My first experience with sculpting animal headed humans came shortly after Colin and I got together. Up until I came along, most of Colin’s sculptures had been made in bronze and steel. I showed up with two kilns, a bunch of tools and about 1000 pounds of water-based (ceramic) clay – as he says, “inspiration in a box… well, a whole lotta boxes.”

Colin had been painting therianthropic creatures for decades. One day I’d been out for several hours and I came back to the studio to find him wrassling with this giant clay giraffe head which he was trying to suspend on a long, skinny, impossibly beautifully arched giraffe neck flowing up from a woman’s torso.

Glancing over his shoulder, he said, “Can you help me out over here?” I looked at what he was doing and said dubiously, “I don’t think clay likes to do that, baby…” But, come to find out (we’ve been learning from each other from the start), it did like to “do that” and we were off and running.

Our first collaborative sculptures were the Chimaera series, life-sized sculptures based on our takes on humanistic creatures from various world myths.

Many years later, I was called to revisit this theme. A young model who’d seem images of the Chimaera series contacted me many times asking if he could pose for sculptures with cat heads. I finally brought him in and we did many sessions exploring different poses – turns out, he made a very good cat! At the same time, a collector of ours stopped by our studio and we had a conversation about the Rakshasa from D&D. He was a huge fan of this Rakshasa and said he thought it would be fun to have a tiger-headed man to accompany another sculpture of ours. Seems the muse was whispering in my ear…

Adapting to New Circumstances

Fast forward to spring 2020 – we’re in the throes of the pandemic, no models can be brought in, all the shows and conventions are canceled, people are feeling uncertain and I think, you know, an animal headed human might be just the thing right now. Light-hearted, fun… I’ll get some practice before I make the life-sized Rakshasa… yeah, this will be cool.

But COVID = no models in the studio = how to deal with getting reference?

I had a number of pictures from my sessions with the model, but usually my process is to rough in the sculpture from photos, then bring the model back in to get additional information and refine details. So I asked, “what is the opportunity here?” Well, the opportunity is I have time to explore all the poses we have accumulated reference for over the years that never made it into sculptures.

Then: “How do I deal with this particular situation?” Well, start with a pose that I had a “roundabout” for (see my post regarding working with models if this doesn’t make sense). Run it through Lightroom and Photoshop to boot up the visual information as best I can – adjust exposure, increase contrast, sharpness and clarity, de-saturate one set of images (sometimes it’s easier to see forms in black and white) and so on until I can glean as much as possible from the pictures.

A great deal of the anatomical information I’d be able to see on a live model is lost in translation through camera and computer, even under the best of photographic circumstances (not being professional photographers)

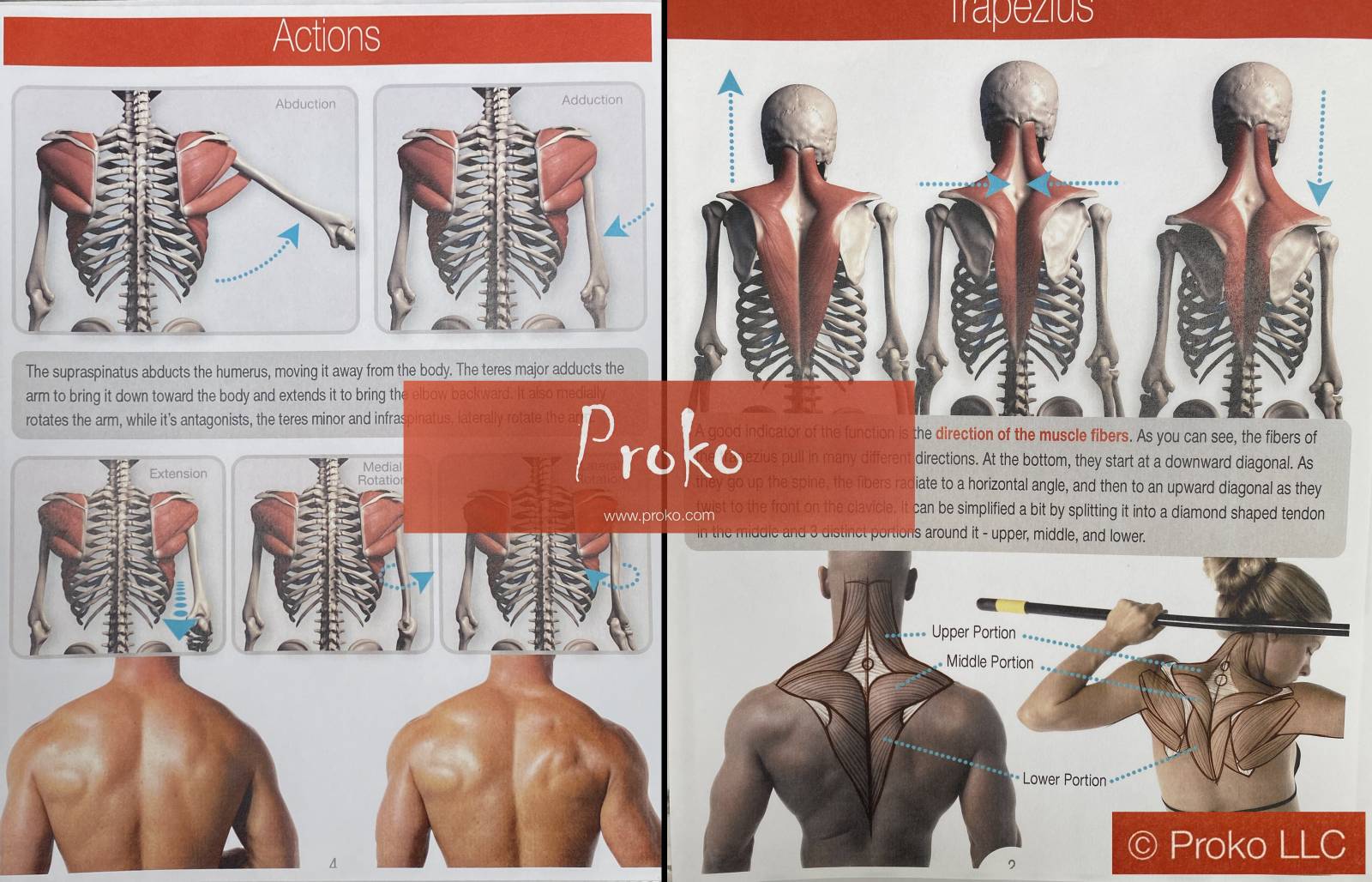

I mentally juxtapose what I know about anatomy over top of the reference images – similar to a 3D version of what you see in these pages from proko.com, as represented in the images on the lower right.

We refer to many different anatomy sources both print and online in our study and also as we work out a sculpture. proko.com is one of our favorite reference sources because in his videos he shows how the muscles stretch and shift in different movements and provides a 3D model of each muscle group so you can see it from various angles – super important for sculpture.

When my reference picture is a bit vague, I am often looking very “hard” at the *lack of information* thinking, “I know this muscle/boney landmark/tendon is there… but the forms are so subtle/nonexistent in the picture…” And invariably, knowing what I’m looking for, I can find the subtlest shift in tone indicting the form. Where I really can’t find the information, I fill in the gaps with what I know “should” be there. I probably wouldn’t be able to use photographic reference effectively without being able to overlay the anatomical information.

One thing this past year has taught me is this: when working with models for sculpture, for poses I like from the get-go, I need to photograph as many angles and details during the initial session as I can, acting as if I won’t have the opportunity to bring my model back in, because sometimes that is the case.

The Blend

With animal headed creatures, the “join” between human and animal is often covered by clothing, thick fur, feathers or other accoutrements. Since the transition in my sculptures is generally visible, I also look at how the muscles in the neck/upper back area work on the animal vs. the human, trying to bring a touch of each so the blend is believable.

With the Tiger Man, even though the blend between human and animal is somewhat obscured by the design motifs and fur, I still exaggerated the musculature to make it seem plausible the muscles could support the weight of the head

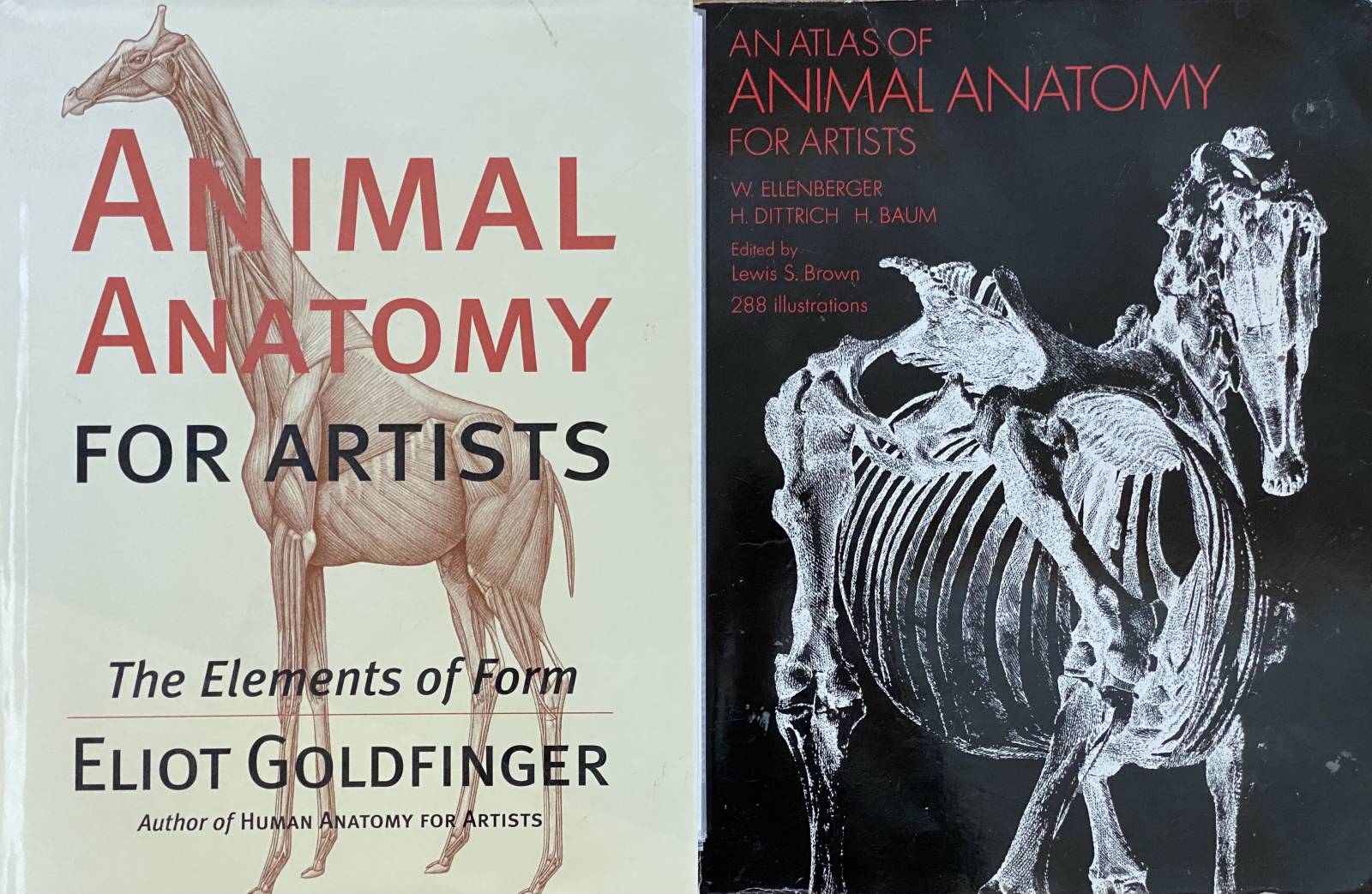

These books are two of our favorite “go to’s” for animal anatomy.

The Sculpting Begins

This 8-minute time lapse shows the full sculpting process on Wolf, one of the figures I’ll be writing about below. Each sculpture in the series was created using this method.

The first character was this little Tiger Guy. He had a particular feeling about him and was so much fun to do that I was curious what other poses/creatures would bring out.

As I’d started with Tiger, I decided to choose the animal heads based on predator/prey animals that exist in similar biomes. Tapir was next… some time ago we’d flown in a model that looked fabulous in reclining poses, many of which I hadn’t been able to use previously. I did a very rudimentary Photoshop mock-up of different animals heads on the body to get a sense of how they felt. When I saw the tapir, it made me laugh, which was just ideal – a sexy lounging tapir? Perfect!

Cape Buffalo and Barasingha then showed up. For some time, I’d been intrigued by this set of poses based on the similarities in how the models were sitting and how the body language naturally set up a story between them. Cape Buffalo ended up having a strong enough presence that he anchors the entire group. Barasingha originally began as a Goral, but after several sessions, it just didn’t look right on this body, so I started over with the deer head, which worked much more effectively. Besides, who wouldn’t love an animal called a “Swamp Deer”?

When I set them together to dry with the Tiger Guy in the background, all kinds of stories started happening in my mind as to what was going on with the group of them. It looked to me like these creatures were having a party in the garden, lounging and sharing stories. Tiger guy looks less than amused at the attention Cape Buffalo is getting (that or he’s hungry)!

As I thought on the Garden Party idea, I added a couple figures doing activities that might happen if you were relaxing in a park on a sunny day – Leo and Boaris. I imagined Boaris reading aloud, as Colin and I frequently do with each other, and Leo sketching images as he listens to the stories. While Boaris was made specifically to interact with Leo, he has ended up being one of the most versatile figures in the group, working well with a number of other figures.

I’ve read about wolves and hyenas in certain areas where naturally they’d be in competition for food, hunting together. With this pair, I wanted there to be a bit more “reaction” in the conversation to elicit further possibility in the storytelling. Indeed, when I posted these pictures, there was a fair amount of conversation regarding what people imagined they were saying to each other.

In creating these sculptures, I originally thought they’d have a “sculptural finish,” something akin to a bronze patina. We chose to use caseins because of their lovely mat quality and, as Colin began painting, the sculptures seemed to dictate a different direction. Each started with the particular base skin tone that complemented the animal head color and progressed from there.

In a medium that is by nature quite static, I find the idea of having a group of sculptures that viewers can “play with” intriguing. They can be arranged in various numbers and positions for different effect, creating the sense that the piece as a whole can continually evolve. It also encourages viewing of the individual sculptures from many angles, not just the front view or “money shot,” something we feel is important to consider in sculpture concept.

Even whimsical artwork can be a source of “serious play.” Given the times we are living through, an inspiring metaphorical undercurrent I see represented here is the predator and prey animals, natural “enemies” in the real world, getting along and enjoying each other’s company by talking amicably, playing and sharing stories. Perhaps we’d all do well to learn a little from them.

Keep creating!

These are so amazing individually and as a group or groups! So fun and mysterious..Thank you for sharing!

Thanks Brian! Delighted you enjoyed seeing them as much as I enjoyed making them. <3

Excellent work on these and such an intriguing mix, set up and idea.

The Cape Buffalo and Hyena are def favourites here, so much character in all of them.

Thanks for sharing the process!

Thanks Nico – so happy you enjoyed seeing the process. And yes, I love Cape Buffalo and Hyena, but I have to say Tapir is also a favorite of mine.:) On another topic, I just wanted to say thanks. I noticed that you comment on many of the articles by various contributors here on Muddy Colors. We all so appreciate the feedback.