What is a Mental Model?

This is going to be the first in a series of articles breaking down small but powerful mental models for painting and drawing. Firstly: what is a mental model? A mental model is a container idea or phrase that helps an individual to categorize and access broad swaths of information.

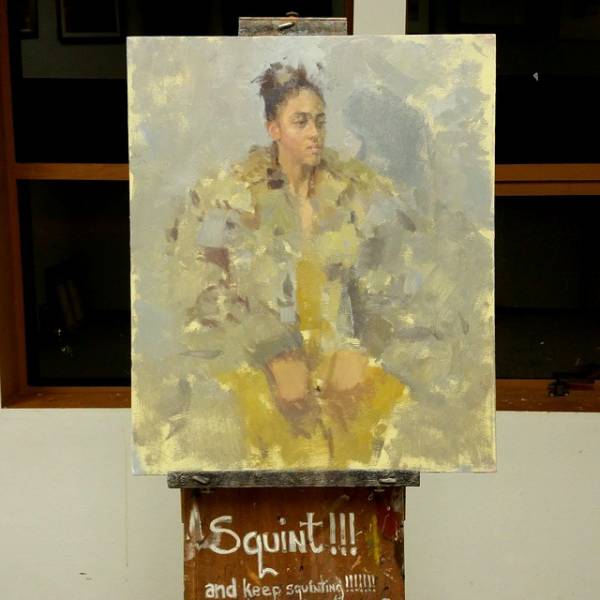

Maybe you’ve seen how many plein-air and figurative artists write “SQUINT!” on their easels. For them, “SQUINT!” is a mental model; it recalls to them a vast pool of information about how to think and organize what they’re seeing, and also about what they need to do physically to encourage that state.

Another simple, non-art explanation is: any word. The word “dog,” for instance, recalls to you all sorts of information about the creatures: they are furry, they have four legs, they wag their tails, they are kept as pets, they bark, etc. When you see a dog, even without thinking about the word “dog,” all of this information is instantly available. You just know what a dog is.

This is the power of successful mental models: when they’re functioning well they slip easily to the background and govern our thoughts invisibly, making us better. This is also what makes them tough to track down, and why it can be agony trying to get another artist to explain to you how or why they’ve done a particular thing on the canvas. For those who haven’t studied mental models in depth*, each high-functioning principle they use is now part of an intricate tangle of “everything that works,” and is no longer a conscious part of the battle.

Despite the difficulty of organizing our thoughts about our own thoughts, and transferring that information to another artist, it can be done! The best teachers have simple, elegant container ideas – seeds – which they’re able to hand off to students. If done properly, these small but powerful mental models continue to unfold year after year in the recipient’s mind, blossoming into a vast network of skills that all fall under and are governed by the original container idea.

The Soft Zone

The first mental model I want to share here is “The Soft Zone.” This is a state of consciousness in which you’re at your most powerful and flexible, and is a precursor to a number of other artistic abilities. Its opposite is a “Hard Zone,” in which you’re quite fragile mentally, despite pouring all your effort into “staying focused.” Let’s explore this mental model through the experience of an individual.

In his book, The Art of Learning, author Josh Waitzkin (subject of the feature film Searching for Bobby Fischer) describes his difficulties focusing at the chessboard as a young player, particularly in the maelstrom of media attention that followed the release of the aforementioned film about his career:

“I often found myself thinking about how I looked thinking, instead of thinking about the chess position in front of me.”

Ouch; that hit really close to home. We’ve all been there. Have you ever been drawing at a figure drawing class, and briefly found yourself wondering how the drawing on your pad looked to your neighbor? This is a bad place to be – you’re not really thinking about your drawing anymore, and your next marks are doomed to mediocrity.

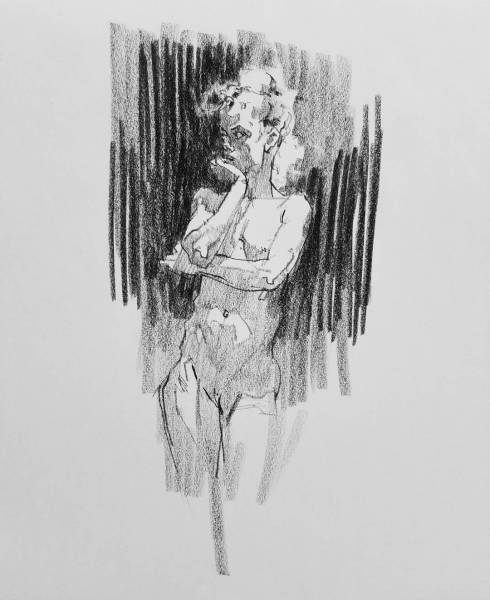

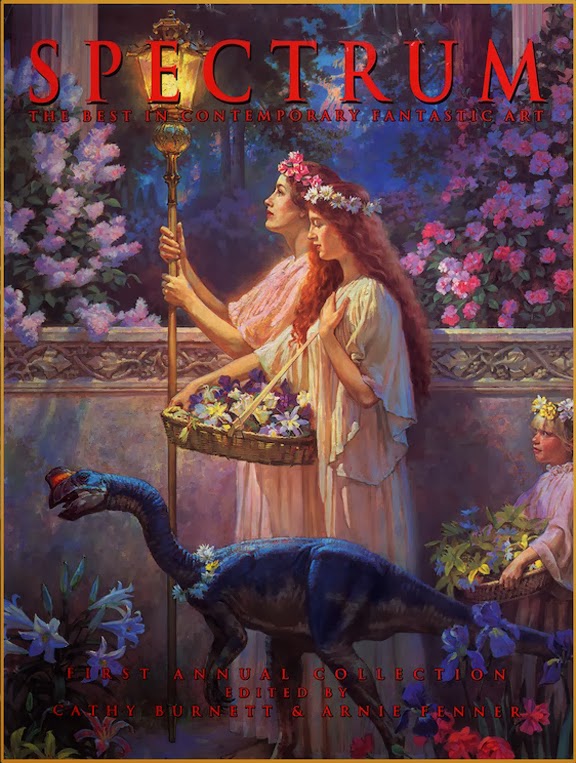

A figure drawing from Aaron Coberly. There is just no way to draw like this while thinking about how you look drawing.

Josh faced an additional problem, which was that in tournaments his concentration would collapse inwardly when he faced distractions like “having a song stuck in my head,” or pressures such as “having to play a game against my own coach.” In the former scenario Josh totally lost his ability to think clearly about chess, whereas in the latter he clenched up, focused hard, and generally came through the fight – but afterward he was totally spent, and couldn’t focus on subsequent games.

Josh eventually found a solution: The Soft Zone. Josh explains that in a Hard Zone, you’re rigid, brittle, and prime to shatter – like glass. You’re pouring your effort and energy into a forcefield around yourself, which is ultimately unsustainable. Since you feel that you must repel any incoming stimulus, or expel any internal distraction, each new thing that arises to challenge your focus actually demands some of your focus, like heads on a hydra.

In a Soft Zone the mind is more fluid. Instead of resisting stimuli, the brain folds “distractions” into its processes, thereby dissolving them. Flowing like water, our focus rises to challenges suddenly and can ebb just as quickly, which helps us avoid the fatigue of prolonged over-exertion. Two birds, one stone.

Why do we need it?

So how does all this apply to art-making? The Soft Zone is the perfect place to be while making marks. In addition to warding off distractions (someone’s cell phone going off in the middle of figure drawing), and disarming external pressures (that looming deadline, or the fear accompanying the first BIG client job), The Soft Zone makes possible the maximal expression of our skill.

Will Jonathan, a sports Mental Coach, was the first one to turn me on to the idea of “maximal expression.” His point of view is that everyone has a current skill number, which they can raise over time through hard work. Let’s say from 1 to 100 you feel like you’re a 21 at art. 21 is what’s inside you right now; it’s your potential. Now, you also have a second number floating above your head at all times, a variable number. This second number changes based on things like how much you’ve slept and whether you’re relaxed or stressed. This number is your current expression of your inner number, and therefore maxes out at 21. This variable number is what actually comes out on the canvas, and is the only expression anyone but you can see of your skill.

For someone who’s a 61 at art: on their best day, they paint like a 61. But when they’ve been up all night and the painting is due in 4 hours, maybe they paint like a 26. Yikes. We always want to position ourselves to express as much of our ability as possible. The Soft Zone is a mental framework that enables us to perform at or near our maximum with much greater consistency, and even turns on some skills that are otherwise impossible.

Consider the words of Kim Jung Gi on drawing:

“So in order to avoid [small but painful mistakes] you need to draw paying attention to the bigger picture. You can’t loosen up too much. But then again, it gets difficult to draw if you’re too tense too. What an enigma.”

Sounds like a Soft Zone to me.

How can it be achieved?

Ok, so we definitely want to be in The Soft Zone. How do we get there? To answer that question there are two things we need to appreciate:

- Firstly, that our level of physical distress (how amped up we can get ourselves) has nothing whatsoever to do with our cognitive clarity. In other words: you can still be sharp as a razor without relying on “clenching up” and TRYING HARD DUDE. Stress-induced focus is the unsustainable kind, the Hard Zone. Stress can only hurt us.

- Secondly, that “trying to focus” is futile. Focus comes from full engagement with challenges because it’s a biological mechanism adapted to help us survive. If something isn’t challenging the brain just won’t focus on it. We need to work in a way that stimulates and challenges us to “turn on” periodically. Focusing on art – at its best – doesn’t feel like focusing on art; it feels like not focusing on anything else.

If you’ve ever watched Kim Jung Gi draw live in people’s sketchbooks, you’ve witnessed a version of The Soft Zone in action. He takes in the crowd and interacts with them, all while producing marvelous work – and he never seems even the slightest bit worried.

What actions do these appreciations lead us to? We need to avoid either physical or mental sources of high stress, because each can trigger the biological stress response that will shatter our Zone.

Before painting: get enough sleep, be well-fed, and establish a comfortable working environment. Use good ergonomics. Realize that very little is on the line while painting. As my first teacher Brian Stelfeeze is fond of saying, “If I make a bad painting, I don’t suddenly have cancer.” We are only playing to win; we basically can’t lose.

During painting: Take breaks! Divide your work into established “sessions” so that you have cues to get up, walk around, stretch, and rest the eyes and the mind. Short (30 minutes or less) naps are a hallmark of top performers in a number of fields*.

The best masters have even devised ways of slipping micro-breaks into their processes. You can completely relax your brain while you mix your paints, and return to the canvas just a moment later totally refreshed. You don’t have to hold the problems in your mind all the time – you can ebb and flow. I’ve seen line artists focus at the beginning and end of a line, but briefly look away as their pen travels the middle of the line. Unthinkable! They are taking tiny breaks all the time. This pulsing application of focus is at the center of the ability to stay inside The Soft Zone for prolonged periods of time, and why The Soft Zone is sustainable. You’re always on; you’re always resting.

To deepen your ability to focus and relax suddenly, two exercises recommend themselves – one physical and one mental.

The people at the Human Performance Institute have found that interval training done on the body actually increases the mind’s ability to pulse on and off as well. Sprinting up to an intense heart rate, then walking and trying to breathe deeply, relax, and recover as quickly as possible to a light heart rate – has a profound effect on the mind.

Additionally, the full-body “flush” of a sudden sprint or bout of pushups can be just what the mind needs to reset in moments where your concentration is flagging. I love these little physical hacks.

On the mental side: meditation or other focus-centric activities work pretty well, despite how hype meditation is right now. The whole point is that focusing on just breathing is difficult. By forcing the mind to “return to your breathing” and fold in distractions as each one occurs, you train the mind to move quickly from distraction to focus, over and over. Meditation is pretty widely mis-understood so I recommend some cheap instruction rather than an internet search to get going if you decide to explore this avenue. More simply: stop taking your headphones to figure drawing. Spend a few weeks letting the outside music and noise in, and rolling with it. Can you learn to think to the rhythms of the outside world? Can you return to focus after a cell phone goes off? This is EXACTLY meditation.

As you build up reps of “returning to focus,” and weed the physical and mental stress out of your art-making, you’ll notice a profound difference in your ability to enter and sustain The Soft Zone. You’ll see that new skills open up and fold in to your dynamic understanding – that you actually seem to be able to put down what you know. In time, “seeing wide” (what Kim Jung Gi was talking about) and other abilities that require a lot of presence will become available to you.

We’ve talked about an awful lot, but we can tuck it all neatly inside one phrase: The Soft Zone. The next time you sit down to work, if you do nothing else we’ve talked about, mutter “The Soft Zone” to yourself as a reminder of how to be. Become relaxed, yet dynamic – like water, and express your full potential.

______________________________

* The bible on mental models is Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise, by Anders Ericsson and Robert Pool – though they call them “Mental Representations,” which I myself find to be too awkward a mouthful to be useful in conversation.

* The science of naps is covered in When by Daniel Pink, and Sleep, by Nick Littlehales, both of which I fully recommend.

Thanks for this, Tommy! Mental models are something I’ve been attentive to as I learn over the last few years and they are invaluable. This one especially seems like a revelation.

Great article Tommy, I am so honored to be referenced.

Thank you.

-Aaron

Even if there are many definitions of what a mental model is, some of them quite flexible, I can’t agree with your definition because a mental model or representation attempts to picture (model, imagine) how things work or fit together. A mental model is similar to a physical model as it attempts to abstract some of the important features of the reality or some aspects of it.

An idea or concept can be associated with a mental model though it has more the role of an anchor or label for one or more mental models, the context allowing us to identify its full extent and its meaning. Therefore, a label as “Squint” can’t be a mental model, but is associated with the mental models people have on a certain topic.

A phrase can attempt to describe a mental model, while a mental model can be built to understand or describe a phrase, however I wouldn’t put an equal sign between the two.

Yes, a mental model helps an individual to categorize and eventually “access” broad swaths of information and make sense of them.

To get an idea how various philosophers and psychologists defined mental models you could check my extensive list of quotes on the subject:

http://the-web-of-knowledge.blogspot.com/2019/01/mental-models-quotes.html

Thank you, thank you, THANK YOU for this profound comment. I had to think about it a long time. My own understanding and examination of Mental Models is rather nascent, and as you can see I’d made a critical mistake: confusing Mental Models for containers, when in fact they are structures. “Squint!” is the name – but the actual Mental Model that may be contained within the single word “squint” is rather large and complex – hence the difficulty in untangling it, and passing it on intact. Do I seem to have that more right? I want to rectify this misunderstanding in a later article…

This is something new. I’ve never heard of mental model before.