As a painter I feel it is required that I learn to master portraits.

The study never stops. If a young artist wants to find their way through the pigment early on, the best way to achieve that, to understand color and edges and balance and form and value and light, is to start with portraits.

Faces are familiar. We all have one, look at it practically everyday, and are quite familiar with it. We recognize a portrait pattern quickly and easily in nature or on canvas. Because it is so familiar, it’s one of the most accurate ways to learn how to use life’s color.

Achieving a representation is so flexible, it’s probably the simplest way to capture an object on canvas. It loves to be rendered in every detail, or distorted and contorted beyond belief. There’s a tremendous range of possibilities and yet, it’s still a portrait.

This category is far too large, but I can start with some of my personal favorites.

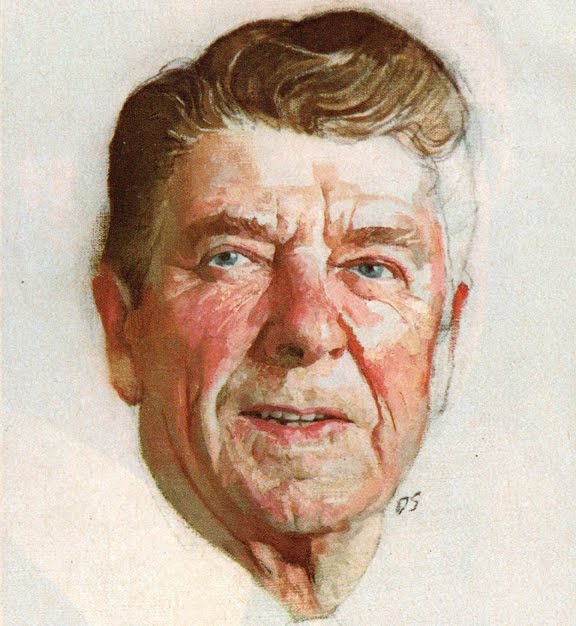

The killer part of this portrait by Daniel Schwartz is the lack of pigment in the reflected light that gives that unfinished feeling, but you just know it doesn’t need to be.

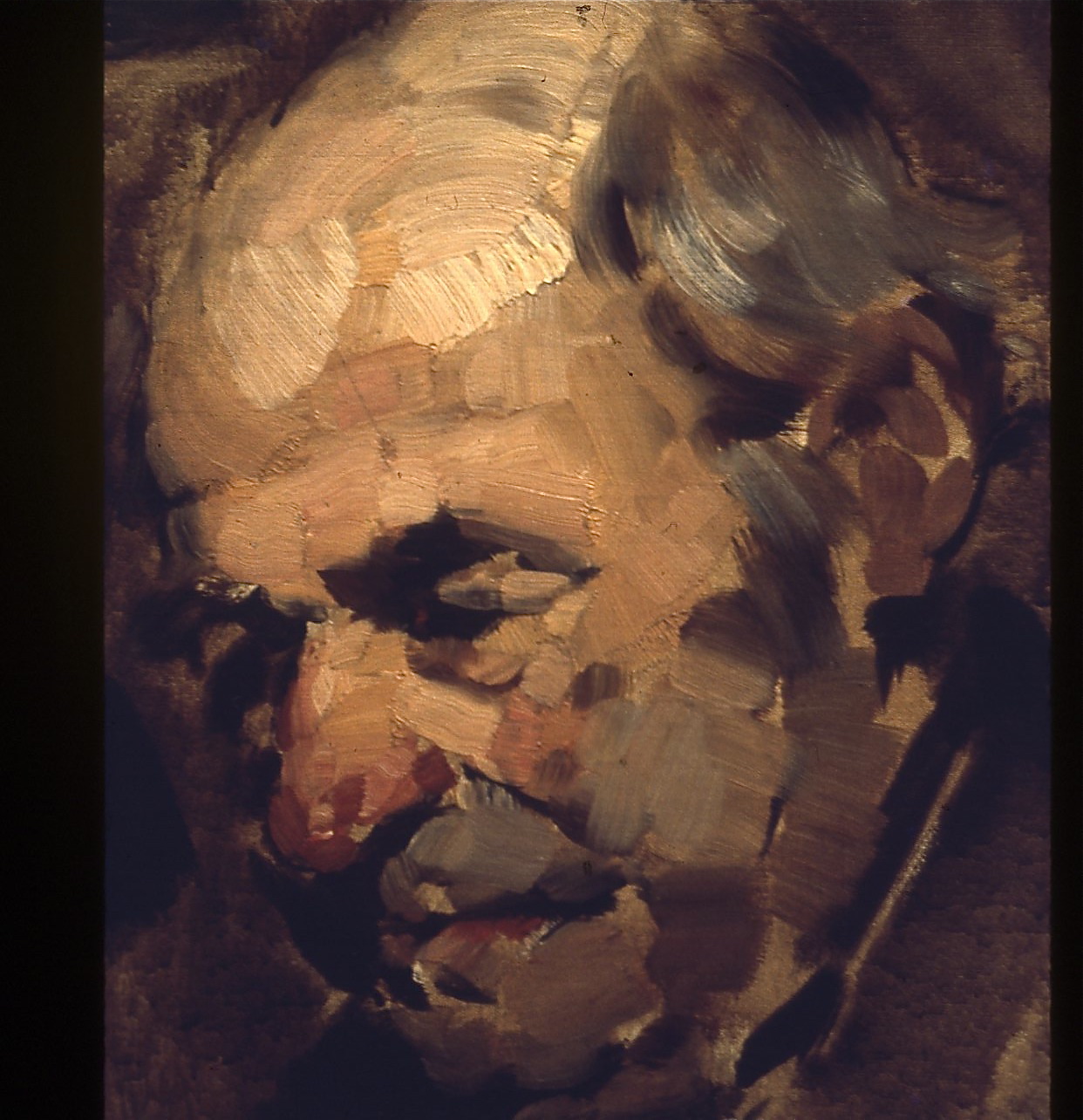

Elena Zolotnitsky makes painting seem easy; her pigment, alchemical. Subtle and sensitive, yet direct and confident. The sharp edge of the hair contrasting the skin shapes and values is intriguing and amplifies the soft features of the character.

Oh, you know I had to have Sargent in here. I don’t see this one reproduced that often and I’m guessing that most critics fail to recognize it’s strength. Besides the shift of cool to warm color in the chest, the passage of note is the edge of the cowl that rolls quickly into the shadow along the left side of his head giving it sculptural depth.

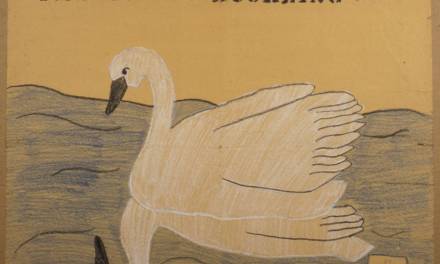

I saw this original at a popular show of JW Waterhouse’s work. I wasn’t familiar with it because, again, I don’t think non-painters understand it’s strength. The original piece glows with the gold, but I love the way the uraeus ( a sacred serpent of Egyptian deities ) of her crown just captures the edge of light, leaving the face in complete shadow.

This is by Gustav Klimt. Stunningly rendered; utter control of every detail. I love the two tiny pink reflections on her forehead. I say tiny because if you’ve never seen this piece in person, you wouldn’t know that it’s smaller than 5×7 inches. Inches.

Thanks for taking the time to do this posting, Greg! I would suggest an addendum to your comment for the Waterhouse painting. I wouldn't describe the face as in “full shadow”, as the bounce or fill lighting from the dress illuminates it just enough to fully describe the forms.

Thanks!

Yes! Quite right, Dianne! Its really just shadow with fill or bounce light.

Thanks!

I did practice with portrait drawing myself; in addition to owning the Famous Artists book on the subject, it's covered in drawing basics of Betty Edwards' famous work “Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain”. I agree that working with the portrait is a good way of learning and of sharpening your skills.

Hi,

This is a really good post. Must admit that you are among the best bloggers I have read. Thanks for posting this informative article.

I hope it would really helpful for my link Portrait Painting

Thanks again

راه اندازي کسب و کار

موفقيت مالي

آموزش هيپنوتيزم

آموزش خود هيپنوتيزم

چگونه هيپنوتيزم کنيم

هيپنوتيزم درماني

کسب در آمد از طريق اينترنت

کسب و کار اينترنتي

کسب در آمد از اينترنت

کسب در آمد در منزل

روش هاي کسب در آمد

کسب در آمد اينترنتي

راههاي کسب در آمد

راه هاي کسب در آمد

راز موفقيت چيست

موفقيت چيست

راه هاي موفقيت در زندگي

راه هاي رسيدن به موفقيت

راه موفقيت

راههاي موفقيت

راه هاي موفقيت

روانشناسي موفقيت

عوامل حياتي موفقيت

عوامل کليدي موفقيت

عوامل موفقيت

راه اندازي کسب و کار

موفقيت مالي

آموزش هيپنوتيزم

آموزش خود هيپنوتيزم

چگونه هيپنوتيزم کنيم

هيپنوتيزم درماني

کسب در آمد از طريق اينترنت

کسب و کار اينترنتي

کسب در آمد از اينترنت

کسب در آمد در منزل

روش هاي کسب در آمد

کسب در آمد اينترنتي

راههاي کسب در آمد

راه هاي کسب در آمد

راز موفقيت چيست

موفقيت چيست

راه هاي موفقيت در زندگي

راه هاي رسيدن به موفقيت

راه موفقيت