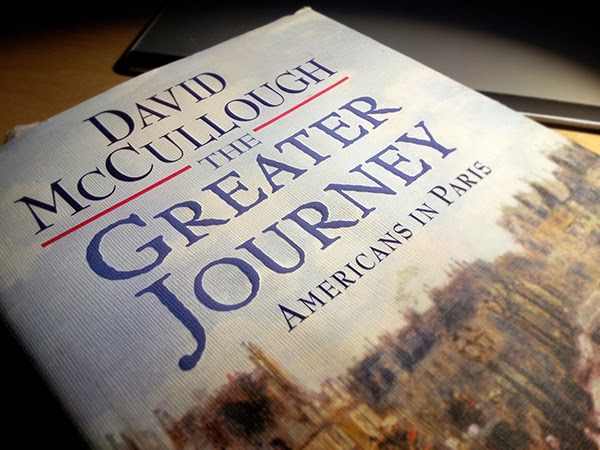

I thought it would be interesting to do a book review and recently finished reading David McCullough’s The Greater Journey. I have enjoyed many of McCullough’s books, John Adams and The Great Bridge being right up there at the top, but this book was really inspiring to me as an artist. Honestly, when I finished I felt both energized about the work ahead and motivated to raise my personal goals and expectations.

“For we constantly deal with practical problems, with moulders, contractors, derricks, stonemen, trucks, rubbish, plasterers, and what-not-else, all the while trying to soar into the blue.” – Augustus Saint-Gaudens

The overall drift of the book is about the journeys and histories of Americans traveling to Paris to study, mostly art and medicine, or just those seeking some inspiration. The time period begins about 1830 to the end of the 19th century. The journeys are set against plagues, war, revolution, world fairs and the building of the Eiffel Tower and the Statue of Liberty. It is a fascinating and informative read.

Part of the reason I was excited to write a review of the book here on Muddy Colors, was my recent trip to New York, where I saw some of the paintings and sculptures discussed in the book. I took some pictures to share along the way (the photos of the Farragut monument are not mine nor is the image of Samuel Morse’s Louvre painting). I will recount stories of two of the artists, painter Samuel Morse, and sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, but know that there is so much more in the book.

The book starts off talking about several artists, including George P. A. Healy and Samuel Morse. Morse would ultimately be known for his invention of the Morse Code and promotion of the telegraph, but before that, he was an accomplished painter. Most of those that travelled to Paris were in their mid or early 20’s but Morse set out at the age of 38. He had just lost his wife and sought new inspiration. He left his children with relatives and set out for a fresh start. Also traveling with Morse was James Fenimore Cooper, author of Last of the Mohicans, with whom he would become fast friends.

Traveling across the Atlantic was no mean feat in those days. It was dangerous, tedious, taxing and unpredictable. It could be done in as little as 3 weeks, but 6 was much more common. It was also expensive and most of those who went, relied on parents or some patronage to make the journey.

Once past the rigors of the journey and sea-sickness but a bad memory, the travelers made their way to Paris. Paris at this time was still a rather medieval city. Noisy, smelly, narrow streets zig-zagged through the city, requiring a strong stomach and stronger will to navigate. Still, the city was the center of art, medicine and possibilities.

Samuel Morse

Samuel Morse was determined to create an epic painting, return home triumphantly, riding the masterpiece to fame and fortune. He set out to paint a scene in the Louvre, creating a fictional scene containing a selection of 38 of the greatest masterworks in the museum. Because many Americans had not and would not ever travel to Paris, he figured that it would both educational and a huge attraction to have so many paintings faithfully reproduced in this one image. James Fenimore Cooper spent many hours at his side, writing that Morse had “created a sensation” at the Louvre with the start of his large 6′ x 9′ canvas.

Morse would work for nearly two years, even painting through a cholera epidemic that would kill thousands, Cooper by his side nearly every day. Cooper, during this time was making huge amounts of money from his book sales and achieving great fame on both sides of the Atlantic. He was seen as the quintessential American abroad.

Morse’s painting, The Gallery of the Louvre, is quite impressive, copying the styles of the great works copied with high skill. Among the figures observing the paintings in the scene are James Fenimore Cooper and his wife and daughter (on the left in the corner). Morse himself is front and center, giving input to a young female student. Morse finished the last bits of the painting in New York, traveling home in 1842. It was on the trip home that he first spoke of an electric telegraph according to Morse.

When completed, the painting was met with enthusiastic reviews from the press, but the public showed little interest in the piece. Morse’s dream of earning great fortunes exhibiting the piece, was not to be. In 1982, it was sold for $3,250,000 then the largest sum for an American artist.

Morse went on in his career until he was rejected in his bid to paint the epic scale historical paintings for the capital building. He felt that he was rejected out of political malice and swore that he would never paint again. He was good to his word. It was only then that he began full pursuit of his idea for the electric telegraph. He would later return to Paris to exhibit his invention and seek patents overseas.

I was familiar with the works of Augustus Saint-Gaudens before reading this book, but not specifically, meaning I had seen them, but was not aware of the artist behind them. The Met has a great selection of his work, and The city of New York is rich with his efforts. McCullough gives wonderful details on his marriage to Augusta Homer (yep, Augustus and Augusta, and Augusta was also an artist and first cousin to Winslow Homer) and his rise to fame while studying in Paris.

In fact the green light for him to marry was contingent upon his being awarded the prize of sculpting the statue of Admiral David Glasgow “Damn the torpedoes” Farragut. He won, both the prize and the bride. Augustus said that he needed to move to Paris to complete the work, not just because the “art current” was stronger there, but there would be more knowledgeable support there. America didn’t yet have the expertise to pull off a monumental sculpture.

McCullough is very thorough in recounting all the challenges faced and the organization needed for Saint-Gaudens to complete the sculpture. I found this part of the book to be riveting. I love reading about the processes and the great drive of Saint-Gaudens. There seemed to be so many points at which he could have given up, but he didn’t. With each challenge, he pushed on and was all the greater for it.

It was during this time that another great artist, young as he was, came on the scene and made a huge impact. John Singer Sargent entered in to the studio of Carlos Duran. I won’t go into details here, you will need to read the book! It is worth it.

Augustus went on to become the most important American sculptor of the 19th century, creating great monumental and decorative pieces of art. Here are some of his works from Central Park and the Met:

General Sherman is being led by Victory. The statue is bronze, but the whole thing was electroplated with gold. It is stunning. It is located at the south east corner of the entrance to Central Park.

The detail is just amazing on his work. You can look for hours and still find wonderful little details. Look at the braiding on the tassels.

The model for Victory was an African American woman, though it isn’t obvious as she was sculpted with a classical Greek face. Saint-Gaudens thought is was fitting though that Sherman would be led by a black victory as he laid waste to Atlanta and the South. He said that she had one of the most beautiful figures of all his models.

Still smaller than the original which stood on top of the Madison Square Garden building until it was demolished. I haven’t found a definitive source on the location of the original. Some sources say that it is now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, while some say that is also a replica. The image here is of a bronze reduction. It is at least life size while the final statue was copper plate, like the Statue of Liberty, and 14.5 feet tall. At one point, it was the highest point in NYC and the first statue to be lit with electricity.

The stone used was really interesting. The marbling stands out from the body of the stone in relief.

There is much more in the book than just these two artists’ journeys. One of the more memorable passages talks about how they disposed of the many corpses used for dissection by feeding the bodies to a pack of dogs kept behind the hospital for that purpose. The dogs were reported to be fat and well fed. You get to follow Paris as it moves from a cramped and crowded medieval city, through it’s rebirth as a jewel of architecture and beauty and the Franco-Prussian War.

I have made the trip to Paris to study the paintings in the Louvre and d’Orsay, but only for a couple weeks. My efforts feel somewhat humble, if not feeble in comparison to those artists of the 19th century, but it does not discourage me, only inspire me to work hard, following the example of the brothers and sisters in art that went before us. I am grateful that it no longer takes a 6 week ride on a sailing ship though. Great art or no, that sounds awful.

I think at some point, as artists we must all take the “greater journey.” It might not be to Paris, but I think it must be one of new sights and sounds. Fresh views to inspire and prod us from the comfort of home or school. The human spirit is well fed by challenge and setback as long as we are willing to press forward. To quote another great writer, we must all “go there and back again” I think.

Have you packed your bags and stepped out on a quest for greatness? Let me know. Thanks!

Howard, another great post. Look forward to reading this. The great journey, epic.

Can't wait to read this. In 1987-88 I was fortunate enough to have an opportunity to pack my bags for 2 semesters to study art in Rome, Italy. I say “to study art” but it really was so much more than that for a 21 year old kid from Schenectady NY. While the artistic journey changed my art forever the entire experience was more about learning to survive in a strange place. I'm still working on my great masterpieces(ha) to rival the Caravagios and Raphaels and every time I smell the exhaust fumes of city buses I am instantly transported back to Rome. If anyone is thinking about studying abroad all I can say is DO IT!. It will change you for the better. Thanks for the post Howard.

Thanks Bill! You will love the book, but be prepared that you will need to have enough money to fly off to Europe or NY set aside as soon as you are done. I was lucky to finish the book the week I left for NY. 🙂 I need to get back to Italy and Paris though…

Thanks Brian! I know what you mean. I have spent time living in Norway, studying art in France and in Italy. Changed my life. I came back with so many ideas and ready to really work to achieve new goals. Raphael and Caravaggio still float around in my head and nudge my ideas for paintings. Nothing like seeing them in person. It must be experienced that way.

One day I shall go to Europe, but for now, I will content myself with ordering this book from the library and traveling vicariously. Thank you for the book review and photo tour.

I'm a huge McCullough fan. “1776” is a MUST read! (I just added “The Greater Journey” to my Amazon wish list. Thanks!)

As for “Portrait of Augustus Saint-Gaudens” by Kenyon Cox… I know that piece very well. The Met is one of my favorite places, and that piece- as well as Sargent's “Madame X”- are old, old friends.

Thanks!

There is a National Park Located in Cornish NH. http://www.nps.gov/saga/index.htm. I have been and It is a fantastic place for inspiration. Touring the grounds, his home, and his studio in New Hampshire. I highly recommend this one and only National Park Dedicated to an american artist.

Could you provide a jpg of the Susan Walker Morse painting for my book, Caribbean Women’s Art, along with permission to publish?

Mary Ellen Snodgrass

5591 Ashley Court

Hickory, NC 28601

828-324-0155

aphra@charter.net