If you’ve been practicing drawing for years, a newbie or a seasoned pro you know that age-old advice, “draw from life.” It seems to be the answer for all sorts of art questions, like, how can I get better? How can I draw faster? How do I find my style?

First, what is drawing from life?

Drawing from life, or sometimes called, “drawing from observation’ is a practice where the artist draws what they see in front of them, as they see it, as true to life as possible. It’s a formal and informal practice. Many artists use a sketchbook to record these types of studies. It’s used in every art school I’ve ever heard of.

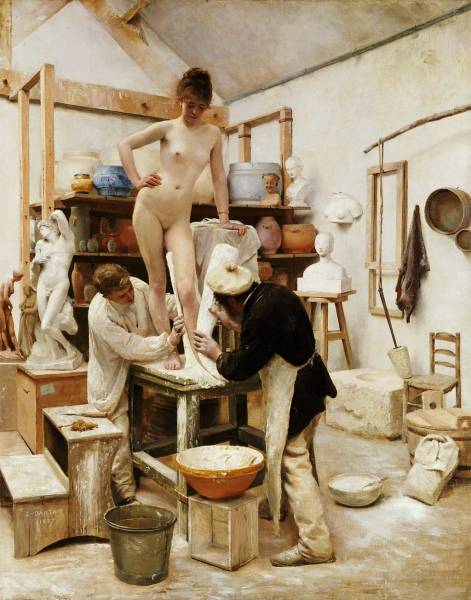

It’s one of the oldest, tried, and true ways of learning how to draw. Egyptians were the first to create casts of their deceased and drew from the sculptures for portraits but the practice took off in during the renaissance. Artist have always known observing subjects and recording how they interact with light, in time, builds your understanding of the world. I’ve heard the advice “draw from life” over and over, but my approach to life drawing was missing something.

Break a rule.

Picture me in art school, pinning up my work for a big end-of-project critique. I was a bit of a goody-two-shoes and gave the piece my all, likely spending double the amount of time on the project than any of my peers. Nothing frustrated me more than seeing my classmate’s work, who broke the rules of the assignment and came away with a show-stopping piece. URGH!

Drawing from life doesn’t mean we abandon everything we know. Sometimes life does weird things visually that don’t translate to paper. You may be familiar with the phrase “don’t be a slave to your reference.” The time to practice using your creative license in your studies from life, not the big painting on your easel. Drawing from life teaches us how to experiment with our creative license but we rarely are taught to approach it that way.

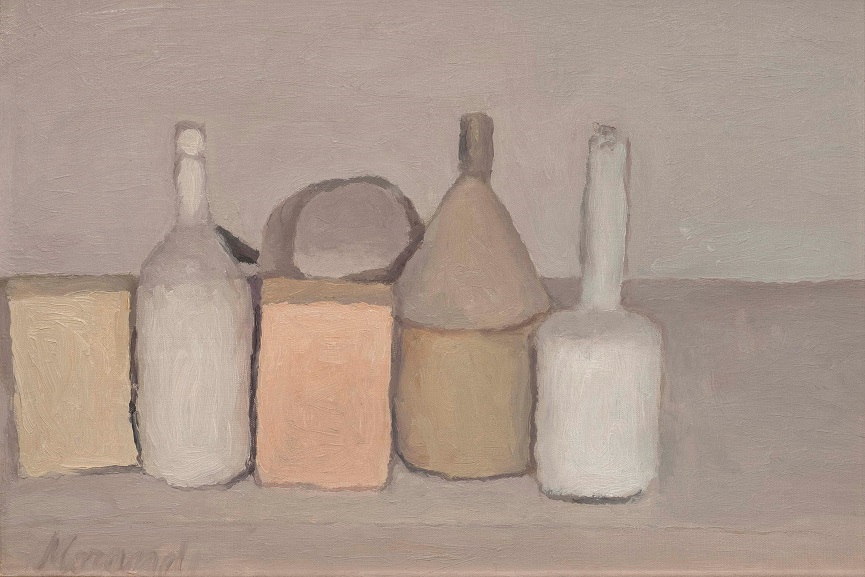

If a pose doesn’t inspire you, fix it. If a tangent is dominating your Plein-air painting, cut it. Omit what doesn’t work for you. Tweak what needs tweaking. There could be a secondary (third, or fourth!) light source in the room that’s flattening your subject, or making confusing shadow shapes – omit it. If moving that pear closer to the apple a smidge would improve the composition… go for it. It took me a long time to break from this conflicting advice. Your taste, and your eye is what makes you, you and the details you edit or omit are the very beginning of your style.

Bring Everything to the Table

“Draw what you see, not what you know” is a common phrase to hear while drawing from life. I have huge issues with this saying and as a teacher, I used to say this!! When this advice is taken too seriously (see “break a rule” above) mental torture and bad drawings ensues. (Guilty.)

Drawing is hypnotizing. I can zen out and draw from observation, fairly successfully, without thinking, well… anything. No doubt, there is a place for this mediation in my life but if we want to see our drawings improve, I have to stay engaged. When I’m drawing from life (or reference) and I’m zoned out, it’s more an act of copying what I’m seeing than constructing, engaging and transforming the subject.

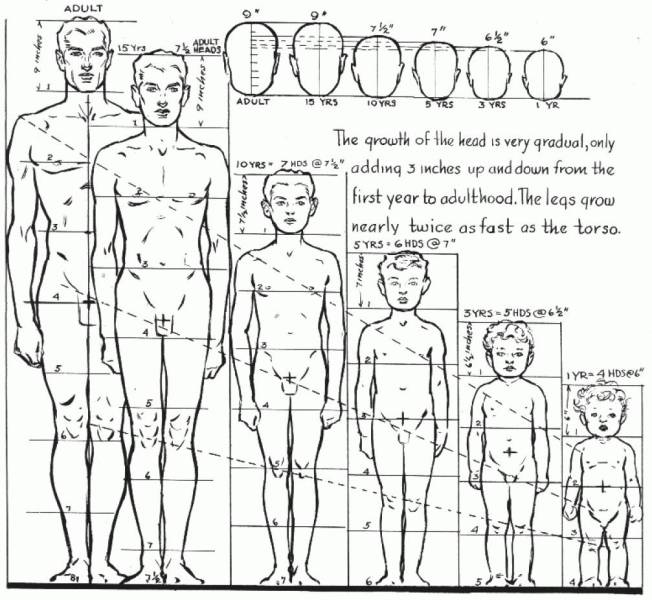

Some artists say that doing fast-timed sketches (10-30 seconds) will help you stay engaged and learn how to “get down what’s important.” But if you don’t have any foundation for your subject, if you don’t know what’s important – you’ll be left in the dust by the timer over and over again.

So if we want to make good studies that teach us about the world, we have to come from an informed place. If I know about the foundation of the thing I’m drawing and marry that with the information that’s right in front of me, I can learn even more about the subject. It’s one of the reasons why artists of the most prestigious academy’s historically studied the casts before they were allowed advanced to working with a live model.

How can we get informed? Isn’t that what “drawing from life” is all about? Before I went out to draw with these 2000-pound animals, for my work on “A HORSE NAMED SKY” I did studies of their musculature. I learned the basic shapes of the larger masses. When I was in the field, things clicked, oh “That’s that one muscle I saw before,” “That’s the knee joint there.” “Wow, look at how far it can stretch!”

Those “clicking” or “ah-ha” moments are crucial. It’s not memorizing muscle facts, it’s kinesthetic learning. I wouldn’t have come away with much had I not been at least, a little prepared. If I can put at least a bumbly drawing together from my imagination of the subject, things are going to go a lot easier in the field. Drawing subjects that are moving, makes it even more important that we have a base in our heads to work from. I wish I knew this all sooner.

Lazy Approach

I got this idea from a mentor of mine who keeps a master painting as her lock screen/background. She thinks, in seeing it often, she’ll slowly take in the colors, form, lighting, and technique. I think she’s right so I tested something out. I printed out Proko’s anatomy of the neck drawing (something I was struggling with) and posted it in the shower. Actually, I posted it all over the house at first but I got tired of explaining to visitors what was up with all the jugular drawings, so I just had it in the shower. I didn’t make big efforts to “study” it, it was there and I looked at it. Might have traced it on the foggy glass a few times. That’s it.

After several months, I noticed that when I went to draw a neck on a character for an assignment, Proko’s anatomy drawing was starting to appear in my head. The image became clearer and clearer as time went on. Now, the drawing is out of my shower but my necks have improved. Just like using flashcards for a test, we start with little chunks first. I don’t think it would have worked as well if I would have put up an entire wall of Loomis anatomy drawings up, though that would make some interesting wallpaper?

There’s a lot to unpack here. How is what we are looking at online infusing into our work? How does what we experience/see in our life impact what we already know. But to stick to our topic, taking in information in a passive way, maybe an interesting method to come to our life studies in a more informed way and you can start it today.

Aggressive Approach

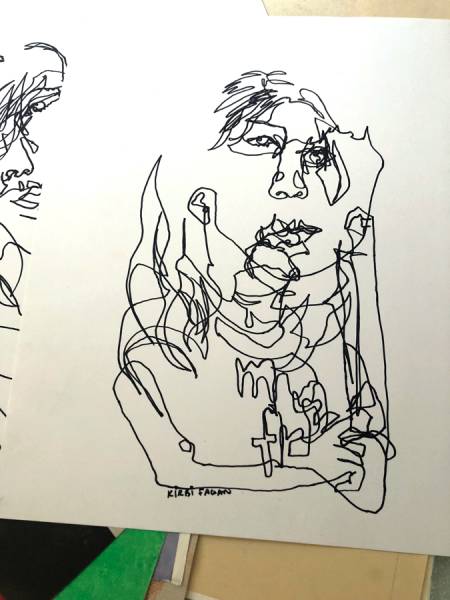

One day, frustrated with the figure, I sketched out, very basically, with no reference, a straight-standing figure, trying to get something like Loomis would have. When I was done, I checked my proportions to Loomis and corrected the drawing. Humbling. Sometimes we don’t know what we don’t know but this “test” pointed out all the parts I was struggling with.

I did this test every day (10 minutes on scrap paper) and after just a week, I was seeing changes. When I was set up in front of the model, I felt less stressed drawing from life. Every now and then, I test myself on different topics I may struggle with. The test points out the info I don’t know and gives me a chance, through doing to retain that info. Drawing is a very humbling thing, it can feel personal, especially when you are starting out. I encourage you to anticipate/prepare for those feelings to come up and give this a try. Your own sketchbook may be a perfect place to start.

If we can learn to anticipate the struggle, come to the drawing prepared and with a bit of grit, we can draw from life better. Eventually even from our imagination. Learning can be both passive and active. But we can’t expect to straddle our drawing horses without any background information and draw the model like a pro.

Happy drawing.

Kirbi

I feel like I arrived at a similar point in my work recently where I’m not consciously copying my ref or trying to nail down the “correct” details from drawing from life and honestly I feel like my drawing much more natural now which seems obvious but im a slow learner ( as you probably know). lol

I was telling a new painter that when looking at a subject to try seeing it in their minds eye. To me, that makes perfect sense.. until I realized that that comes from staring at your own work for thousands of hours. Your mind eventually just superimposes a personal filter unto everything you look at. Which is not the answer they were hoping for, eh.