There are as many ways to approach crafting a graphic novel as there are creators trying to do so. But without being overly equivocal, there are better ways to do it than others, and this is but one way to attack a project. It seemed fitting to use my current collaborative project with Ethan Hawke, the graphic novel INDEH as the subject. Ours was a particularly wild ride getting this to the production stage and it should hopefully provide a window into how to navigate and deal with the ups and downs of the process.

I was initially contacted by Ethan through our respective agents to take this project on after he’d read my work on Kurt Busiek’s Conan: Born on the Battlefield. He loved the collection and felt like perhaps for the first time he’d seen the way to visualize his long simmering and massive script, INDEH. We live in a time where comics are being used as a means to a film, and this is in my opinion, a devil’s handshake. The opportunity both bestows a larger sense of attention to a medium that has suffered terribly under the insane stewardship of the comics industry for so many generations, but also robbing it of its legitimacy as a valid stand alone medium unto itself. So my first reaction of Ethan’s interest was one of caution. I would never and could never do a project as long and involved as a graphic novel solely to make it into a movie. That to me is a loathsome practice. But it turns out he was entirely devoted to the notion of this as a book unto itself. If there was to be something later, then we’d worry about that later. Right now we had a book to discover.

We first got together in a café near his former home on the west side of the Chelsea area in Manhattan, and despite every reticence I may have had about meeting a famous movie star, we got on like a house on fire. We had a similar background both growing up in Texas and being of the same age, but beyond that we just simply clicked. I cannot insist enough how essential this basic foundation is when working with a creative partner on any project, much less one as long and involved as a graphic novel of this scale. Building something like this is a lot of work, demands long hours and requires a deep creative intimacy based on trust and mutual respect. Without that, you are doomed right out of the gate. No matter how much you think you may get out of a chance to work with a famous person, or on a high profile project of any kind, it will all turn to dross if the relationship lacks this most basic element. The chemistry just has to be there. And the story had to demand to be told in this form.

One of my triggers for this is when reading a proposal, to see if it sparks visuals in my head while reading it. Not all of them do, and those that don’t are best left behind. If you can’t see the book, as an artist, in your own mind then there’s no way you’re going to be able to visualize it on the page in a successful way later. Indeh exploded in my head after the first few pages so this was an easy one. I adored it beyond words. I was so exhausted by the process of the The Lost Boy at this time, I never expected to be so taken and excited by another giant book, but once I read this I had no choice really. Whether we’d ever find a publisher or not didn’t matter. This story needed to be told and I felt honored beyond words for the opportunity to tell it with Ethan.

Once we agreed that if we were to really take this on, it would have to be entirely about making the best book we could make. Any talk of film later or whatever had to be taken off the table so as not to pollute the process. Much to the contrary of many screenwriters and movie producers, comics and graphic novels are not storyboards for films. At least the ones that work aren’t. Ethan, I think, was especially glad to agree to this and we were off.

The first thing to do was to read, and then reread the screenplay he’d written and find a way to pull a fully realized graphic novel out of it. And it was a beast of a script- clocking in at around 340 pages- which is crazy long for a screenplay. The big challenge though was what to cut out- so much of it was truly great and alluring, it was clear early on it was going to be brutal exercise in pruning than one of building. The initial problem with most biographies, (and Geronimo being at the center of this tale made this essentially a biography), is that the arc of a human life isn’t really well suited for dramatic storytelling. Bios become chronicles of events or at best, a catlaogue with an overlay of some kind of theme, (Charles Foster Kane’s chasing after the one thing he could never buy as symbolized by his childhood sled “Rosebud”, for example). Neither make for an especially compelling read unless the reader is already predisposed to being interested in the subject matter. We wanted to grab people who thought they knew all they needed to know about Geronimo and the Apaches, and we also wanted to turn the heads of those who would never think to read a book, especially a graphic novel, about them. That meant finding the story to tell within the piles of dense and incredibly alluring interviews and anecdotes contained within the script. And that took almost a full year of work.

Graphic novels are not comics, nor is a collection of comics a graphic novel. Collecting a series of single issues into a 200 page book is not the same as writing and drawing a full fledged narrative meant as a 200 page novel, told graphically. The structure and arcs are entirely different and each have their own value, but are not the same at all. I conceive of and write long form comics narratives and now publish them through book companies and thus I am for the first time in my career, a graphic novelist. I’ll delve into the newly changing landscape of periodical comics publishing and the book world’s new love for the medium in later articles, but for now… back to Indeh.

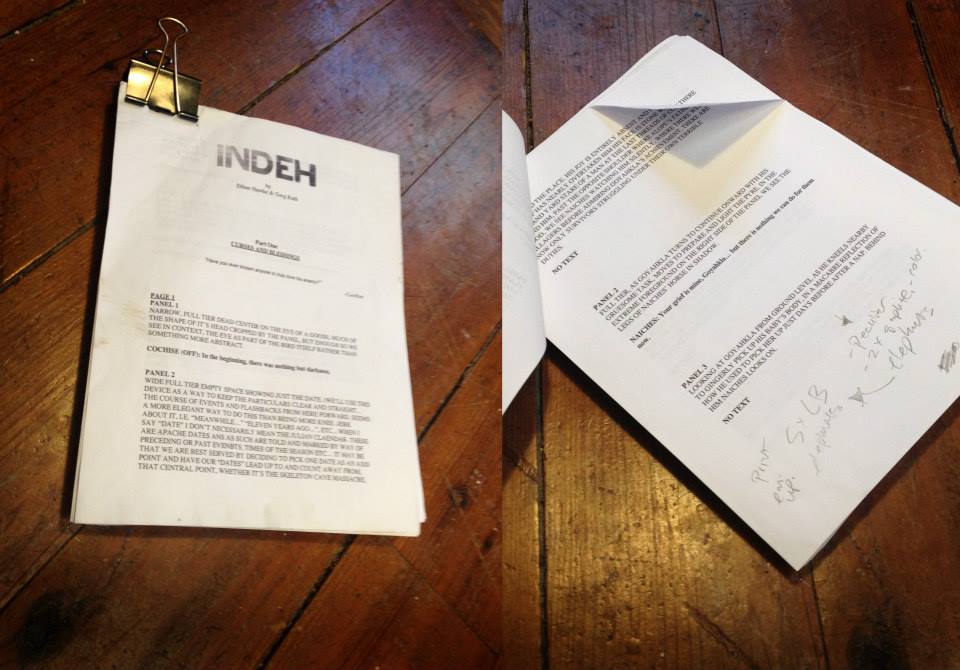

Despite being a published writer in his own regard, Ethan was new to comics. But despite the myriad differences between film and graphic novels, there are enough commonalities that helped us fast-track the learning curve and get right into it. So for that year we each traveled back and forth to our homes and offices to meet and sit on the floor with reams of paper pulling together our favorite bits, casting aside others and honing this might beast of a script down into a cogent and trim narrative. I had not written a full detailed script for myself before but in this case it seemed essential, and being the comics guy of the team, the first draft of that script fell to my shoulders. No all of us who draw comics can write, but we should all of us, train ourselves in how to tell a story well at the very least. Even if you’re simply executing the details of a script- as was mostly the case when I did Conan with Kurt, how you position the images and the panels requires a fundamental understanding of stories and narratives. You don’t have to go to school for it- I never did- but you do need to study it whether in comics or even in film. Read or watch what you love, study why it works, and read or see what you hate and study why it doesn’t. Sometimes the bad stuff can be more educational than the good.

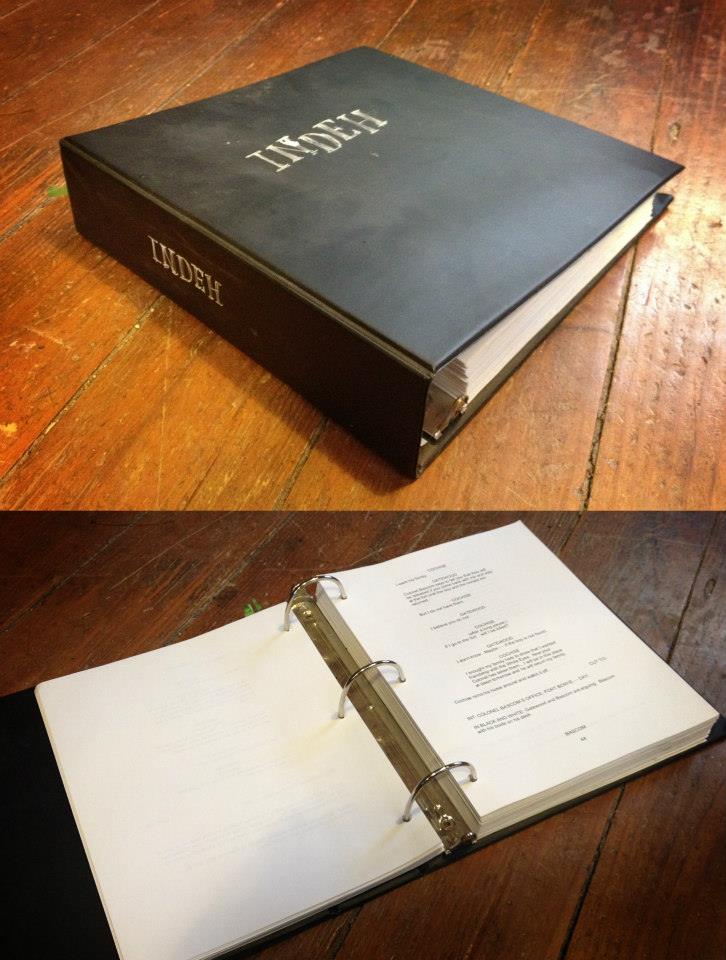

So. Once we figured out our themes, and our structure I set about using all our collected notes, Ethan’s research and transcribed interviews, and began working a proper fully detailed panel by panel comics script for Indeh. My first and last love in this area is Alan Moore, and I’ve studied most of his scripts for his books for years and tend towards this form in my own: detailed panel descriptions attended to by movie script style dialogue, page after page. It’s a simple and basic approach to this kind of thing and was such a successful exercise I now employ it for every project I take on. This isn’t to say once scripted, I as the artist is now fully married to the script in every detail. As with film, the script is not the book, and a lot more comes into play when you start translating the pages into pictures. New ideas arise, previous ones thought to be brilliant turn out to be clunky and unworkable. So the script becomes the map for the journey rather than the journey itself. But what it does do is bring about a greater freedom to let yourself more freely explore the story visually because, like a map, it will keep you from getting lost. So we parried back and forth, adding this and removing that. Rewriting remotely in our respective homes, then chatting on the phone and coming together when our schedules allowed to slowly and seriously build our story. In the end we both crafted a roughly 200 pages graphic novel script. I can say that despite how overlong this stage of the process felt, it was at times and often, the most fun I have ever had on a project before.

This was all simultaneous with ramping up and scheduling pitch meetings with publishers, and the early stages of crafting the look of the book through its characters and design. I’ll spend the next entry laying out that process and talking about the dos and don’ts that come with setting and making pitch meetings, story kits and what is best to think about when it comes to picking the right publishing house for a project like this. I’m heading out to New Mexico this week to meet Ethan and explore the area and meet with some folk out there and will include some of that research in the forthcoming articles, as well as interspersing other posts about the medium of comics in general, children’s picture books and the ins and outs of making a business out of being a freelance creator of such things. I hope you’ll get something out of it.

Feel free to ask any question that comes to you and I’ll endeavor to provide some kind of cogent answer as best as I can!

I was looking forward to this Greg and you don't disappoint. Really interesting read. I'm curious to see how the process progresses. How do you eat during all of this?

Writing and creating panels for graphic novels is one of the hardest things I'm attempting to do and have ever attempted to do. I totally agree with your insights but was curious about how you deal with the cutting and editing process which lead me to thinking there had to be a better way to bridge the gap between not just the artist and the writer, but that creative team with the medium itself. It's almost as if you both need to create simultaneously FOR the medium…but do you think that is possible at all, or is it necessary to split the task into writing and art making phases?

As a person with a graphic novel story and images in my head that I'm trying solidify and create, I am very interested in this project. Thanks for the insight and I look forward to more.

Welcome to the crew Greg!

your site very inspiration and informatif

The trick is going to be keeping my usual habit of over blathering to a concise minimum. Thanks for coming aboard the crazy train

It is a supremely difficult medium to do correctly, and uber time consuming. You have have no choice but to do stories this way, or perhaps simply bee insane. Ethan and I have an unusual simpatico in collaborating on this book, and that kind of process is keeping this as fluid and organic as anything I have ever done before. I think being able to write and draw well, both whole disciplines on their own, is the hardest barrier to doing this well together. I did The Lost Boy without a script and let the story emerge by the act of drawing it. I don't think I would ever do that again, though. Being able to organize plot and character through a script, even you are your own artists for the book, is really essential. It's the fence that provides freedom. With a script and planning you are then freer to run wild in its interpretation without fear of getting lost in the weeds. It's hard as an artist to avoid getting caught up in the minutia of an individual drawing or panel at the expense of the story you are required to tell.

Thanks! It's great to be here, and in such fine company. Feel free to ask any question that comes to you, and I will do my level best to provide a worthy answer.