I recently rediscovered the beautiful practicality of Daniel Coyle’s The Little Book of Talent, 52 Tips For Improving Your Skills. It’s small, engrossing, and powerful. It’s the kind of book you’ll return to over and over again because it’s written so succinctly, so clearly that it verges on a poetic version of training principles.

The fifty-two tips aren’t principles of art, or how to mix color or compose a painting, but if you read with the idea of training to become a better artist in mind, each page reveals a thought process that can be easily applied to your skills.

Daniel collects his research, rearranges it, and presents each principle edited down to its most direct approach. One can access the studies where this research originates as he gives titles and links for further reading, but I find that the plain language helps to get the points across quickly. It reminds me of painting, where two or three strokes placed well can do the work of twenty. Detail is implied, not brow-beaten.

My students are reading it now and I plan to use it as part of my class structure for Smarter Art School. Below are fifteen of my favorites from the book, adjusted to make sense for an artist. There are so many more, but once you see how these fifteen work with regard to painting, I think you’ll be fascinated. (numbers corollate to Coyle’s tips.)

4. Keep notes.

Write down ideas before they fade. Do thumbnails of even your most ambitious ideas. Test it on paper. Write out your concepts if you feel you’re not able to express it in a drawing. This prepares you for later when you’re ready. Get them down quickly to capture their essence.

Neil Gaiman said that he had the idea for the The Graveyard Book early on in his writing career, but knew he didn’t have the skills to capture it. Though he recognized that the idea was solid, Gaiman waited until he developed his skills further to write it.

5. Be willing to be stupid.

Failure is not a problem when skills are on the line. Failure is necessary as it builds on information the brain needs. We all flounder with this because we’re taught that looking stupid means stupid. But the research tells a different story. Many children have an immunity for looking and feeling foolish and they develop ahead of their peers in their goals when they can let go of embarrassment and pay attention to their progress.

6. Spartan environments.

Work no matter the comfort level, or tools, or conditions. I’ve often dreamed of my ultimate studio space. A place that was so perfect for light and energy that work would come easily. Yet, my studios have always been a bedroom commandeered for work. Small rooms with just enough space to work and be surrounded by equipment and books.

I work that way even now, though my bedrooms have enlarged somewhat. And I’ve realized that over the years I’ve built an environment of efficiency. A place for nothing but work. A place with no reason not to achieve. After reading the studies that show how creativity thrives when it’s limited, I understood. I’d been honing my skills to work in whatever condition was necessary to get the work completed. The environment that we create in shouldn’t matter.

(The fun part about this is that I’ve put in so much training over the decades that now I know how to get to work. So it may just be time for that great studio…)

7. Hard skills, soft skills.

Learn to draw well. Drawing is the hard skill necessary before painting. It’s difficult at first, sure. That’s one reason why it’s called a hard skill. But go through the agony of learning to draw well anyway. Understand the principles. Get them locked in. Just do it. Just sit down and learn it.

Everything of value in art comes from that point. That skill.

When things start to come apart, you can always rely on your drawing skills to pull it together. Use the skill to change on the fly, to create better ideas. Sometimes, when in a meeting or on a creative team, things get muddy, fall apart, or the client doesn’t like what’s being presented. Thinking on your feet is bolstered by your ability to visualize and show what the concept is.

London cab drivers must go through the process of learning every street, intersection, alleyway, thoroughfare, avenue, nook and cranny in a three mile radius of Charing Cross Station. There are 25,000 of them. They call it, The Knowledge, and it can take three years to master.

Drawing, for us, is The Skill. Get it. Keep it. Use it. Continue training it.

11. Prodigy myth.

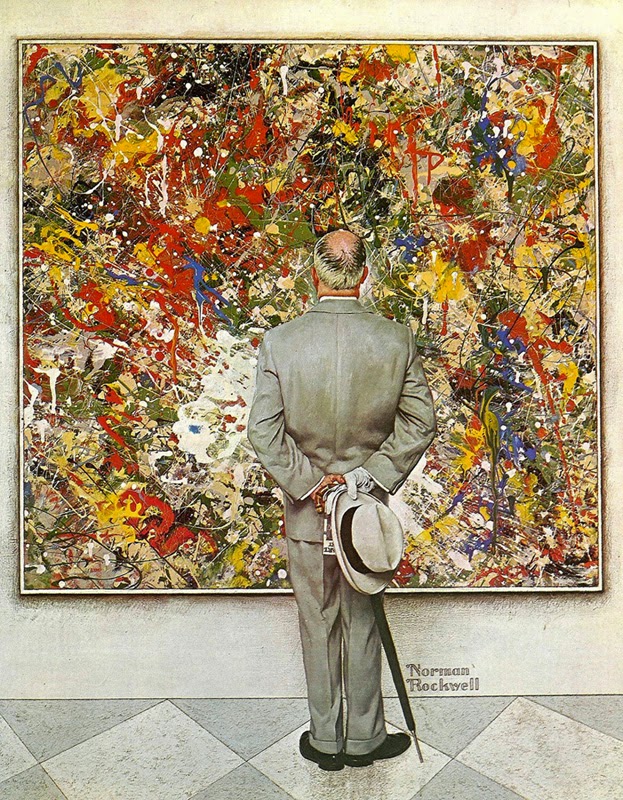

As artists we may just suffer the most from this idea. The myth that you’re either gifted or screwed when it comes to being an artist. Forget all the people “trying their hand” at making art, this is the one overwhelming attitude that pervades all of the industry and will prove whether those people succeed or not. The search continues for the next so-and-so, the next whomever, who will out-genius everyone else.

But that’s not where the research is. The science continues to pour in: Artists are built. Not born.

15. Chunking: break down moves.

To gain better skills, especially in painting, the steps must be broken down and understood, a principle at a time, expressing and experimenting with each, such as, perspective, value, shape, depth, etc.

Break down composition to it’s basics. Build an idea in pieces. Build your technique in pieces. Then combine them in chunks to work your way back to being able to control an idea from thumbnail sketch to finished piece.

17. Embrace struggle.

Embrace failure. (See item number 4.) Failure is part of the struggle. When everyone talks about how an artist struggled along the way to success, at which point do they forget that having a gift is supposed to take that struggle out of the equation? People are amazed by how a person with talent doesn’t struggle. They merely achieve. Sometimes instantaneously.

Get over it. Struggle is the key. We often complain about how much ‘work’ something is to achieve. Why are we so averse to working? Work is the process. Work is the struggle. Work is the point. Embrace it.

20. Train alone.

I used to think I was some kind of abomination of humanity because I enjoy being alone. My alone time is primarily for work or research. When you’re onto an idea, any disruption can steer you away from reaching a point or defining a concept.

Other times I attempt to research something on the web and get caught by email. I might even forget what I was originally trying to find. Many people are distracted by Facebook or other social media sites. (Keeping Facebook ‘on’ is not being alone.) Research shows that creatives who achieve their visions tend to work long hours by themselves.

Paint alone. Spend time alone. Illustrators are fine by themselves. You’re not weird. Just focused.

26. Slow down.

When I first started painting seriously, I painted with the final layer, the one on top, in mind. How did I want that to look? I wanted strokes that looked like the painters I loved. I wanted that kind of control. I knew if I had that control I could paint however and whatever I wanted. So I mimicked the kind of strokes I loved by placing them slowly on the top layer. I designed where I wanted them to go, how they would shape the form of something in the painting, and then placed them with great care.

Slow is the secret.

Slow down and make deliberate moves. Study masters. Slowly copy their finish levels. Slow brushwork leads to fast. Speed comes from slow-motion mimicry.

38. Stop before fatigue.

Work late, but stop just before you’re finished. Leave something for the next session that pulls you back to the work. Writers do this all the time. When finished for the session or the day, they leave something that they’re eager to get down on paper. This excitement pulls them back to the work, to the idea, to the writing the next day.

Leave something to come back to in your work. If the painting needs attention in a certain area, leave the entire area for the next session. It’s a powerful magnet.

39. Practice after performances.

Just finished a piece for a job, even a big one? Get right back to painting after it. Plan your next piece, or even have it ready to work on. You’re moving along now at work awareness and speed, so push it into your personal work. This is where you can make amazing progress.

Many of my illustrator friends work on multiple jobs at once, juggling between final strokes for this job, conceptualizing that job, working sketches for several more. This is the life of an illustrator, and survival through work, is key.

Move through multiple jobs concurrently. This helps you shift between focuses. Coyle’s brilliant book speaks about this in more depth. (see tip 49)

43. Embrace repetition.

Repeat successes. Follow achievements with similar approaches. Don’t allow your portfolio to shift focus when presenting it. A succinct voice helps people remember your work.

Look through your portfolio. It should have a focused approach. A scattered portfolio telegraphs one thing to an art director: scattered mind, scattered effort. If you have multiple styles or want to try multiple techniques in the business, then develop a portfolio for each (or continually modify one book for separate clients). Yes, you read that. Multiple styles each demand their own focus. Lotta work, isn’t it? Welcome to the process.

Besides, if you can do several styles well, you’ll get to branch out from there once you have their attention.

44. Blue collar mindset.

Get to work. No matter the grief, confusion, attitude. Your attitude will change once you are drawing. Inspiration is for sissies. Professionals work no matter what, no matter when, where, how. Routine is effective.

49. Defocus to refocus.

Daniel’s book basically says, if you get stuck, make a shift. As an artist, if you work and work and results are bad and getting worse, it’s because of your attention. Change tack. Shift to a different task. Defocus to refocus.

Taking a break is fine, but try to stay with the energy of creating. (One designer’s tack is to move from his graphic work to playing an instrument.) You’re either off-target, distracted, or unfocused. Shifting allows you to refresh and gain perspective. Reenergize. (of course, if you really need to get away, perhaps you need sleep! Lots of research coming in now about that, too.)

51. Protect your goals.

This one may sound kinda nutty, but you’ve got to be protective of your deep-seated, what-I-really-want-to-do-is ideas. RARELY tell anyone about your most secret desire for a creative thing. Keep it inside. Work to create it. The effort stays alive within you and wants to come out someday in it’s best form. The one you’ve always known you can do.

Telling people takes the effort away and your brain feels accomplished by their positive reaction. And many times an idea laughed at by someone who knows nothing about the creative process can destroy a good idea. I’ve had many students get stalled for weeks because they took someone’s opinion to heart too early.

Only to your most trusted friends, or colleagues, can you share a shred of an idea and only if you know they can be discreet. (No family either.)

And you hold their goals close, as a gift to them. Payin’ it forward.

Coyle’s book is a template for the kind of book I see for my Ten Things… book about painting. Practical, direct, clear.

Speaking of that, Daniel’s book, The Talent Code is a must-read for every creative. And have a look at his website, danielcoyle.com for a lot more about achieving the skills you want. In The Little Book of Talent, he’s also got a list of other author works you’ll find fascinating as well. That list alone will change your artistic life.

Let me know if this helps.

Sounds like a book to get hold off. Thanks Greg

Great advices as always!!!

Fantástico Greg. Ensinamentos que quero colocar em pratica! Obrigado.

Great advice. Can’t wait till your Ten things about painting book comes out. I’m an introvert, so the working alone thing is right up my alley.

Hey Gregg! Thanks for the great article. Fine hat tip to the “Talent Code”! Greetings from Hawaii!

Hey Gregg! Thanks for the great article. Fine hat tip to the “Talent Code”! Greetings from Hawaii!

Thank you Greg what you’ve written here are treasures They are not fashioned by trendy advices but written timeless words of wisdom.