Time for another installment of a series I’m calling Turning Points, but could just as easily be called Hindsight is Blind (or at least awful rose-colored), which is all about looking back at artists that are pretty universally considered masters today — but trying to look past the myth and actually consider the struggles they had in their own time. I think it’s really important for artists today to understand that everyone struggles. Even the masters. Especially the masters — the entire concept of a “master” artist very often only happens after their death, and almost always by so much chance (and accidental curatorial choice) it’s terrifying. I guess I could also call this series “Being considered a Master After Your Death Doesn’t Make You Happy While You’re Living Through It” but that’s a little long.

You can read these in any order, but so far we have talked about:

and

Today we’re going to talk to John Singer Sargent and how his fame (and famous clients) very nearly drove him away from painting entirely.

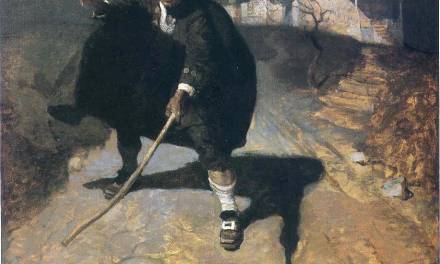

I’m not going to repeat his biographical info, especially since I know there’s so many fans of Sargent among the Muddy Colors audience (and contributors), but you can read all about his backstory here. We all know his famous portrait above, and with modern eyes it’s a gorgeous but pretty tame painting. However at the time (1884 Paris) it was a giant scandal , both because originally the strap was painted off her shoulder and the subject was a somewhat infamous adulteress. Critics also completely lambasted the style, calling it cartoonish and just being nasty like only art critics can be. When Sargent donated the painting to the Met in NYC in 1916, he painted the strap onto the shoulder and insisted they title it “Madame X” to quell the scandal a bit. We think of this painting as a masterwork now but it nearly ended Sargent’s career before it began. He fled Paris for London and never went back.

Luckily for Sargent, there’s no such thing as bad press, and he gained quite a following in England with Lords and Ladies and Dukes and Dutchesses who had huge ancestral castles and estates and needed giant portraits of themselves to stand up to the giant paintings of their ancestors on the castle walls. Sargent’s style was new and daring and different enough to be fresh, but he could still do powerful enough paintings to stand up to Great Great Great Grandpa the Peer of the Realm hanging over the fireplace. Most importantly for rich clients — he made them look great in their portraits – the looser style Sargent developed was very flattering. And when the English heirs started marrying American heiresses for money, Sargent became incredibly popular with the America’s version of aristocracy: The business tycoon families of Astor and Vanderbilt and Carnegie.

And for a while it was great. He was a famous working artist making a name for himself, charging more and more for commissions. And he was passed around high society on both sides of the pond.

Unfortunately, as many of the professional artists reading this know, rich folks can make really entitled clients. Especially as you climb up the social stratosphere. And you can see how he felt about a lot of his sitters plainly in the paintings.

After a while, Sargent made enough money to take summers off completely. Then he started taking long holidays throughout the year. He took fewer and fewer sitters (which I’m sure had the unfortunate effect of raising the caliber and expectations of his clients even higher).

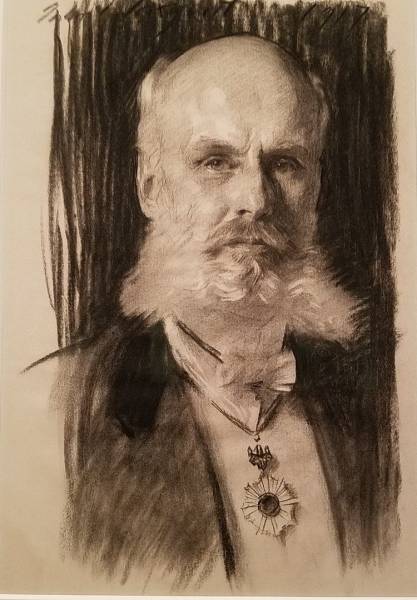

Finally he stopped taking formal portrait commissions altogether. He switched mediums as a way to take the pressure off and also do commissions faster, meaning less time having to share the room with a sitter. There was a gorgeous exhibit of his charcoal portraits at the Morgan Library recently that I was lucky enough to see. This seems to have held off the wolves a while, but finally Sargent got to the point that he didn’t want to paint portraits at all, especially not of the aristocracy.

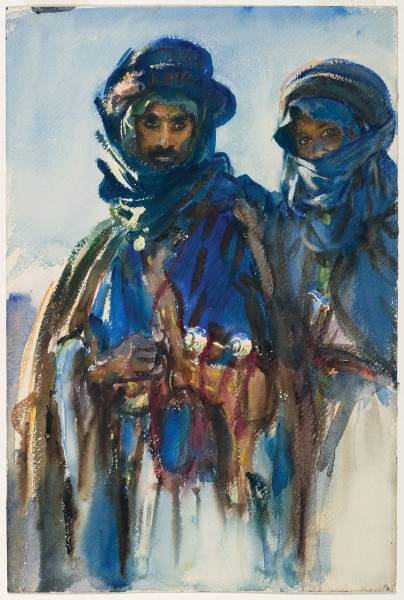

Eventually he traveled for longer and longer and pretty much stopped taking portrait commissions entirely. He started working on mural projects (that he drew out as long as possible or never finished – he spent 29 years on a mural in a Boston Library) as an excuse to do research in far-off lands and ran. He packed his watercolors so he could sketch with paint from life, and found a little of the love of art again. He would enjoy getting outside and painting plein air with his sister, Emily, also an artist. And while he did consent to showing his watercolors in galleries, he was so terrified of ruining this new medium for himself that he refused to sell any watercolors at all, except as whole exhibitions and only directly to museums. He simultaneously worked in oils for landscapes and the murals, but not society portraits. He quickly moved away from the idea of watercolors as sketches for a later oil painting, and considered them full works on their own.

For a while, there were jokes that artists in Sargent’s friend group would get married just to invite Sargent and get a watercolor as a wedding gift. He would only gift them or trade them with other artists.

I think many of us have been there, when the commercial parts of the job stress the art making so much it’s no longer possible to get back to what you loved in the first place. It’s very common for commercial artists to have a different medium they keep just to themselves, whether it’s closely related (like oils to watercolors) or whether it’s further afield, like sculpture or knitting or music. Artists need to make art, but the burden of art as a livelihood can sometimes crush you.

I’ll let this fabulous talk from Erica Hirshler, a Curator of at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston take over and leave you with some of my favorite Sargent watercolors:

Woah, this is fascinating 😮. I’ve always admired his portraits—never realized how much time and effort he spent trying to get away from doing them. It really puts fame into perspective. I’m trying to change my brain from seeing success as a commercial thing and instead see it as enjoying painting/painting the pictures I want to paint…this helps.

Absolutely. There’s a famous happiness study that tracks happiness along wealth. And happiness does increase with wealth to a point of ability to not be anxious about bills, and then plateaus for a while to comfort, but steeply declines again once you head into rich & famous. This is definitely true for most artists I know. Steady work & the ability to pay bills is the initial goal, then the ability to work on what you want to work on, whether thru commissions or personal work, that’s the real goal.

Thank you for your article on Sargent, who has been one of my favorite artists to look at, but I don’t know that much of his history. You clearly made the case that there is regret in making a living, despite that being the initial goal, because it denies you the chance to create the art you love. That was/is certainly my case although it was teaching art that kept me from creating what I love. After about 36 years of that denial, I retired and now I can’t find enough time to create all that I want, but it’s a lovely problem. It was a wonderful read/listen about how Sargent took care of the problem. Thank you. Your article was inspiring.

As a person who makes her living by commercial art, I certainly don’t make the case that you shouldn’t make art your career. I think there’s a balance to be struck. I think if artists expect to encounter these very common problems then we can expect them, and reach out for solutions, and know that many many artists have been down the same road. You have to keep some part of your art just for yourself. Fill the well as much as you draw from it.

Wonderful thank you for sharing

This is some fun information! I grew up with my dad showing me Sargent’s work (all varieties) and I’ve always loved his style, but I never knew the progression from portraits to landscapes and other work. I will confess to staying with my original bank for a lot of years not so much because I had an opinion of them, but because one of the bigger branches in Anchorage had this huge lobby, all lined with original waterscapes and coastal paintings. I’d go in there anytime I had to do banking in person and just stare at the art. One of the few times getting stuck behind a giant line was actually a pleasure.