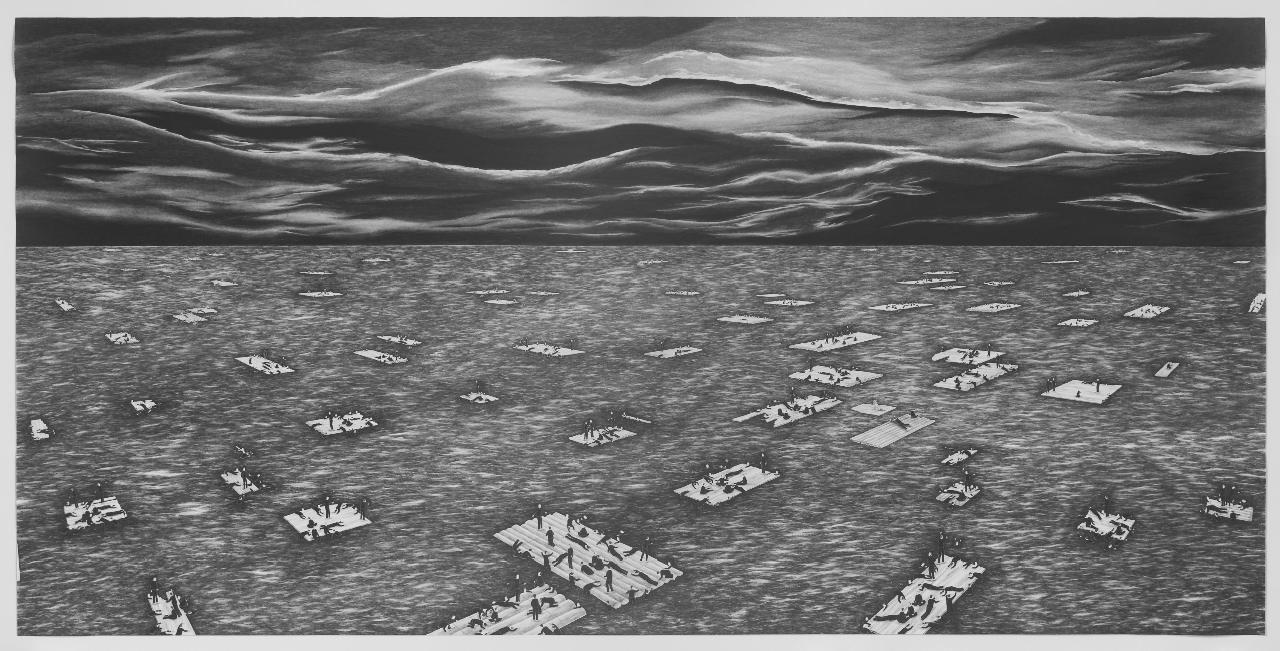

Robyn O’Neil, “Masses and masses rove a darkened pool; never is there laughter on this ship of fools.”

The post below was written over eight years ago (with some edits that I did recently) and was inspired by Joan Didion’s essay, “Why I Write.” At that time, I was living in East Williamsburg, Brooklyn. I had a studio in Bushwick. I was teaching an illustration course at the School of Visual Arts, in New York City, and I was also enrolled in an Intro to Fiction Writing class at NYU. I don’t remember why I chose to write about “why I draw” aside from the fact that the feelings which came up as I struggled to write felt very similar to the feelings that surfaced when I drew pictures.

~

Sometimes when I’m sitting in class and listening to my professor talk about the process of writing my mind begins to drift; not in a way where I stop listening to what he’s saying, but I start to align his words alongside my craft of drawing. I have a terrible time with labels, assigning and boxing things neatly (or not-) into some kind of container and then giving it a name. You’ll notice that I switch between the words, art, craft, illustration, design, and drawing in many of my posts — and when I do, I think it’s because I see them more each time as being similar to one another. Although there are people who I’m sure can provide an explanation on how and why these disciplines differ from each other, I don’t care so much anymore.

When I was 13 years old, I clearly remember saying out loud that I wanted to draw for a living. Back then, I had no clue what I was talking about because I didn’t know anyone who made money from their drawings. When we moved to Canada, my father worked in a factory and my mother did data entry at her first and only job for over forty years. I was taught that hard work and having a job that paid regularly was something to aspire towards. My family has never truly lived beyond the need to manage the necessities of life. And so, our lives were very routine with not many extras or surprises: no dinners out, no family vacations, and no elaborate gift giving (food became an expression of love and validation — my mom is a brilliant baker, which explains why I love cake so much). As a kid, drawing allowed me access into new worlds; I was Simon and although the things I drew didn’t come true, they did make my life seem less ordinary.

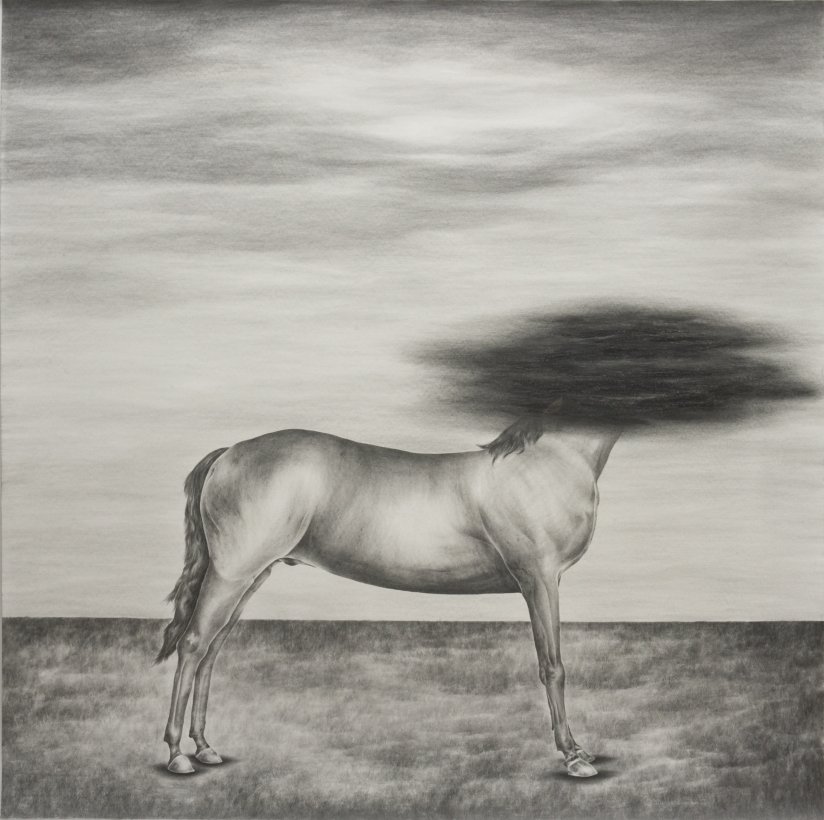

Robyn O’Neil, “A Disharmony.”

I loved the way drawing made me feel. Even as a child I could sense my love for it went much deeper than loving cake and ice cream, watching cartoons, or going to the mall. My parents saw drawing as a hobby, and supported it in a way where my father bought me comic books and my mother brought home blank sheets of paper from work, the kind that had holes along the sides and was attached to each other with perforated edges like toilet paper so you could tear the paper neatly along these seams. In high school I had several conversations with my worried parents (as I’m sure many teenagers around the world have had as well) about how I should choose a course of study that was more appropriate and practical, one that would take care of my future self the way that drawing wouldn’t.

Eventually the fear that sprung from this uncertainty found a comfortable nook in my mind from where it would occasionally whisper cruel things to me. There were moments when I thought I would give up drawing. In my third year of art college, I nearly dropped out even before the semester began. I wanted to move out of my parents’ home. Things were very bad between my father and I — it’s the familiar story of a father and son whose differing life views creates a chasm between them. Having worked since I was a child, I’d felt a deep sense of autonomy growing up because nearly all of the significant purchases in my life were either handed down to me, or I’d paid for them using my own money. In my mind I believed that I was capable of taking care of myself even though in hindsight I know this now to be untrue. During that time, I was working at a clothing factory in a suburb of Toronto to save up enough money to move out. Had I done so, I have no clue where I would be now. Fortunately for my sake I snapped out of this delusion and was persuaded by my brother and sister to stay in school for another two years. My brother told me that if I still felt this way after I graduated then I should make a decision then — I moved out shortly after graduation.

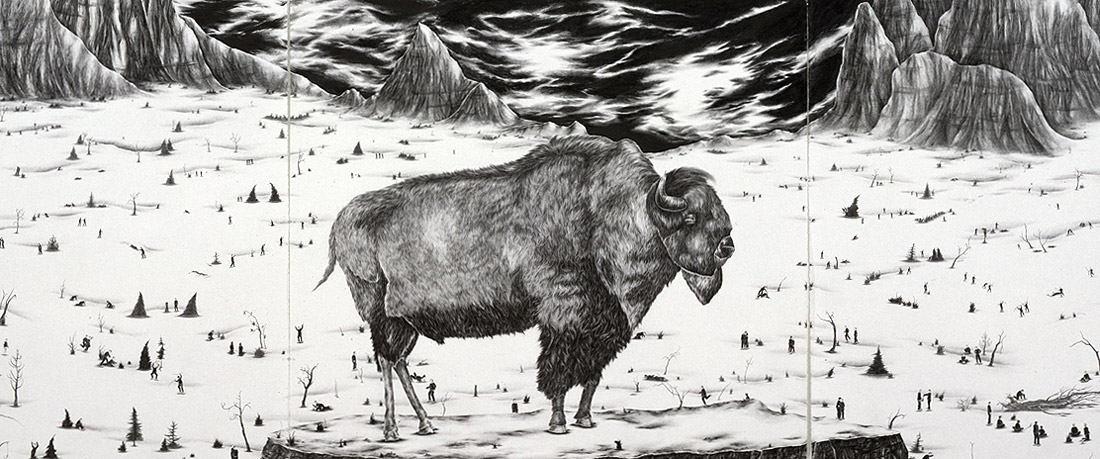

Robyn O’Neil, “The Climate.”

It was around this time when I probably drew more fiercely than ever because I was deeply convinced that I had no other choice than to draw. I didn’t know how to do anything else, I had no skills, I didn’t have much money, no savings or trust fund, and I couldn’t rely on my parents or siblings for a handout. In a way, I cast all of my hopes and frustrations into drawing, wanting so badly for it to lift me out of the space that I was in.

And so, I drew —

I sometimes look at my drawings and wonder if they’re good, or not. I understand that if the drawing’s been commissioned by someone else that there are reasons that make it successful; that in addition to the aesthetics, the drawing must communicate an idea, and appeal to an audience. It’s commercial art after all. I believe this, and I teach this to my students: content is paramount. But when I distance myself from my work and really stare at it, the parts that aren’t so good begin to reveal themselves to me. I’ve always fantasized about being a great artist, like the ones whose books I keep on my shelf. They are the ones who can manage shape and line in such a way that they seem to have exclusivity to use them. They know how to use colours in such nuanced ways that they could’ve been the only ones who mixed them. But despite how amazing their work might be to me, I’m sure for many of them their level of greatness didn’t come easily, or quickly either.

I recently opened up Charley Harper’s book, the one that was put together by Todd Oldham, and it makes me feel good because the pictures in it reminds me of why I draw. The photos of Harper’s work span his entire lifetime, homing in on the figurative and narrative aspect of drawing, it’s the drawing itself that is the content. The way in which he relates colour to one another is magical and the restraint that he holds when rendering details convinces me that there’s a reason and a place for every mark that he puts down. And even though he’s an artist who I revere whose pictures I’ve elevated way above my own, I’m learning to appreciate the work that he’s done as just that, work that he has done. I try to remind myself now of the importance of the act of drawing, drawing for drawing’s sake, not drawing for money’s sake, nor for the sake of fame, or for the sake of trying to be like someone else. These things feel less important to me.

And so I draw —

I draw because I enjoy moving the paint around on the page, and the stylus on the tablet. I enjoy mixing colours and arranging them next to each other to create patterns. I enjoy making marks on the pages and allowing them to enfold into each other, and then break apart into something figurative or abstract. I draw because there are things I want to say that I don’t know how to express through words, or actions. I draw because I want to be seen. I draw because when I do, the world around me falls away.

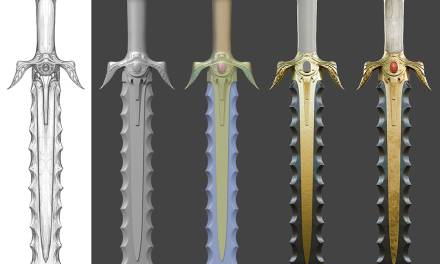

Robyn O’Neil, “A Dismantling.”

In continuing to share the daily rituals of artists, below are some by Robyn O’Neil. I’ve been fan-boying over Robyn’s work since 2005 when I came across it in the book Vitamin D: New Perspectives in Drawing, by Emma Dexter. I was swallowed up by her beautifully stark and ruminative graphite landscapes. Years later I stumbled upon her podcast “Me Reading Stuff.” Robyn was reciting Mary Oliver’s poem, “Wild Geese.” I’d been obsessed with it months before, and like any song or poem I love, I’d committed it to memory. And so after a few minutes of mental debate, I emailed her, in proper fan-boy fashion to tell her how great she is.

Robyn O’Neil, “As Ye the sinister / Creep and feign / Those once held / Become those now slain.”

M: Do you perform any rituals in your daily life?

RO: I have many. The first is pretty unoriginal, but my morning coffee is vital. I can’t even imagine a work day without it. I can’t even partake in caffeine due to a pretty serious heart condition, so it’s more the ritual of a hot drink, not the need for a jolt. I drink lots of it all day long.

An even more important ritual is my nightly dusk-time walks sans cell phone. Sometimes they’re only five minutes, other times they’re hours long. But I don’t like living through a day without a walk.

I also drink a gallon and a half of water a day. And I feel the need to drink water about every five minutes. I go crazy when I can’t get to water immediately.

M: If you do perform rituals, do you do this regularly or are they dependent on other situations that occur alongside of it? If the latter, can you give an example(s) of a moment(s) in your life that caused you to perform rituals?

RO: A lot of my rituals are dependent on specific situations. For instance, traveling brings about several important rituals. In fact, I am even more in need of rituals when I’m away from home because I really don’t like being away from home. At all.

The second I get through security at the airport, I buy a huge bottle of water. I have a deep fear of not having water accessible to me. Once I’m on the plane, I have these things ready for me: crocheting supplies, at least one book, at least one magazine, and stationary to write letters and/or postcards. I seriously can’t get on a plane without these things. And I always need an aisle seat on the right side of the plane. When I get settled in my hotel room, I immediately go to a grocery store. The staples are: tons of bottled water, bananas, apples, and saltine crackers.

M: Do rituals and habits differ to you or are they the same? If they’re different then how are they different?

RO: In my opinion, rituals have a sacredness and thoughtfulness to them. Habits are thoughtless. Habits are behaviors that aren’t quite as self-examined as rituals, but they can become rituals. I have quite a few of both rituals and habits.

M: How do you begin your day? Is it more or less the same each day, or does it change?

RO: I wish I took a shower first, but I immediately make a huge decaf americano after “zombie walking” from my bedroom to my studio (which is down the hallway). I like to work for an hour (I set the alarm on my phone) before eating or showering. It’s my favorite part of the day. I like the fuzziness of my brain during that first hour.

M: Do your rituals affect or align with your creativity? If so, then how?

RO: Another important studio ritual I have been doing since as far back as I can remember involves tv shows and movies. Since I make large, time-consuming drawings, my work sessions are dependent on tv shows and movies. For instance, I will make a deal with myself while working that I will not move away from the drawing until, say, I get finished with two Dawson’s Creek episodes. Or I won’t take a bathroom break until the Jeffrey Dahmer documentary is finished. All of my drawings are STRONGLY dependent on watching tv and movies. I have never made a piece without the tv being on.

M: When you begin a project do you prepare in a specific way? If so, then how?

RO: I have these basic marbled composition notebook that I’ve been using since I was in high school. I will not use any other brand but these. And before I start a drawing, I make several thumbnail sketches to help me decide on a composition. Once I pick the best option, I sketch in the basics and begin work.

Robyn O’Neil, “Suffocation Bed.”

M: When you come up against creative block or procrastination, how to you move alongside, or through it?

RO: I honestly don’t often have this kind of issue very often. My biggest problem is forcing myself to not work. I have a bit of addiction to my work, and that’s not good either. My composition notebooks serve as a constant mind-dump. So, while I’m tied to a drawing that may take up to three full years, I’m making notes all day, every day about what I want to make next. By the time I’m finally done with whatever my large project is, I have hundreds of ideas to sort through. Granted, most of them are terrible ideas, but there are always at least a few I can use. So basically, I’m constantly catching up with myself since my drawings take so long to complete.

M: Are there certain tools that you use to create your work – specific brands, or stores that you shop at? Is there is a reason(s) why you do this?

RO: Until very recently, all I ever used to make my work was one specific Pentel mechanical pencil, one specific retractable eraser (General’s Factis Mechanical Eraser), and one smudge stump (also known as a tortillion.) My smudge stump was given to me by my mom when I was in 7th grade. I’ve used the same one for almost 30 years. I could not make a drawing without it.

Recent Comments