“Until the artist arrives at the point where he realizes that by drawing a single panel he has a single work of art that exists by itself, only then can all the panels live together. And then you reach a totality that is completely out of the realm of the infantile kind of page continuities that comics are filled with.” —Bernard Krigstein in an interview with John Benson. Squa Tront #6, 1975.

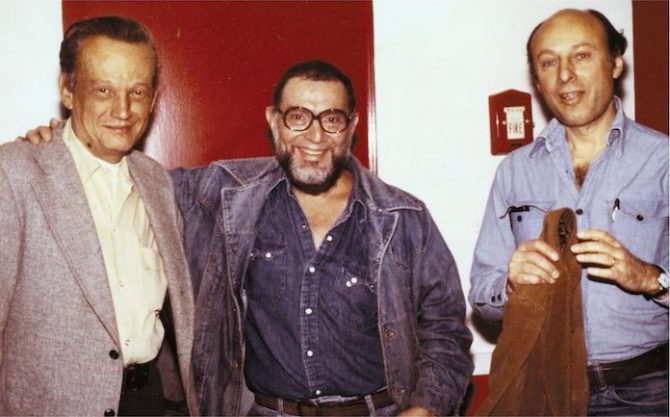

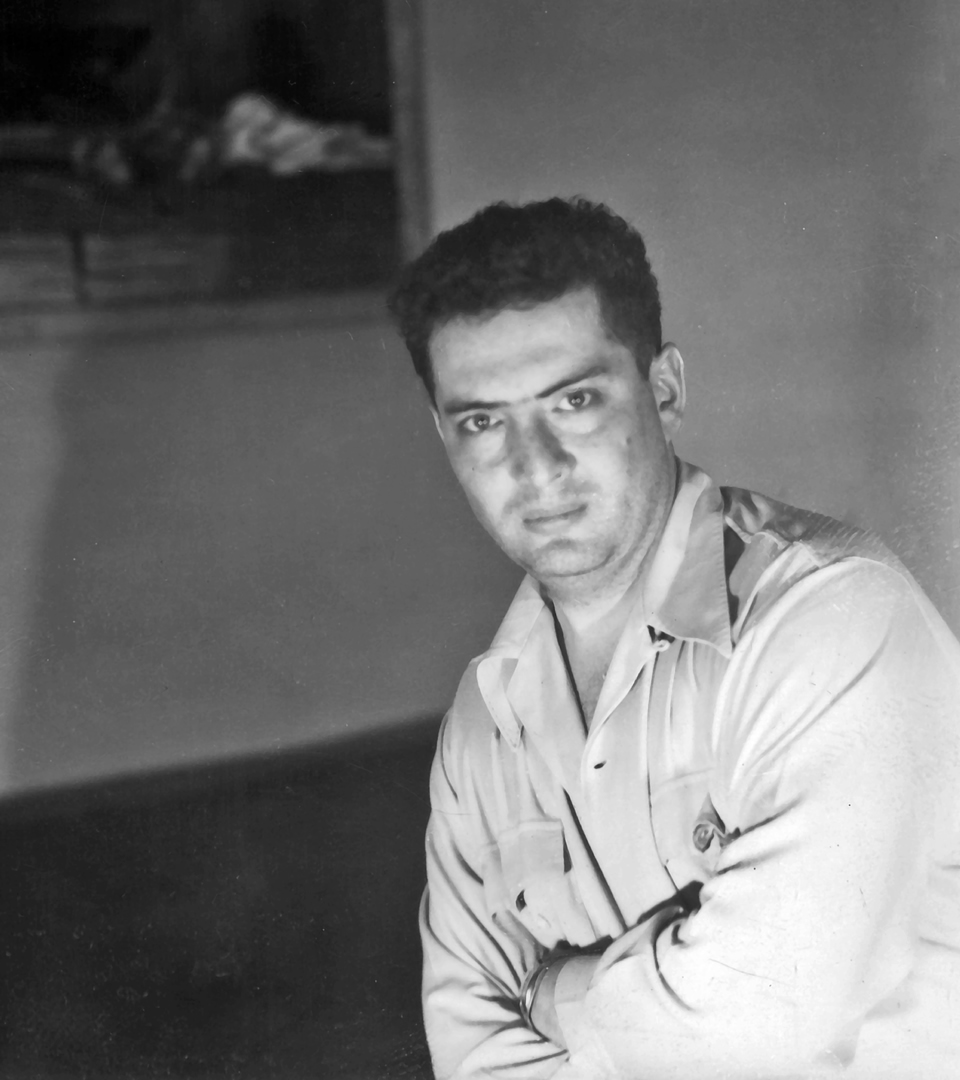

Bernard Krigstein [1919-1990]—shown above and in the center of the photo leading into this post flanked by fellow creators Wallace Wood and Harvey Kurtzman—was an illustrator, gallery painter, and art teacher but is perhaps best known for his comics stories published in the 1950s. Born in NYC he studied art at Brooklyn College and started his career drawing for Harvey Comics and Prize Comics before joining the Army in 1943. Following his service in WWII, he restarted his career in 1945 and worked for Fawcett, Hillman, National (DC), and Atlas (Marvel).

In 1952, Krigstein organized an effort by himself and fellow comics artists Arthur Peddy, George Evans, and Edd Ashe to found the comics industry’s first attempt at a labor union, The Society of Comic Book Illustrators; it lasted less than a year and only succeeded in getting Krigstein blacklisted by his clients. But Harvey Kurtzman encouraged EC Comics’ publisher William Gaines to give him work and it was for EC that Krigstein went on to create some of his most unforgettable work, including his adaptation of editor Al Feldstein’s story “Master Race.”

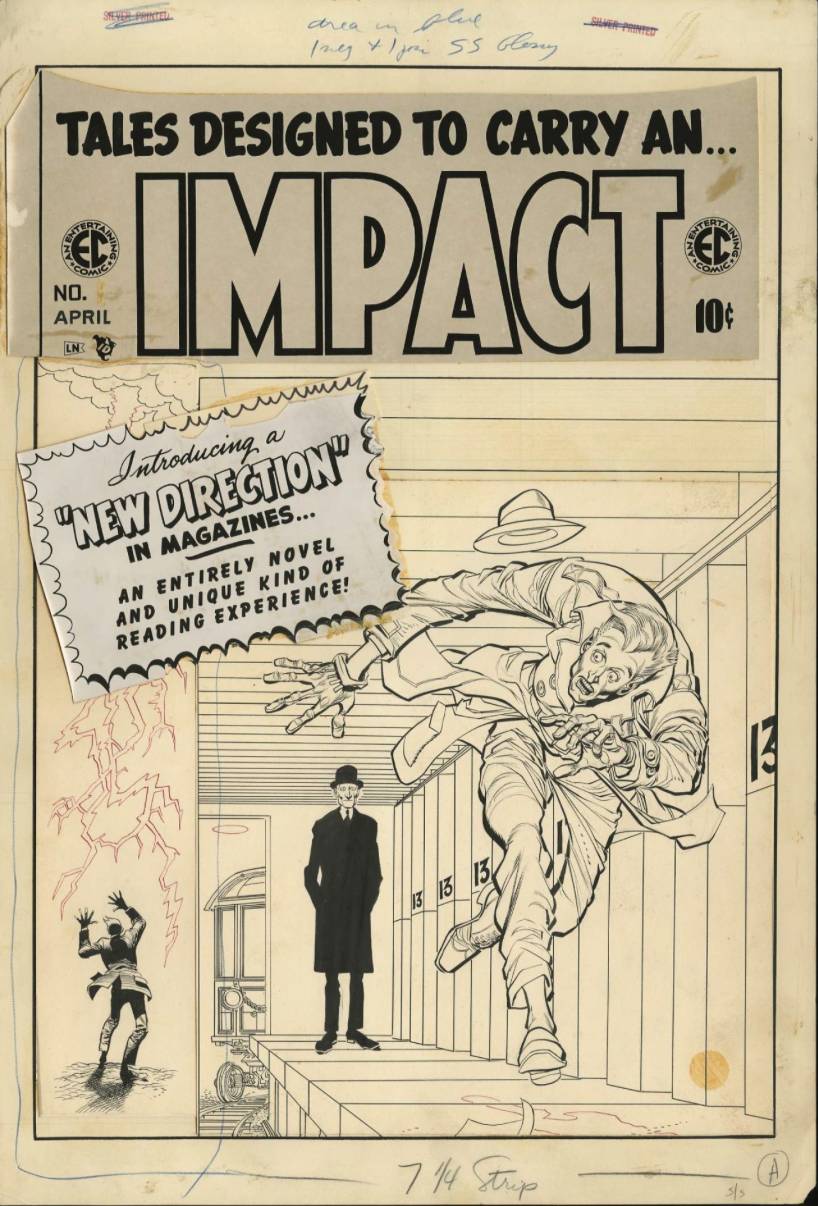

Above: Jack Davis drew the cover for Impact #1 interpreting a scene based on “Master Race.”

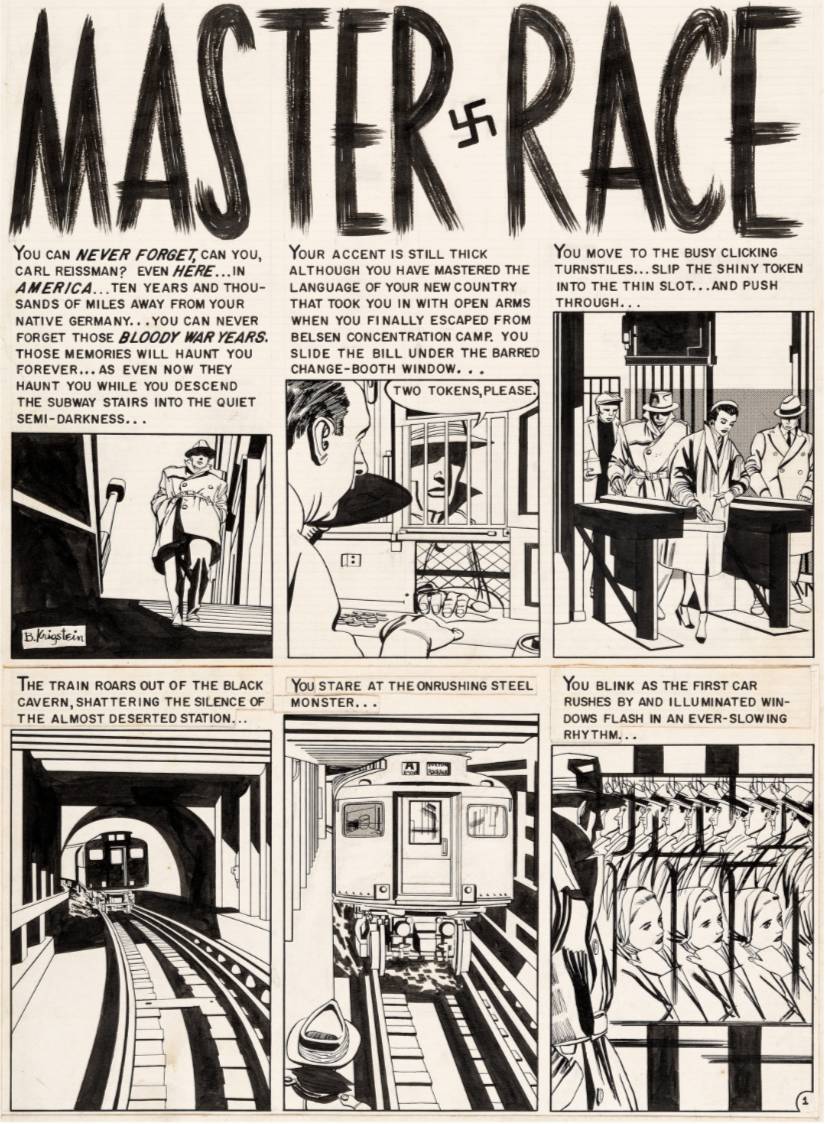

By the mid-1950s EC had been one of the prime targets of the Congressional hearing on juvenile delinquency because of their horror comics like Tales From the Crypt and The Vault of Horror and they were in the process of trying new titles to stay in business. One of those new titles was Impact, a comic dedicated to stories with shock endings that was sort of a toned down, Comics Code-friendly version of EC’s earlier Shock SuspensStories. Krigstein was assigned “Master Race” to illustrate for the first issue [April, 1955] and he immediately recognized the possibilities of doing something beyond what was normally expected. The horror of The Holocaust was an extremely sensitive subject in the 1950s and for it to be honestly described and depicted in a comics story—much less any other media—was largely unheard of. Krigstein had routinely argued with Feldstein and Gaines about the limits—and wordage—of the stories EC usually assigned him; sometimes he won, most times he lost, but after receiving the script for “Master Race” he was inflexible in his demand to expand what had been planned for six pages into an eight page story. After much skepticism and debate, Feldstein and Gaines relented and granted him permission to adapt it the way he thought it should be. The results (colored for printing by Marie Severin) were so striking and powerful that Gaines readily reworked the issue’s contents to accommodate the two extra pages.

The protagonist of the story is a Nazi death camp commandant named Carl Reissman who has managed to escape justice after the war and is living quietly in the United States in anonymity until he is spotted riding the NYC subway by one of his victims. The situation may have influenced William Goldman for his 1974 novel (and John Schlesinger’s 1976 film adaptation) The Marathon Man, in which Dr. Christian Szell, a Nazi war criminal (played by Laurence Olivier in the film), is recognized and pursued on the streets of Manhattan by several Holocaust survivors.

In his expansion of Feldstein’s script, Krigstein had stretched out certain sequences in purely visual terms, the likes of which had never been tried before in comics: repetitive strobe-like drawings mimic the motion of a passing train; Commandant Reissman’s final moment of life is broken down into four individual poses of his desperate fight for survival. As Art Spiegelman, the Pulitzer Prize-winning creator of the Holocaust-themed graphic novel Maus, described the effect in The New Yorker, “[Krigstein] disdained shortcuts and easy solutions, and replaced the cartoonist’s vocabulary of sweat marks and action lines with a painter’s language of composition and form. It’s as if the other cartoonists were expressively drawing Yiddish while Krigstein eloquently drew Hebrew … The two tiers of wordless staccato panels that climax the story have often been described as ‘cinematic,’ a phrase thoroughly inadequate to the achievement: Krigstein condenses and distends time itself… Reissman’s life floats in space like the suspended matter in a lava lamp. The cumulative effect carries an impact—simultaneously visceral and intellectual—that is unique to comics.” Spiegelman credits “Master Race” as a seminal influence on his work; critics and historians have described the story as the Citizen Kane of the comics medium.

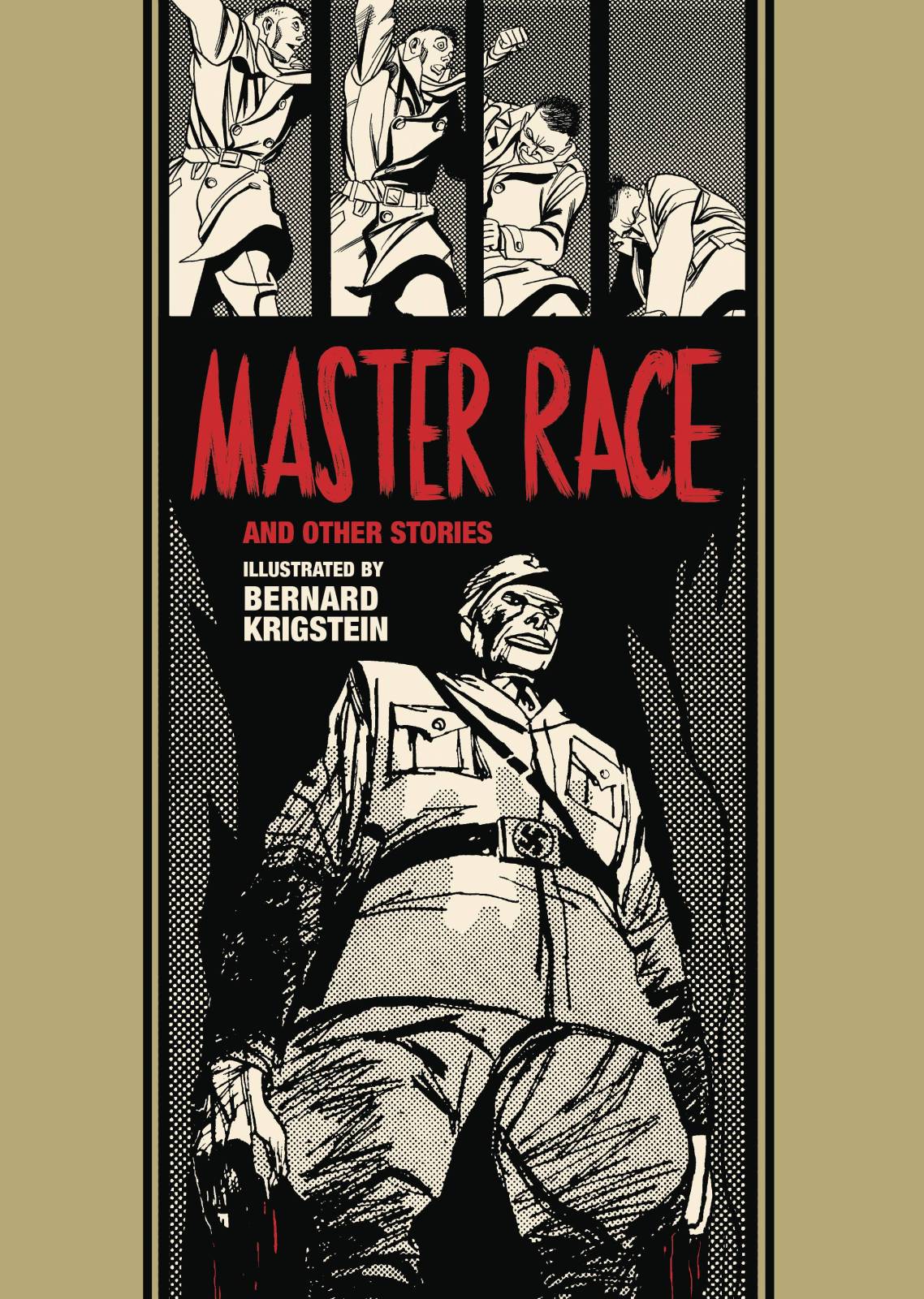

Unfortunately, Impact didn’t last the year and all of EC’s comics—and other experiments—were eventually cancelled with the exception of Mad, which was turned into a magazine. But the importance and influence of Bernard Krigstein’s interpretation of Feldstein’s “Master Race” script are immeasurable and have continued to be powerfully felt nearly 70 years after its first publication. Fantagraphics produced Master Race and Other Stories (seen above) in 2018 collecting his best EC stories (which also included “The Flying Machine” based on a short story by Ray Bradbury and “Slave Ship”), followed by B. Krigstein Vol. 1, 1919-1955, a retrospective edited by Greg Sadowski, in 2002. The original art for “Master Race” was sold by Heritage Auctions for $600,000 in 2018 (hopefully to a museum).

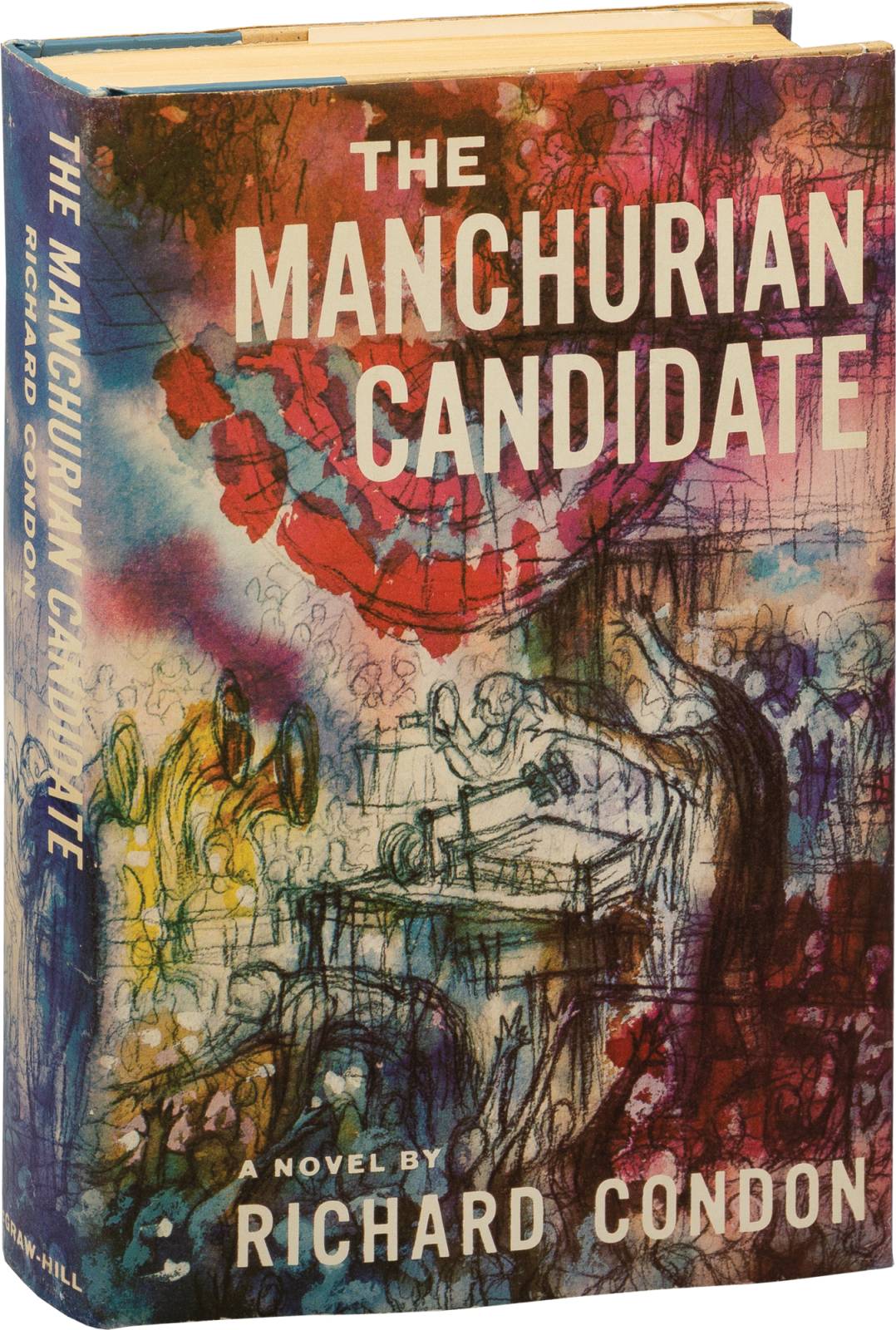

For his part, Krigstein left EC after another argument in 1955 and comics entirely in 1962; save for an occasional interview he rarely looked back, becoming a successful illustrator (see his cover for The Manchurian Candidate below), Fine Artist, and instructor at New York’s High School of Art and Design.

You can learn more about Krigstein and “Master Race” and much more in the videos below. Enjoy.

Really enjoyed this Arnie, thanks!

Thanks, Bill. I’ve always been fascinated by Krigstein. He was never the most popular of EC’s artists among the fans but certainly did some of the most interesting work.