So I’ve already pulled two columns here from my trip to the Manet/Degas exhibit at the Met: First we had one in the Turning Points series about how controversial Manet really was, especially his painting Olympia. Next we went a little deeper and talked about Manet’s paintings and how they play with the Male vs Female Gaze and that that means in Art. Now I’m going to focus on the biggest takeaway I got from this incredible show — a reminder to always think about Artists not as isolated pieces of Art or even a body of work made in a vacuum, but a dynamic trajectory bouncing off other artists, politics, social scenes, and interacting with other Artists and all of Art History up to that point.

This exhibit was set up to really show how much interaction Manet and Degas had while they were working artists, and how that affected not only their work, but the entire Impressionist movement. These Artists were not only aware of each other’s work, as many of us know from our Art History study, but they were friends, they painted the same things on the same days, they made works that copied or spoke directly to the other, and you could easily make the case that we might not have the respect for Manet we do if not for Degas’s work to preserve and promote Manet’s work after his death.

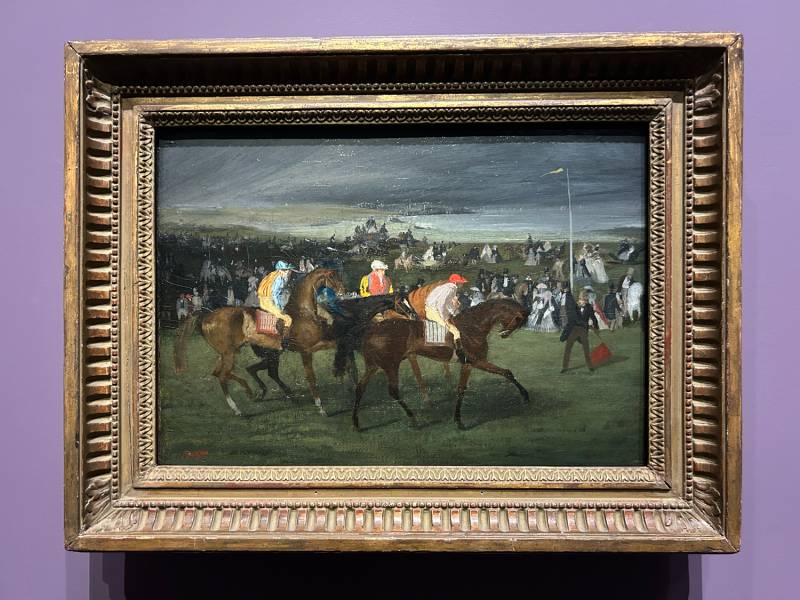

A great example are Manet and Degas’s paintings at the Bois de Boulogne Racetrack outside Paris:

It isn’t rare for two painters of the same time in the same city to paint the same location or subject, but it is very enlightening to know that Manet only went to the racetrack at all because of Degas, that they went together, sketched together, and may have included each other as cameos in each of their paintings that came from those sketches. This reminds me of all the paintings I’ve seen spring up at the Illustration Master Class over the years, where everyone is modeling for each other’s reference. Does it change the painting as a work? Not necessarily, but the context deepens our understanding and reminds us that no artist works uninfluenced.

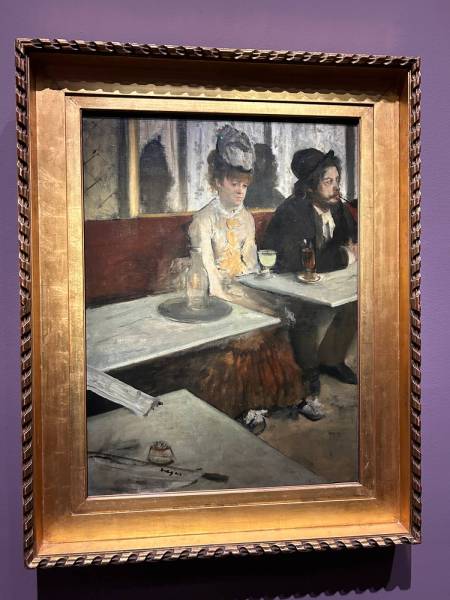

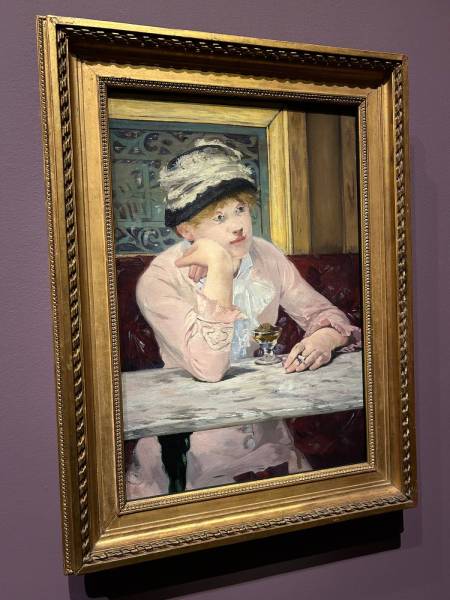

Here’s an even more interesting dialogue between works:

After Degas painted his famous Absinthe Drinker, Manet hired the same model, had her wear the same clothes, in the same bar (but not the same drink, this time it was plum brandy) in order to work on his version. I think Artists working in the same communities/schools do this often, and it’s fascinating to see these two masters working on such similar scenes. The emotion is so different between the two, for all that the details are identical.

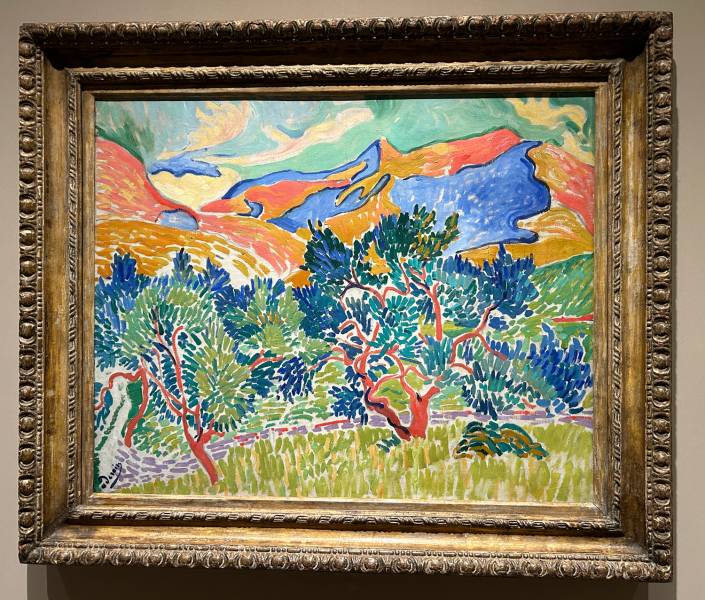

This dialogue happens often between artists, and it was also highlighted in another exhibit currently up at the Met on Matisse, Derain, and the origins of Fauvism. You may be familiar with Matisse’s work and Derain’s work, but would you ever realize — if a curator didn’t pose a show to point it out — that these two canvases were painted together, at the same time, of the same scene, while Matisse and Derain were traveling together?

It brings so much more to these works to know the context — that these two Artists were friends, and that they were standing together in a field trying to work out how to push the boundaries of the Impressionists who came before, and give birth to a new Art movement altogether. Obviously they reacted to each other’s works, were discussing what and how they saw, inspired each other to be more innovative. Knowing this context brings so much more to the works, especially for other Artists. Remember that Manet, Degas, Matisse, and Derain were not lone mavericks out making work on their own — they were supported and encouraged, challenged and inspired, by their community of Artists. And even when it’s not spelled out by curators in exhibits such as this, remember to assume there is context to works you see and Artists you admire. Remember to take as much of the context as you can find into account, and the context around works you make as well.

I’ll leave you with a last image from the Manet/Degas exhibit that I found incredibly charming: Manet’s Ham

Degas held this painting in his personal collection. It was a trade of Manet’s, offered in exchange for a small painting and some pastels. Is it a masterwork? Not really. It’s only important to us because Manet painted it and he’s considered a Master. And this traded painting only survives because it was traded to and loved by another artist. And after Manet died, it was Degas and Monet who saved his works, kept his notes, and convinced the French government to buy Olympia as a national treasure. Knowing this context makes all these paintings the richer for us.

Recent Comments