This month I’m returning to my series “Turning Points” which looks at some of the Brand Name Master Artists with clearer eyes at their careers. These one-named artists (you know, the Muchas, the DaVincis, the Caravaggios, the rest of the ninja turtles) have become so ingrained in our consciousness that we can’t see them clearly, as people, or as artists. This year, when we are all struggling for so many reasons, I think it is the most important time to remember that they struggled as well, and see their lives in perspective. Many were not any more famous in their own time than artists who write for this blog — some much less so. Certainly thousands fewer people recognized their work by name than artists on instagram today. Most were forgotten for a long time after their death — and only chance or another artist saved them from complete obscurity. They doubted themselves. They had personal and career crises. They failed. They got back up and made art again. Just as well all do.

There are so many harmful myths about being an artist. We have so many unreasonable goals as creative people. It’s critical to look at the entire journey of these most famous artists, not just through the lens of how we see them in modern times, as coherent brand names, but as humans.

Last time we talked about the incredible stroke of luck that started Mucha’s career, and how his chance rediscovery changed the whole visual culture of the 1960s. This month we’re talking about Botticelli and the self-doubt and pandemic-fueled public outcry that destroyed his work.

Botticelli lived in Florence from 1446 to 1510. A trip to Rome to work on the Sistine Chapel may have been as far as he ever got from where he was born. He was not a traveler. But what a great time to be an artist in Florence! Although “The Renaissance” is a creation mostly of an artist who was more skilled in PR than in painting, Giorgio Vasari, there’s no denying there was a perfect storm of a ruling family (the Medicis) who liked to show off their money via art, setting the trend for the rest of the city’s monied class, combined with an established model of large artist studios constantly accepting new apprentices, plus the added bonus of the Catholic Church’s policy of indulgences, where you donated money as gifts of art or architecture in return for a guarantee that your sins would be forgiven. And as I’ve heard one art historian say, the amount of religious art in the Renaissance wasn’t a sign of how pious the patrons were, but actually a sign of how much sinning was going on.

So Botticelli was dropped into this hotbed of Florentine art and commerce. He was apprenticed to a goldsmith first (no surprise, if you look at his delicacy of detail and the ornamentation of gold all over his works) but eventually changed his mind and ended up in both Filippo Lippi’s studio and later Andrea del Verrochio’s studio as a painting apprentice. He painted alongside another apprentice, Leonardo DaVinci. I’m sure they had at least a healthy competition, as any star students would have.

But before we get any further, let’s point out that this master, this brand name we revere…is not the artist’s actual name. Botticelli means “Little Barrel” – we’re not totally sure why he was called that, but some sources say his big brother was called Big Barrel, and thus he was called Little Barrel. How would you feel if your work was immortalized under the silly name your drinking buddies called you? Poor guy.

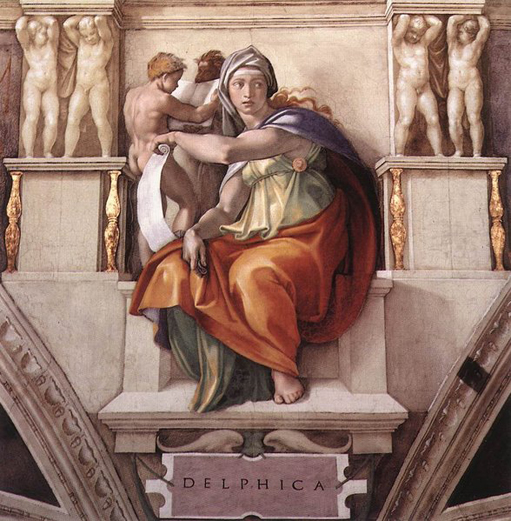

Anyway, as I said above, there were only a few categories you could work in during those times. You could make pious religious art that rich people donated to churches or religious orders commissioned themselves from donations from rich people:

You could paint portraits of the rich people, and their wives and official girlfriends (remember those indulgences were well-earned):

And then you could paint commissions of what rich folks wanted in their homes, or wanted to give as gifts to be hung in other people’s homes (paintings were a big marriage gift of the day). And those scenes were encouraged to be decidedly less pious. Now remember, “Renaissance” means “rebirth” – the Italian word Vasari actually used was “Rinascita” – and what was it a rebirth of? Ancient Greek and Roman learning, that reappeared in Italy via both through the ground and through rich folks sending book hunters out to search for books to make their libraries more impressive (a fascinating story in itself, I recommend the book The Swerve for more on that). So there was a huge interest in depicting the Greek and Roman myths. And since these were pictures meant for the home, and mostly private viewing by the owner and his guests, art could push the envelope. And what did rich Italian guys want in their man caves? Beautiful, scantily-clad women. And some scantily-clad men as well. And thus, sex appeal crept its way into Botticelli’s paintings.

Tasteful sex appeal, but still pretty racy stuff for the times. And Botticelli, who had always painted such beautiful Madonnas, was the obvious choice for painting beautiful women. Now I’m going to refrain from heading down the side conversation about the history of the nude in art and how it’s often been a vehicle for “proper” sex appeal. (I have been savoring Mary Beard’s new documentary and I’ll definitely be doing a future MC article on it, so for now we’ll stay on track with Botticelli.)

Now there’s a lot of debate about how much Botticelli was responsible for the pagan and sexy themes and how much he was forced into it by his commissioners, but we’re all familiar with what that mental debate looks like: Am I making what I want to make, or am I making what I know will sell? At some point it’s nearly impossible to tease out all the commercial influences on an artist’s work. The 1400s were no different.

And then a bad plague came through town. And political unrest (the Medicis and the Prince of France, who controlled Naples, were fighting, and the city was under threat of siege). And in the fear and anger and uncertainty, the people of Florence were looking for somewhere to lay the blame. And the Dominican priest and fiery orator Girolamo Savonarola was ready to give them answers. Through a campaign of public sermons he convinced the “good” people of Florence that the Medicis and their pagan ideals and their non-religious art and the corruption in the Catholic Church was to blame. God was punishing Florence with the plague and the siege and the only way to win back God’s favor was to burn all the non-pious art, books, and symbols of luxury like mirrors and jewelry. Even many religious paintings that weren’t of the “right” themes were destroyed. Savonarola started a mob, who wore white shirts and were called his “little angels” and “Piagnoni” (weepers), and they dragged hundreds of irreplaceable books (remember this was before mass production of books) and pieces of art out to the main squares of Florence and burnt them. The largest happened in 1497 and was known as the Bonfire of the Vanities. Artists were forced to renounce their challenged work and burn it, pledge to never make “sinful” art again or risk their studios being burnt and potentially losing their lives. Some artists went along with what they had to do to save themselves, and some were also convinced of the righteousness of Savonarola’s cause and went along willingly.

Botticelli was one of those who were convinced. He repudiated his non-pious works, and burnt everything that wasn’t safely protected in a house that Savonarola’s mobs couldn’t force their way into. The only reason we have The Birth of Venus and La Primavera is because they were kept at Medici properties outside Florence. Who knows what masterpieces were lost?

And then, as always happened, the mob burned itself out and the backlash began. Once the plague passed and the threat of siege ended the city woke up. They got tired of witch hunts and burning. Except for one more. Someone had to be to blame once again. Savonarola himself was ultimately burned alive in the very spot the Bonfire of the Vanities had taken place.

This was all too much for Botticelli. I can only imagine the layers of regrets and destruction must have sent him into what we would call a nervous breakdown today.

I was reminded of this painting – one that isn’t nearly as pleasant to remember as Botticelli’s beautiful women – by a recent article in the New Yorker by Jerry Saltz. He calls it the saddest picture he has ever seen, and I can’t disagree with him. It just oozes regret. We’re not sure if Botticelli regretted making the paintings or burning them more, but either way, he was a broken man after Savonarola’s campaign of terror ended. He never painted again, and a few devoted patrons kept him alive by their charity alone. For the next 300+ years, no one really cared about Botticelli. Some paintings survived, and were respected enough to be kept in protected collections and museums, but his work was barely known.

Until the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in the 1860s/Victorian Era. Pre-“Raphaelite” refers to Raphael, considered by many to be the last great Renaissance painter, but considered to be the beginning of the end of good painting as far as the PRB was concerned. I don’t want to digress into an article about the PRB, but it wasn’t just about painting beautiful women from fairytales and myths. (Check out this article – it’s quite in-depth but very well organized.) They revered Botticelli’s work, especially Venus and Primavera, and dragged his name into the spotlight. The V&A Museum did a great exhibit a few years back highlighting this and Botticelli’s wider legacy. You can definitely see the direct lines from Botticelli to Waterhouse and Rossetti’s paintings:

Once the Pre-Raphaelites became stars of the art world then the artists they championed did as well. Waterhouse and Botticelli’s stars ascended into the strata of the single-named artist and haven’t left since. There’s something ironic – or maybe just sad – that the works Botticelli is most famous for are the works he publicly repudiated. I like to think after the craze Savonarola incited had passed that Botticelli regretted burning his works more than he regretted painting them in the first place, but we’ll never really know. There’s a few lessons here, especially for us living through 2020, but they’re so tangled up that there’s not one clear pat moral to the story. And that’s the point, really. An artist’s life only looks like a straight path from very far away. Once you get close up there’s all kinds of twists and turns and ups and downs to it. Don’t make the mistake of assuming they aren’t there because you can’t see them in the distance. And don’t think yourself less of an artist because your path is not perfectly straight.

One lesson isn’t too tangled up.

History shows, again and again, that book and art burning is bad. At best, it’s an attack on a symptom of a social complaint, but honestly, it’s just an exercise in power and intimidation for peoples incapable of constructive criticism or honest self reflection and it is theft at a cultural scale.

If someone has a copy of the titular play within a book, ‘The King in Yellow’, they might have a case for book burning. But life isn’t a book of creeping dread and inevitable murderous madness, so… no.

THIS I can wholeheartedly approve of. Burning books and burning art is always the wrong side of history to be on.

It’s an incredibly interesting trip through the centuries. Thank you very much for it, Lauren.

Thanks, that was a very interesting read. I didn’t know he stopped painting all together. I also wonder what great paintings were lost.