In recent months I’ve been reading a lot about the reluctance on the part of many employees to return to the office after months (or longer) of working remotely while the COVID pandemic played out. There’s something to be said for doing your job in your jammies and not having to worry about getting the stink-eye from the boss…but at the same time, getting out of the house, going to the office big or small, seeing other people—in other words, separating your work life from your life-life—is, I believe, incredibly important.

Some readers might recall that before becoming an art director for Andrews McMeel Universal for a couple of decades, I worked as an artist for Hallmark Cards for 19 years; I was young and impressionable when I started in the 1970s, still wet behind the ears, and Hallmark, well, Hallmark was HUGE—nearly 5000 people, the majority working at their city-within-a-city headquarters at the Crown Center complex. Greeting cards were big business, as were gift wrap, stationary, home decor, Christmas ornaments, party goods, and all manner of other products. Hallmark was at the top of the mountain; they were an influential and respected part of contemporary culture. Their Hallmark Hall of Fame is the longest-running prime-time series in the history of television (and not to be confused with all of the cheesy Christmas movies running today on their cable channel). There were no desktop computers, no Photoshop, no internet, no email, no texting, no smart phones, no streaming. Everything was drawn or painted or designed by hand. Recruiters fanned out across the country and scoured the art schools for up-and-coming illustrators. The company owned its own printers (when printing overseas wasn’t an option) and operated a nation-wide distribution center. Hallmark and its competitors spied on and sued each other regularly and each tried to lure the other’s executives and talent away. Washington lobbyists were employed to contest each attempt to raise the price of postage (card sales dropped with each increase)…

Though something of a punchline for stand-up comics today for various reasons, there was a time when Hallmark really was the place to be for artists.

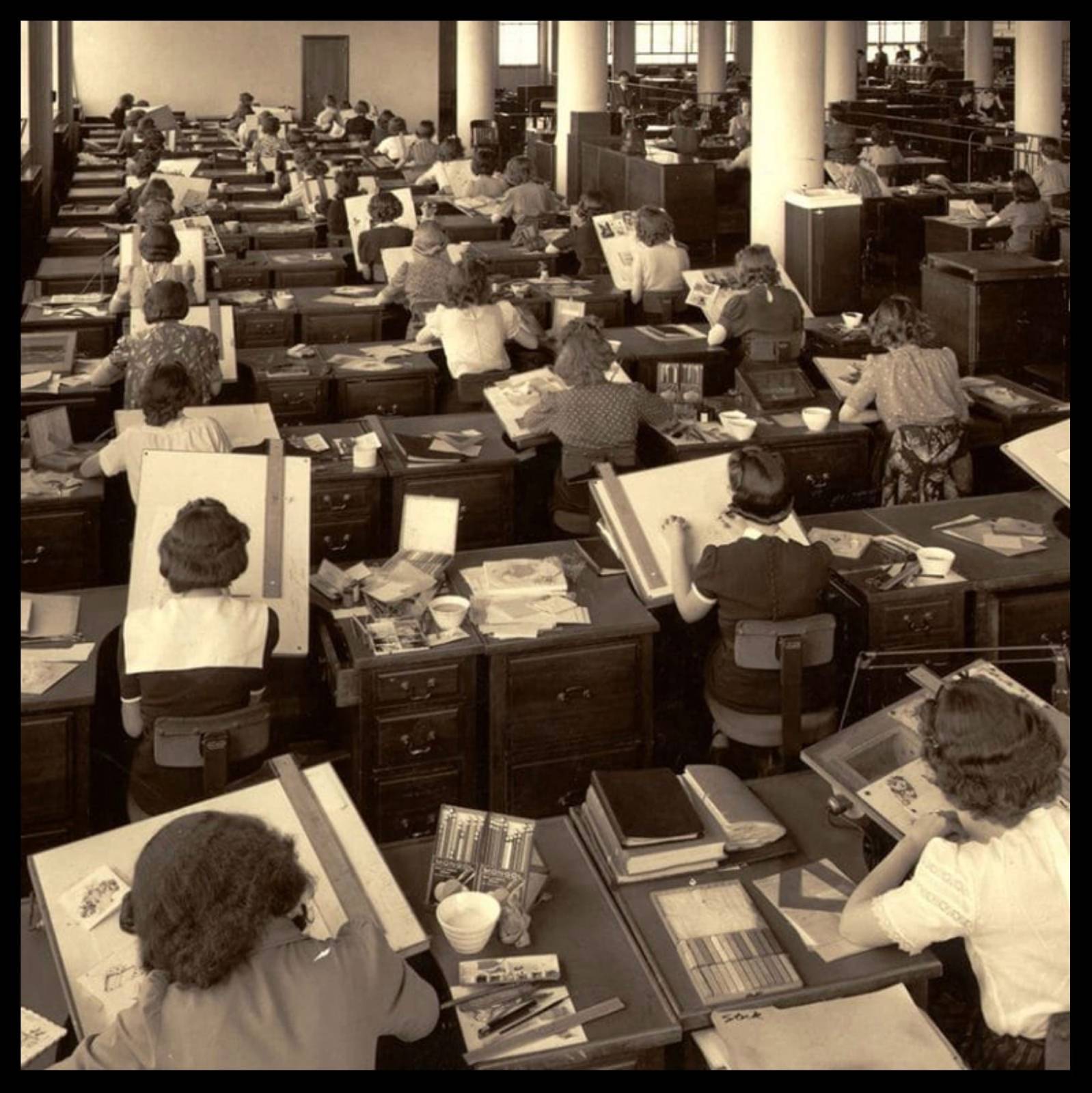

When I was hired the company’s founder and visionary, J.C. Hall, was still alive (he passed away in 1982) and, though retired, very much an on-site presence and influence. George Parker (a really funny and brilliant guy who could scare the crap out of people when he wanted to) was in charge of the Creative Division and, as I understand it, was the one who did away with the dress code for artists (a shirt & tie for men and dresses for women had been required for years), believing it promoted freedom of expression and creativity. Other folks in the company who still had to follow a dress code of one sort or another grumbled about the “hippies” while looking at us with a sense of envy. I might be wrong, but I believe Parker changed the table-to-table set up artists had been accustomed to (see the photo above) throughout the division, giving each what was called an AO2 booth, a personal space of about 5’x7′ with 5′ tall walls and room for a drawing table, flat files, shelves, and storage bins. We were free to decorate it with posters and plants pretty much however we wanted. George liked to say that Hallmark hired artists “for $10,000 a year [about $50,000 in today’s dollars] and all the art supplies they can steal.” And, boy, did we. The best paint, brushes, paper, pens, canvases—you name it, you could get as much as you could ever need or want from the Supply Library (which was overseen by the incredibly bright Glenda Burns). There was also an excellent research library, a gigantic photo studio, workshops to learn everything from sandblasting to screen printing to glass blowing, and an excellent employee cafeteria. Benefits were wonderful and opportunities seemed endless. (George Parker was toppled in 1986 in a coup organized by a handful of his captains that wanted his job: talk about office politics! The conspirators didn’t have George’s brains or leadership skills and everything started to go downhill after his departure. He became a partner at Andrews McMeel for awhile and helped catapult “The Far Side” and “Calvin and Hobbes” to enormous success before retiring to Florida. He died in 2003.)

Above: If you’ve seen the movie Office Space you’ll know what an AO2 booth sorta looks like. And, yes, Hallmark had their Lumberghs, too.

While I was there hundreds of people worked in the Creative Division as illustrators, designers, calligraphers, typography/graphic artists, art directors, writers, editors, engineers, sculptors, and more; I met and worked with men and women of all races, religions, ethnicities, political leanings, and sexual orientations. I worked with conservatives and liberals, the industrious and the lazy, the humble and the arrogant, the puritanical and the promiscuous, the amazingly smart and the surprisingly dim, the incredibly kind and the decidedly creepy—and more than a few who were 100% bugfuck. Admittedly, there was terrible nepotism and cronyism and the chosen few got rapid promotions, research trips to Europe, and generous raises whether they were deserving or not while the rest of us (who weren’t “superstars” or toadies) literally did most the work and made the company most the money without much hoopla. That’s life in a big corporation.

People would often get away with saying or doing some incredibly awful things, things that would certainly get them fired in a New York minute everywhere today (and possibly back then, too, if anyone had enough courage to go to Human Resources): there were shocking examples of misogyny and misandry (no gender has a monopoly on hateful behavior). I never had any problem calling anyone out, regardless of who they were or what their title was, when they were being insulting or rude or trying to pull stupid crap: it didn’t particularly help my career, in retrospect.

Canabis, recreational or medicinal, was illegal everywhere—which didn’t stop people from smoking a joint on the way to the office and another in the parking garage at lunch. Whether the preference was pot or pills or something else, there was always a small group of associates who were stoned every day. Just as there were those who either came in drunk or got plastered at lunch and stayed that way: I don’t know how they managed to function (and it caught up to most eventually). Writers and editors would routinely disappear afternoons for “off-campus brainstorming,” usually at Kelly’s, a favorite watering hole.

There were sexcapades (don’t worry, you lusty folks: I won’t tell what I know), affairs, crushes, stalkers, heartaches, and romances (I knew more than one couple who met at Hallmark and eventually married, including Cathy and me). And, as with any corporate population of this size, it was inevitable that we lost friends and coworkers to disease, accidents, suicide, and murder (Cathy worked with a woman who was found dead in a basement with her boyfriend, a drug deal gone horribly wrong).

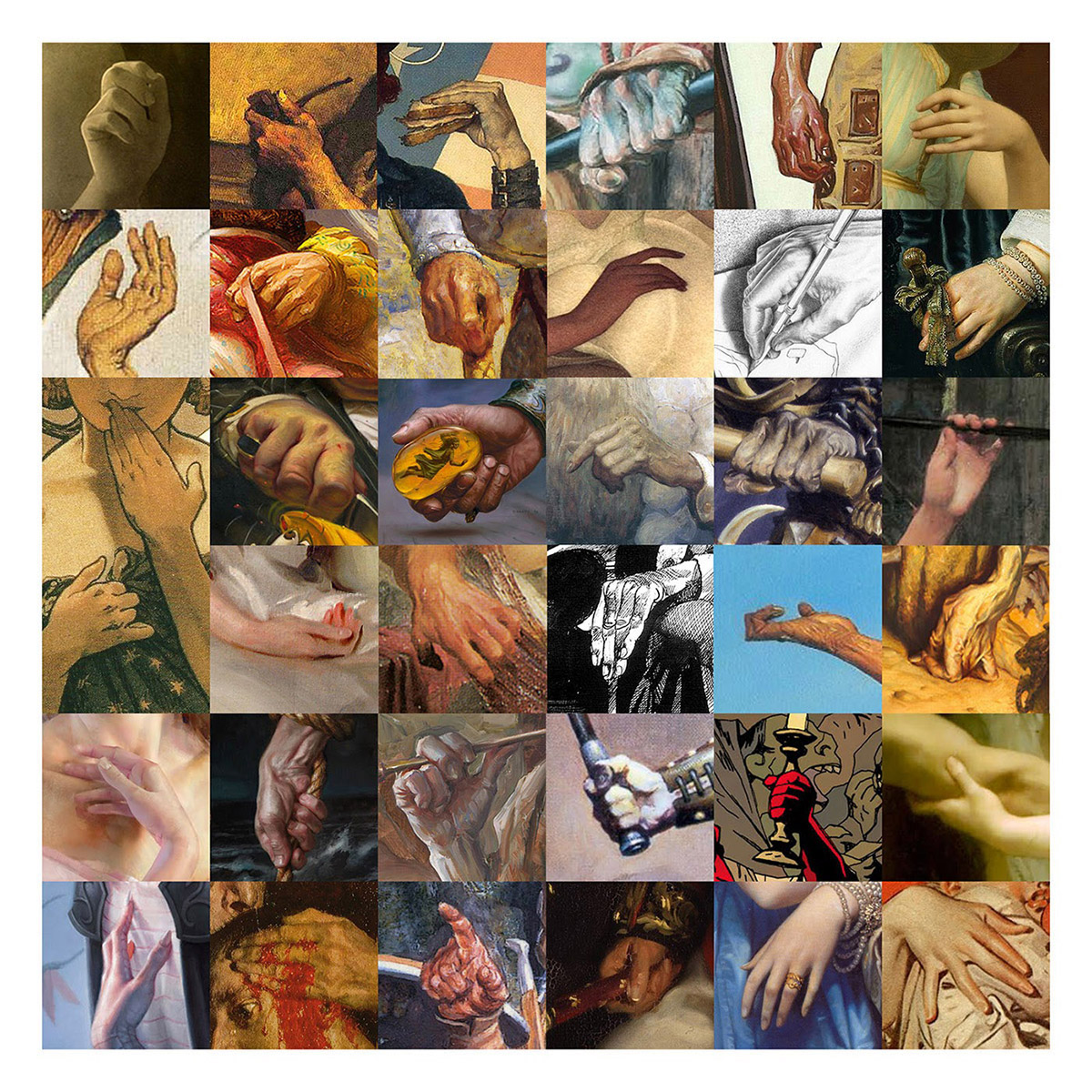

On a happier note, I got to meet and talk to some amazing visiting lecturers like Marshall Arisman, Robert Benton, Art Kane, Gahan Wilson, and Betty White (yep, that Betty White). I was inspired by and fortunate enough to becomes friends with absolutely astonishing Hallmark creatives like Mark English, Tim Kirk, Thomas Blackshear, Lainey Koepke, Vern Dufford, Dawn Rivera, Hanh Crow, Susan Sifers, Pat Barnett, Pete Noth, Larry Gusman, Ezra Tucker, Bob Haas, Rick Cusick, and many, many more.

Above: A caricature of me by Thomas Blackshear from way back in the days when I had hair and a twinkle in my eyes.

I’m not terribly nostalgic and don’t look at the past through rose-colored glasses: as with any job, I had good days and really crummy days, some bosses who were great and others that were utterly rotten. I didn’t like everyone and everyone didn’t like me—which was perfectly fine. Part of being an adult is learning how to get along with the people you work with, whether they’re your buddy or not, so in many ways I grew up at Hallmark. Sure, when asked I can bitch and complain about past BS with the best of them—and with good reasons. But I also have to admit…I had a helluva lot of fun, too. For a time there was something very special going on at Hallmark, much more than it simply being a place to work—and much of it certainly had to do with the mix of artists working together under one roof. It was someplace rare, sort of like lightning in a bottle, and sometimes my associates could be damn funny. I thought I’d share a few humorous studio experiences today.

Wabbit Season

These first stories aren’t mine and happened well before my days in the house of cards…but I thought I’d start with them nonetheless simply because of the people involved. They’re, for the most part, really pretty innocent, but shows there was always something of a “Them (meaning management) Against Us” dynamic going on there.

Harry A. West was an artist at Hallmark in the 1960s and he snapped this photo of young scamps Brad Holland and Wendell Minor showing off their handiwork years before they left Hallmark and became legends of the illustration world. Harry explained, “Brad had done an over-nighter (no over-time), and rather than go home at such an early hour, he created this giant rabbit to welcome the in-coming new artists. I took this snapshot early in the morning before ‘management’ ordered disassembly. It was taken in an area adjacent to the 8th Floor Design Department in 1966. That is the ‘entrance’ to the newly formed Humorous Illustrative Section.” Fellow artist Jan Manco remembered, “[Brad Holland] was often asked to remove his take on decoration deemed inappropriate by the conservative powers that be…Brad was notorious for challenging life in general. Corporate life was no exception.”

There are tales about shirtless chair races down the halls with tremendous crashes, races up the stairwells from the first floor to the ninth, and other after hours shenanigans. Rumor had it that the Contemporary Cards illustrators at the time were so rambunctous and rowdy that Mr. Hall had them exiled from the headquarters to a separate building so that they wouldn’t scare everyone else. One legend tells of an artist who snapped one day, announced it was time to give the boss a beat down, and went running toward the executive offices: he was literally tackled by security before he could get there. Naturally, he was fired—but that wasn’t the end of the story. For weeks after getting sacked he would sneak in with the morning crowd, slip into an elevator with other employees, then, just before the doors closed, poke his head out and yell and wave at the security guards to let them know he’d gotten past them. A sort of Benny Hill scene would ensue (see the video at the end of this post) as the guards chased him from one floor to the next until they finally caught him and tossed him out. I think he went on to become a very successful cartoonist for The New Yorker.

Illustrator Stu Neyland recalls an artist who would torment his neighbors with what he called “nerkles”: “Little balls of kneaded eraser that he would launch great distances into random booths. It finally ended when he started launching nerkles ‘on fire.’ I think he dipped them in Bestine before he lit them. He used a rubber band slingshot.”

Fortunately in any of these activites and incidents nobody died, no bones were broken, no eyes were put out, and nothing burned down.

Why We Can’t Have Nice Things

Hallmark decided to construct a “showcase artist studio” on the 9th floor for the Styling & Innovation Department. Nicknamed “The Jungle Room” because it featured open-concept studio spaces without walls consisting only of shelves and a drawing table surrounded by all sorts of enormous potted plants and trees. Phones were muted to encourage a quiet, creative environment. Small lizards were added supposedly to eat bugs, but they mostly just pooped on the tables and artwork. It was all very silly if you ask me. Anyway, one of the decorative features was a large fountain (which ultimately wound up leaking through the floor to the departments on 8 and had to be removed). We were amused to arrive one morning to discover that a toilet had been installed in it: Alex Kreicbergs eventually admitted that he, Terry Lee, and Myron McVay were responsible. “Myron did the stand, I made the floor, and Terry hauled in the toilet. It fit perfectly over the pipe and actually ‘flushed’ when the fountain was turned off. Quick assembly and, alas, ever quicker disassembly.” The trio’s timing for their stunt couldn’t have been worse: the day they installed it was the same day a senior vice president was giving a tour of the new space to a group of visiting V.I.P.s. You can imagine their reaction.

Lingerie. Remember lingerie?

We were always moving around for one reason or another and for a while my booth was next to a great friend of mine, Susie H. She was smart as a whip, pretty as a picture (and she modeled for me for several freelance gigs), mischievous as hell, and, when she chose, meaner than a junkyard dog. I drove her to the impound lot one day to identify her car after it had been stolen (it had been stripped and torched so it turned out there was nothing really to identify), chaperoned she and another woman once while they bar-hopped in Westport (a hair-raising and memorable night: we’re lucky we survived), and moved her out of her apartment and into her fiancé’s house when he was indisposed. In other words: we were close.

One day I was drawing at my table when suddenly I was hit in the face with a black bra; Susie had taken it off and tossed it at me over the wall. Without a moment’s hesitation or saying a word I put it on my head, hooked it under my chin, and went back to drawing. My silence finally got the better of her curiosity and she peeked over the wall to see me cheerfully sketching away while wearing her bra as a hat. Susie immediately demanded it back: I refused, and we bantered back and forth for awhile. “Gimme!” “No.” “Gimme!” “No.” When I stood up to continue our witty repartee she suddenly let out a high-pitched, ear-shattering scream straight out of a horror film then yelled, “Arnie Fenner! Take off my BRRAAA!!!” As she stood smiling at me, heads popped up in the surrounding booths as if we were in the middle of a prairie dog town. Blushing bright red, I slowly unhooked it and removed it from my noggin…then I grabbed her shoulders, turned her around to face our grinning audience and, holding the bra behind her head and positioning the cups like giant mouse ears, asked everyone watching, “Who’s the leader of the club that’s made for you and me?” and, as Susie now blushed as red as me, they sang in unison almost as if on cue, “M-i-c-k-e-y M-o-u-s-e!”

Susie pranked me (and others) a fair bit over the years (some were mild and others incredibly Holy-Mother-of-God-why-did-you-DO-that?!? embarrassing) and one of the most popular was…

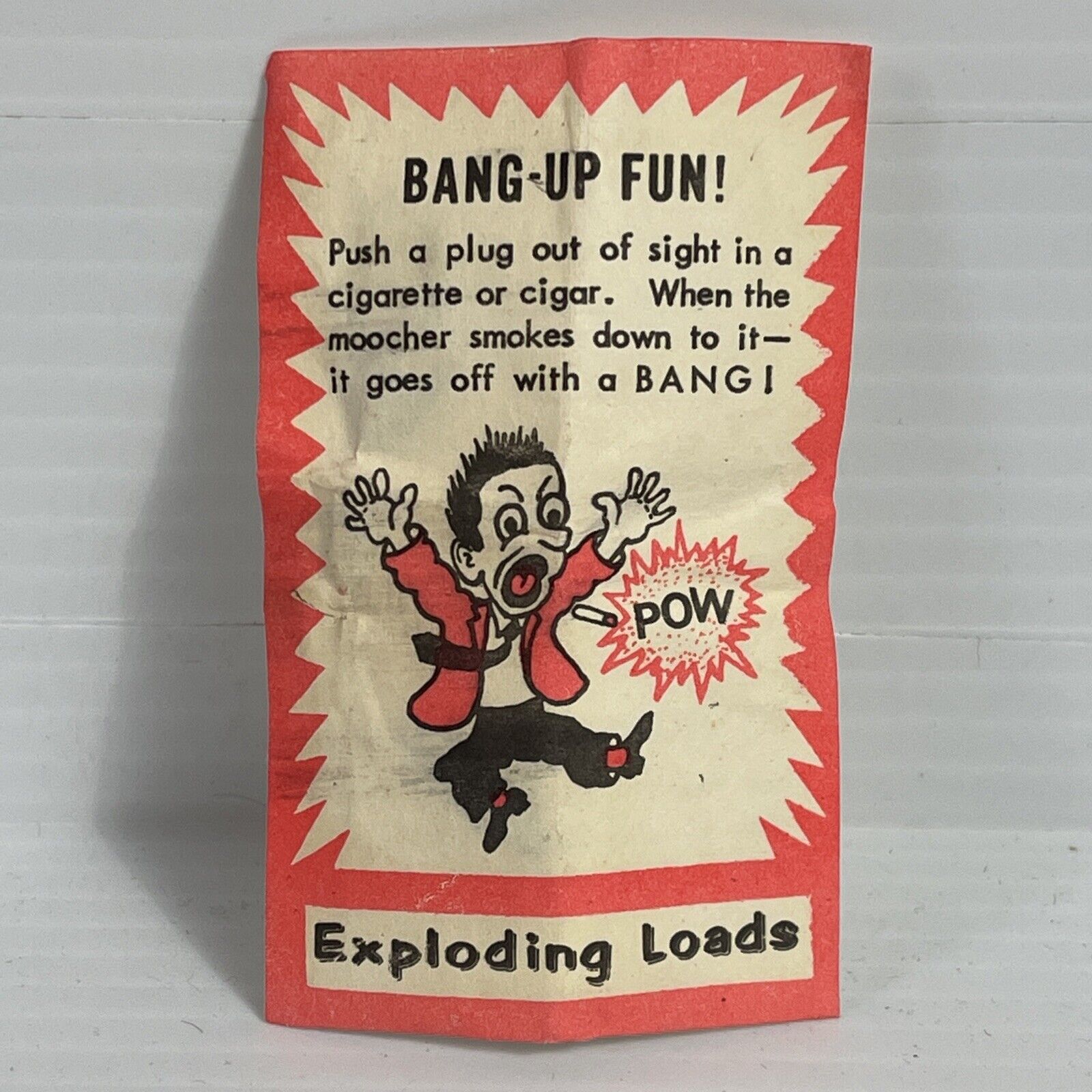

Bang-Up Fun!

There was a time when it seemed everybody smoked and you could smoke anywhere—and we did, me included. Smoke in your booth, smoke at meetings, smoke in the cafeteria, smoke in the restrooms, smoke walking around, smoke in elevators: it was no big deal. One art director was a chain-smoker and walking into her committee room to review your art was like stepping into a smelly London fog. Of course, it was as bad for you then as it is now, but it was accepted and the break rooms had cigarette vending machines and there were crown-shaped ashtrays everywhere.

So I was a smoker way back when. One day I noticed that after lighting up there would be a fizzle, almost a tiny spark; I figured the tobacco was unusually dry and didn’t think much of it. Little did I know that “someone” I sat near had bought a packet of joke explosive charges and had been secretly slipping them into my cigarettes, one at a time. Disappointed that the desired explosion hadn’t taken place, Susie and her co-conspirators Paula C. and Cindy G. took all the remaining charges and packed them into one cigarette…and waited. Cathy was present but says (snorting) that she was not a participant, only an observer. Yeah. I bet.

Anyway, time passed and I had to run a piece of art back to the dark room; without having a clue about what was going on I took the boobytrap out of the pack, lit up, and headed on my merry way. Our boss (Barrie Maguire, a Clio Award-winning ad man and easily one of the best bosses, bar none, I ever worked for) was walking out of his office as I was strolling by when suddenly the cigarette IED exploded with a huge bang. I imagine I was standing there with black soot on my face, shreds of paper dangling from my lips, and my hair on fire. Barrie took one look at me, ducked his head to hide his laughter, turned around, walked back into his office, and shut the door.

Naturally, I immediately returned to my area only to find it completely deserted: you could’ve heard crickets and the hooting of a distant owl. Tumbleweeds were rolling down the aisle as if it were a ghost town.

They had all ducked lower than the AO2 walls so I couldn’t see them from the other side of the department and run for the hills (i.e. the ladies room). I asked Cathy last night why, if she hadn’t been involved, did she run, too. She replied happily, “Well, everybody else was running so it seemed like the right thing to do.” A likely story.

Writer and activist Max Eastman once said, “It is the ability to take a joke, not make one, that proves you have a sense of humor.” While some might be shocked or offended by these tales…they were jokes and I definitely had a sense of humor. I’ve got plenty of other stories, some that happened to me, some that I observed or heard about—and I’m sure that anyone who ever worked in a corporate art department or large studio or any place else where a lot of artists are together have their own to tell—and maybe one day I’ll get around to sharing them. “Dick Hertz” and “Me So Horny” still make me laugh.

Today, Hallmark is only a shadow of what it was when Cathy and me worked there; there have been layoffs for years (the most recent last month) and the Creative Division has been whittled down to almost nothing. Its staff of artists and graphic designers has progressively been replaced by contract workers who are far less expensive and, I would guess, much less troublesome.

But the point I really wanted to make is this: everything I experienced in the office, everyone I came in contact with, for good or ill, helped me grow as an artist and as a person. Socializing with a wide variety of people on a daily basis, getting out of my comfort zone, joking or fighting or commiserating with people, all helped expand my purview, empathy, compassion, and tolerance. As an artist I learned more about composition, color, content, and technique from my coworkers than I ever did in school. I learned how to follow directions, take criticism, and constructively give it. I learned how to be a good art director from Deidre DeVey and how to not be a bad art director by observing all the others who weren’t anywhere near as good as she was. Opportunities followed as a result, opportunities that would not have happened if I were only working from home. Humans are communal and good things happen from simply being together; too often bad things happen when the face-to-face connection is removed and we only communicate via technology. Years later…what kind of memories do I have from exchanging emails or texts or going to endless Zoom meetings before I retired during the pandemic (other than that Zoom meetings are awful)?

I mean, really: I’d much rather be in an office where someone might throw their underwear at me.

Love it Arnie. Stirred up some old memories for me.

Thanks, Bill—and I’m sure you’ve got plenty of stories you could tell. And I imagine Greg Manchess got into some mischief when he was a sprout at Hellman.

Hey Arnie, entertaining, truthful and touching. I remember you and those times so well. And gosh, thanks for the surprising shoutout…I tried my best, glad I left some good feelings behind. Your erstwhile co-Hallmarker, Deirdre (DeVey) Britt.

Ah, thanks, Deirdre. And I was serious: I learned so much about thoughtful art direction from watching you in committee. You had an astonishing ability to quickly evaluate art, identify what worked, and clearly explain how to fix any problems without hurting anyone’s feelings. I tried my best to follow your example when I was doing the job at Andrews McMeel. Hope you’re doing well!

Ah, thanks. Truly. So nice to hear. Trust you enjoyed Gary’s old stomping ground at Andrews McMeel. They threw great parties!

I enjoyed this so much and I thank you. That was an amazing well thought out, well written article on the Hallmark we once knew. You nailed it on the head! Interacting with likes of creative at Hallmark Cards could not have been better in ‘our day’. They are years I treasure and no doubt do not exist today. When I read of former employees moaning about the Crown Room closing I think it might as well join the past like everything else we were blessed with. It’s simply a different world.

Sad, but true.

Thanks, Alice. Yeah, I’m sure I wouldn’t recognize the place anymore and only know a handful of people still there. All things must pass, I guess. The people I liked when I worked there, I still like; as for the people I didn’t like then, well… 🙂

On another note, I thoroughly enjoy all the rare vintage photos you post on FB: all kinds of surprising and inspiring stuff! Stay well!

Thanks for the shout-out. I can only add that there was so much more that extended beyond “Creative” and exemplified what happens when truly talented, bored, and under utilized folks worked together. I would point you to Amazon for a copy of the self-published; The Art Factory: “Mad Men” meets the Greeting Card Industry

by Barrie Maguire | Apr 3, 2013.. Be well and thanks for the memories…

Thanks, Alex. It’s a classic story. And what I neglected to mention was that after Boss Barrie Maguire had gotten the ill-fated call from the powers-that-be to have the toilet removed PDQ—which he did—that very same toilet turned up in his office the next morning. Now I wonder who oh who could have been responsible? 🙂