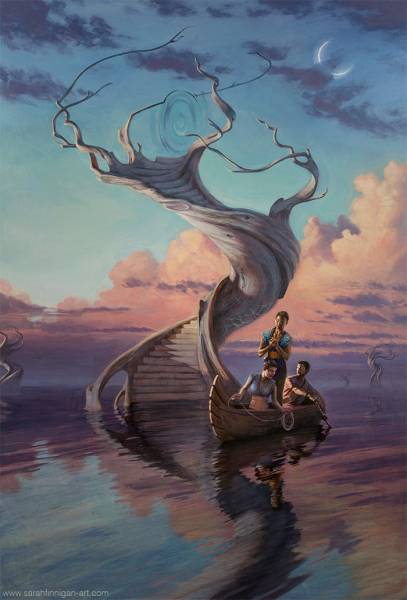

Survivor – 20″ x 30″ Acrylic on Wood

When I was young, my mom was constantly pointing out beautiful colors in the clouds, the varied shapes of different tree species, how a room’s decor made her feel. She has a passion for interior decorating and for nature photography, and I have her to thank for teaching me an appreciation of my surroundings, for training my eye early on color and composition.

As I got older, my dad and I would ride our bikes out past construction sites and down old logging trails or pipelines that extended well beyond our growing suburban area, just to see what we could find. We would search out old structures, like bridges that had been mostly washed away leaving leaning beams jutting from the river, or long-abandoned shacks in the woods.

Hindsight is 20/20, but it is amazing to me in retrospect that it took me so long to move toward landscapes in art. I began doing art in college as a replacement hobby when I quit video games. When I stopped, I didn’t miss gameplay at all, but sorely longed to walk through the worlds they transported me to. The first games I fell in love with, released when I was in elementary school, were Myst and its immediate sequel Riven. These games were experienced exclusively through your environment, piecing together what had happened from the imprints of characters that are no longer here. Exploring these abandoned spaces and gathering a story from what was left behind felt transformative.

I recently came across this wonderful video that, while telling a story, beautifully articulates the power of abandoned places, both real and fictional, and how communing with a physical space is most profound when we do it alone. I highly suggest it.

With places having a profound impact on me, why hadn’t I gravitated toward painting landscapes? Looking back, I had made a few assumptions without realizing it, and from them I’d built a box to live in.

The first came from André Félibien’s hierarchy of art*, which placed multiple-figure paintings as the most ambitious and highly esteemed of all art. I knew at the time that this notion was outdated and no artists are ‘better’ than others in such a graded way, but I also looked to my art heroes and it seemed to ring true. I wasn’t considering landscape art as an option at the time, but landscape was considered very lowly in this hierarchy. To add to that, I assumed all landscape artists were either doing plein-air work or making concept art, and that there was nothing more to it.

I also reasoned that the most desirable clients hired figurative work, and I desired those clients, so I must then do figurative work. I never looked critically at this assumption, such that when I eventually decided to pursue landscapes, part of that decision was mentally bidding farewell to the potential of working with those dream clients in the future. (I soon learned ‘what they say about assuming’ when a dream client, who’s door I had knocked on for years and gotten no response with a figure-filled portfolio, approached me a few months after I started in my new direction.)

It was easy to feel like I was working on subjects that mattered to me, since I love sci-fi/fantasy books, movies, and games…but I remember holding the work up as my own and feeling a bit like I was pretending to be someone else.

At my first IMC in 2017, I took a step forward and a step back. I had sketched a twisted tree with a staircase months before, but with no time to paint and no idea how to move it forward, it sat idle. I really liked the tree, so I pulled it back out for IMC and struggled to prepare various thumbnails that might bring in figures. What else could I do…focus exclusively on the really interesting part of the image and put the effort into making it better? No, it needed people. After it was completed, something about the painting felt right, felt me, but I couldn’t put my finger on it and failed to replicate that ‘something’ again and again for the next two years. The couple times I showed the painting to non-artists in my life, nobody asked about the tree-staircase or the distorted portal at the top, instead asking who the people were. In retrospect, I believe that is because they tonally didn’t fit…and when they asked, I didn’t have an answer for them.

The Way Between – painted at IMC 2017

Finally, the lightbulb moment came in 2019 when I sketched the thumbnail that would later be used for this small gouache painting. The ‘camera’ was placed over a rock path that sat a few inches under the surface of the water, making the thumbnail feel like a first-person view. Whatever had come to me for my IMC painting two years before, was here in this thumbnail! After two excited and frustrated days trying to figure out how to shoehorn a figure into the sketch without changing the tone or blocking anything I liked, the obvious solution finally dawned on me. As it was, it reminded me of those games I loved, and putting a figure into the composition took away that mystical feeling of being alone with a world to explore.

We might not all be particularly invested in landscapes, but we all carry assumptions we aren’t even aware of that hold us back. Perhaps that there are things we aren’t suited for, that we shouldn’t bother trying, or even that we aren’t allowed to explore. I hope this anecdotal post causes you to question what boxes you may have built around yourself. There were many times, in retrospect, it seems (if I believed such things) that the universe was trying to show me the way, and I danced around obvious answers to keep in step with rules that didn’t exist.

*From André Félibien’s apologia:

“In this art [of painting] there are different workers who apply themselves to different subjects; there is no doubt that to the degree to which they occupy themselves with the things that are the most difficult and the most noble, they separate themselves from what is lowest and most common, and ennoble themselves by more illustrious work. Therefore he who does landscapes perfectly is above someone who makes only [pictures of] fruits, flowers, or shells. He who paints living animals is more estimable than those who merely represent things that are dead and without movement; and as the human figure is the most perfect work of God on earth, it is certain that he who makes himself the imitator of God inpainting human figures, is much more excellent than all others….But the artist cannot rest here; while it is noble to depict the human figure, especially in groups (where the potential for representation of dramatic action becomes possible), the ambitious artist must represent ancient history and fable.”

Interesting article about your change in artistic direction Sarah. Since there are only a few examples here, I took a look at your website to see more. Your figure-less landscapes are incredible, and there is much more to them than mere landscapes!

Other artists have taken this path. For instance Maxfield Parrish ultimately grew weary of painting “girls on rocks”, and switched to pure landscapes later in his life. Maybe he was on to something, when he became older and wiser.

Thank you Joel! I hadn’t known that about Parrish…I’ve seen the landscape work, but assumed it was just something done between other pieces. I’ll have to take a deeper look at that!

I came across a video recently that stated something like landscape art isn’t interesting and one must paint figures to make it interesting. This felt like a too much of a simplification on how storytelling works. I feel that a lot can be said, or wonder about without the presence of a figure.

This article and the video you shared touches on what I have been thinking lately and the direction I have been wanting to take with my work. Thanks so much for sharing this!!

(by the way, Edith Finch game was incredibly inspirational to me. I LOVED it and if you have a chance, I recommend doing a play through. I really hope more and more games come out with this type of format)

To me, figures come with so much baggage. There’s no such thing as a blank slate…the viewer brings assumptions, interpretations, stereotypes, etc into the painting with them. That could be a good thing, but it was always frustrating to me.

I bought Edith Finch after watching this video a few months ago, but between a lack of time and a fear of losing control of my time, I’ve not started it. I worry it is a slipper slope…there was a good reason I gave up gaming years ago. If you’re looking for more, maybe less depressing too…Riven has held up wonderfully and is very inexpensive on mobile.

This article came at the right time for me and thank you for writing about this!! Lately, I’ve been telling myself that incorporating figurative work is the only way I’ll get the jobs I want, so it’s refreshing to hear someone else has felt the same and it didn’t prove to be true. I’ve always wondered if it’s because I don’t feel confident in drawing the figure that I avoid incorporating it into my drawings. This is true to a certain extent and I’ll go through bursts of making myself work on that skill, but maybe the fact that I’ve never naturally gravitated toward cultivating it is something to listen to about what I truly love and how I think!

Blimey, this hit me in the gut! Thanks for writing this, it’s given me lots of food for thought 🙂