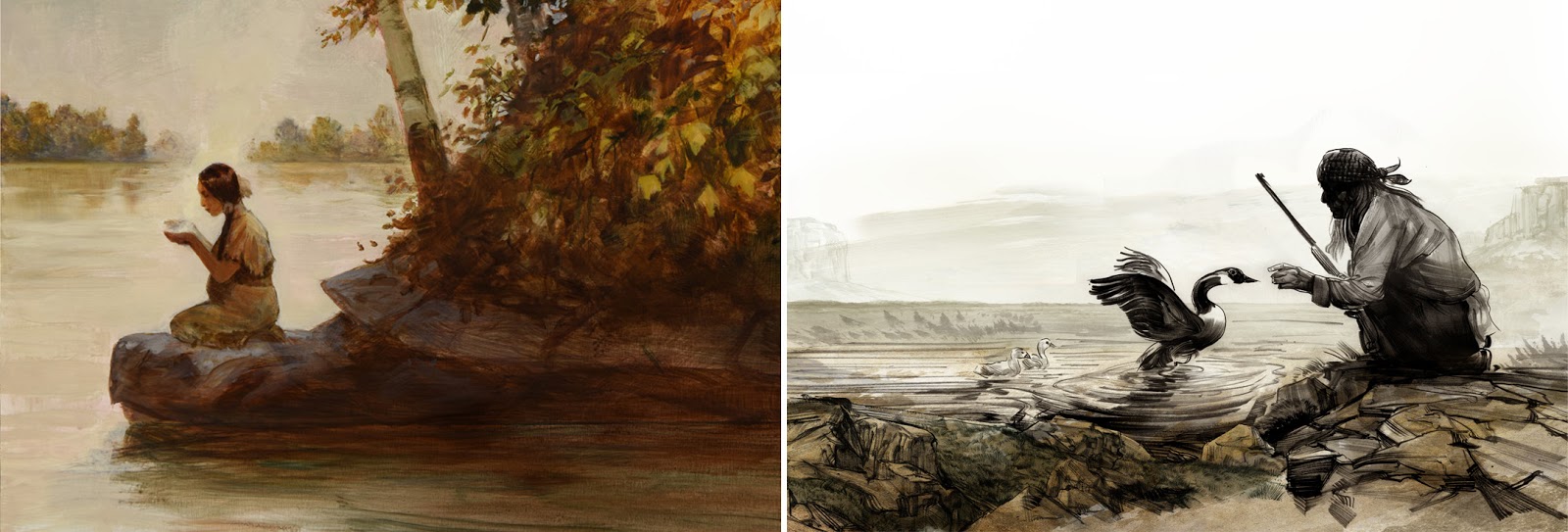

|

| “Spirit Place #1” by Winona Nelson |

To me, our stories are a mysterious secret history, yes, but it’s my own history, not simply that of this land. Each time I learn more about my tribe I have a different kind of guilt than a colonizer’s guilt – I have the guilt of realizing how much I’d internalized and believed stereotypes and narratives that told me my own color is inferior. I mourn the choice to move away from my tribe’s ways before I had even really known them, because I know now that that choice was based on valuing the white world more highly.

|

| “Old Naiches” Greg Ruth |

|

| “Ohukakan” by Winona Nelson |

W: Your point about the draw of an ancient home is a good one. Being connected to the place you live is so important psychologically, and for many Americans whose families came here as immigrants more than one generation ago, there’s a feeling of placelessness. You no longer feel like you’re from Europe or China or wherever your family came from when you have grown up in the US, whether your family is one that spoke the language and ate the cuisine of the Old Country or was one that intentionally buried its cultural connections to assimilate and become American. But at the same time, there’s a guilty little voice telling you that no one can be truly, truly American except for Native Americans. No one else has lived here long enough to have actually evolved with this land, been nurtured and sustained by this land, learned the secret knowledge and magic of this land.

|

| “Geronimo & Lozen” by Greg Ruth |

G: I think that’s such a smart way of codifying the nervousness. And I can only speak to general white nervousness and fear of the conversations from my own perspective, but I have found the more I have come learn about the import and depth of feeling, both good and ill from the native perspective, the more nervous I am to address it simply because I now fully get how serious this is for tribal people. At the same time there’s an aspect of racial discussions like this that cause we of the anglo persuasion, to retreat fearfully for this guilt-fueld fear of fucking up. It’s sort of the inverse of the terrorist who only have to succeed once to be successful… white folk only need get it wrong once to undo any and all good will they have built up to that point- especially in their own eyes. And so the result is a fear to risk that and not engage. Which as hard and tricky as the conversation might be otherwise, the silence to me is the worst insult.

The result then seems to be, in our art, that as a white fellow and ostensibly more free to create and delve into any story, I am also less free to engage in native tales because of the history of appropriation and misrepresentation my race has so excelled at in the past. I wonder if there isn’t an inverse responsibility that you, as an Ojibwe feel you must carry as a banner of your tribal heritage regardless of where other interests may lie. This sound right? As a white fellow here I am brought up to be anything I want, to go anywhere I please, and there’s no underlying responsibility to attend to as a result despite the actual requisite responsibility to right the record on what our fore-bearers screwed up so magnificently and for so long. As a white artist I feel a much smaller sense of obligation to this that I would presume a non-anglo may, especially in there hyper polarized and explosively racial times we find ourselves in.

|

| “Guardian of the Eastern Door” Winona Nelson |

W: I’ve had many instances of people asking my opinion or asking me to participate in their project because it has a Native American inspired setting or theme, but it started only after I began promoting my own personal work focusing on my culture. In my case, Native American is never a curious person’s first guess about my race when they meet me. But I am obviously non-white, and that affects how others speak to me and treat me whether they’re getting the nationality right or not.

|

| “The Murder of Mangas Coloradas” by Greg Ruth |

G: It is new in many ways. I mean I’ve done children’s picture books- two now, that deal directly with veteran’s issues and stories, whereas I am myself not one nor have any direct ties to military life. But the scale and import of that genre and world in terms of conversation are wildly less fraught than a white guy telling a native Apache story is. I don’t questioned nearly as much as I expected- I think Ethan was surprised by this too. We spent months prosecuting each other on this issue to make sure we really thought through how to respond in a way that was the most honest and sensible as we could be. The vast majority of occasions where this has come up, have almost been universally from white questioners who seem to be wrestling with their own white guilt, consciously or unconsciously. Which I find really curious. Reminds me of that old line about where white v black racism is rooted- which is obviously, with white people who started the cycle. In a perfect world it shouldn’t matter what racial background drives someone to tell a story. But the truth is it does to some degree and for different reasons. To question our qualifications is an inherently racist question on its face, but unlike most racism going the other direction, we recognize it comes from a place of deserved skepticism. When we were researching how to full authenticate the kind of racist hateful attitude of a character like John Ward in our story, or that of some of the soldiers in Gatewood’s camp in retreat that led to the horrendous murder of Mangus Coloradas, it was really damned easy to find a hefty pile of material on racist ideas about the Apaches and indians in general. I’m talking Atlantic ocean sized piles, and in comparison there’s barely a handful of authentically told native characters to balance that against. So I get it, but and surprised we didn’t also get it more so far. To us it’s an important conversation and one we’re happy to have. We simply came at this story, as we responded to one patron in the audience at the Barnes and Noble event last June, from a place of love. It sounds hokey, but we really did, but a specific kind and type of love that comes from approaching it from a place of art rather than politics. I think there’s an incredible neutrality amongst creatives- a sort of universal club membership that allows us to share and toss around what might otherwise be political or socially dangerous grenades easily without too much fear of their detonating. It’s not always the case of course, but coming from that place, looking at these stories and people as people and stories of interest unto their own-selves, sort of dodges the racial minefield that usual exists with something like this. It’s a commentary on how low the bar is when its revolutionary to tell an Apache story from the Apache perspective and to make of them rich and knowable human people. I would hope that anyone going into INDEH might come away from it having those concerns evaporated. If we did our job right then they should. Ethan always likes to bring up how if Shakespear were alive during these times he’d absolutely write plays about the American Indians. Particularly about the Apaches because their tale is so dramatically epic and vivid in ways similar to a King Lear, Henry V or Macbeth and Hamlet.

|

| “Geronimo & Son” by Greg Ruth |

As an artist the terror of taking this on is a reason to do it. We’re made better by pushing ourselves out of our comfort zones creatively, but I’ll always be a voyeur because native realities were never a part of my personal life experience growing up or even nowadays. So that haunts after any confidence our years researching and drawing these characters might bring. The answer really is to do more of this- and not just us, but more everyone everywhere engaging with these aspects of our shared collective heritage in a way that brings a greater sense of understanding we now lack. Sherman Alexie makes an interesting case for chronic “Indian Bipolarism” which speaks to his notion that all natives in America lead bipolar lives standing between their American selves and their Tribal selves. Does this ring true to you? You seem to embody that in many ways, and for me at least it not only makes the work you do so fascinating to see unfold, but how you operate as an artist navigating between these two. Your tribal self is there and demands to be embraced in your work or ignored so you can freely chase other genres and subjects. That’s got to provide a baseline sense of self I lack entirely as a white artist, don’t you think?

|

| “Third Fire” by Winona Nelson |

W: Sherman Alexie, man, I’m glad you brought him up. I wish I’d learned about him much earlier. When discussing my experience at Native school with a middle school teacher friend of mine, she sent me his YA book The Absolutely True Diary Of A Part Time Indian. I read it in one sitting, without even stopping to go to the bathroom, and it made me cry the biggest, ugliest tears I’ve cried in years. It uncorked a grief I had been holding inside since I was a kid. It’s ridiculous, I’m 32 and it was the first story I’d read told from a contemporary Native kid’s perspective. That book made me realize that choosing the white school was a survival move, and that someone else out there has made that choice too, and has written about it. I was so young then that I didn’t think of it in those terms at all, and hadn’t thought about it much after the fact except as a ghostly guilt that would pop up to ask me if I have the right to be interested in Native stories and issues at all, after making such a choice.

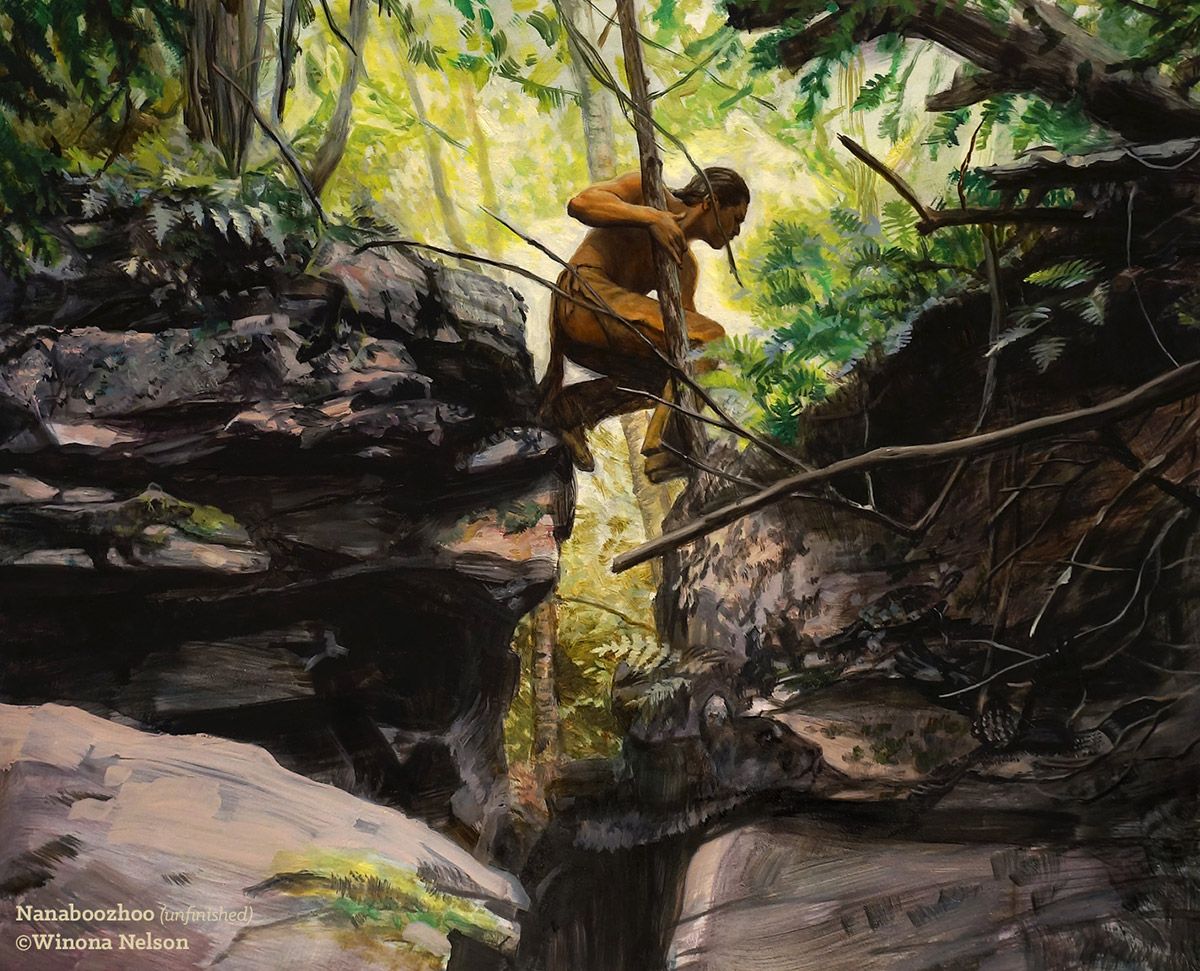

|

| “NanaBoozhoo (in progress)” by Winona Nelson |

The “bipolar nature” is definitely accurate in my case. My Native side was buried away for a long time. I feel like it’s been growing out with my hair now. In some way that was my plan all along, to go to white school and the wider white world and tap into a good living, become a famous artist and come back to my Native side when I could feed myself. It was a naive dream I didn’t tell others because it was so ambitious and arrogant that it was plain embarrassing, but I’ve covered a little ground now so maybe it’s okay to say it out loud.

|

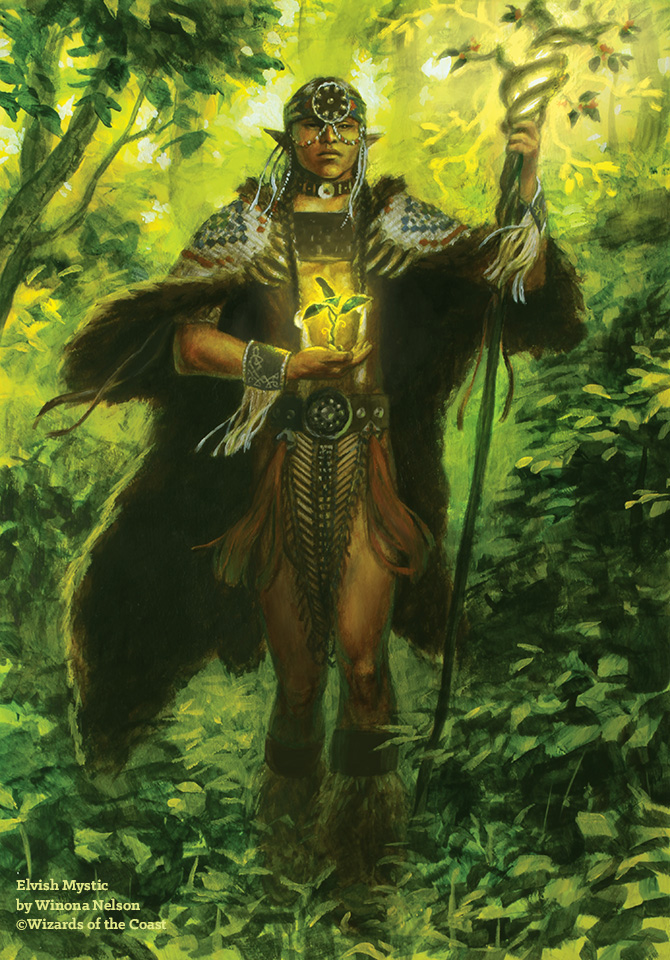

| “Elvish Mystic” Winona Nelson |

To approach Native American themes and treat it as a monoculture, for a Native American person it may not be the most offensive portrayal, but it’s incredibly annoying. The “gift” of being included at all wears thin pretty young. It’s like when you’re a kid and you get birthday presents from relatives, and they clearly know nothing about you because they’ve given you something you have no desire whatsoever to play with or own. Like when your grandmother asks your mom what to get you, and your mom tells her you like Disney movies so Grandma shows up with a badly animated version of Noah’s Ark. It’s a try, but so incorrect you’d rather she just not.

|

| “Geronimo with the Nedni” by Greg Ruth |

G: One of the things I discovered quickly and uniformly working on this book over the last six or so years, was how funny native people are as a baseline. There’s this Edward Curtis picture we have of the mountain faced indian staring into your soul that some of my friends can turn on with terrifying precision, but it is such a tiny corner of the character of a latter day native person overall. There’s a culture of humor there that seems in keeping with what you find in jewish culture and even black culture. A sort of passion for laughter as a response to oppression. We don’t immediately think of tribal people as funny people, but they really can be. Do you find this to be true- seeing this in your own experiences growing up?

W: Oh yes. My dad and his friends were all quick to joke and laugh, even about terribly painful things. It was as if they lived by the rule “If you can‘t make it funny, don’t say it at all”. In my studies I have learned that among the earliest documented encounters two hundred years ago, the main trait about my tribe that stood out to the traders and explorers was that we were constantly laughing.

|

| “Old Nana Chooses a Side” by Greg Ruth |

G. That is so fascinating to read, and seems absolutely spot on. It kind of provides a great deal of hope in myself, especially as a creative that we get to be in a time of healing and growth like that. i hope we are and it continues to grow and gather steam. I am a bigger and better person for having delved so deeply in Apache culture these last few years. It’s been an entirely additive experience and has really helped me in my own clumsy climb out from Texas born racial dumbness and insensitivity overall as well. It puts a duty upon us as artists I think. For me as a mission, art requires of itself to do good. Good doesn’t have to mean lollipops and rainbows and hugs for all the lovely souls out there. It can mean fire and destruction and controversy as long as it really keeps us moving forward and evolving. For me personally as an artist, Native stories are so perfect I think because they are so visual and so poetically delivered as to inspire visual imagery. I don’t know if the largely spoken language and oral history tradition lends itself to this characteristic, but it’s there regardless and rich with inspiration and potential for any artist or writer from any culture. As a force for good it does that too- and foremost because this is art’s public face- the one everyone sees and the voice everyone hears that changes how they might see the world. Indian stories do that so powerfully and in many ways so much more than other indigenous or old world mythologies, perhaps because these are our stories. They come from here and speak to where we are. However terrible the interaction between the colonials, it feels to me like it’s time to bring that wound together and heal, and share and exchange these things with ourselves as a whole people in this melting pot of a place. The early Indigenous tribes took it on the chin at a scale almost unparalleled in human history. They’ve got some good coming to them by miles. There’s a lot of good in changing how we speak of them and to them and to each other. That kind of ethos is long overdue and I think art is a near perfect bridge to join us. Because through art we can get around the prejudices and go right to the heart. We can raise our kids on art that teaches them, before they even know language, what the world can be or should be.

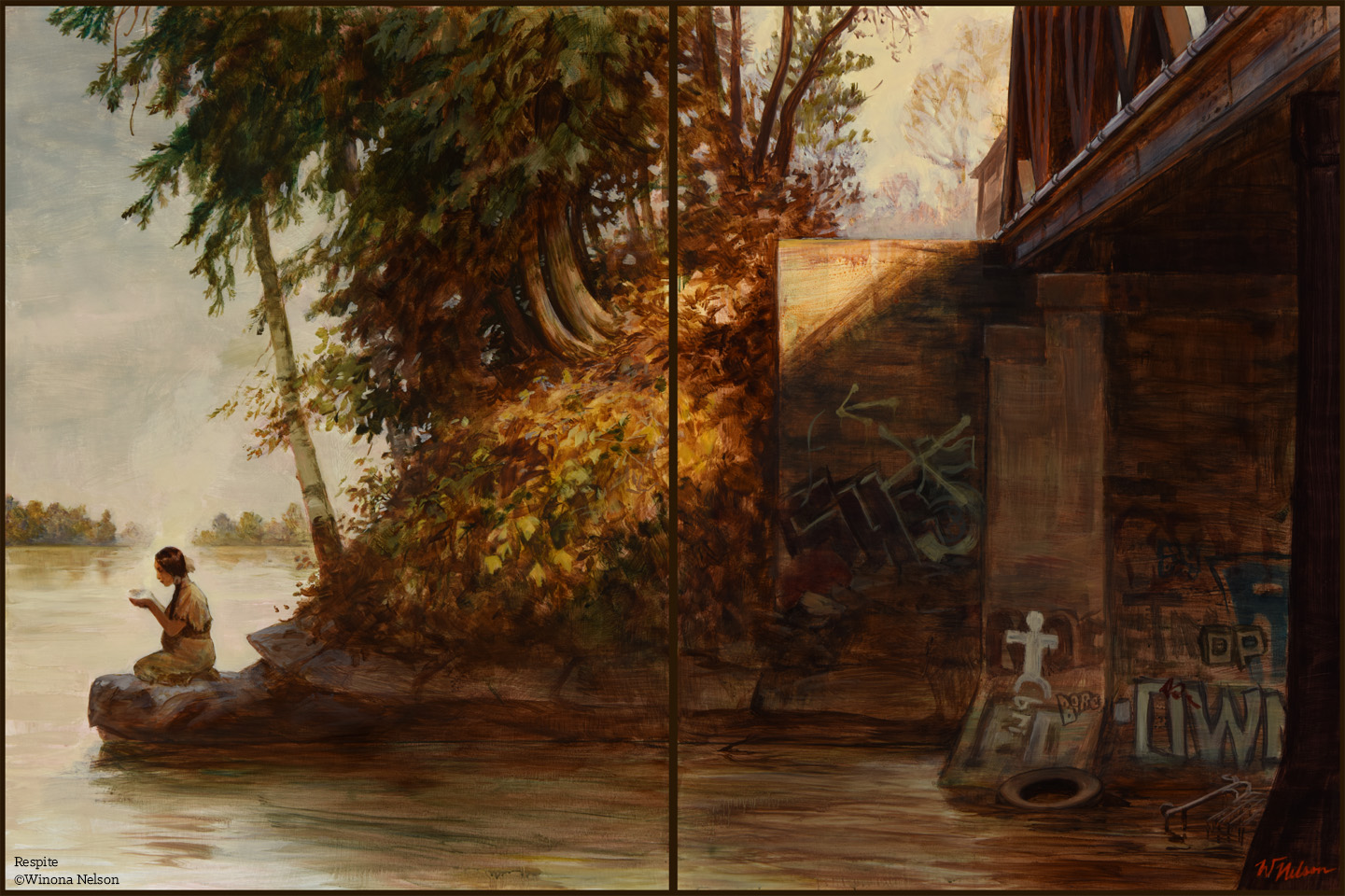

|

| Winona Nelson |

W: The seventh prophesy of the 7 Fires of the Ojibwe told of a chance for all of us to choose again whether we will wear the face of brotherhood or the face of death. In order for either of our cultures to survive, we need to come together and learn from each other.

The place we live shapes us and nurtures us, and is a part of us. The echoes of the generations makes us who we are. It‘s an effect that’s multiplied by the oral tradition, because stories were tools for disciplining and educating the listener. They were tailored to the situation and the individuals hearing them. The storyteller was never just telling us about the things in their story. They were telling us about ourselves. That essential, oracular purpose rings through the ages because it has already made us who we are.

Recent Comments